Difference between revisions of "Ancient Greek Comedy" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Robot: Category fix) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (53 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Copyedited}}{{submitted}}{{images OK}}{{approved}} | |

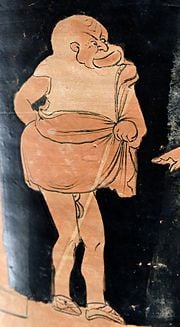

| + | [[Image:Theatre slave Louvre CA7249.jpg|thumb|right|180px|[[Slave]] wearing the short tunic, phlyax [[actor]]. Detail, side A from a Silician red-figured calyx-krater, ca. 350 B.C.E.–340 B.C.E.]] | ||

| + | [[Comedy]], together with [[tragedy]] was one of two principal [[drama|dramatic]] forms of [[Theater of Ancient Greece|ancient Greek theater]]. Athenian comedy is conventionally divided into three periods: ''Old Comedy'', ''Middle Comedy'', and ''New Comedy''. Old Comedy survives today largely in the form of the eleven surviving plays of [[Aristophanes]], while New Comedy is known primarily from the substantial papyrus fragments of [[Menander]]. Middle Comedy is largely lost, i.e. preserved only in relatively short fragments in authors such as [[Athenaeus of Naucratis]]. | ||

| − | + | The Old Comedy, dating from the establishment of [[democracy]] by Kleisthenes, about 510 B.C.E., arose from the obscene jests of [[Dionysus|Dionysian]] revelers, composed of virulent abuse and personal vilification. The satire and abuse were directed against some object of popular dislike. The comedy used the techiques of [[tragedy]], its choral dances, its masked actors, its meters, its scenery and stage mechanism, and above all the elegance of the [[Attic Greek|Attic language]], but used for the purpose of satire and ridicule. Middle Comedy omitted the chorus, and transferred the ridicule from a single personage to human foibles in general. The transition in comedy from old to middle represented a major step forward in the artistic nature of comedic drama, from one of pure ridicule to addressing the larger question of the foibles of human nature. | |

| − | + | At [[Athens]] the comedies became an official part of the festival celebration in 486 B.C.E., and prizes were offered for the best productions. As with the tragedians, few works still remain of the great comedic writers. Of the works of earlier writers, only some plays by [[Aristophanes]] exist. These plays represent an important advance in comic presentation. He poked fun at everyone and every institution. Aristophanes is the ancestor for much of later comic theater. For boldness of fantasy, for merciless insult, for unqualified indecency, and for outrageous and free political criticism, there is nothing to compare to the comedies of Aristophanes. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | During the fourth century B.C.E., there developed what was called the [[New Comedy]]. [[Menander]] is considered the best of its writers. Nothing remains from his competitors, however, so it is difficult to make comparisons. The plays of Menander, of which only the Dyscolus ([[Misanthrope]]) now exists, did not deal with the great public themes about which [[Aristophanes]] wrote. He concentrated instead on fictitious characters from everyday life: stern fathers, young lovers, intriguing slaves, and others. In spite of his narrower focus, the plays of Menander influenced later generations. They were freely adapted by the [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] poets [[Plautus]] and [[Terence]] in the third and second centuries B.C.E.. The comedies of the [[France|French]] playwright [[Molière]] are reminiscent of those by Menander. | ||

| − | + | ==Origins== | |

| + | [[Image:NAMA Masque esclave.jpg|thumb|left|220px|[[Ancient Greek Theatre|Theatre]] mask of a ''First Slave'' in [[Greek comedy]], second century B.C.E., [[National Archaeological Museum of Athens]]]] | ||

| + | There is little exact information regarding the origin and early development of ancient Greek comedy. According to [[Aristotle]], writing a century and a half later, it first took shape in [[Megara]] and [[Sicyon]]; [[Susarion]], the earliest Athenian comic poet, is himself supposed to have come from Megara. Aristotle also connects the origin of Comedy with popular phallic processions, and claims that it received official recognition (and thus state support) in Athens ''somewhat later'' than tragedy did. The Suda, supplemented by some inscriptional evidence, suggests that the earliest dramatic competitions in Athens took place at the [[City Dionysia]] festival in the early 480s B.C.E., and that a second competition was added at the [[Lenaea]] festival around 450. But comedies of some sort written by [[Epicharmus]] were performed already in the 490s in the Greek city of [[Syracuse, Italy|Syracuse]] in Sicily, and the origins of the genre cannot in fact be determined with any precision. The name itself apparently comes from the Greek words [[komos]], which means ''reveling band'', and the verb ''aeido'', ''to sing''. | ||

| − | + | Comedies were performed in Athens in formal competitions at two major festivals in honor of [[Dionysus]], the god of wine and revelry, now associated with theater. Each festival seems to have featured five comic poets staging a single play apiece, although it is possible that programs were reduced to three poets for a period due to the financial pressures of the [[Peloponnesian War]]. Poets applied to the [[archon]] in charge of the relevant festival for the right to participate in it. If chosen, they were awarded a [[choregos]], i.e. a wealthy man who funded the performance as a form of taxation. | |

| − | + | In ancient [[Greece]], comedy seems to have originated in bawdy and [[ribald]] songs or recitations apropos of fertility festivals or gatherings, or also in making fun at other people or stereotypes. [[Aristotle]], in his Poetics, states that comedy originated in Phallic songs and the light treatment of the otherwise base and ugly. He also adds that the origins of comedy are obscure because it was not treated seriously from its inception.<ref>Aristotle, [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Aristot.+Poet.+1449a Poetics], lines beginning at 1449a. Retrieved August 20, 2008.</ref> | |

| − | == | + | ==Periods of Ancient Greek Comedy== |

| + | The [[Alexandrine grammarians]] seem to have been the first to divide Greek comedy into what became the canonical three periods:<ref name="Mastromarco94">Mastromarco (1994), 12.</ref> Old Comedy ''(archàia)'', Middle Comedy ''(mese)'' and New Comedy ''(nea)''. These divisions appear to be largely arbitrary, and ancient comedy almost certainly developed constantly over the years. | ||

| − | + | ===Old Comedy ''(archàia)''=== | |

| − | ===Old Comedy=== | + | The earliest Athenian comedy, from the 480s to 440s B.C.E., is almost entirely lost. |

| + | |||

| + | In order to impress the refined and cultured community of [[Athens]] in the age of [[Pericles]], the dramatists of the Old Comedy borrowed all its most attractive features from [[tragedy]]: choral dances, masked actors, poetic [[meter|meters]], scenery and stage mechanisms, and the dramatic form of [[Attic Greek]]. Thus comedy became a recognized branch of the drama, presenting brilliant dialogue and poetic beauty in the choral parts comparable to tragedy plays of the same period. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Aristophanes=== | ||

| + | The most important dramatist of the Old Comedy was [[Aristophanes]]. His works define the legacy of Old Comedy, with their pungent political satire and abundance of sexual and scatological innuendo. Aristophanes lampooned the most important personalities and institutions of his day, as can be seen in his buffoonish portrayal of [[Socrates]] in ''[[The Clouds]]'', and in his anti-military farce ''[[Lysistrata]]''. In ''[[The Birds (play)|The Birds]]'' he held up Athenian democracy to ridicule. Only 11 of his plays have survived. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Lysistrata==== | ||

| + | Led by the title character, Lysistrata, the story's female characters barricade the public funds building and withhold sex from their husbands to end the [[Peloponnesian War]] and secure [[peace]]. In doing so, Lysistrata engages the support of women from [[Sparta]], [[Boeotia]], and [[Corinth]]. All of the other women are first against Lysistrata's suggestion to withhold sex. Finally, they agree to swearing an oath of allegiance by drinking wine from a phallic shaped flask, as the traditional implement (an upturned shield) would have been a symbol of actions opposed to the aims of the women. This action is ironic and therefore comical, because Greek men believed women had no self-restraint, a lack displayed in their alleged fondness for wine as well as for sex. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====The Frogs==== | ||

| + | ''The Frogs'' had a more serious tone than some of Aristophanes other comedies. However, ''The Frogs'' is unique in its structure, because it combines two forms of comic motifs, a journey motif and a contest motif or ''[[agon]]'' motif, with each motif being given equal weight in the play. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Influence=== | ||

| + | The Old Comedy subsequently influenced later European writers such as [[Rabelais]], [[Cervantes]], [[Jonathan Swift|Swift]], and [[Voltaire]]. In particular, they copied the technique of disguising a political attack as buffoonery. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The legacy of Old Comedy can be seen in contemporary times in political satires such as ''[[Dr. Strangelove]]'' and in the televised buffoonery of [[Monty Python]] and ''[[Saturday Night Live]]''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Middle Comedy ''(mese)''=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The line between Old and Middle Comedy is not very clearly marked, [[Aristophanes]] and others of the latest writers of the Old Comedy becoming the earliest writers of the Middle Comedy. The Middle Comedy was an offshoot of the Old Comedy, but differed from it in three essential particulars: Middle Comedy had no [[chorus]], public characters were not impersonated or personified on the stage, and the objects of ridicule were general rather than personal, literary rather than political. Where Old Comedy was caricature and lampoon, Middle Comedy was criticism and review. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The period of the Middle Comedy extended from the close of the [[Peloponnesian War]] to the enthrallment of [[Athens]] by [[Philip of Macedon]]; that is, from the closing years of the [[5th Century B.C.E.|fifth century B.C.E.]] to nearly the middle of the [[fourth century B.C.E.]]. It was extremely prolific in plays, but not especially so in genius. The favorite themes were the literary and social peculiarities of the day, which, together with the prominent systems of [[philosophy]], were treated with light and not ill-natured ridicule. The Middle Comedy freely parodied the grandest tragedies of [[Aeschylus]] and [[Sophocles]], the noblest passages of [[Homer]], and the most beautiful lyrics of [[Pindar]] and [[Simonides]]. Subjects taken directly from ancient mythology were treated in the same way. In dealing with society, classes rather than individuals were attacked, as courtesans, parasites, revelers, and especially the self-conceited cook, who, with his parade of culinary science, was always a favorite target for the shafts of middle comedy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===New Comedy ''(nea)''=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Figurine actor BM TerrD226.jpg|thumb|Molded terracotta figurine of an actor wearing the mask of a bald-headed white man, from the New Comedy, second century B.C.E., from [[Canino]], Italy.]] | ||

| + | The new comedy lasted throughout the reign of the [[Macedonian]] rulers, ending about 260 B.C.E. | ||

| − | + | Very little of the text of the New Comedy has survived. A few Greek fragments have come down to us. During the twentieth century the complete text of ''[[Dyskolos]]'', a play by [[Menander]], the leading writer of New Comedy, was rediscovered. It is the only example of New Comedy to have survived in its entirety. A few long fragments by Menander have survived as well from such plays as The Arbitraton, [[The Girl from Samos]], The Shorn Girl, and The Hero). Much of our information about the New Comedy is derived from the [[Latin]] adaptations by [[Plautus]] and [[Terence]]. | |

| − | + | For the first time love became a principal element in the drama. The New Comedy relied on [[stock character]]s such as the [[senex iratus]], or "angry old man," the domineering parent who is all too often led into the vices and follies for which he has reproved his son, and the [[Miles Gloriosus|bragging soldier]] or mercenary soldier newly returned from war with a noisy tongue, a full purse and an empty head. With these exceptions, the characters were very much the same as in the middle comedy. The new comedy represented Athenian society and the social morality of the period; but it made no attempt to improve it, presenting only in attractive colors. | |

| − | + | The New Comedy influenced much of Western European literature, in particular the comic drama of [[William Shakespeare|Shakespeare]] and [[Ben Jonson]], [[William Congreve (playwright)|Congreve]] and [[William Wycherley|Wycherley]].<ref>Alfred Bates (ed.), ''The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization'', vol. 1. (London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906), 30-31.</ref> | |

| − | + | Much of contemporary romantic and situational comedy descends from the New Comedy sensibility, in particular generational comedies such as ''[[All in the Family]]'' and ''[[Meet the Parents]]''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==See also== | |

| + | *[[Agon]] at the [[Dionysia]] (mixed audiences) and [[Lenaia]] (local Athens audience only) | ||

| + | *[[Phallic processions]] | ||

| + | *[[Theatre of Dionysus]] | ||

| + | *[[Cult of Dionysus]] | ||

| + | ==List of Comic Dramatists== | ||

| + | Some dramatists overlap into more than one period. | ||

| + | ===Old Comedy=== | ||

| + | *[[Susarion]] of [[Megara]] (~580 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *[[Epicharmus of Kos]] (~540-450 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *[[Cratinus]] (~520-420 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *[[Chionides]] 486 B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Magnes (comic poet)|Magnes]] 472 B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Eunicus]] Fifth c. BC | ||

| + | *[[Eupolis]] (~446-411 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *[[Hegemon of Thasos]] Fifth century B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Telecleides]] Fifth century B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Pherecrates]] Fifth century B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Crates (comic poet)]] ca.450 century B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Hermippus]] 435 B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Phrynichus (comic poet)|Phrynichus]] (~429 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *Cantharus 422 B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Strattis]] (~412-390 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *Cephisodorus 402 B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Plato (comic poet)]] late Fifth century B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Nicophon]] Fifth century B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Nicochares]] (d.~345 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *[[Callias Schoenion]] | ||

| + | *[[Sannyrion]] | ||

| + | *[[Diocles of Phlius]] | ||

| + | *'''[[Aristophanes]]''' (~456–386 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *His sons Araros, Philippus, and Nicostratus were also comic poets. | ||

| + | *[[Antiphanes]] (~408-334 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Middle Comedy=== | ||

| + | *[[Eubulus (poet)|Eubulus]] early Fourth century B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Epicrates of Ambracia]] Fourth century B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Anaxandrides]] Fourth century B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Alexis]] (~375 B.C.E. - 275 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *'''[[Menander]]''' (~342–291 B.C.E.) | ||

===New Comedy=== | ===New Comedy=== | ||

| + | *Philippides | ||

| + | *[[Philemon (poet)|Philemon]] of [[Soli, Cilicia|Soli]] or [[Syracuse, Sicily|Syracuse]] (~362–262 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *[[Apollodorus of Carystus]] (~300-260 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *[[Diphilus]] of [[Sinope]] (~340-290 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *[[Machon]] of Corinth/Alexandria Third century B.C.E. | ||

| + | *[[Poseidippus of Cassandreia]] (~316–250 B.C.E.) | ||

| + | *Laines or Laenes 185 B.C.E. | ||

| + | *Philemon 183 B.C.E. | ||

| + | *Chairion or Chaerion 154 B.C.E. | ||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | {{Reflist}} | ||

| − | ==References== | + | ==References== |

| − | * Aristotle | + | * Aristotle. [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Aristot.+Poet.+1449a ''Poetics'', lines beginning at 1449a] Retrieved August 18, 2008. |

| − | *''The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization'', volume 1 | + | * Bates, Alfred. ''The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization'', volume 1. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. OCLC 3711069 |

| − | * P.W. | + | * Buckham, P.W. ''Theatre of the Greeks''. Cambridge, Eng.: Printed by J. Smith, 1827. OCLC 4234970 |

| − | * | + | * Cornford, F. M. ''The Origin of Attic Comedy''. 1934. OCLC 431202 |

| − | * | + | *[[Giuseppe Mastromarco|Mastromarco, Giuseppe]]. 1994. ''Introduzione a Aristofane''. Sesta edizione: Roma-Bari 2004. ISBN 8842044482 |

| + | *Riu, Xavier. [http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/bmcr/2000/2000-06-13.html ''Dionysism and Comedy''] 1999. Retrieved August 18, 2008. | ||

| + | *[http://www.researchislife.net/oldcomedy Old Comedy] Retrieved August 18, 2008. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved July 26, 2023. | ||

| + | |||

*[http://www.theatrehistory.com/ancient/bates001.html An article on the origin of comedy] | *[http://www.theatrehistory.com/ancient/bates001.html An article on the origin of comedy] | ||

| − | *[http:// | + | *[http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/522/1/heathm17.pdf "Aristotle on Comedy"] by Malcolm Heath, University of Leeds. |

| − | *[http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/inourtime/inourtime_20060713.shtml BBC Radio 4 "In Our Time" | + | *[http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/inourtime/inourtime_20060713.shtml Comedy in Ancient Greek Theatre ] BBC Radio 4 "In Our Time" program on ancient Greek Comedy, Thursday 13 July 2006. |

| + | |||

[[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | ||

| − | {{credit1| | + | {{credit1|Ancient_Greek_Comedy|231054657|Lysistrata|225589177|The_Frogs|218706093|Comedy|230825120|Ancient_Greek_literature|232648704}} |

Latest revision as of 19:24, 26 July 2023

Comedy, together with tragedy was one of two principal dramatic forms of ancient Greek theater. Athenian comedy is conventionally divided into three periods: Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy. Old Comedy survives today largely in the form of the eleven surviving plays of Aristophanes, while New Comedy is known primarily from the substantial papyrus fragments of Menander. Middle Comedy is largely lost, i.e. preserved only in relatively short fragments in authors such as Athenaeus of Naucratis.

The Old Comedy, dating from the establishment of democracy by Kleisthenes, about 510 B.C.E., arose from the obscene jests of Dionysian revelers, composed of virulent abuse and personal vilification. The satire and abuse were directed against some object of popular dislike. The comedy used the techiques of tragedy, its choral dances, its masked actors, its meters, its scenery and stage mechanism, and above all the elegance of the Attic language, but used for the purpose of satire and ridicule. Middle Comedy omitted the chorus, and transferred the ridicule from a single personage to human foibles in general. The transition in comedy from old to middle represented a major step forward in the artistic nature of comedic drama, from one of pure ridicule to addressing the larger question of the foibles of human nature.

At Athens the comedies became an official part of the festival celebration in 486 B.C.E., and prizes were offered for the best productions. As with the tragedians, few works still remain of the great comedic writers. Of the works of earlier writers, only some plays by Aristophanes exist. These plays represent an important advance in comic presentation. He poked fun at everyone and every institution. Aristophanes is the ancestor for much of later comic theater. For boldness of fantasy, for merciless insult, for unqualified indecency, and for outrageous and free political criticism, there is nothing to compare to the comedies of Aristophanes.

During the fourth century B.C.E., there developed what was called the New Comedy. Menander is considered the best of its writers. Nothing remains from his competitors, however, so it is difficult to make comparisons. The plays of Menander, of which only the Dyscolus (Misanthrope) now exists, did not deal with the great public themes about which Aristophanes wrote. He concentrated instead on fictitious characters from everyday life: stern fathers, young lovers, intriguing slaves, and others. In spite of his narrower focus, the plays of Menander influenced later generations. They were freely adapted by the Roman poets Plautus and Terence in the third and second centuries B.C.E. The comedies of the French playwright Molière are reminiscent of those by Menander.

Origins

There is little exact information regarding the origin and early development of ancient Greek comedy. According to Aristotle, writing a century and a half later, it first took shape in Megara and Sicyon; Susarion, the earliest Athenian comic poet, is himself supposed to have come from Megara. Aristotle also connects the origin of Comedy with popular phallic processions, and claims that it received official recognition (and thus state support) in Athens somewhat later than tragedy did. The Suda, supplemented by some inscriptional evidence, suggests that the earliest dramatic competitions in Athens took place at the City Dionysia festival in the early 480s B.C.E., and that a second competition was added at the Lenaea festival around 450. But comedies of some sort written by Epicharmus were performed already in the 490s in the Greek city of Syracuse in Sicily, and the origins of the genre cannot in fact be determined with any precision. The name itself apparently comes from the Greek words komos, which means reveling band, and the verb aeido, to sing.

Comedies were performed in Athens in formal competitions at two major festivals in honor of Dionysus, the god of wine and revelry, now associated with theater. Each festival seems to have featured five comic poets staging a single play apiece, although it is possible that programs were reduced to three poets for a period due to the financial pressures of the Peloponnesian War. Poets applied to the archon in charge of the relevant festival for the right to participate in it. If chosen, they were awarded a choregos, i.e. a wealthy man who funded the performance as a form of taxation.

In ancient Greece, comedy seems to have originated in bawdy and ribald songs or recitations apropos of fertility festivals or gatherings, or also in making fun at other people or stereotypes. Aristotle, in his Poetics, states that comedy originated in Phallic songs and the light treatment of the otherwise base and ugly. He also adds that the origins of comedy are obscure because it was not treated seriously from its inception.[1]

Periods of Ancient Greek Comedy

The Alexandrine grammarians seem to have been the first to divide Greek comedy into what became the canonical three periods:[2] Old Comedy (archàia), Middle Comedy (mese) and New Comedy (nea). These divisions appear to be largely arbitrary, and ancient comedy almost certainly developed constantly over the years.

Old Comedy (archàia)

The earliest Athenian comedy, from the 480s to 440s B.C.E., is almost entirely lost.

In order to impress the refined and cultured community of Athens in the age of Pericles, the dramatists of the Old Comedy borrowed all its most attractive features from tragedy: choral dances, masked actors, poetic meters, scenery and stage mechanisms, and the dramatic form of Attic Greek. Thus comedy became a recognized branch of the drama, presenting brilliant dialogue and poetic beauty in the choral parts comparable to tragedy plays of the same period.

Aristophanes

The most important dramatist of the Old Comedy was Aristophanes. His works define the legacy of Old Comedy, with their pungent political satire and abundance of sexual and scatological innuendo. Aristophanes lampooned the most important personalities and institutions of his day, as can be seen in his buffoonish portrayal of Socrates in The Clouds, and in his anti-military farce Lysistrata. In The Birds he held up Athenian democracy to ridicule. Only 11 of his plays have survived.

Lysistrata

Led by the title character, Lysistrata, the story's female characters barricade the public funds building and withhold sex from their husbands to end the Peloponnesian War and secure peace. In doing so, Lysistrata engages the support of women from Sparta, Boeotia, and Corinth. All of the other women are first against Lysistrata's suggestion to withhold sex. Finally, they agree to swearing an oath of allegiance by drinking wine from a phallic shaped flask, as the traditional implement (an upturned shield) would have been a symbol of actions opposed to the aims of the women. This action is ironic and therefore comical, because Greek men believed women had no self-restraint, a lack displayed in their alleged fondness for wine as well as for sex.

The Frogs

The Frogs had a more serious tone than some of Aristophanes other comedies. However, The Frogs is unique in its structure, because it combines two forms of comic motifs, a journey motif and a contest motif or agon motif, with each motif being given equal weight in the play.

Influence

The Old Comedy subsequently influenced later European writers such as Rabelais, Cervantes, Swift, and Voltaire. In particular, they copied the technique of disguising a political attack as buffoonery.

The legacy of Old Comedy can be seen in contemporary times in political satires such as Dr. Strangelove and in the televised buffoonery of Monty Python and Saturday Night Live.

Middle Comedy (mese)

The line between Old and Middle Comedy is not very clearly marked, Aristophanes and others of the latest writers of the Old Comedy becoming the earliest writers of the Middle Comedy. The Middle Comedy was an offshoot of the Old Comedy, but differed from it in three essential particulars: Middle Comedy had no chorus, public characters were not impersonated or personified on the stage, and the objects of ridicule were general rather than personal, literary rather than political. Where Old Comedy was caricature and lampoon, Middle Comedy was criticism and review.

The period of the Middle Comedy extended from the close of the Peloponnesian War to the enthrallment of Athens by Philip of Macedon; that is, from the closing years of the fifth century B.C.E. to nearly the middle of the fourth century B.C.E.. It was extremely prolific in plays, but not especially so in genius. The favorite themes were the literary and social peculiarities of the day, which, together with the prominent systems of philosophy, were treated with light and not ill-natured ridicule. The Middle Comedy freely parodied the grandest tragedies of Aeschylus and Sophocles, the noblest passages of Homer, and the most beautiful lyrics of Pindar and Simonides. Subjects taken directly from ancient mythology were treated in the same way. In dealing with society, classes rather than individuals were attacked, as courtesans, parasites, revelers, and especially the self-conceited cook, who, with his parade of culinary science, was always a favorite target for the shafts of middle comedy.

New Comedy (nea)

The new comedy lasted throughout the reign of the Macedonian rulers, ending about 260 B.C.E.

Very little of the text of the New Comedy has survived. A few Greek fragments have come down to us. During the twentieth century the complete text of Dyskolos, a play by Menander, the leading writer of New Comedy, was rediscovered. It is the only example of New Comedy to have survived in its entirety. A few long fragments by Menander have survived as well from such plays as The Arbitraton, The Girl from Samos, The Shorn Girl, and The Hero). Much of our information about the New Comedy is derived from the Latin adaptations by Plautus and Terence.

For the first time love became a principal element in the drama. The New Comedy relied on stock characters such as the senex iratus, or "angry old man," the domineering parent who is all too often led into the vices and follies for which he has reproved his son, and the bragging soldier or mercenary soldier newly returned from war with a noisy tongue, a full purse and an empty head. With these exceptions, the characters were very much the same as in the middle comedy. The new comedy represented Athenian society and the social morality of the period; but it made no attempt to improve it, presenting only in attractive colors.

The New Comedy influenced much of Western European literature, in particular the comic drama of Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, Congreve and Wycherley.[3]

Much of contemporary romantic and situational comedy descends from the New Comedy sensibility, in particular generational comedies such as All in the Family and Meet the Parents.

See also

- Agon at the Dionysia (mixed audiences) and Lenaia (local Athens audience only)

- Phallic processions

- Theatre of Dionysus

- Cult of Dionysus

List of Comic Dramatists

Some dramatists overlap into more than one period.

Old Comedy

- Susarion of Megara (~580 B.C.E.)

- Epicharmus of Kos (~540-450 B.C.E.)

- Cratinus (~520-420 B.C.E.)

- Chionides 486 B.C.E.

- Magnes 472 B.C.E.

- Eunicus Fifth c. BC

- Eupolis (~446-411 B.C.E.)

- Hegemon of Thasos Fifth century B.C.E.

- Telecleides Fifth century B.C.E.

- Pherecrates Fifth century B.C.E.

- Crates (comic poet) ca.450 century B.C.E.

- Hermippus 435 B.C.E.

- Phrynichus (~429 B.C.E.)

- Cantharus 422 B.C.E.

- Strattis (~412-390 B.C.E.)

- Cephisodorus 402 B.C.E.

- Plato (comic poet) late Fifth century B.C.E.

- Nicophon Fifth century B.C.E.

- Nicochares (d.~345 B.C.E.)

- Callias Schoenion

- Sannyrion

- Diocles of Phlius

- Aristophanes (~456–386 B.C.E.)

- His sons Araros, Philippus, and Nicostratus were also comic poets.

- Antiphanes (~408-334 B.C.E.)

Middle Comedy

- Eubulus early Fourth century B.C.E.

- Epicrates of Ambracia Fourth century B.C.E.

- Anaxandrides Fourth century B.C.E.

- Alexis (~375 B.C.E. - 275 B.C.E.)

- Menander (~342–291 B.C.E.)

New Comedy

- Philippides

- Philemon of Soli or Syracuse (~362–262 B.C.E.)

- Apollodorus of Carystus (~300-260 B.C.E.)

- Diphilus of Sinope (~340-290 B.C.E.)

- Machon of Corinth/Alexandria Third century B.C.E.

- Poseidippus of Cassandreia (~316–250 B.C.E.)

- Laines or Laenes 185 B.C.E.

- Philemon 183 B.C.E.

- Chairion or Chaerion 154 B.C.E.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aristotle. Poetics, lines beginning at 1449a Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- Bates, Alfred. The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, volume 1. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. OCLC 3711069

- Buckham, P.W. Theatre of the Greeks. Cambridge, Eng.: Printed by J. Smith, 1827. OCLC 4234970

- Cornford, F. M. The Origin of Attic Comedy. 1934. OCLC 431202

- Mastromarco, Giuseppe. 1994. Introduzione a Aristofane. Sesta edizione: Roma-Bari 2004. ISBN 8842044482

- Riu, Xavier. Dionysism and Comedy 1999. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- Old Comedy Retrieved August 18, 2008.

External links

All links retrieved July 26, 2023.

- An article on the origin of comedy

- "Aristotle on Comedy" by Malcolm Heath, University of Leeds.

- Comedy in Ancient Greek Theatre BBC Radio 4 "In Our Time" program on ancient Greek Comedy, Thursday 13 July 2006.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Ancient_Greek_Comedy history

- Lysistrata history

- The_Frogs history

- Comedy history

- Ancient_Greek_literature history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.