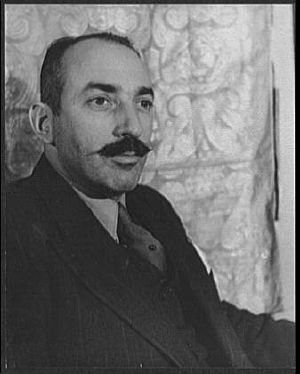

Alfred A. Knopf (person)

Alfred A. Knopf (September 12, 1892 – August 11, 1984) was a leading American publisher of the 20th century, founder of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.. Knopf began by emphasizing translations of great contemporary European literature, at that time neglected by American publishers, and specialized in producing books that were lauded for fine printing, binding, and design. His colophon, the borzoi, became synonymous with high quality books. He was honored in 1950 by the American Institute of Graphic Arts for his contribution to American book design.

His authors included 16 Nobel Prize laureates and 26 Pulitzer Prize winners. He was the first publisher to use photographs in testimonials, and he advertised books in spaces previously reserved for cars and cigarettes. Knopf was a great self promoter who wore flamboyant shirts from the most exclusive tailors; was a connoisseur of music, food, and wine; nurtured a garden of exotic plants; and enjoyed rare cigars. His self-assured, irascible manner, together with his insistence on the best of everything, shaped his house's image as a purveyor of works of enduring value.

After an excursion to the Western United States in 1948, Knopf became passionately interested in the national parks and forests, sparking his life-long activity in conservation issues. In 1950 he joined the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments of the National Park Service, serving as chairman for five years.

Alfred A. Knopf Inc. was virtually the last major firm of the old American publishing industry that included firms like Henry Holt and Company, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, and Ticknor and Fields. His company remained independent until 1960, when he sold it to Random House, Inc.. After several sales and mergers since then, the Knopf imprint still remains a respected force in book publishing.

Biography

Knopf was born into a Jewish family in New York City. His father Samuel Knopf was an advertising executive and financial consultant; his mother, Ida (Japhe) Knopf, died when he was four years old. He attended Columbia University, where he was a pre-law student and a member of the Peitholgian Society, a student run literary society.

His interest in publishing was allegedly fostered by a correspondence with British author John Galsworthy. After receiving his B.A. in 1912 he was planning to attend Harvard Law School the following fall. That summer, however, he traveled to England to visit Galsworthy. He would recommended the new writers W. H. Hudson and Joseph Conrad to Knopf and both would later play a role in Knopf's earliest publishing ventures.

Knopf gave up his plans for a law career and upon his return went into publishing. His first job was as a junior accountant at Doubleday (1912–13). While there he was one of the first to read Conrad's manuscript Chance. Enthusiastic about the novel and displeased with Doubleday's lackluster promotion, Knopf sent letters to well-known writers such as Rex Beach, Theodore Dreiser, and George Barr McCutcheon, asking for what would come to be known as "publicity blurbs." Additionally, Knopf's enthusiasm for Conrad led him to contact H. L. Mencken, also a Conrad admirer, initiating a close friendship that would last until Mencken's death in 1956.

In March 1914, Knopf left Doubleday to join Mitchell Kennerley's firm, in part because of Kennerley's commitment to good book design. While there Knopf wrote sales letters and sold books on the road.[1]

By 1915, at the age of twenty-three, Knopf was ready to strike out on his own.

Publishing career

He did his own typography, design, and manufacturing arrangements and by mid 1915 Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. issued its first volume, a collection of four translated play scripts by nineteenth century French playwright Émile Augier.[2]

With an initial investment of five thousand dollars he began to compete with older established firms, which already had under contract many established American authors. He initially looked abroad for fresh talent and as a result his first major success was Green Mansions by W. H. Hudson in 1916.

The same year Knopf married his assistant Blanche Wolf. Throughout the years, Blanche Knopf (1894-1966) played a decisive and influential role within the Knopf firm with regard to the direction it would take. Within a short period of time, the Knopf publishing firm was able to establish itself as a major force in the publishing world, attracting established writers from the States and abroad.[3]

The company's emphasis on European, especially Russian, literature resulted in the choice of the borzoi as a colophon. At that time European literature was largely neglected by American publishers. Knopf published authors such as Joseph Conrad, W. Somerset Maugham, D. H. Lawrence, E. M. Forster, Andre Gide, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, Thomas Mann, Sigmund Freud, and Franz Kafka.

By 1917, of the 77 books Knopf had issued, more than a quarter were English while continental, Russian, and Asian writers accounted for almost half. In the 1920s Knopf began acquiring such notable American authors as Willa Cather, Carl Van Vechten, and Joseph Hergesheimer.

Later Knopf would also publish many other American authors, including H. L. Mencken, Theodore Dreiser, Vachel Lindsay, James M. Cain, Conrad Aiken, Dashiell Hammett, James Baldwin, John Updike, and Shirley Ann Grau.

In the summer of 1918 he became president of the firm, a title he would hold for thirty-nine years. His imprint was respected for the intellectual quality of the books published under it, and the firm was widely praised for its clean book design and presentation. Though never the country’s largest publisher in terms of output or sales volume, Knopf’s Borzoi Books imprint developed a reputation for prestigious and scholarly works.[4]

Knopf's personal interest in the fields of history (he was a devoted member of the American Historical Association), sociology, and science also led to close friendships in the academic community with such noted scholars as Richard Hofstadter, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., R. R. Palmer, and Samuel Eliot Morison. Sixteen Knopf authors—the largest number of any American publishing house—won Nobel Prizes in literature.

Knopf himself was also an author. His writings include Some Random Recollections, Publishing Then and Now, Portrait of a Publisher, Blanche W. Knopf, July 30, 1894-June 4, 1966, and Sixty Photographs.

With Blanche's considerable literary acumen and the financial expertise of his father (who joined the firm in 1921 as treasurer and remained in that post until his death in 1932), Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. expanded rapidly during the 1920s and 1930s. In 1923, the firm published Khalil Gibran's The Prophet which became one of its most successful sellers.

When he was not invited to join the established publishing associations, he formed the Book Table, a luncheon group made up of publishers, book sellers, librarians, and other literary figures. Between 1924 and 1934 Knopf served as publisher of the iconoclastic magazine The American Mercury, edited until 1933 by H. L. Mencken.

In 1934, William A. Koshland joined the company, and remained associated with the firm for more than fifty years, rising to President and Chairman of the Board.

The firm weathered its first financial crisis in 1935. Book sales took a dramatic plunge after the introduction of sound to motion pictures in 1927 and reached a low-point for the century in 1933, then recovered somewhat to remain relatively flat during the rest of the decade.

Post-war success

World War II temporarily cut off American access to European writers. In the interim, Blanch Knopf became interested in Latin American writers. In 1942, Blanche Knopf visited South America, contacting authors and publishers. Three years later, the firm published the first of many texts from the region, Jorge Amado's The Violent Land.

At the end of World War II, Alfred Knopf turned over the European side of the business to Mrs. Knopf, and she traveled to the continent almost yearly. Among the writers she successfully courted were Elizabeth Bowen, Hammond Innes, Angela Thirkell, Alan Sillitoe, Mikhail Sholokhov, Mario Soldati, and Elinor Wylie. Mrs. Knopf read and selected manuscripts from all of Europe, but her most passionate interest lay in French literature. A life-long Francophile, she brought Albert Camus, Andre Gide, Jules Romains, and Jean-Paul Sartre to the firm. She was named a Chevalier de la Legion d'honneur by the French government in 1949, and became an Officier de la Legion d'honneur in 1960.[5]

The Knopfs hired their son, Alfred "Pat" Jr., as secretary and trade books manager after the war.

By 1945, as the country surged into the post-war prosperity, Knopf’s business flourished. After more than a quarter-century in publishing he had a well-earned reputation for quality book production and excellent writing.

The 1950s bring change

In 1954, Pat Knopf added Vintage Books, a paperback imprint, to the firm. Blanche Knopf became president of the firm in 1957. In 1959 Pat left to form his own publishing house, Atheneum.

Shortly after Par left, Alfred and Blanche Knopf decided to sell the firm to Random House in April 1960. In an agreement with long-time friends Bennett Cerf and Donald S. Klopfer, Random House took over much of the technical side of the business, but allowed the firm to retain its autonomy as an imprint. Alfred and Blanche Knopf also joined the Board of Directors at Random House. Knopf retained complete editorial control for five years, and then gave up only his right to veto other editors' manuscript selections. The editorial departments of the two companies remain separate, and Knopf, Inc., retains its distinctive character. Knopf called the merger "a perfect marriage."

After Blanche's death in 1966, William A. Koshland became president and two years later, Robert Gottlieb, formerly of Simon and Schuster, joined the firm as vice-president. Gottlieb became president and editor in chief after Alfred Knopf's official retirement in 1973. Gottlieb remained at Knopf until 1987, when Ajai Singh "Sonny" Mehta became president.

Later Random House, a subsidiary of RCA was subsequently bought by S. I. Newhouse and in turn it eventually became a division of Bertelsmann AG, a large multinational media company. The Knopf imprint had survived all the buyouts and mergers as of 2008.

Conservationist

On June 21, 1948 the Knopf's began a cross-country automobile trip that would prove to have an enormous influence on the rest of Alfred Knopf’s life. When they entered Yellowstone Alfred was deeply affected by the scope of the high plains and scenery of Yellowstone.

"The West has gotten in my blood something awful,” Knopf confessed candidly to Wallace Stegner, “I have just got to go out there again to make sure it's real."<ref>[

In the half-decade between 1949 and the mid 1950s Knopf made up for lost time in the Western outdoors. Though he had long been an avid skier and energetic golfer, he realigned his travel schedule to take in new section of the West. Every summer he planned a long working vacation in the West. Of course, he mixed business with pleasure, sandwiching dining arrangements with authors and prospective authors between hiking trips and long sightseeing drives. In five years he visited at least briefly every national park, national monument, and many major state parks between Glacier and the Big Bend, and from the hundredth meridian to the Oregon coast.15 13 Hersey, That meant the first step was to acquire book manuscripts that treated the subjects affecting most directly the West and its public lands and natural resources, and to acquire them contractually meant they had to be found Fortunately, his first westward trip piqued the publisher's interest just as the large California book market was gearing up for the state centennial. The anniversary provided a ready-made opening for drawing Knopf's newest passion into the firm’s book list Needing something in a hurry, Knopf approached Occidental College’s Robert G. Cleland about editing a reprint series of classic Western Americana 17The author was economics professor Morris E. Garnsey of the University of Colorado. Shugg felt the book was too academic for a commercial text in the college list and advised the editorial board to decline the book. Knopf asked for it immediately and after a close personal review wrote Garnsey directly. “I have now read, and with a great deal of interest, your manuscript AMERICA'S NEW FRONTIER By late April, 1949, Knopf had completely read Garnsey's “America's New Frontier” manuscript, which described many of the social and economic challenges facing the region and wrote to offer Garnsey a contract. Knopf’s effort to get qualified work on the national parks and western conservation into print was slow to bear fruit but he did not give up his search for suitable books on the West or its natural wonders and attractions. After nearly twenty years of ardent searching and comparatively few books to show for it, Knopf determined to try another tack and lure them out. At the 1963 Western Historical Society meeting in Salt Lake City, Knopf announced that he would award a $5,000 prize for books addressing the history of the West, with publication guaranteed and the award amount to be exclusive of royalties. Three years later, by the time he figured that manuscripts should be ready, he published the same announcement in an advertisement in the Western Historical Society Newsletter.28 In fact, the award was made only once, for John Hawgood’s America’s Western Frontiers. Part of the challenge was in the nature of academic writing of the time. While non-fiction was a respectable genre, academia was in the throes of the social history revolution. University presses were growing in sophistication and success In retrospect, Knopf’s most substantial contribution was not his publishing record but his work with conservation groups of the 1950s and 1960s. Between 1950 and 1975, in addition to the National Park Service board he served on the Sierra Club national advisory board, Trustees for Conservation, Citizens’ Committee on Natural Resources, the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, and many others. As both a staunch Republican and one of the most recognizable names in publishing, his word carried weight and opened doors where others were sometimes casually dismissed. He was decidedly pro-business in most matters, yet he did not give an inch when it came to criticizing exploitive private-industry legislation or federal largess to corporations. Having seen the isolated but spectacular Dinosaur National Monument up close, he was both attuned and incensed at the Bureau of Reclamation’s plans to flood Echo Park.37 Working with David Brower of the Sierra Club, the boards of several citizen conservation groups, nature photographer Charles Eggert and under the editorship of Wallace Stegner, Knopf produced This is Dinosaur!, a volume of photos, descriptive text, and a strongly worded conservation message that hardly mentioned the proposed dam Pressure from conservation groups, aided by newly awakened anti-tax organizations newly awakened to the high-cost/low-return project, finally killed the proposal.

However, by the mid 1960s, when he did have time to devote to personally supporting projects, age, a heart attack, and stroke limited direct participation. After 1960 Knopf was a Trustee member of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, a private group supporting preservation activities in and around New York City. Declining health slowing him considerably, Knopf tried to resign in 1974 but was persuaded to remain in his seat until the Society disbanded in 1976.47 After his sixty-fifth birthday, with his brief days of traveling adventurously behind him, Knopf became particularly active when local groups were taking the initiative.

Alfred A. Knopf was interested not at all in multiple-use policies or in recreation. He favoured the legal protections due parks over the usage rules which managed reserves, the values of preservation over the issues of conservation, and public rather than private stewardship. He was at heart a preservationist, willing to hold open huge tracts of public land for its own sake as open land.

Legacy

The Alfred A. and Blanche Knopf Library

Knopf also lamented the "shockingly bad taste" that he felt characterizes much modern fiction, and warned of the danger of a "legal backlash" against pornography, a possible revival of censorship.

This outspoken aspect of his character sometimes found voice in letters of complaint to hotels, restaurants, and stores that failed to meet his high standards. These letters grew increasingly frequent and more severe as he aged. One striking example is the six-year-long war of words he waged against the Eastman Kodak Company over a roll of lost film. [6].

Knopf's achievements as a publisher of distinguished books brought him half a dozen honorary degrees, as well as decorations from the Polish and Brazilian governments. In addition, his service on the advisory board of the National Parks Commission and his tireless efforts on behalf of conservation earned him numerous awards.

Bibliography

- John Tebbel, A History of Book Publishing in the United States, Volume II: The Creation of an Industry, 1865-1919 (1975); Volume III: The Golden Age Between Two Wars, 1920-1940 (1978);

- Bennett Cerf, At Random, Random House, 1977;

- Alfred A. Knopf, Some Random Recollections, Typophiles, 1949; Publishing Then and Now, New York Public Library, 1964; Portrait of a Publisher, Typophiles, 1965;

- New Yorker, November 20, 1948, November 27, 1948, December 4, 1948;

- Saturday Review, August 29, 1964, November 29, 1975;

- Publishers Weekly, January 25, 1965, February 1, 1965, May 19, 1975;

- Current Biography, Wilson, 1966;

- New York Times, September 12, 1972, September 12, 1977;

- New York Times Book Review, February 24, 1974;

- Saturday Review/World, August 10, 1974;

- W, October 31-November 7, 1975;

- Los Angeles Times, August 12, 1984;

- New York Times, August 12, 1984;

- Chicago Tribune, August 13, 1984;

- Newsweek, August 20, 1984;

- Time, August 20, 1984.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1925. The Borzoi 1925; being a sort of record of ten years of publishing. OCLC 406289

- Knopf, Alfred A. 1975. Sixty Photographs: To Celebrate the Sixtieth Anniversary of Alfred A. Knopf, Publisher. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0394498925

- Knopf, Alfred A. 1965. Portrait of a Publisher: 1915-1965 : Reminiscences and Reflections : Alfred A. Knopf and the Borzoi Imprint : Reflections and Appreciations. New York: The Typophiles. OCLC 65736739

External links

- Biographical Sketch.

- Brody, Seymour. A biography of Blanche W. Knopf, wife of Alfred A. Knopf. Jewish Virtual Library.

- Encyclopedia of World Biography

- Alfred Abraham Knopf

- The Borzoi 1920: Being a Sort of Record of Five Years' Publishing

- Blanche Wolf Knopf Encyclopedia.com.

- Usborne, David. 2007. Alfred A Knopf: How the great literary publisher proved to be the great rejecter

- Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Records, 1914-1961

- Saunders, Richard L. 2006. ALFRED A. KNOPF AND AMERICAN CONSERVATION

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.