Difference between revisions of "Adultery" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) (copied from wikipedia) |

(copied newer version from Wikipedia) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Law]] | [[Category:Law]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Sociology]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

'''Adultery''' is generally defined as consensual [[sexual intercourse]] by a [[marriage|married]] person with someone other than his or her lawful spouse. In many jurisdictions, an unmarried person who is sexually involved with a married person is also considered an adulterer. The common synonym for adultery is [[infidelity]] as well as unfaithfulness or in [[colloquial speech]], cheating. It was also known in earlier times by the legalistic term "alienation of affection".[http://www.thefreedictionary.com/alienation+of+affection] | '''Adultery''' is generally defined as consensual [[sexual intercourse]] by a [[marriage|married]] person with someone other than his or her lawful spouse. In many jurisdictions, an unmarried person who is sexually involved with a married person is also considered an adulterer. The common synonym for adultery is [[infidelity]] as well as unfaithfulness or in [[colloquial speech]], cheating. It was also known in earlier times by the legalistic term "alienation of affection".[http://www.thefreedictionary.com/alienation+of+affection] | ||

| Line 19: | Line 18: | ||

In [[Canadian]] law, adultery is defined under the [[Divorce Act]]. Though the written definition sets it as extramarital relations with someone of the opposite sex, the [[Civil Marriage Act|recent change in the definition of marriage]] gave grounds for a [[British Columbia]] judge to strike that definition down. In a 2005 case of a woman filing for divorce, her husband had cheated on her with another man, which the judge felt was equal reasoning to dissolve the union. | In [[Canadian]] law, adultery is defined under the [[Divorce Act]]. Though the written definition sets it as extramarital relations with someone of the opposite sex, the [[Civil Marriage Act|recent change in the definition of marriage]] gave grounds for a [[British Columbia]] judge to strike that definition down. In a 2005 case of a woman filing for divorce, her husband had cheated on her with another man, which the judge felt was equal reasoning to dissolve the union. | ||

| − | ==Adultery in selected | + | ==Adultery in selected cultural and religious traditions== |

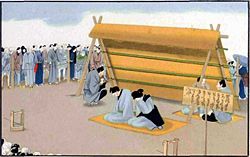

| + | [[Image:Man and woman undergoing public exposure for adultery in Japan-J. M. W. Silver.jpg|thumb|250px|Man and woman undergoing public exposure for adultery in Japan, around 1860]] | ||

| − | === | + | ===Primitive and Ancient societies=== |

| − | + | Among 'savages' generally adultery is rigorously condemned and punished. But it is condemned and punished only as a violation of the husband's rights. Among such peoples the wife is commonly reckoned as the property of her spouse, and adultery, therefore, is identified with theft. But it is theft of an aggravated kind, as the property which it would spoliate is more highly appraised than other chattels. So it is that in some parts of Africa the seducer is punished with the loss of one or both hands, as one who has perpetrated a robbery upon the husband (Reade, Savage Africa, p. 61). But it is not the seducer alone that suffers. Dire penalties are visited upon the offending wife by her wronged spouse in many instances she is made to endure such a bodily mutilation as will, in the mind of the aggrieved husband, prevent her being thereafter a temptation to other men (Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, I, 236; V, 683, 684, 686; also H.H. Bancroft, The Native Races of the Pacific States of North America, I, 514). If, however, the wronged husband could visit swift and terrible retribution upon the adulterous wife, the latter was allowed no cause against the unfaithful husband; and this discrimination found in the practices of savage peoples is moreover set forth in nearly all ancient codes of law. The Laws of Manu are Striking on this point. In ancient India, "though destitute of virtue or seeking pleasure elsewhere, or devoid of good qualities, yet a husband must be constantly worshipped as a god by a faithful wife"; on the other, hand, "if a wife, proud of the greatness of her relatives or [her own] excellence, violates the duty which she owes to her lord, the king shall cause her to be devoured by dogs in a place frequented by many" (Laws of Manu, V, 154; VIII, 371). | |

| − | In [[ | + | In the Graeco-Roman world we find stringent laws against adultery, yet almost throughout they discriminate against the wife. The ancient idea that the wife was the property of the husband is still operative. The lending of wives practiced among some savages was, as [[Plutarch]] tells us, encouraged also by Lycurgus, though, be it observed, from a motive other than that which actuated the savages (Plutarch, Lycurgus, XXIX). The recognized license of the Greek husband may be seen in the following passage of the Oration against Neaera, the author of which is uncertain, though it has been attributed to Demosthenes: "We keep mistresses for our pleasures, concubines for constant attendance, and wives to bear us legitimate children, and to be our faithful housekeepers. Yet, because of the wrong done to the husband only, the Athenian lawgiver Solon, allowed any man to kill an, adulterer whom he had taken in the act" (Plutarch, Solon). |

| − | + | In the early Roman Law the ''jus tori'' belonged to the husband. There was, therefore, no such thing as the crime of adultery on the part of a husband towards his wife. Moreover, this crime was not committed unless one of the parties was a married woman (Dig., XLVIII, ad leg. Jul.). That the Roman husband often took advantage of his legal immunity is well known. Thus we are told by the historian [[Spartianus]] that [[Verus]], the imperial colleague of [[Marcus Aurelius]], did not hesitate to declare to his reproaching wife: "Uxor enim dignitatis nomen est, non voluptatis." (Verus, V). | |

| − | In | + | |

| + | Later on in Roman history, as the late William E.H. Lecky has shown the idea that the husband owed a fidelity like that demanded of the wife must have gained ground at least in theory. This Lecky gathers from the [[legal maxim]] of [[Ulpian]]: "It seems most unfair for a man to require from a wife the chastity he does not himself practice" (Codex Justin., Digest, XLVIII, 5-13; Lecky, History of European Morals, II, 313). | ||

| − | + | ===Judaism=== | |

| + | In [[Judaism]], adultery was forbidden in the seventh commandment of the [[Ten Commandments]], but this did not apply to a married man having relations with an unmarried woman. Only a married woman engaging in sexual intercourse with another man counted as adultery, in which case both the woman and the man were considered guilty [http://www.studylight.org/enc/isb/view.cgi?word=adultery&search.x=0&search.y=0&search=Lookup&action=Lookup]. | ||

| − | [[ | + | In the [[Mosaic Law]], as in the old Roman Law, adultery meant only the carnal intercourse of a wife with a man who was not her lawful husband. The intercourse of a married man with a single woman was not accounted adultery, but [[fornication]]. The penal statute on the subject, in [[Leviticus]], xx, 10, makes this clear: "If any man commit adultery with the wife of another and defile his neighbor's wife let them be put to death both the adulterer and the adulteress" (see also [[Deuteronomy]] 22:22). This was quite in keeping with the prevailing practice of polygamy among the Israelites. |

| − | + | ||

| + | In [[halakha]] (Jewish Law) the penalty for adultery is stoning for both the man and the woman, but this is only enacted when there are two independent witnesses who warned the sinners prior to the crime being done. Hence this is rarely carried out, but a man is not allowed to continue living with a wife who cheated on him, and is obliged to give her a [[get (divorce document)|get]] or bill of divorce written by a [[sofer]] or scribe. | ||

| − | The | + | ===Christianity=== |

| + | This section considers adultery with reference to Catholic morality. The study of it, as more particularly affecting the bond of marriage, will be found under the head of Divorce. | ||

| − | + | ==== Nature of adultery==== | |

| + | Adultery is defined as carnal connection between a married person and one unmarried, or between a married person and the spouse of another. It is seen to differ from fornication in that it supposes the marriage of one or both of the agents. Nor is it necessary that this marriage be already consummated; it need only be what theologians call matrimonium ratum. Sexual commerce with one engaged to another does not, it is most generally held, constitute adultery. Again, adultery, as the definition declares, is committed in carnal intercourse. Nevertheless immodest actions indulged in between a married person and another not the lawful spouse, while not of the same degree of guilt, are of the same character of malice as adultery (Sanchez, De Mat., L. IX. Disp. XLVI, n. 17). However [[St. Alphonsus Liguori]], with most theologians, declares that even between lawful man and wife adultery is committed when their intercourse takes the form of [[sodomy]] (S. Liguori L. III, n. 446). | ||

| − | + | In the law of Jesus Christ regarding marriage the Mosaic discrimination against the wife is emphatically repudiated: the unfaithful husband loses his ancient immunity (Matthew 19:3-13). The obligation of mutual fidelity, incumbent upon husband as well as wife, is moreover implied in the notion of the Christian sacrament, in which is symbolized the ineffable and lasting union of the Heavenly Bridegroom and His unspotted Bride, the Church, St. Paul insists with emphasis upon the duty of equal mutual fidelity in both the marital partners (1 Corinthians 7:4); and several of the [[Fathers of the Church]], as [[Tertullian]] (De Monogamia, cix), [[Lactantius]] (Divin. Instit., LVI, c. xxiii), [[St. Gregory Nazianzen]] (Oratio, xxxi) and [[St. Augustine]] (De Bono Conjugati, n. 4), have given clear expression to the same idea. But the notion that obligations of fidelity rested upon the husband the same as upon the wife is one that has not always found practical exemplification in the laws of Christian states. Despite the protests of Mr. Gladstone, the English Parliament passed in 1857 a law by which a husband may obtain absolute divorce on account of simple adultery in his wife, while the latter can be freed from her adulterous husband only when his infidelity has been attended with such cruelty "as would have entitled her to a divorce a mensâ et toro." The same discrimination against the wife is found in some early [[New England]] colonies. Thus, in [[Massachusetts]] the adultery of the husband, unlike that of the wife, was not sufficient ground for divorce. And the same most likely was the case in Plymouth Plantation (Howard, A History of Matrimonial Institutions, II, 331-351). | |

| − | + | ====Guilt of adultery==== | |

| + | It is clear that the severity of punishment meted out to the adulterous woman and her seducer among savages did not find their sanction in anything like an adequate idea of the guilt of this crime. In contrast with such rigour is the lofty benignity of Jesus Christ towards the one guilty of adultery (John 8:3, 4), a contrast as marked as that between the Christian doctrine regarding the malice of this sin and the idea of its guilt which prevailed before the Christian era. In the early discipline of the Church we see reflected a sense of the enormity of adultery, though it must be admitted that the severity of this legislation, such as that, for instance, which we find in canons 8 and 47 of the [[Council of Elvira]] (c. 300), must be largely accounted for by the general harshness of the times. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Considering now the act in itself, adultery, forbidden by the sixth commandment, has in it a twofold malice, in common with fornication it violates chastity, and it is, besides, a sin against justice. Drawing a distinction between these two elements of malice, certain casuists, early in the seventeenth century, declared that intercourse with a married woman, when her husband gave his consent, constituted not the sin of adultery, but of fornication. It would, therefore, they contended, be sufficient for the penitent, having committed this act, to accuse himself of the latter sin only in confession. At the instance of the Archbishop of Mechlin, the Academy of Louvain, in the year 1653, censured as false and erroneous the proposition: "Copula cum conjugata consentiente marito non est adulterium, adeoque sufficit in confessione dicere se esse fornicatum." The same proposition was condemned by [[Innocent XI]] on March 2, 1679 (Denzinger, Enchir., p. 222, 5th ed.). The falsity of this doctrine appears from the very etymology of the word adultery, for the term signifies the going into the bed of another (St. Thom., II-II:154:8). And the consent of the husband is unavailing to strip the act by which another has intercourse with his wife of this essential characterization. Again, the right of the husband over his wife is qualified by the good of human generation. This good regards not only the birth, but the nourishment and education, of offspring, and its postulates cannot in any way be affected by the consent of parents. Such consent, therefore, as subversive of the good of human generation, becomes juridically void. It cannot, therefore, be adduced as a ground for the doctrine set forth in the condemned proposition above mentioned. For the legal axiom that an injury is not done to one who knows and wills it (scienti et volenti non fit injuria) finds no place when the consent is thus vitiated. | ||

| − | + | But it may be contended that the consent of the husband lessens the enormity of adultery to the extent that whereas, ordinarily, there is a double malice — that against the good of human generation and that against the private rights of the husband with the consent of the latter there is only the first-named malice; hence, one having had carnal intercourse with another's wife, her husband consenting, should in confession declare the circumstance of this permission that he may not accuse himself of that of which he is not guilty: In answer to this, it must be said that the injury offered the husband in adultery is done him not as a private individual but as a member of a marital society, upon whom it is incumbent to consult the good of the prospective child. As such, his consent does not avail to take away the malice of which it is question. Whence it follows that there is no obligation to reveal the fact of his consent in the case we have supposed (Viva, Damnatae Theses, 318). And here it may be observed that the consenting husband may be understood to have renounced his right to any restitution. | |

| − | + | The question has been discussed, whether in adultery committed with a Christian, as distinct from that committed with a Pagan, there would be special malice against the sacrament constituting a sin against religion. Though some theologians have held that such would be the case, it should be said, with Viva, that the fact that the sinful person was a Christian would create an aggravating circumstance only, which would not call for specification in confession. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | It need hardly be said that when the parties to adultery are both married the sin is more grievous than when one of them is single. Nor is it sufficient for a married person whose guilty partner in this act was also married to declare in confession the fact simply of having committed adultery. The circumstance that both parties to the sin were married is one that must be made known. Again the adulterer in his confession must specify whether, as married, he violated his own marriage pledge or; as single he brought about the violation of the marriage pledge of another. Finally, in case only one of the parties to adultery is married, a more heinous sin is committed when the married person is the woman than when she is the unmarried agent. For in the former instance the due process of generation is not infrequently interfered with, to the injury of the lawful husband; moreover, uncertainty of parentage may result, and even a false heir may be imposed upon the family. Such a distinction as is here remarked, therefore, calls for specification in the confessional. | |

| − | + | ==== Obligations of adulterers==== | |

| − | + | As we have seen, the sin of adultery implies an act of injustice committed against the lawful spouse of the adulterer or adulteress. By the adultery of a wife, besides the injury done the husband by her infidelity, a spurious child may be born which he may think himself bound to sustain, and which may perhaps become his heir. For the injury suffered in the unfaithfulness of his wife restitution must be made to the husband, should he become apprised of the crime. Nor is the obligation of this restitution ordinarily discharged by an award of money. A more commensurate reparation, when possible, is to be offered. Whenever it is certain that the offspring is illegitimate, and when the adulterer has employed violence to make the woman sin, he is bound to refund the expenses incurred by the putative father in the support of the spurious child, and to make restitution for any inheritance which this child may receive. In case he did not employ violence, there being on his part but a simple concurrence, then, according to the more probable opinion of theologians, the adulterer and adulteress are equally bound to the restitution just described. Even when one has moved the other to sin both are bound to restitution, though most theologians say that the obligation is more immediately pressing upon the one who induced the other to sin. When it is not sure that the offspring is illegitimate the common opinion of theologians is that the sinful parties are not bound to restitution. As for the adulterous mother, in case she cannot secretly undo the injustice resulting from the presence of her illegitimate child, she is not obliged to reveal her sin either to her husband or to her spurious offspring, unless the evil which the good name of the mother might sustain is less than that which would inevitably come from her failure to make such a revelation. Again, in case there would not be the danger of infamy, she would be held to reveal her sin when she could reasonably hope that such a manifestation would be productive of good results. This kind of issue, however, would be necessarily rare. | |

| − | + | ===Islam=== | |

| + | In [[Pakistan]] adultery is criminalized by a law called the [[Hudood Ordinance]], which specifies a maximum penalty of [[death penalty|death]], although only [[imprisonment]] and [[corporal punishment]] have ever actually been used. It is particularly controversial because a woman making an accusation of [[rape]] must provide extremely strong evidence to avoid being charged under it herself. | ||

| − | + | It is notable that same kinds of laws are in effect in some other Muslim countries also such as [[Saudi Arabia]]. However, in recent years high-profile rape cases in Pakistan have given [[Hudood Ordinance]] more exposure than similar laws in other countries. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | However, | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Sources and references== |

| − | + | *{{Catholic}} [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01163a.htm] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*Best Practices: Progressive Family Laws in Muslim Countries (August 2005} [http://usinfo.state.gov/mena/img/assets/4756/121305_muslim_family_laws.pdf] | *Best Practices: Progressive Family Laws in Muslim Countries (August 2005} [http://usinfo.state.gov/mena/img/assets/4756/121305_muslim_family_laws.pdf] | ||

*Hamowy, Ronald. ''Medicine and the Crimination of Sin: "Self-Abuse" in 19th Century America''. pp2/3 [https://www.mises.org/journals/jls/1_3/1_3_8.pdf] | *Hamowy, Ronald. ''Medicine and the Crimination of Sin: "Self-Abuse" in 19th Century America''. pp2/3 [https://www.mises.org/journals/jls/1_3/1_3_8.pdf] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | * [http://www.marriagebuilders.com/graphic/mbi5059_qa.html Coping with Infidelity] | |

| − | + | * [http://www.theravive.com/services/adultery_help.htm Adultery Help] | |

| − | + | * [http://www.divorcereform.org/stats.html Marital Statistics] | |

| − | * [http://www. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [http://www. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [http://www. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credit1|Adultery|77465492|}} |

Revision as of 21:57, 25 September 2006

Adultery is generally defined as consensual sexual intercourse by a married person with someone other than his or her lawful spouse. In many jurisdictions, an unmarried person who is sexually involved with a married person is also considered an adulterer. The common synonym for adultery is infidelity as well as unfaithfulness or in colloquial speech, cheating. It was also known in earlier times by the legalistic term "alienation of affection".[1]

The sexual partner of a person committing adultery is often referred to in legal documents, especially divorce proceedings, as a co-respondent, while the person whose spouse has been unfaithful is often labeled a cuckold. Originally, the latter term was applied only to males, but in more recent times women have been characterized in this way too.

A marriage in which both spouses agree that it is acceptable to have sexual relationships with other people is termed open marriage and the resulting sexual relationships, though still adulterous, are not treated as such by the spouses.

Penalties for adultery

Historically, adultery has been subject to severe sanctions including the death penalty and has been grounds for divorce under fault-based divorce laws. In some places the method for punishing adultery is stoning to death.[2]

In the original Napoleonic Code, a man could ask to be divorced from his wife if she committed adultery, but the adultery of the husband was not a sufficient motive unless he had kept his concubine in the family home.

In some jurisdictions, including Korea and Taiwan, adultery is still illegal. In the United States, laws vary from state to state. For example, in Pennsylvania, adultery is technically punishable by 2 years of imprisonment or 18 months of treatment for insanity (for history, see Hamowy). That being said, such statutes are typically considered blue laws, and are rarely, if ever, enforced. In the U.S. Military, adultery is a court-martialable offense only if it was "to the prejudice of good order and discipline" or "of a nature to bring discredit upon the armed forces" [3]. This has been applied to cases where both partners were members of the military, particularly where one is in command of the other, or one partner and the other's spouse. The enforceability of criminal sanctions for adultery is very questionable in light of Supreme Court decisions since 1965 relating to privacy and sexual intimacy, and particularly in light of Lawrence v. Texas, which apparently recognized a broad constitutional right of sexual intimacy for consenting adults.

In Canadian law, adultery is defined under the Divorce Act. Though the written definition sets it as extramarital relations with someone of the opposite sex, the recent change in the definition of marriage gave grounds for a British Columbia judge to strike that definition down. In a 2005 case of a woman filing for divorce, her husband had cheated on her with another man, which the judge felt was equal reasoning to dissolve the union.

Adultery in selected cultural and religious traditions

Primitive and Ancient societies

Among 'savages' generally adultery is rigorously condemned and punished. But it is condemned and punished only as a violation of the husband's rights. Among such peoples the wife is commonly reckoned as the property of her spouse, and adultery, therefore, is identified with theft. But it is theft of an aggravated kind, as the property which it would spoliate is more highly appraised than other chattels. So it is that in some parts of Africa the seducer is punished with the loss of one or both hands, as one who has perpetrated a robbery upon the husband (Reade, Savage Africa, p. 61). But it is not the seducer alone that suffers. Dire penalties are visited upon the offending wife by her wronged spouse in many instances she is made to endure such a bodily mutilation as will, in the mind of the aggrieved husband, prevent her being thereafter a temptation to other men (Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, I, 236; V, 683, 684, 686; also H.H. Bancroft, The Native Races of the Pacific States of North America, I, 514). If, however, the wronged husband could visit swift and terrible retribution upon the adulterous wife, the latter was allowed no cause against the unfaithful husband; and this discrimination found in the practices of savage peoples is moreover set forth in nearly all ancient codes of law. The Laws of Manu are Striking on this point. In ancient India, "though destitute of virtue or seeking pleasure elsewhere, or devoid of good qualities, yet a husband must be constantly worshipped as a god by a faithful wife"; on the other, hand, "if a wife, proud of the greatness of her relatives or [her own] excellence, violates the duty which she owes to her lord, the king shall cause her to be devoured by dogs in a place frequented by many" (Laws of Manu, V, 154; VIII, 371).

In the Graeco-Roman world we find stringent laws against adultery, yet almost throughout they discriminate against the wife. The ancient idea that the wife was the property of the husband is still operative. The lending of wives practiced among some savages was, as Plutarch tells us, encouraged also by Lycurgus, though, be it observed, from a motive other than that which actuated the savages (Plutarch, Lycurgus, XXIX). The recognized license of the Greek husband may be seen in the following passage of the Oration against Neaera, the author of which is uncertain, though it has been attributed to Demosthenes: "We keep mistresses for our pleasures, concubines for constant attendance, and wives to bear us legitimate children, and to be our faithful housekeepers. Yet, because of the wrong done to the husband only, the Athenian lawgiver Solon, allowed any man to kill an, adulterer whom he had taken in the act" (Plutarch, Solon).

In the early Roman Law the jus tori belonged to the husband. There was, therefore, no such thing as the crime of adultery on the part of a husband towards his wife. Moreover, this crime was not committed unless one of the parties was a married woman (Dig., XLVIII, ad leg. Jul.). That the Roman husband often took advantage of his legal immunity is well known. Thus we are told by the historian Spartianus that Verus, the imperial colleague of Marcus Aurelius, did not hesitate to declare to his reproaching wife: "Uxor enim dignitatis nomen est, non voluptatis." (Verus, V).

Later on in Roman history, as the late William E.H. Lecky has shown the idea that the husband owed a fidelity like that demanded of the wife must have gained ground at least in theory. This Lecky gathers from the legal maxim of Ulpian: "It seems most unfair for a man to require from a wife the chastity he does not himself practice" (Codex Justin., Digest, XLVIII, 5-13; Lecky, History of European Morals, II, 313).

Judaism

In Judaism, adultery was forbidden in the seventh commandment of the Ten Commandments, but this did not apply to a married man having relations with an unmarried woman. Only a married woman engaging in sexual intercourse with another man counted as adultery, in which case both the woman and the man were considered guilty [4].

In the Mosaic Law, as in the old Roman Law, adultery meant only the carnal intercourse of a wife with a man who was not her lawful husband. The intercourse of a married man with a single woman was not accounted adultery, but fornication. The penal statute on the subject, in Leviticus, xx, 10, makes this clear: "If any man commit adultery with the wife of another and defile his neighbor's wife let them be put to death both the adulterer and the adulteress" (see also Deuteronomy 22:22). This was quite in keeping with the prevailing practice of polygamy among the Israelites.

In halakha (Jewish Law) the penalty for adultery is stoning for both the man and the woman, but this is only enacted when there are two independent witnesses who warned the sinners prior to the crime being done. Hence this is rarely carried out, but a man is not allowed to continue living with a wife who cheated on him, and is obliged to give her a get or bill of divorce written by a sofer or scribe.

Christianity

This section considers adultery with reference to Catholic morality. The study of it, as more particularly affecting the bond of marriage, will be found under the head of Divorce.

Nature of adultery

Adultery is defined as carnal connection between a married person and one unmarried, or between a married person and the spouse of another. It is seen to differ from fornication in that it supposes the marriage of one or both of the agents. Nor is it necessary that this marriage be already consummated; it need only be what theologians call matrimonium ratum. Sexual commerce with one engaged to another does not, it is most generally held, constitute adultery. Again, adultery, as the definition declares, is committed in carnal intercourse. Nevertheless immodest actions indulged in between a married person and another not the lawful spouse, while not of the same degree of guilt, are of the same character of malice as adultery (Sanchez, De Mat., L. IX. Disp. XLVI, n. 17). However St. Alphonsus Liguori, with most theologians, declares that even between lawful man and wife adultery is committed when their intercourse takes the form of sodomy (S. Liguori L. III, n. 446).

In the law of Jesus Christ regarding marriage the Mosaic discrimination against the wife is emphatically repudiated: the unfaithful husband loses his ancient immunity (Matthew 19:3-13). The obligation of mutual fidelity, incumbent upon husband as well as wife, is moreover implied in the notion of the Christian sacrament, in which is symbolized the ineffable and lasting union of the Heavenly Bridegroom and His unspotted Bride, the Church, St. Paul insists with emphasis upon the duty of equal mutual fidelity in both the marital partners (1 Corinthians 7:4); and several of the Fathers of the Church, as Tertullian (De Monogamia, cix), Lactantius (Divin. Instit., LVI, c. xxiii), St. Gregory Nazianzen (Oratio, xxxi) and St. Augustine (De Bono Conjugati, n. 4), have given clear expression to the same idea. But the notion that obligations of fidelity rested upon the husband the same as upon the wife is one that has not always found practical exemplification in the laws of Christian states. Despite the protests of Mr. Gladstone, the English Parliament passed in 1857 a law by which a husband may obtain absolute divorce on account of simple adultery in his wife, while the latter can be freed from her adulterous husband only when his infidelity has been attended with such cruelty "as would have entitled her to a divorce a mensâ et toro." The same discrimination against the wife is found in some early New England colonies. Thus, in Massachusetts the adultery of the husband, unlike that of the wife, was not sufficient ground for divorce. And the same most likely was the case in Plymouth Plantation (Howard, A History of Matrimonial Institutions, II, 331-351).

Guilt of adultery

It is clear that the severity of punishment meted out to the adulterous woman and her seducer among savages did not find their sanction in anything like an adequate idea of the guilt of this crime. In contrast with such rigour is the lofty benignity of Jesus Christ towards the one guilty of adultery (John 8:3, 4), a contrast as marked as that between the Christian doctrine regarding the malice of this sin and the idea of its guilt which prevailed before the Christian era. In the early discipline of the Church we see reflected a sense of the enormity of adultery, though it must be admitted that the severity of this legislation, such as that, for instance, which we find in canons 8 and 47 of the Council of Elvira (c. 300), must be largely accounted for by the general harshness of the times.

Considering now the act in itself, adultery, forbidden by the sixth commandment, has in it a twofold malice, in common with fornication it violates chastity, and it is, besides, a sin against justice. Drawing a distinction between these two elements of malice, certain casuists, early in the seventeenth century, declared that intercourse with a married woman, when her husband gave his consent, constituted not the sin of adultery, but of fornication. It would, therefore, they contended, be sufficient for the penitent, having committed this act, to accuse himself of the latter sin only in confession. At the instance of the Archbishop of Mechlin, the Academy of Louvain, in the year 1653, censured as false and erroneous the proposition: "Copula cum conjugata consentiente marito non est adulterium, adeoque sufficit in confessione dicere se esse fornicatum." The same proposition was condemned by Innocent XI on March 2, 1679 (Denzinger, Enchir., p. 222, 5th ed.). The falsity of this doctrine appears from the very etymology of the word adultery, for the term signifies the going into the bed of another (St. Thom., II-II:154:8). And the consent of the husband is unavailing to strip the act by which another has intercourse with his wife of this essential characterization. Again, the right of the husband over his wife is qualified by the good of human generation. This good regards not only the birth, but the nourishment and education, of offspring, and its postulates cannot in any way be affected by the consent of parents. Such consent, therefore, as subversive of the good of human generation, becomes juridically void. It cannot, therefore, be adduced as a ground for the doctrine set forth in the condemned proposition above mentioned. For the legal axiom that an injury is not done to one who knows and wills it (scienti et volenti non fit injuria) finds no place when the consent is thus vitiated.

But it may be contended that the consent of the husband lessens the enormity of adultery to the extent that whereas, ordinarily, there is a double malice — that against the good of human generation and that against the private rights of the husband with the consent of the latter there is only the first-named malice; hence, one having had carnal intercourse with another's wife, her husband consenting, should in confession declare the circumstance of this permission that he may not accuse himself of that of which he is not guilty: In answer to this, it must be said that the injury offered the husband in adultery is done him not as a private individual but as a member of a marital society, upon whom it is incumbent to consult the good of the prospective child. As such, his consent does not avail to take away the malice of which it is question. Whence it follows that there is no obligation to reveal the fact of his consent in the case we have supposed (Viva, Damnatae Theses, 318). And here it may be observed that the consenting husband may be understood to have renounced his right to any restitution.

The question has been discussed, whether in adultery committed with a Christian, as distinct from that committed with a Pagan, there would be special malice against the sacrament constituting a sin against religion. Though some theologians have held that such would be the case, it should be said, with Viva, that the fact that the sinful person was a Christian would create an aggravating circumstance only, which would not call for specification in confession.

It need hardly be said that when the parties to adultery are both married the sin is more grievous than when one of them is single. Nor is it sufficient for a married person whose guilty partner in this act was also married to declare in confession the fact simply of having committed adultery. The circumstance that both parties to the sin were married is one that must be made known. Again the adulterer in his confession must specify whether, as married, he violated his own marriage pledge or; as single he brought about the violation of the marriage pledge of another. Finally, in case only one of the parties to adultery is married, a more heinous sin is committed when the married person is the woman than when she is the unmarried agent. For in the former instance the due process of generation is not infrequently interfered with, to the injury of the lawful husband; moreover, uncertainty of parentage may result, and even a false heir may be imposed upon the family. Such a distinction as is here remarked, therefore, calls for specification in the confessional.

Obligations of adulterers

As we have seen, the sin of adultery implies an act of injustice committed against the lawful spouse of the adulterer or adulteress. By the adultery of a wife, besides the injury done the husband by her infidelity, a spurious child may be born which he may think himself bound to sustain, and which may perhaps become his heir. For the injury suffered in the unfaithfulness of his wife restitution must be made to the husband, should he become apprised of the crime. Nor is the obligation of this restitution ordinarily discharged by an award of money. A more commensurate reparation, when possible, is to be offered. Whenever it is certain that the offspring is illegitimate, and when the adulterer has employed violence to make the woman sin, he is bound to refund the expenses incurred by the putative father in the support of the spurious child, and to make restitution for any inheritance which this child may receive. In case he did not employ violence, there being on his part but a simple concurrence, then, according to the more probable opinion of theologians, the adulterer and adulteress are equally bound to the restitution just described. Even when one has moved the other to sin both are bound to restitution, though most theologians say that the obligation is more immediately pressing upon the one who induced the other to sin. When it is not sure that the offspring is illegitimate the common opinion of theologians is that the sinful parties are not bound to restitution. As for the adulterous mother, in case she cannot secretly undo the injustice resulting from the presence of her illegitimate child, she is not obliged to reveal her sin either to her husband or to her spurious offspring, unless the evil which the good name of the mother might sustain is less than that which would inevitably come from her failure to make such a revelation. Again, in case there would not be the danger of infamy, she would be held to reveal her sin when she could reasonably hope that such a manifestation would be productive of good results. This kind of issue, however, would be necessarily rare.

Islam

In Pakistan adultery is criminalized by a law called the Hudood Ordinance, which specifies a maximum penalty of death, although only imprisonment and corporal punishment have ever actually been used. It is particularly controversial because a woman making an accusation of rape must provide extremely strong evidence to avoid being charged under it herself.

It is notable that same kinds of laws are in effect in some other Muslim countries also such as Saudi Arabia. However, in recent years high-profile rape cases in Pakistan have given Hudood Ordinance more exposure than similar laws in other countries.

Sources and references

- This article incorporates text from the public-domain Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913. [5]

- Best Practices: Progressive Family Laws in Muslim Countries (August 2005} [6]

- Hamowy, Ronald. Medicine and the Crimination of Sin: "Self-Abuse" in 19th Century America. pp2/3 [7]

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.