Matthias Grunewald

- The title of this article contains the character Ü. Where it is unavailable or not desired, the name may be represented as Matthias Gruenewald.

Matthias Grünewald or "Mathis" (as first name), "Gothart" or "Neithardt" (as surname), (c. 1470 – August 31, 1528), was an important German Renaissance painter of religious works, who ignored Renaissance classicism to continue the expressive and intense style of late medieval Central European art into the 16th century.

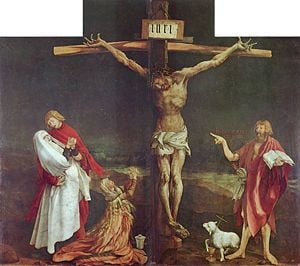

Only ten paintings (several consisting of many panels) and thirty-five drawings survive, all religious. Many others were lost in the Baltic Sea on their way to Sweden as war booty. His reputation was obscured until the late nineteenth century, and many of his paintings attributed to Albrecht Dürer, who is now seen as his stylistic antithesis. His largest and most famous work is the Isenheim Altarpiece in Colmar, Alsace (now in France).

Biography

The details of his life are unclear for a painter of his significance, despite the fact that his commissions show that he received reasonable recognition in his own lifetime. His real name remains uncertain, but was definitely not Grünewald; this was a mistake by the 17th-century writer, Joachim von Sandrart, 150 years after his death, who confused him with another artist. He is documented as "Master Mathis" or "Mathis the Painter" (Mathis der Maler), and as using the surnames Gothart and Neithardt - this last may have been his surname, or more likely that of his wife.

He was probably born in Würzburg between 1470 and 1475. It is possible he was a pupil of Hans Holbein the Elder. By 1500, he was a 'free master' and settled in the small town of Seligenstadt, where he bought a house with a pond and opened a workshop for painters and woodcarvers. His first dated painting is probably in Munich, dated 1503.

About 1510 Grünewald received a commission from the Frankfurt merchant Jacob Heller to add two fixed wings to the altarpiece of the Assumption of the Virgin recently completed by the painter Albrecht Dürer. These wings depicting four saints are painted in grisaille (shades of gray) and already show the artist at the height of his powers. Like Grünewald's drawings, which are done primarily in black chalk with some yellow or white highlighting, the Heller wings convey coloristic effects without the use of color. [1]

About 1515 Grünewald was entrusted with the largest and most important commission of his career. Guido Guersi, an Italian preceptor, or knight, who led the religious community of the Antonite monastery at Isenheim (in southern Alsace), asked the artist to paint a series of wings for the shrine of the high altar that had been carved in about 1505 by Nikolas von Haguenau of Strasbourg. The subject matter of the wings of the Isenheim Altarpiece provided Grünewald's genius with its fullest expression and was based largely on the text of the popular, mystical Revelations of St. Bridget of Sweden (written about 1370). [2]

Another important clerical commission came from a canon in Aschaffenburg, Heinrich Reitzmann. As early as 1513 he had asked Grünewald to paint an altar for the Mariaschnee Chapel in the Church of SS. Peter and Alexander in Aschaffenburg. The artist painted this work in the years 1517-19. Grünewald apparently married about 1519, but the marriage does not appear to have brought him much happiness (at least, that is the tradition recorded in the 17th century). Grunewald occasionally added his wife's surname, Neithardt, to his own, thereby accounting for several documentary references to him as Mathis Neithardt or Mathis Gothardt Neithardt.[3]

Works

Only religious works are included in his small surviving corpus, the most famous being the Isenheim Altarpiece, completed in 1515, now in the Musée d'Unterlinden, Colmar. Its nine images on twelve panels contain scenes of the Annunciation, Mary bathing Christ, Crucifixion, Entombment of Christ, Resurrection, Temptation of St. Anthony and saints.

As was common in the preceding century, there are different views, depending on the arrangement of the wings; but the three views available here are exceptional. The third view discloses a carved and gilded wood altarpiece in the center. As well as being by far his greatest surviving work, the altarpiece contains most of his surviving painting by area, being 2.65 meters high and over 5 meters wide at its fullest extent.

The Concert of Angels-Nativity panel is known as one of the great interpretive puzzles for critics and art historians. However, it is flanked by easily recognizable representations of the Annunciation and Resurrection. The composition is unique and has caused the efforts of scholars much grief in divining the depths of the meaning therein.

Grunewald's art is rooted in the irrational and mystical spiritual traditions of the medieval northern European art, compared to the cool logic of the Italian Renaissance, yet he produced an expressive 'realism' equaled only in modern times. He produced what he believed were crucial events in salvation history, presenting them symbolically, yet with realism. Grunewald was not adverse to altering Biblical versions of events to heighten the Christian message and his version of Christian truth was highly personal. His introduction of what appears to be Lucifer and other 'fallen' angels or dark spirits only adds to the realism of his work.

His other works are in Germany, except for a small Crucifixion in Washington, D.C. and another in Basel, Switzerland.

Dürer's work was destroyed by fire and only survives in copies, but fortunately the wings have survived. There is also the late Tauberbischofsheim altarpiece in Karlsruhe, and the Establishment of the Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome (1517-1519), Freiburg, Augustinermuseum. A large panel of Saint Erasmus and Saint Maurice in Munich probably dates from 1521-24, and was apparently part of a larger altarpiece project, the rest of which has not survived. Other works are in Munich, Karlsruhe, and Rhineland churches. Altogether four somber and awe-filled Crucifixions survive. The visionary character of his work, with its expressive color and line, is in stark contrast to Dürer's works. His paintings are known for their dramatic forms and depiction of light.

Legacy

The Protestant theologian Philipp Melanchthon is one of the few contemporary writers to refer to Grünewald, who is rather puzzlingly described as "moderate" in style, when compared with Dürer and Cranach; which paintings this judgment is based on is uncertain.

By the end of the century, when the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolph II embarked on his quest to secure as many Dürer paintings as possible, the Isenheim Altarpiece was already generally believed to be a Dürer. In the late 19th century he was rediscovered, and became something of a cult figure, with the angst-laden expressionism, and absence of any direct classicism. The Isenheim Altarpiece appealed to both German Nationalists and Modernists.

Joris-Karl Huysmans promoted his art enthusiastically in both novels and journalism, rather as Proust did for Vermeer. His apparent sympathies with the peasants in the Peasants' War also brought him admiration from the political left. Elias Canetti wrote his novel Auto-da-Fé surrounded by reproductions of the Isenheim altarpiece stuck to the wall.

The composer Paul Hindemith based his 1938 opera Mathis der Maler on the life of Grünewald during the Peasants' War; scene Six includes a partial re-enactment of some scenes from the Isenheim Altarpiece.

He is commemorated as an artist and quasi-saint by the Lutheran Church on April 6, along with Dürer and Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Gallery

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burkhard, Arthur. 1976. Matthias Grünewald: Personality and Accomplishment. New York: Hacker Art Books. ISBN 087817186X

- Cuttler, Charles D. 1986. Northern Painting: from Pucelle to Bruegel/Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Sixteenth centuries. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 003089476X

- Grünewald, Matthias, and J.-K. Huysmans. 1976. Grünewald. Oxford: Phaidon. ISBN 0714817511

- Hayum, Andrée. 1989. The Isenheim Altarpiece: God's Medicine and the Painter's Vision. Princeton essays on the arts, 18. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691040702

- Mellinkoff, Ruth. 1988. The Devil at Isenheim: Reflections of Popular Belief in Grünewald's Altarpiece. California studies in the history of art, 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520062043

- Ziermann, Horst, and Matthias Grünewald. 2001. Matthias Grünewald. Munich: Prestel. ISBN 3791325000

External links

- Late Gothic Painting Ibiblio.org.

- Matthias Grünewald's Works of Art Museumsyndicate.com.

- German Northern Renaissance Painter Artcyclopedia.com.

- Biography Wga.hu.

- Grunewald Artchive.com.

- Matthias Grünewald Cgfa.sunsite.dk.

- Jones, Jonathan. 2007. Who was Matthias Grünewald? Guardian.co.uk.

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Grünewald, Matthias |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gothart-Nithart, Mathis;Gruenewald, Matthias |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | German Renaissance painter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | |

| DATE OF DEATH | 31 August 1528 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Halle (Saale) |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.