Difference between revisions of "Czechoslovakia" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

[[Image:Czechoslovakia01.png|thumb|left|200px|Czechoslovakia in 1928]] | [[Image:Czechoslovakia01.png|thumb|left|200px|Czechoslovakia in 1928]] | ||

| − | === | + | ==World War II== |

| − | + | ===End of the State=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Munich Agreement, which deprived Czechoslovakia of one-third of its territory, mainly the Sudetenland, was signed on September 29, 1938, by the representatives of Germany—Adolf Hitler, Great Britain—Neville Chamberlain, Italy—Benito Mussolini, and France—Édouard Daladier. The Sudetenland was crucial to Czechoslovakia as most of its elaborate and costly border defences were situated there and ethnic Germans formed a majority of its population. Many Sudeten Germans rejected affiliation with Czechoslovakia because their right to self-determination pledged by US president Wilson in his Fourteen Points of January 1918 had not been honored by the Czechoslovak government. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Hitler thus defeated Czechoslovakia without armed action and without Czechoslovakia’s participation in the deal. 1,200,000 Czechs and Slovaks living in the Sudetenland areas were forced to leave their homes within ten days. Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš resigned on October 5, 1938, and Emil Hácha, a highly respected independent and lawyer by training, was appointed president. On March 14, 1939, Hácha set out for Berlin to meet with Adolf Hitler; the same day, Slovakia declared independence, which served Hitler well and provided him with a pretext to declare that Czechoslovakia had collapsed from within and thus occupation of Bohemia and Moravia would forestall a chaos in Central Europe. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [ | + | The Czechoslovak President described the signing away Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, for which he had been referred to as traitor of the nation, as follows: “You can withstand Hitler’s yelling, because you are not necessarily a devil for yelling. But Göring, with his jovial face, was there as well. He took me by the hand and softly reproached me, asking whether it is really necessary for the beautiful Prauge to be leveled in a few hours… and I could tell that the devil, who is capable of carrying out his threat, was speaking to me.” The Czechoslovak President was also asked the following by Göring: “You don’t want or can’t understand the Führer, who wishes that lives of thousands of Czech people are spared?” He had been subjected to enormous psychological pressure, in the course of which he collapsed. The next morning, Wehrmacht occupied what remained of Czechoslovakia. After Hitler personally inspected the Czech fortifications, he privately admitted that ‘We would have shed a lot of blood.[4] [Czechoslovakia’s factories thus began churning out products for the Third Reich. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===The World War II period=== | ===The World War II period=== | ||

| Line 219: | Line 151: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===After 1989 === | ===After 1989 === | ||

Revision as of 04:33, 20 May 2007

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

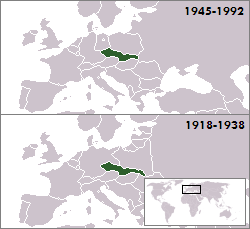

Czechoslovakia (Czech and Slovak: Československo, or (increasingly after 1990) in Slovak Česko-Slovensko) was a country in Central Europe that existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992 (with a government-in-exile during the World War II period). On January 1, 1993, Czechoslovakia peacefully split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Transportation and communications, Education, Religion, Health, social welfare and housing, Mass Media, Sports and Culture.

Basic Facts

Form of statehood:

- 1918–1938: democratic republic

- 1938–1939: after annexation of the Sudetenland region by Germany in 1938, Czechoslovakia turned into a state with loosened connections between its Czech, Slovak and Ruthenian parts. A large strip of southern Slovakia and Ruthenia was annexed by Hungary, and the Zaolzie region went under Poland's control

- 1939–1945: split into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and Slovakia (1939-1945). De jure Czechoslovakia continued to exist, with the exiled government, recognized by the Western Allies, based in London. Following the German invasion of Russia, the USSR recognized the exiled government as well.

- 1945–1948: democracy, governed by a coalition government, with Communist ministers setting the course

- 1948–1989: Communist state with a centrally planned economy

- from 1960 on the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

- 1969–1990: a federal republic consisting of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic

- 1990–1992: a federal democratic republic consisting of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic

Neighbours: West Germany and East Germany, Poland, Soviet Union, Ukraine), Hungary, Romania, and Austria.

Official Names

- 1918–1920: Czecho-Slovak Republic or Czechoslovak Republic (abbreviated RČS); short form Czecho-Slovakia or Czechoslovakia

- 1920–1938 and 1945–1960: Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR); short form Czechoslovakia

- 1938–1939: Czecho-Slovak Republic; Czecho-Slovakia

- 1960–1990: Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR); Czechoslovakia

- April 1990: Czechoslovak Federative Republic (Czech version) and Czecho-Slovak Federative Republic (Slovak version),

- afterwards: Czech and Slovak Federative Republic (ČSFR, with the short forms Československo in Czech and Česko-Slovensko in Slovak)

History

Foundation

Czechoslovakia came into existence in October 1918 as one of the successor states of Austria-Hungary following the end of World War I. It comprised the present-day Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia and some of the most industrialized regions of the former Austria-Hungary. Until the outbreak of World War II, it was a democratic republic, albeit with ethnic tensions stemming from the dissatisfaction of Germans and Slovaks, the second and third largest ethnic groups, respectively, with the political and economic dominance of the Czechs. Moreover, most ethnic Germans and Hungarians never accepted the creation of the new state. These ethnic groups, including Ruthenians and Poles, felt disadvantaged within Czechoslovakia, because the country's political elite introduced a centralized state and was reluctant to safeguard political autonomy for the ethnic groups. This policy, combined with an increasing Nazi propaganda, particularly in the industrialized German speaking Sudetenland, fueled the growing unrest among the Non-Czech population.[1]) and also some Slovaks,

World War II

End of the State

The Munich Agreement, which deprived Czechoslovakia of one-third of its territory, mainly the Sudetenland, was signed on September 29, 1938, by the representatives of Germany—Adolf Hitler, Great Britain—Neville Chamberlain, Italy—Benito Mussolini, and France—Édouard Daladier. The Sudetenland was crucial to Czechoslovakia as most of its elaborate and costly border defences were situated there and ethnic Germans formed a majority of its population. Many Sudeten Germans rejected affiliation with Czechoslovakia because their right to self-determination pledged by US president Wilson in his Fourteen Points of January 1918 had not been honored by the Czechoslovak government.

Hitler thus defeated Czechoslovakia without armed action and without Czechoslovakia’s participation in the deal. 1,200,000 Czechs and Slovaks living in the Sudetenland areas were forced to leave their homes within ten days. Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš resigned on October 5, 1938, and Emil Hácha, a highly respected independent and lawyer by training, was appointed president. On March 14, 1939, Hácha set out for Berlin to meet with Adolf Hitler; the same day, Slovakia declared independence, which served Hitler well and provided him with a pretext to declare that Czechoslovakia had collapsed from within and thus occupation of Bohemia and Moravia would forestall a chaos in Central Europe.

The Czechoslovak President described the signing away Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, for which he had been referred to as traitor of the nation, as follows: “You can withstand Hitler’s yelling, because you are not necessarily a devil for yelling. But Göring, with his jovial face, was there as well. He took me by the hand and softly reproached me, asking whether it is really necessary for the beautiful Prauge to be leveled in a few hours… and I could tell that the devil, who is capable of carrying out his threat, was speaking to me.” The Czechoslovak President was also asked the following by Göring: “You don’t want or can’t understand the Führer, who wishes that lives of thousands of Czech people are spared?” He had been subjected to enormous psychological pressure, in the course of which he collapsed. The next morning, Wehrmacht occupied what remained of Czechoslovakia. After Hitler personally inspected the Czech fortifications, he privately admitted that ‘We would have shed a lot of blood.[4] [Czechoslovakia’s factories thus began churning out products for the Third Reich.

The World War II period

MUNICH TREASON, HEYDRICH'S ASSASSINATION, DEPORTS OF JEWS, COLLABORATION WITH GESTAPO, PARATROOPERS, ENGLAND

Following the German annexation of Austria with the Anschluss, Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland (the German-border regions of Bohemia and Moravia) would be Adolf Hitler's next demand. In accordance with the Munich Agreement, Wehrmacht troops occupied the Sudetenland in October 1938. The greatly weakened Czechoslovak Republic was forced to grant major concessions to the non-Czechs, creating autonomous republics in Slovak and Ruthenia. In November, the First Vienna Award gave Hungary territory in southern Slovakia. Finally Czechoslovakia ceased to exist in March 1939, when Hitler occupied the remainder of the Czech lands and (the remaining) Slovakia declared independence. During the World War II the Czech lands were designated the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and were ruled directly by the German state. The newly independent Slovak Republic became an ally of Nazi Germany. Slovakia's troops fought on the Russian front until the summer of 1944, when the Slovak armed forces staged an uprising against their government. German forces crushed this uprising after several weeks of fighting.

During World War II a Czechoslovak government-in-exile was established in London by Edvard Beneš, who was recognised as President of Czechoslovakia by the British and other Allied governments. He returned to power as President when Czechoslovakia was liberated in 1945 and was re-elected in 1946.

Československo na přelomu let 1938/39 podlehlo německé agresi. Po vypuknutí druhé světové války se pod vedením československé zahraniční vlády začaly formovat československé zahraniční jednotky. Vstupovali do nich dobrovolně utečenci z Protektorátu, českoslovenští občané žíjící trvale v zahraničí aj. První jednotka se utvořila v Polsku, kde však pro nedokončený výcvik nezasáhla do bojů a byla internována Rusy. Ve Francii se utvořila 1. čs. divize, která měla 10 000 příslušníků, ale během rychlé porážky Francie se jen její dva pluky účastnily ústupových bojů a byla spěšně bez výzbroje evakuována do Británie......

Počátek války přivítal český domácí občanský odboj s nadějemi na brzké obnovení samostatnosti Československa. Vlna odporu, která se rozšířila v českém národě a kterou nezastrašilo ani preventivní zatýkání předpokládaných odpůrců nacismu v rámci akce Albrecht I. (1. září 1939), vyvrcholila masovými demonstracemi 28. října 1939. V Praze došlo k rozsáhlým srážkám demonstrantů s okupační mocí, při kterých byl zastřelen dělník Václav Sedláček a smrtelně raněn student medicíny Jan Opletal. Jeho pohřeb se stal příležitostí k dalším spontánním masový, demonstracím. Nacistická moc na ně reagovala terorem zaměřeným v prvé řadě proti studentům. 17. listopadu bylo v Praze popraveno bez soudu devět studentských funkcionářů, české vysoké školy byly uzavřeny a do koncentračního tábora bylo odvlečeno na 1200 vysokoškolských studentů. Masová vystoupení proti okupantům vzbudila pozornost a represe okupantů pobouření v celém demokratické světě. Brutální teror ukázal, že další otevřené střety s okupační mocí nejsou možné. Občanský odboj se proto soustředil na vytváření dalších ilegálních organizací a jejich propojování do odbojových sítí. Cílem občanského odboje se stala obnova samostatného Československa. Vojenská odbojová organizace Obrana národa připravovala od začátku války masové ozbrojené vystoupení proti okupantům, národní povstání, ke kterému mělo podle plánů dojít v okamžiku, kdy se přiblíží porážka Německa. Teritoriálně organizovaná síť Obrna národa, podřízená ústřednímu velení v čele s generálem Josefem Bílým, počítala pro povstání s účastí asi 80 000 mužů. Sílily také ostatní odbojové organizace. Na jaře roku 1940 se občanské odbojové organizace spojily a vytvořily Ústřední vedení odboje domácího- ÚVOD, které tvořili zástupci Petičního výboru Věrni zůstaneme, Obrany národa a Politického ústředí. Občanský odboj přecházel postupně od organizační práce, vydávání a rozšiřování periodik a letáků k aktivním formám odboje. Vynikajících výsledků dosáhli na tiché frontě českoslovenští zpravodajci, kteří dodávali informace politického, hospodářského i vojenského charakteru do VB i SSSR. Roku 1941 vyvrcholila aktivita českých odbojových organizací. Došlo k celé řadě stávek, vzrostl počet sabotáží, bylo přerušováno telefonní a telegrafní vedení, poškozována vojenská technika narušována železniční doprava. S úkolem pacifikovat rozbouřenou situaci v protektorátu byl koncem září 1941 vyslán do Prahy jako zastupující říšský protektor obergruppenfürer ss a generál policie Reinhard Heydrich, šéf Hlavního úřadu říšské bezpečnosti, který zavedl politiku cukru a biče. Po jeho příchodu bylo vyhlášeno stanné právo, během jehož trvání bylo do ledna 1942 popraveno 500 lidí. Začalo také masové zatýkání, které vážně narušilo ilegální odbojové sítě, v říjnu 1941 byl rozbil i Ústřední národně revoluční výbor Československa. Na pomoc decimovanému domácímu odbojovému hnutí začaly být od poloviny roku 1941 vysílány do protektorátu parašutistické výsadky z VB. Měly za úkol obnovení přerušeného rádiového spojení mezi domácím a zahraničním odbojem, obnovu přetrhaných odbojových a zpravodajských sítí, v některých případech i sabotáž. Zvláštním úkolem byla pověřena skupina Anthropoid, jejíž členové Kubiš a Gabčík provedli 27. května 1942 v Praze atentát na Heydricha. Tento čin sice posílil prestiž Československa ve světě, smrt zastupujícího říšského protektora 4. června byla však úvodem k německým represáliím. Znovu bylo vyhlášeno stanné právo, kterému tentokrát padlo za oběť 1600 lidí. Dalších 3000 osob nacisté povraždili v koncentračních táborech. Po rozbití ilegálních sítí v období heydrichiády se již občanskému odboji nepodařilo obnovit svou činnost v rozsahu let 1940-41. Počátkem roku 1943 bylo navíc definitivně rozbito Ústřední vedení odboje domácího a přes snahu řady občanských odbojových organizací se nepodařilo vytvořit nový centrální orgán. Přípravný revoluční národní výbor nedokázal v letech 1943-44 plně rozvinout svou činnost a ani odbojové organizaci Rada tří se nepodařilo sjednotit občanské odbojové skupiny.Velkým problémem zůstávalo rádiové spojení domácího odboje s československou v Londýně, přestože do protektorátu byla za tímto účelem vysazena celá řada parašutistických výsadků. Příčinou oslabení odbojového hnutí byly především zásahy nacistického bezpečnostního aparátu, jehož nejvýznamnější složkou bylo gestapo, tajná státní policie. Němci měli k dispozici zkušený kvalifikovaný personál, vybavený moderními technickými prostředky. Rádiová zaměřovací služba pátrala po vysílačkách a často jejich odhalení využívala ke zpravodajským protihrám s Londýnem i Moskvou, při kterých se snažila oklamat protivníka a získat informace.

PŘIDEJTE SVŮJ REFERÁT

Druhý československý odboj, úloha tzv. Tří králů a odbojová role doc. Vladimíra Krajiny

Ve všech evropských okupovaných zemích z let 1939-45 začínal postupně vznikat odboj jako projev nevůle a odporu proti okupačním poměrům. Měl svou specifikaci podle jednotlivých zemích – Polsko, Jugoslávie, SSSR, Protektorát Čechy a Morava. Náš národ německou okupační vládu nikdy nepřijal. Etapy národního odboje

Odboj měl u nás tři etapy:

1. do příchodu Heydricha 2. po 27.9.1941 – Heydrichův příchod 3. po Heydrichově smrti.

Odboj se také podílel na konečném osvobození naší země. Jeho vrchol spadal do let 1939-41, kdy měl různé fáze a vynalézavé formy.

Druhý československý odboj je největší mravní hodnota, jež české země ve 20. století prožily. Sešel se na něj takřka celý národ. První a třetí odboj byly taky hrdinské, ale první nereprezentoval celý národ, ve třetím šlo mnoho Čechů s KSČ.

V první etapě (před příchodem Heydricha) vznikl na jaře 1940 ÚVOD, řada činitelů – Drtina, Feierabend – odešla do emigrace. Dva subjekty: „tři králové“ (mušketýři) a Krajina – ne vždy spolupracovali.

Tři mušketýři: pplk. Josef Balabán, pplk. Josef Mašín (velitel pluku v Ruzyni) – předváleční velitelé a legionáři a štábní kapitán Václav Morávek – člověk velmi vzdělaný. V průběhu r. 1940 a na jaře 1941 měli dva úkoly:

* vykonávat sabotážní činnost na celém území protektorátu. Gestapo o nich vědělo, ale neznalo jejich jména a pobyty. * získávání zpráv o stavu protektorátu a okupační armády. Údaje měli předávat Krajinovi – měl šifrovací oddělení, předával je Benešovi do Londýna.

Oznámili tak přepadení Francie, SSSR a další věci. Dochází zde ke vzniku konfliktů mezi „třemi králi“ a Krajinou – Krajina si je upravoval pro odvysílání – oni nesouhlasili. Od přelomu let 1940/41 dostali nové, velmi nebezpečné zadání z Londýna. Měli navázat kontakt s předválečným československým agentem německé národnosti Paulem Thümelem (agent A54), s nímž naše rozvědka spolupracovala již před válkou, pobýval v Praze. Navázali kontakt – tím se jejich zprávy zkvalitnily, ale došlo k jejich většímu ohrožení, protože agentu A54 přišlo gestapo na stopu. V dubnu 1941 je zatčen Balabán a v květnu 1941 Mašín. Balabán je na podzim popraven, Mašín později za heydrichiády. Morávek celý r. 1941 přežil, s agentem A54 kontaktoval dál, zastřelil se v důsledku zrady 21.3.1942. Měl se tam setkat s odbojářem, ale místo něho přišlo gestapo. Zemřel po převozu do nemocnice.

Krajina: nakonec byl prezidentem Havlem v r. 1993 oceněn řádem Bílého lva. Jeho posláním bylo posílat depeše do Londýna, které byly velmi oceňovány. Poslal jich 30-50 tisíc. Žil v ilegalitě, naposled u rodiny Drašnerovy v Praze. Gestapo o něm také vědělo. Před heydrichiádou měl řadů kontaktů. Za heydrichiády byl pro něj pobyt v Praze velmi nebezpečný. 16.6.1942 odchází do severovýchodních Čech do oblasti Trosek, Kocanova – ukrýval se tam. Naposledy u řídícího učitele Hlaváčka ve Veselí. Přepažením třídy mu udělá malou místnůstku. Hledali ho tam a nenašli. Vytipovali si lidi, kde by se mohl skrývat. Hlaváček byl zatčen na počátku r. 1943, Krajina utekl, schoval se na faře v Trutnově. Nasadili na něj agenty, přivezli paní Krajinovou z koncentračního tábora.

V neděli 31.1.1943 ho na faře zatkli, požil cyankáli, které bylo prošlé, rozředili ho dvěma litry mléka. Odvezli ho k výslechu do Prahy – zúčastnil se ho i K.H.Frank. Bylo mu nabídnuto, aby se stal členem protektorátní vlády – odmítl. I s manželkou byl uvězněn v Terezíně. Na konci války převezen na Jenerálku u Prahy. 7.5.1945 je osvobozen. Komunisté proti němu využili jeho pobyt v Terezíně (nebyla mu prokázána kolaborace). Stal se generálním tajemníkem Národně socialistické strany. Po únoru 1948 ve 43 letech opustil republiku – nejprve do Londýna a poté do Kanady. Vrátil se k profesi botanika, biologa – některé ekosystémy jsou po něm pojmenovány.

Communist Czechoslovakia

CHARTA 77, DISSIDENTS, HAVEL, DIENSTBIER

After World War II, pre-war Czechoslovakia was reestablished, The Beneš decrees concerned the expropriation of wartime "traitors" and collaborators accused of treason but also all ethnic Germans (see Potsdam Agreement) and Hungarians. They also ordered the removal of citizenship for people of German and Hungarian ethnic origin who decided to acquire the German and Hungarian citizenship during the occupation. (These provisions were cancelled for the Hungarians, but not for the Germans, in 1948). This was then used to confiscate their property and expel around 90% of the ethnic German population of Czechoslovakia. The people who remained were collectively accused of supporting the Nazis (after the Munich Agreement, in December 1938, 97.32% of adult Sudetengermans voted for NSDAP in elections). Almost every decree explicitly stated that the sanctions did not apply to anti-fascists although the term Anti-fascist was not explicitly defined. Some 250,000 Germans, many married to Czechs, some anti-fascists, but also people required for the post-war reconstruction of the country remained in Czechoslovakia. The Benes Decrees still cause controversy between nationalist groups in Czech Republic, Germany, Austria and Hungary. [2].

Carpathian Ruthenia was occupied by (and in June 1945 formally ceded to) the Soviet Union. In 1946 parliamentary election the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia emerged as the winner in the Czech lands (the Democratic Party won in Slovakia). In February 1948 the Communists seized power. Although they would maintain the fiction of political pluralism through the existence of the National Front, except for a short period in the late 1960s (the Prague Spring) the country was characterized by the absence of liberal democracy. While its economy remained more advanced than those of its neighbors in Eastern Europe, Czechoslovakia grew increasingly economically weak relative to Western Europe. In the religious sphere, atheism was officially promoted and taught. In 1969, Czechoslovakia was turned into a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic. Under the federation, social and economic inequities between the Czech and Slovak halves of the state were largely eliminated. A number of ministries, such as Education, were formally transferred to the two republics. However, the centralized political control by the Communist Party severely limited the effects of federalization.

The 1970s saw the rise of the dissident movement in Czechoslovakia, represented (among others) by Václav Havel. The movement sought greater political participation and expression in the face of official disapproval, making itself felt by limits on work activities (up to a ban on any professional employment and refusal of higher education to the dissidents' children), police harassment and even prison time.

After 1989

http://www.totalita.cz/1989/1989_11.php

ROLE OF STUDENTS IN REVOLUTION; ARTISTS, OBCANSKE FORUM, HAVEL

In 1989, the country became democratic again through the Velvet Revolution. In 1992 the growing nationalist tensions led to dissolution of Czechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and Slovakia, as of January 1, 1993.

Government

Heads of state

- List of Presidents of Czechoslovakia

- List of Prime Ministers of Czechoslovakia

International agreements and membership

After WWII, active participant in Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), Warsaw Pact, United Nations and its specialized agencies; signatory of conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

Administrative divisions

Main article: Administrative divisions of Czechoslovakia

- 1918–1923: different systems on former Austrian territory (Bohemia, Moravia, small part of Silesia) and on former Hungarian territory (Slovakia and Ruthenia): 3 lands [země] (also called district units [obvody]) Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia + 21 counties [župy] in today's Slovakia + 2? counties in today's Ruthenia; both lands and counties were divided in districts [okresy]

- 1923–1927: like above, except that the above counties were replaced by 6 (grand) counties [(veľ)župy] in today's Slovakia and 1 (grand) county in today's Ruthenia, and the number and frontiers of the okresy were changed on these 2 territories

- 1928–1938: 4 lands [in Czech: země / in Slovak: krajiny]: Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia; divided in districts [okresy]

- late 1938–March 1939: like above, but Slovakia and Ruthenia were promoted to "autonomous lands"

- 1945–1948: like 1928–1938, except that Ruthenia became part of the Soviet Union

- 1949–1960: 19 regions [kraje] divided in 270 districts [okresy]

- 1960–1992: 10 regions [kraje], Prague, and (since 1970) Bratislava; divided in 109–114 districts (okresy]); the kraje were abolished temporarily in Slovakia in 1969–1970 and for many functions since 1991 in Czechoslovakia; in addition, the two republics Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic were established in 1969 (without the word Socialist since 1990)

Politics

GOTTWALD, HUSAK, DUBCEK

After WWII, monopoly on politics held by Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Gustáv Husák elected first secretary of KSC in 1969 (changed to general secretary in 1971) and president of Czechoslovakia in 1975. Other parties and organizations existed but functioned in subordinate roles to KSC. All political parties, as well as numerous mass organizations, grouped under umbrella of the National Front. Human rights activists and religious activists severely repressed.

Constitutional development

Czechoslovakia had the following constitutions throughout its history (1918 – 1992):

- Temporary Constitution of November 14 1918 [democratic], see: Czechoslovakia: 1918 - 1938

- The 1920 Constitution (The Constitutional Document of the Czechoslovak Republic) [democratic, in force till 1948, several amendments], see: Czechoslovakia: 1918 - 1938

- The Communist 1948 Ninth-of-May Constitution

- The Communist 1960 Constitution of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic with major amendments in 1968 (Constitutional Law of Federation), 1971, 1975, 1978, and in 1989 (at which point the leading role of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia was abolished). It was amended several more times during 1990-1992 (e. g. 1990, name change to Czecho-Slovakia, 1991 incorporation of the human rights charter)

Economy

After WWII, economy centrally planned with command links controlled by communist party, similar to Soviet Union. Large metallurgical industry but dependent on imports for iron and nonferrous ores.

- Industry: Extractive and manufacturing industries dominated sector. Major branches included machinery, chemicals, food processing, metallurgy, and textiles. Industry wasteful of energy, materials, and labor and slow to upgrade technology, but country source of high-quality machinery and arms for other communist countries.

- Agriculture: Minor sector but supplied bulk of food needs. Dependent on large imports of grains (mainly for livestock feed) in years of adverse weather. Meat production constrained by shortage of feed, but high per capita consumption of meat.

- Foreign Trade: Exports estimated at US$17.8 billion in 1985, of which 55 % machinery, 14 % fuels and materials, 16 % manufactured consumer goods. Imports at estimated US$17.9 billion in 1985, of which 41 % fuels and materials, 33 % machinery, 12 % agricultural and forestry products other. In 1986, about 80 % of foreign trade with communist countries.

- Exchange Rate: Official, or commercial, rate Kcs 5.4 per US$1 in 1987; tourist, or noncommercial, rate Kcs 10.5 per US$1. Neither rate reflected purchasing power. The exchange rate on the black market was around Kcs 30 per US$1, and this rate became the official one once the currency became convertible in the early 1990s.

- Fiscal Year: Calendar year.

- Fiscal Policy: State almost exclusive owner of means of production. Revenues from state enterprises primary source of revenues followed by turnover tax. Large budget expenditures on social programs, subsidies, and investments. Budget usually balanced or small surplus.

After WWII, country energy short, relying on imported crude oil and natural gas from Soviet Union, domestic brown coal, and nuclear and hydroelectric energy. Energy constraints a major factor in 1980s.

Population and ethnic groups

Czechoslovakia's ethnic composition in 1987 offered a stark contrast to that of the First Republic (see History). The Sudeten Germans that made up the majority of the population in border regions were forcibly expelled after World War II, and Carpatho-Ukraine (poor and overwhelmingly Ukrainian and Hungarian) had been ceded to the Soviet Union following World War II. Czechs and Slovaks, about two-thirds of the First Republic's population in 1930, represented about 94 % of the population by 1950.

The aspirations of ethnic minorities had been the pivot of the First Republic's politics. This was no longer the case in the 1980s. Nevertheless, ethnicity continued to be a pervasive issue and an integral part of Czechoslovak life. Although the country's ethnic composition had been simplified, the division between Czechs and Slovaks remained; each group had a distinct history and divergent aspirations.

From 1950 through 1983, the Slovak share of the total population increased steadily. The Czech population as a portion of the total declined by about 4 %, while the Slovak population increased by slightly more than that. The actual numbers did not imperil a Czech majority; in 1983 there were still more than two Czechs for every Slovak. In the mid-1980s, the respective fertility rates were fairly close, but the Slovak fertility rate was declining more slowly.

From creation to dissolution — overview

|

Czechoslovakia (or Czecho-Slovakia) | 1918 - 1939; 1945 - 1992 |

|||||||

|

Austria-Hungary (Bohemia, Moravia, a part of Silesia, northern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary (Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia) |

Czechoslovak Republic |

Sudetenland + other German territories "Upper Hungary" territories of Hungary |

Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR) |

Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR) |

Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (ČSFR) |

Czech Republic Slovakia |

|

|

Czecho-Slovak Republic (ČSR) incl. autonomous Slovakia and Transcarpathian Ukraine (1938-1939) |

Protectorate WWII Slovak Republic |

||||||

|

(further) "Upper Hungary" of Hungary |

part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic |

Zakarpattia Oblast of Ukraine |

|||||

|

German occupation |

Communist era |

||||||

|

govern. in exile |

|||||||

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Playing the blame game, Prague Post, July 6th, 2005

- ↑ http://www.law.nyu.edu/eecr/vol11num1_2/special/rupnik.html

External links

- Orders and Medals of Czechoslovakia including Order of the White Lion (in English and Czech)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.