Vikramāditya

- For the Gupta king, see Chandragupta II Vikramāditya

| Vikramaditya's capital, Ujjain Vikramaditya's Capital • India | |

| Coordinates: | |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+5:30) |

| Area • Elevation |

• 491 m (1,611 ft) |

| District(s) | Ujjain |

| Population | 429,933 (2001) |

Coordinates:

The name king Vikramaditya (Sanskrit: विक्रमादित्य) is a Sanskrit tatpurusha, from विक्रम (vikrama) meaning "valour" and आदित्य Āditya, son of Aditi. One of the most famous sons of Aditi, or adityas, was Surya the sun god; hence, Vikramaditya means Surya, translating to "Sun of valor." He is also called Vikrama or Vikramarka (Sanskrit arka meaning the Sun).

Originally, the title Vikramaditya had been bestowed upon a legendary king of Ujjain, India, famed for his wisdom, valor and magnanimity. He assembled a cadre of scholars, "nava-ratna" or the "Nine Gems," whose work ushered a golden age in Sanskrit scholarship. The Nine Gems included Dhanwanthari, Kshapanaka, Amarasimha, Shankhu, Khatakarpara, Kalidasa, Vetalbhatt (or Vetalabhatta), Vararuchi, and Varahamihira. the Hindu tradition in India and Nepal holds that the widely used ancient calendar of the Vikrama Samvat or Vikrama's era had been created by the legendary king following his victory over the Sakas in 56 B.C.E.

The title "Vikramaditya" has also been assumed by many kings in Indian history. Other notables who has assumed the title include the Gupta King Chandragupta II and Samrat Hem Chandra Vikramaditya (popularly known as "Hemu").

Legend of Vikramaditya

The legendary Vikramaditya is a popular figure in both Sanskrit and regional languages in India. Vikramaditya may have lived in the first century B.C.E. and may have been defeated by the King Shalivahana. According to the Katha-sarita-sagara[1] account, written in the twelfth century C.E., he had been the son of Ujjain's King Mahendraditya of the Paramara dynasty. According to other sources, Vikramaditya also has been recorded as an ancestor of the Tuar dynasty of Delhi.[2][3][4][5][6]

His name has been freely associated with events and monuments of unknown origin, giving birth to a complex of legendary tales attributed to him. Sir Richard Burton, who first translated the tales of Vikramaditya into English, called him, "the King Arthur of the East."[7] The two most famous tales in Sanskrit—Vetala Panchvimshati or Baital Pachisi ("The 25 tales of the Vampire") and Simhasana-Dwatrimshika ("The 32 tales of the throne)" also known as Sinhasan Batteesee)—have been found in a variety of Sanskrit version as well as in regional languages.

The tales of the vampire (Vetala) contains twenty-five legends in which the king tries to capture and hold on to a vampire who tells a puzzling tale, ending it with a question for the king. If the king speaks, the vampire will fly away, denying the opportunity to seize and capture him. The king can be quiet only if he does not know the answer, otherwise his head would burst open. The king, being extremely wise, discovers that he knows the answer to every question. So the game of catching the vampire and letting it escape continued twenty four times until the last question puzzles even Vikramaditya. A version of those tales exist in the Katha-Saritsagara.

The tales of the throne link to the lost throne of Vikramaditya which king Bhoja, the Paramara king of Dhar, found after many centuries. Dhar become famous as well with a number of tales relating stories of how he attempted to sit on the throne. Thirty two female statues which adorn that throne challenge him to ascend the throne only if he has magnanimity equal to Vikramaditya as revealed by a tale she would narrate. That led to thirty two attempts (and thirty two tales) to claim the throne Vikramaditya, in each case Bhoja acknowledged his inferiority. Finally, the statues let him ascend the throne, pleased with his humility.

Nine Gems and Vikramaditya's court in Ujjain

Indian tradition claims that Dhanwanthari, Kshapanaka, Amarasimha, Shankhu, Khatakarpara, Kalidasa, Vetalbhatt (or Vetalabhatta), Vararuchi, and Varahamihira were a part of Vikramaditya's court in Ujjain. The king commissioned nine men of letters, called the "nava-ratna" (literally, Nine Gems), to work in his court. Kalidasa had been the legendary Sanskrit laureate. Varahmihira had been a soothsayer of renown in his era, predicting the death of Vikramaditya’s son. Vetalbhatt had been a Maga Brahmin known for writing work of the sixteen stanza "Niti-pradeepa" (Niti-pradīpa, literally, the lamp of conduct) in tribute to Vikramaditya.

The Jain monk account

The traditional Indian dating, using a calendar believed to have been established by Vikramaditya, makes him a first century B.C.E. king. The chronology for generally accepted Indian kings and dynasties does not place any Vikramaditya in that period.

Kalakacharya Kathanaka, a work by Mahesara Suri, a Jain sage around the twelfth century C.E. may be the source of Vikramaditya's dates. The Kathanaka (meaning, "an account") tells the story of a famed Jain monk Kalakacharya. It mentions that Gardabhilla, the then powerful king of Ujjain, abducted a nun named Sarasvati, the sister of the monk. The enraged monk sought help of the Saka ruler, a Shahi, in Sakasthana. Heavily outnumbered, the Saka king defeated Gardabhilla with the aid of miracles, making him a captive. Sarasvati was repatriated. Gardabhilla was forgiven though. The defeated king retired to the forest where a tiger killed him. His son, Vikramaditya, raised in the forest, had to rule from Pratishthana (in modern Maharashtra). Later, Vikramaditya invaded Ujjain and drove away the Sakas. To commemorate that event he started a new era called the Vikrama Samvat.

Recent interpretations of the legend

Western historians in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have made an association of Vikramaditya with the legendary king with the great Gupta king Chandragupta II, but some Indian historians consider that association incorrect. Centuries had separated the eras of the two leaders; the Guptas appeared to have used the name "Vikramaditya" for titular effect. The popularity of Vikramaditya and the two sets of popular folk stories about his life has given rise to the increasingly common naming of Hindu children by the name Vikram.

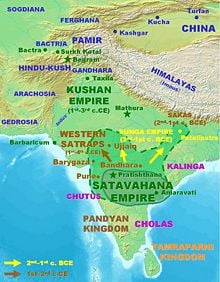

Vikramaditya and Shalivahana era

Legend has it that the Satavahana King, Shalivahana defeated Vikramaditya and captured Ujjain in the first century C.E. Shalivahana inaugurated the Shalivahana era seventy eight C.E., retaining his capital in Pratisthana. The account of the battle had been recorded in "Katha-Saritsagara." Shalivahana is a legendary figure in Indian history, the king usually identified with the Satavahana king Gautamiputra Satkarni. The Satavahanas ruled the region beginning in the third century B.C.E., long before the Guptas from Pratisthana conquered the region.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Samskrutam, Katha Sarita Sagara. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ↑ James Prinsep, Edward Thomas, and Henry Thoby Prinsep, Essays on Indian Antiquities, Historic, Numismatic, and Palæographic, of the Late James Prinsep, to Which are Added his Useful Tables, Illustrative of Indian History, Chronology, Modern Coinages, Weights, Measures, etc (London: J. Murray, 1858), 250.

- ↑ M. S. Nateson, Pre-Mussalman India: A History of the Motherland Prior to the Sultanate of Delhi (New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 2000), 131.

- ↑ Edward Balfour, The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia: Commercial, Industrial and Scientific, Products of the Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures (London: B. Quaritch, 1885), 502.

- ↑ James Tod and William Crooke, Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, or The Central and Western Rajput States of India (London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1920), 912.

- ↑ Prinsep, Indian Antiquities, 157.

- ↑ Sacred Texts, Sir Richard R. Burton, Vikram and The Vampire, Preface to The First (1870) Edition. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Asiatic Society of Bombay, O.P. Kejariwal, Suresh K. Sharma, and Shashi Anand. 2004. Journal of the Asiatic Sociey of Bombay: A Comprehensive Index, 1841-2001. New Delhi: Nehru Memorial Museum and Library & Asiatic Society of Mumbai. ISBN 9788187614234.

- Balfour, Edward. 1885. The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia: Commercial, Industrial and Scientific, Products of the Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures. London: B. Quaritch. OCLC 3257764.

- Burton, Richard F., Ernest Henry Griset, and wood engraver Dalziel. 1870. Vikram and the Vampire. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. OCLC 177742965.

- Edgerton, Franklin. 1926. Vikrama's Adventures; or, The Thirty-Two Tales of the Throne, a Collection of Stories About King Vikrama, as Told by the Thirty-Two Statuettes That Supported his Throne, Edited in Four Different Recensions of the Sanskrit Original (Vikrama-charita or Sinhasana-dvatrinçaka). Harvard oriental series, v. 26-27. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 255821.

- Nateson, M.S. 2000. Pre-Mussalman India: A History of the Motherland Prior to the Sultanate of Delhi. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120615298.

- Prinsep, James, Edward Thomas, and Henry Thoby Prinsep. 1858. Essays on Indian Antiquities, Historic, Numismatic, and Palæographic, of the late James Prinsep, to Which are Added his Useful Tables, Illustrative of Indian History, Chronology, Modern Coinages, Weights, Measures, etc. London: J. Murray. OCLC 5574640.

- Tawney, Charles Henry, and Somadeva. 1880. The Kathá Sarit Ságara or Ocean of the Streams of Story. Calcutta: Thomas, Baptist Mission Press. OCLC 61964843.

- Tod, James, and William Crooke. 1920. Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, or the Central and Western Rajput States of India. London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press. OCLC 4053976.

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Story of Vikramaditya re-building Ayodhya Temple

- Collection of Stories showing greatness of Vikramaaditya: Audaaryam, Paropakaara Buddhi, Vitarana Buddhi, Daana Gunam, Vikramaaditaya

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.