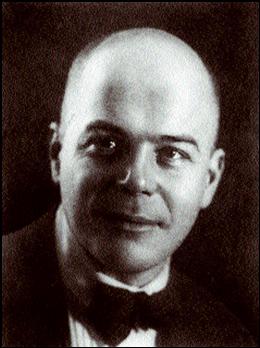

| Viktor Shklovsky | |

|---|---|

Victor Borisovich Shklovsky | |

| Born | January 24, [O.S. 12 January] 1893 Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | December 6 1984 (aged 91) Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Occupation | Literary theorist, critic, writer |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Literary movement | Russian Formalism |

Viktor Borisovich Shklovsky[1] (Russian: Ви́ктор Бори́сович Шкло́вский, Russian pronunciation: [ˈʂklofskʲɪj]; January 24, [O.S. January 12] 1893 – December 6, 1984) was a Russian and Soviet literary theorist, critic, writer, and pamphleteer. In his early career, he founded a significant society for the study of poetic language.

Later he became one of the major figures associated with the development of Russian Formalism, which fundamentally changed how literary criticism worked. As the name implies, Formalism focused not on what the content of the story was, but rather on how it was told. His contributions to Formalist ideas, like "Art as Technique" and the narrative distinction between the "fabula" and the "sjuzhet," gave critics a new vocabulary to analyze literary works.

Life

Viktor Shklovsky was born in St. Petersburg, Russia. His father was a Lithuanian Jewish mathematician (with ancestors from Shklov) who converted to Russian Orthodoxy. His mother was of German-Russian origin. He attended St. Petersburg University.

During the First World War, he volunteered for the Russian Army, eventually becoming a driving trainer in an armored car unit in St. Petersburg. While in St. Petersburg, he founded OPOYAZ (Obshchestvo izucheniya POeticheskogo YAZyka—Society for the Study of Poetic Language), OPOJAZ (ОПОЯЗ) (Russian: Общество изучения Поэтического Языка, Obščestvo izučenija POètičeskogo JAZyka, "Society for the Study of Poetic Language"). OPOJAZ was a prominent group of linguists and literary critics in St. Petersburg founded in 1916 and dissolved by the early 1930s. The group included not only Shklovsky, but also other prominent members of the Russian formalist school, including literary critics like Boris Eikhenbaum, Osip Brik, Boris Kušner , and Yury Tynianov.

Shklovsky participated in the February Revolution of 1917. Subsequently, the Russian Provisional Government sent him as an assistant Commissar to the Southwestern Front where he was wounded and got an award for bravery. After that he was an assistant Commissar of the Russian Expeditionary Corps in Persia (see Persian Campaign).

Shklovsky returned to St. Petersburg in early 1918, after the October Revolution. During the beginning of the Russian Civil War he opposed Bolshevism and took part in an anti-Bolshevik plot organized by members of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party. After the conspiracy was discovered by the Cheka, Shklovsky went into hiding, traveling in Russia and the Ukraine, but was eventually pardoned in 1919 due to his connections with Maxim Gorky. After his experience he decided to abstain from political activity. His siblings did not escape the turmoil of the revolution. They were executed by the Soviet regime (one in 1918, the other in 1937) and his sister died from hunger in St. Petersburg in 1919.

After his pardon, Shklovsky integrated into Soviet society and even took part in the Russian Civil War, serving in the Red Army. However, in 1922, he had to go into hiding once again, as he was threatened with arrest and possible execution for his former political activities. He fled via Finland to Germany. In Berlin, in 1923, he published his memoirs about the period 1917–22 under the title Сентиментальное путешествие, воспоминания (Sentimental'noe puteshestvie, vospominaniia, A Sentimental Journey), an allusion to A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy by Laurence Sterne, an author he much admired and whose digressive style had a powerful influence on Shklovsky's writing. In the same year he was allowed to return to the Soviet Union, after he included an appeal to Soviet authorities in the last pages of his epistolary novel Zoo, or Letters Not About Love.

Writer and theorist

The OPOJAZ (the Society for the Study of Poetic Language) group headed by Shklovsky was primarily concerned with the formal method and focused on technique and device: "Literary works, according to this model, resemble machines: they are the result of an intentional human activity in which a specific skill transforms raw material into a complex mechanism suitable for a particular purpose."[2] This approach strips the literary artifact from its connection with the author, reader, and historical background. Along with the Moscow linguistic circle it was responsible for the development of Russian Formalism and literary semiotics. The group was dissolved under political pressure as "formalism" came to be a political term of opprobrium in the Soviet state.

Defamiliarization

Shklovsky is perhaps best known for developing the concept of ostranenie or defamiliarization (also translated as "estrangement") in literature.[3] He explained the concept in 1917 in the important essay "Art as Technique" (also translated as "Art as Device")[4] which comprised the first chapter of his seminal Theory of Prose, first published in 1925. He argued for the need to turn something that has become over-familiar, like a cliché in the literary canon, into something revitalized:[5]

And so, in order to return sensation to our limbs, in order to make us feel objects, to make a stone feel stony, man has been given the tool of art. The purpose of art, then, is to lead us to a knowledge of a thing through the organ of sight instead of recognition. By "enstranging" objects and complicating form, the device of art makes perception long and "laborious." The perceptual process in art has a purpose all its own and ought to be extended to the fullest. Art is a means of experiencing the process of creativity. The artifact itself is quite unimportant.[6]

Nineteenth century Russian literary criticism was heavily influenced by Vissarion Belinsky's dictum that "Art is thinking in images." In the essay Shklovsky argues that such a shopworn understanding fails to address the major feature of art, which is not to be found in its content but its form. One of Shklovsky's major contentions was that poetic language is fundamentally different than the language that we use everyday. “Poetic speech is framed speech. Prose is ordinary speech–economical, easy, proper, the goddess of prose [dea prosae] is a goddess of the accurate, facile type, of the 'direct' expression of a child.”[6] What makes art is not the "image," or the idea, which can easily be expressed in prosaic form just as well as in poetic form. This difference is the manipulation of form, or the artist's technique, which is the key to the creation of art.

The image can be given a prosaic presentation but it is not art because the form is not interesting, it is automatic. This automatic use of language, or “over-automatization” as Shklovsky refers to it, causes the idea or meaning to “function as though by formula.” [6] This distinction between artistic language and everyday language, is the distinguishing characteristic of all art. He invented the term defamiliarization to “distinguish poetic from practical language on the basis of the former’s perceptibility.”[7]

Formalism

Shklovsky also contributed the plot/story distinction (syuzhet/fabula), which separates out the sequence of events the work relates (the plot) from the sequence in which those events are presented in the work (the story). In narratology, fabula (Russian: фабула, Russian pronunciation: [ˈfabʊlə]) equates to the thematic content of a narrative and syuzhet[8] (Russian: сюжет, Russian pronunciation: [sʲʊˈʐɛt]) equates to the chronological structure of the events within the narrative. Shklovsky and Vladimir Propp originated the terminology as part of the Russian Formalism movement in the early twentieth century.[9][10] Narratologists have described fabula as "the raw material of a story", and syuzhet as "the way a story is organized."[11]

Other works

In addition to literary criticism and biographies about such authors as Laurence Sterne, Maxim Gorky, Leo Tolstoy, and Vladimir Mayakovsky, he wrote a number of semi-autobiographical works disguised as fiction, which also served as experiments in developing theories of literature.

Film

Shklovsky was one of the very early serious writers on film.[12] A collection of his essays and articles on film was published in 1923 (Literature and Cinematography, first English edition 2008). He was a close friend of director Sergei Eisenstein and published an extensive critical assessment of his life and works (Moscow 1976, no English translation).

Beginning in the 1920s and well into the 1970s Shklovsky worked as a screenwriter on numerous Soviet films (see Select Filmography below), a part of his life and work that, thus far, has received very limited attention. In his book Third Factory Shklovsky reflects on his work in film, writing: "First of all, I have a job at the third factory of Goskino (acronym for State film). Second of all, the name isn't hard to explain. The first factory was my family and school. The second was Opoyaz. And the third – is processing me at this very moment."[13]

Later life and death

The Yugoslav scholar Mihajlo Mihajlov visited Shklovsky in 1963 and wrote: "I was much impressed by Shklovsky's liveliness of spirit, his varied interests and his enormous culture. When we said goodbye to Viktor Borisovich and started for Moscow, I felt that I had met one of the most cultured, most intelligent and best-educated men of our century."[14]

He died in Moscow in 1984.

Legacy

Viktor Shklovsky's Theory of Prose was published in 1925.[6] Shklovsky himself is still praised as "one of the most important literary and cultural theorists of the twentieth century"[15] (Modern Language Association Prize Committee); "one of the most lively and irreverent minds of the last century"[16] (David Bellos); "one of the most fascinating figures of Russian cultural life in the twentieth century"[16] (Tzvetan Todorov)

Shklovsky's work pushes Russian Formalism towards understanding literary activity as integral parts of social practice, an idea that becomes important in the work of Mikhail Bakhtin and Russian and Prague School scholars of semiotics. Shklovsky's thought also influenced western thinkers, partly due to Tzvetan Todorov's translations of the works of Russian formalists in the 1960s and 1970s, including not only Tzvetan Todorov, but Gerard Genette and Hans Robert Jauss.

Bibliography (English)

- A Sentimental Journey: Memoirs, 1917–1922 (1923, translated in 1970 by Richard Sheldon)

- Zoo, or Letters Not About Love (1923, translated in 1971 by Richard Sheldon) – epistolary novel

- Knight's Move (1923, translated in 2005) – collection of essays first published in the Soviet theatre journal, The Life of Art

- Literature and Cinematography (1923, translated in 2008)

- Theory of Prose (1925, translated in 1990) – essay collection

- Third Factory (1926, translated in 1979 by Richard Sheldon)

- The Hamburg Score (1928, translation by Shushan Avagyan published in 2017)

- Life of a Bishop's Assistant (1931, translation by Valeriya Yermishova published in 2017)

- A Hunt for Optimism (1931, translated in 2012)

- Mayakovsky and his circle (1941, translated in 1972) – about the times of poet Vladimir Mayakovsky

- Leo Tolstoy (1963, translated in 1996)

- Bowstring: On the Dissimilarity of the Similar (1970, translated in 2011)

- Energy of Delusion: A Book on Plot (1981, translated in 2007)

Select filmography (as writer)

- By the Law, 1926, director Lev Kuleshov, based on a story by Jack London

- Jews on Land, 1927, director Abram Room

- Bed and Sofa, 1927, director Abram Room

- The House on Trubnaya, 1928, director Boris Barnet

- The House of Ice, 1928, director Konstantin Eggert, based on the eponymous novel by Ivan Lazhechnikov

- Krazana, 1928, director Kote Mardjanishvili, based on the novel The Gadfly by Ethel Lilian Voynich

- Turksib, documentary, 1929, director Viktor Alexandrovitsh Turin

- Amerikanka (film), 1930, director Leo Esakya[17]

- The Horizon, 1932, director Lev Kuleshov

- Minin and Pozharsky, 1939, director Vsevolod Pudovkin

- The Gadfly, 1956, director Aleksandr Faintsimmer, based on the eponymous novel by Ethel Lilian Voynich

- Kazaki, 1961, director Vasili Pronin

Interviews

- Serena Vitale: Shklovsky: Witness to an Era, translated by Jamie Richards, Dalkey Archive Press, Champaign, IL, London, U.K., Dublin, IR: 2012, ISBN 978-1564787910 (Italian edition first pub. in 1979). The interview by Vitale is arguably the most important historical document covering the later years of Shklovsy’s life and work.[18]

Notes

- ↑ Also transliterated Shklovskii.

- ↑ Peter Steiner, Russian Formalism: A Metapoetics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984, ISBN 9780801493669), 18.

- ↑ Carla Benedetti, The empty cage: inquiry into the mysterious disappearance of the author (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0801441455), 118. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ↑ Viktor Shklovsky, "Art as Technique," in Theory of Prose trans. Benjamin Sher (Funks Grove, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1990, ISBN 0916583643), 1-14.

- ↑ Peter Brooker, Andrzej Gasiorek, et. al., The Oxford Handbook of Modernism (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0198778448), 841. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Viktor Shklovsky, Theory of Prose trans. Benjamin Sher, (Funks Grove, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1990, ISBN 0916583643), 6, 16, 20.

- ↑ Lawrence Crawford, “Victor Shklovskij: Différance in Defamiliarization,” Comparative Literature 36 (1984): 209.

- ↑ Also romanized as sjuzhet, sujet, sjužet, siuzhet or suzet.

- ↑ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0292792494).

- ↑ Viktor Shklovsky, Literature and Cinematography (Funks Grove, IL: Dalkey Archive Press , 2008, ISBN 978-1564784827).

- ↑ Paul Cobley, "Narratology," in The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism, 2nd. ed., Michael Groden, et. al., eds., (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0801880100).

- ↑ Peter Rollberg, Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016, ISBN 978-1442268425), 670–671.

- ↑ Viktor Shklovsky, Third Factory (Funks Grove, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 2002, ISBN 1564783170), 8–9.

- ↑ Mihajlo Mihajlov, Moscow Summer (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1965), 104.

- ↑ "Announcing MLA award winners: Ecocriticism and Italy and Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader," Bloomsbury Literary Studies Blog, December 11, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Viktor Shklovsky, Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader (London, U.K.: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016, ISBN 978-1501310379). Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ↑ Antti Alanen, Amerikanka (American Woman): Film Diary. October 3, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ↑ Norbert Francis, The Motherland will Notice her Terrible Mistake: Paradox of Futurism in Jasienski, Mayakovsky and Shklovsky. academia.com, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benedetti, Carla. The Empty Cage: inquiry into the mysterious disappearance of the author. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0801441455

- Brooker, Peter, Andrzej Gasiorek, et. al. The Oxford Handbook of Modernism. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0198778448

- Groden, Michael, Martin Kreiswirth, and Imre Szeman (eds.). The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism, 2nd. edition. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0801880100

- Mihajlov, Mihajlo. Moscow Summer. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1965.

- Propp, Vladimir. Morphology of the Folktale. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2010 (original 1929). ISBN 978-0292792494

- Rollberg, Peter. Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016. ISBN 978-1442268425

- Shklovsky, Viktor. "Art as Technique," in Theory of Prose translated by Benjamin Sher. Funks Grove, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1990. ISBN 0916583643

- Shklovsky, Viktor. Third Factory. Funks Grove, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 2002. ISBN 1564783170

- Shklovsky, Viktor. Literature and Cinematography. Funks Grove, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 2008 (original 1923). ISBN 978-1564784827

- Shklovsky, Viktor. Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader. London, U.K.: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016. ISBN 978-1501310379

- Steiner, Peter. Russian Formalism: A Metapoetics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0801493669

External links

All links retrieved August 22, 2023

- An excerpt from Bowstring in Asymptote

- The Formalist’s Formalist: On Viktor Shklovsky by Joshua Cohen

- Biography in "Энциклопедия Кругосвет" (in Russian)

- Shklovsky's "Monument to a Scientific Error", translation available online at David Bordwell's site.

- The Trotsky-Shklovsky Debate: Formalism versus Marxism. International Journal of Russian Studies 6 (January 2017): 15–27.

- Victor Shklovsky and Roman Jacobson. Life as a Novel documentary film by Vladimir Nepevny

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.