| Names | |

|---|---|

| Chinese: | æç« |

| Pinyin: | DĂč FÇ |

| Wade-Giles: | Tu⎠Fu³ |

| Chinese courtesy name: | ZÇmÄi ćçŸ |

| Also known as: | DĂč ShĂ olĂng æć°é” DĂč GĆngbĂč æć·„éš ShĂ olĂng YÄlÇo ć°é”éè |

| |

Du Fu (712â770 C.E.) was a prominent Chinese poet of the Tang Dynasty. Along with Li Bai (Li Bo), he is frequently called the greatest of the Chinese poets. While Li Bai is often associated with the religion of Daoism, Du Fu is considered to be very closely connected to Confucianism, with some critics seeing his poetry as the apotheosis of Confucian art and thought.

Certainly, Du Fu was much more down-to-earth in comparison with Li Bai's wandering restlessness. His poetry shows a concern for civil society, and for the lives of the underprivileged, that marks Du Fu as one of the most humane and moral of Chinese poets; and indeed, Du Fu's sense of moralityâand his ability to communicate it beautifully through his poemsâare the qualities for which he has been praised for centuries by Chinese scholars and poets. The Chinese often refer to him as "The Poet-Historian" and "The Poet-Sage," and Du Fu has often drawn comparisons to the sagacious, didactic poets of the ancient world of the West, such as Horace and Ovid. Comparisons, however, are difficult to make, simply because Du Fu occupies such a preeminent position in the history of Chinese literature. He revolutionized the form and the tone of Chinese poetry, and in particular he demonstrated the possibilities of lÇshi, or formal verse, transforming an incredibly difficult style of poetry that had previously been used primarily as an exercise into a platform for high art.

Life

Traditionally, Chinese literary criticism has placed great emphasis on knowledge of the life of the author when interpreting a work, a practice which Watson attributes to "the close links that traditional Chinese thought posits between art and morality" (xvii). This becomes all the more important in the case of a writer such as Du Fu, in whose poems morality and history are such prominent themes. Another reason, identified by the Chinese historian William Hung, is that Chinese poems are typically extremely concise, omitting circumstantial factors which may be relevant, but which could be reconstructed by an informed contemporary. For modern, Western readers, therefore, "The less accurately we know the time, the place and the circumstances in the background, the more liable we are to imagine it incorrectly, and the result will be that we either misunderstand the poem or fail to understand it altogether" (5). Du Fu's life is therefore treated here in some detail.

Early years

Most of what is known of Du Fuâs life comes from his own poems. Like many other Chinese poets, he came from a noble family which had fallen into relative poverty. He was born in 712 C.E.; the birthplace is unknown, except that it was near Luoyang, Henan province. In later life he considered himself to belong to the capital city of Chang'an.

Du Fu's mother died shortly after he was born, and he was partially raised by his aunt. He had an elder brother, who died young. He also had three half brothers and one half-sister, to whom he frequently refers in his poems, although he never mentions his stepmother.

As the son of a minor scholar-official, his youth was spent on the standard education of a future civil servant: study and memorization of the Confucian classics of philosophy, history and poetry. He later claimed to have produced creditable poems by his early teens, but these have been lost.

In the early 730s, he traveled in the Jiangsu/Zhejiang area; his earliest surviving poem, describing a poetry contest, is thought to date from the end of this period, around 735. In that year he traveled to Chang'an to take the civil service exam, but was unsuccessful. Hung concludes that he probably failed because his prose style at the time was too dense and obscure, while Chou suggests that his failure to cultivate connections in the capital may have been to blame. After this failure he went back to traveling, this time around Shandong and Hebei.

His father died around 740. Du Fu would have been allowed to enter the civil service because of his father's rank, but he is thought to have given up the privilege in favor of one of his half brothers. He spent the next four years living in the Luoyang area, fulfilling his duties in domestic affairs.

In the autumn of 744 he met Li Bai (Li Bo) for the first time, and the two poets formed a somewhat one-sided friendship: Du Fu was by some years the younger, while Li Bai was already a poetic star. There are twelve poems to or about Li Bai from the younger poet, but only one in the other direction. They met again only once, in 745.

In 746 he moved to the capital in an attempt to resurrect his official career. He participated in a second exam the following year, but all the candidates were failed by the prime minister. Thereafter, he never again attempted the examinations, instead petitioning the emperor directly in 751, 754 and probably again in 755. He married around 752, and by 757 the couple had five childrenâthree sons and two daughtersâbut one of the sons died in infancy in 755. From 754 he began to have lung problems, the first of a series of ailments which dogged him for the rest of his life.

In 755 he finally received an appointment to civil service as registrar of the Right Commandant's office of the Crown Prince's Palace. Although this was a minor post, in normal times it would have been at least the start of an official career. Even before he had begun work, however, the position was swept away by events.

War

The An Lushan Rebellion began in December 755, and was not completely crushed for almost eight years. It caused enormous disruption to Chinese society: the census of 754 recorded 52.9 million people, but that of 764 just 16.9 million, the remainder having been killed or displaced.

During this chaotic time, Du Fu led a largely itinerant life, forced to move by wars, famines, and the commandment of the emperor. This period of unhappiness, however, was the making of Du Fu as a poet. Eva Shan Chou has written, "What he saw around himâ the lives of his family, neighbors, and strangersâ what he heard, and what he hoped for or feared from the progress of various campaignsâ these became the enduring themes of his poetry" (Chou, 62). Certainly it was only after the An Lushan Rebellion that Du Fu truly discovered his voice as a poet.

In 756 Emperor Xuanzong was forced to flee the capital and abdicate. Du Fu, who had been away from the city, took his family to a place of safety and attempted to join up with the court of the new emperor, but he was captured by the rebels and taken to Changâan. Around this time Du Fu is thought to have contracted malaria.

He escaped from Chang'an the following year, and was appointed to a new post in the civil service when he rejoined the court in May 757. This post gave access to the emperor, but was largely ceremonial. Du Fu's conscientiousness compelled him to try to make use of it; he soon caused trouble for himself by protesting against the removal of his friend and patron, Fang Guan, on a petty charge; he was then himself arrested, but was pardoned in June. He was granted leave to visit his family in September, but he soon rejoined the court and on December 8, 757, he returned to Changâan with the emperor following its recapture by government forces. However, his advice continued to be unappreciated, and in the summer of 758 he was demoted to a post as commissioner of education in Huazhou. The position was not to his taste. In one poem, he wrote: "I am about to scream madly in the office / Especially when they bring more papers to pile higher on my desk."

He moved on again in the summer of 759; this has traditionally been ascribed to famine, but Hung believes that frustration is a more likely reason. He next spent around six weeks in Qinzhou, where he wrote over sixty poems.

Chengdu

In 760 he arrived in Chengdu, where he based himself for most of the next five years. By the autumn of that year he was in financial trouble, and sent poems begging help to various acquaintances. He was relieved by Yen Wu, a friend and former colleague who was appointed governor general at Chengdu. Despite his financial problems, this was one of the happiest and most peaceful periods of his life, and many of his poems from this period are peaceful depictions of his life in his famous "thatched hut."

Last years

Luoyang, the region of his birthplace, was recovered by government forces in the winter of 762, and in the spring of 765 Du Fu and his family sailed down the Yangtze River, apparently with the intention of making their way back there. They traveled slowly, held up by Du Fu's ill-health. They stayed in Kuizhou at the entrance to the Three Gorges for almost two years from late spring 766. This period was Du Fu's last great poetic flowering, and here he wrote four hundred poems in his dense, late style.

In March 768 he began his journey again and got as far as Hunan province, where he died in Tanzhou in November or December 770, in his 59th year. He was survived by his wife and two sons, who remained in the area for some years at least.

Works

Criticism of Du Fu's works has focused on his strong sense of history, his moral engagement, and his technical excellence.

History

Since the Song Dynasty, Du Fu has been called by critics the "poet historian" (è©©ćČ shÄ« shÇ). The most directly historical of his poems are those commenting on military tactics or the successes and failures of the government, or the poems of advice which he wrote to the emperor. Indirectly, he wrote about the effect of the times in which he lived on himself, and on the ordinary people of China. As Watson notes, this is information "of a kind seldom found in the officially compiled histories of the era" (xvii).

Moral engagement

A second favorite epithet of Chinese critics is that of "poet sage" (è©©è shÄ« shĂšng), a counterpart to the philosophical sage, Confucius. One of the earliest surviving works, âThe Song of the Wagonsâ (from around 750 C.E.), gives voice to the sufferings of a conscript soldier in the imperial army, even before the beginning of the rebellion; this poem brings out the tension between the need of acceptance and fulfillment of one's duties, and a clear-sighted consciousness of the suffering which this can involve. These themes are continuously articulated in the poems on the lives of both soldiers and civilians which Du Fu produced throughout his life.

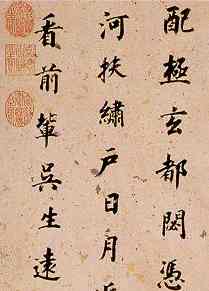

Du Fu's compassion for himself and for others was part of his general broadening of the scope of poetry: he devoted many works to topics which had previously been considered unsuitable for poetic treatment. Zhang Jie wrote that for Du Fu, "everything in this world is poetry" (Chou, 67), and he wrote extensively on subjects such as domestic life, calligraphy, paintings, animals and other poems.

Technical excellence

Du Fu's work is notable above all for its range. Chinese critics traditionally used the term jĂdĂ chĂ©ng (é性æ, "complete symphony"), a reference to Mencius' description of Confucius. Yuan Zhen was the first to note the breadth of Du Fu's achievement, writing in 813 that his predecessor, "united in his work traits which previous men had displayed only singly" (Chou, 42). He mastered all the forms of Chinese poetry: Chou says that in every form he "either made outstanding advances or contributed outstanding examples" (56). Furthermore, his poems use a wide range of registers, from the direct and colloquial to the allusive and self-consciously literary. The tenor of his work changed as he developed his style and adapted to his surroundings ("chameleon-like" according to Watson): his earliest works are in a relatively derivative, courtly style, but he came into his own in the years of the rebellion. Owen comments on the "grim simplicity" of the Qinzhou poems, which mirrors the desert landscape (425); the works from his Chengdu period are "light, often finely observed" (427); while the poems from the late Kuizhou period have a "density and power of vision" (433).

Although he wrote in all poetic forms, Du Fu is best known for his lÇshi, a type of poem with strict constraints on the form and content of the work. About two thirds of his 1,500 extant works are in this form, and he is generally considered to be its leading exponent. His best lÇshi use the parallelisms required by the form to add expressive content rather than as mere technical restrictions. Hawkes comments that, "it is amazing that Du Fu is able to use so immensely stylized a form in so natural a manner" (46).

Influence

In his lifetime, and immediately following his death, Du Fu was not greatly appreciated. In part this can be attributed to his stylistic and formal innovations, some of which are still "considered extremely daring and bizarre by Chinese critics" (Hawkes, 4). There are few contemporary references to himâonly eleven poems from six writersâand these describe him in terms of affection, but not as a paragon of poetic or moral ideals (Chou, 30). Du Fu is also poorly represented in contemporary anthologies of poetry.

However, as Hung notes, he "is the only Chinese poet whose influence grew with time" (1), and in the ninth century he began to increase in popularity. Early positive comments came from Bai Juyi, who praised the moral sentiments of some of Du Fu's works, and from Han Yu, who wrote a piece defending Du Fu and Li Bai on aesthetic grounds from attacks made against them.

It was in the eleventh century, during the Northern Song era, that Du Fu's reputation reached its peak. In this period a comprehensive reevaluation of earlier poets took place, in which Wang Wei, Li Bai and Du Fu came to be regarded as representing respectively the Buddhist, Daoist and Confucian strands of Chinese culture (Chou, 26). At the same time, the development of Neo-Confucianism ensured that Du Fu, as its poetic exemplar, occupied the paramount position (Ch'en, 265). Su Shi famously expressed this reasoning when he wrote that Du Fu was "preeminent... because... through all his vicissitudes, he never for the space of a meal forgot his sovereign" (quoted in Chou, 23). His influence was helped by his ability to reconcile apparent opposites: political conservatives were attracted by his loyalty to the established order, while political radicals embraced his concern for the poor. Literary conservatives could look to his technical mastery, while literary radicals were inspired by his innovations. Since the establishment of the People's Republic of China, Du Fu's loyalty to the state and concern for the poor have been interpreted as embryonic nationalism and socialism, and he has been praised for his use of simple, "people's language" (Chou, 66).

Translation

There have been a number of notable translations of Du Fuâs work into English. The translators have each had to contend with the same problems of bringing out the formal constraints of the original without sounding labored to the western ear (particularly when translating lÇshi), and of dealing with the allusions contained particularly in the later works (Hawkes writes, "his poems do not as a rule come through very well in translation," ix). One extreme on each issue is represented by Kenneth Rexrothâs One Hundred Poems from the Chinese. His are free translations, which seek to conceal the parallelisms through enjambment as well as expansion and contraction of the content; his responses to the allusions are firstly to omit most of these poems from his selection, and secondly to âtranslate outâ the references in those works which he does select.

An example of the opposite approach is Burton Watson's The Selected Poems of Du Fu. Watson follows the parallelisms quite strictly, persuading the western reader to adapt to the poems rather than vice versa. Similarly, he deals with the allusion of the later works by combining literal translation with extensive annotation.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ch'en Wen-hua. T'ang Sung tzu-liao k'ao.

- Chou, Eva Shan. (1995). Reconsidering Tu Fu: Literary Greatness and Cultural Context. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521440394

- Cooper, Arthur (trans.). (1986). Li Po and Tu Fu: Poems. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0140442723

- Hawkes, David. (1967). A Little Primer of Tu Fu. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9627255025

- Hung, William. (1952). Tu Fu: China's Greatest Poet. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0758143222

- Owen, Stephen (ed.). (1997). An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393971066

- Rexroth, Kenneth (trans.). (1971). One Hundred Poems from the Chinese. New Directions Press. ISBN 0811201815

- Watson, Burton (ed.). (1984). The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231056834

- Watson, Burton (trans.). (2002). The Selected Poems of Du Fu. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231128290

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2024.

- Du Fu Index â Chinese-Poems.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.