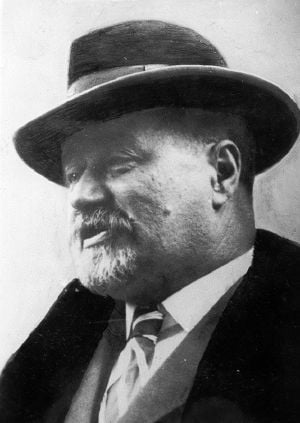

Stjepan Radić

Stjepan Radić (June 11, 1871 – August 8, 1928) was a Croatian politician and the founder of the Croatian Peasant Party (CPP, Hrvatska Seljačka Stranka) in 1905. His brother, Ante was also a founder. Radić is credited with galvanizing the peasantry of Croatia into a viable political force. Throughout his entire career, he was opposed to the union and, later, Serb hegemony in the first Yugoslavia and became an important political figure in that country serving as Minister of Education and leading his party to an electoral victory in 1928. While protracted debate took place on who and how a new government was to be formed, he was assassinated by a Serb politician in the Parliament itself, an act which even further alienated the Croats and the Serbs. His assassination turned him into a Croatian martyr in the cause of Croatia's national aspirations and desire for independence.

Radić opposed Croatia's union with Serbia, Bosnia and Slovenia in the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, arguing that this did not reflect the will of the people. For centuries Croatia had been divided between areas under the Ottoman Empire. To Croats, it seemed that the united nation was again being dominated by non-Croats. The new kingdom, which was later renamed Yugoslavia, was perceived to be was largely dominated by the Serbs, who saw it as a revival of their ancient Serbian Empire or Greater Serbia. Those in favor of the federation saw it as the best defense against Italian expansion along the Adriatic. The Serbian royal family ruled the new kingdom. Official policy in Yugoslavia would be to suppress national identity in favor of a common, Yugoslavian trans-national identity. When Yugoslavia collapsed in the early 1990s, Croatia seceded from the federation to form an independent sovereign state after encountering attempts by Serbian leader, Slobodan Milosovich, to block a Croat's nomination to the revolving Presidency. The image of Stjepan Radić was used extensively during the Croatian Spring movement in the early 1970s when Croatians demanded greater freedom and increased democracy within Yugoslavia. He is credited with introducing Western notions of democracy into Croatia. A pacifist, he believed in the ultimate power of the human spirit to rise above adversity. The party in Croatia today that traces its origins to Radić's CPP, and which proudly acknowledges this legacy, is committed to democracy, peace, the rule of law, care for the environment and social justice all of which is based on the "principles of humanity."[1]

Biography

Lead up to the first Yugoslavia

Stjepan was born in a small Slavonian village Trebarjevo Desno. He attended University of Zagreb and the University of Prague at different times but was expelled or banned for his political opinions regarding Croatia's autonomy from Hungary. On one occasion he burned he Hungarian flag. He was jailed for four months in 1888. He later visited Moscow and Paris where in 1897 he became a student at the Free School of Political Science, graduating cum laude having written his thesis on "Contemporary Croatia and Southern Slavs."[2] Returning to Croatia, he was again jailed in 1901. Appointed secretary to the coalition of opposition parties, in 1905 he co-founded the Peasants Party with his brother, with whom he co-edited the party newspaper, the "Dom" (Home). By 1908, the party had two seats in the Parliament, one of which was occupied by Stjepan.

It was after World War I, however, that he rose to political prominence among Croats for his opposition to merging Croatia with the Kingdom of Serbia without guarantees for Croatian autonomy. On November 24, 1918, he famously urged delegates attending a session that would decide the country's political future not to "rush like drunken geese into fog"—he feared that Croatia would become at best a minor partner within a Serb-dominated state.

Under the pressure from the Great powers (British Empire, France, United States), as well as honoring the secret deals that were struck between the Antanta and the Kingdom of Serbia, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was established and two representatives of Radić's party (by then named the Croatian Common-people Peasant Party) were appointed to the Provisional Representation which served as a parliament until elections for the Constituent could be held. The parties representatives, however, decided not to take their seats.

Arrest

On the 8th of March, 1919, the central committee passed a resolution that declared that "Croatian citizens do not recognize the so called Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes under the Karađorđević dynasty because this kingdom was proclaimed other than by the Croatian Sabor and without any mandate of the Croatian People." The full statement was translated into French and sent abroad and provoked a decision by the government to arrest Radić along with several other party members.

He was to be held some 11 months until February 1920, just before the first parliamentary elections of the Kingdom of SHS, which were held in November. The result of the November was 230,590 votes, which equaled to 50 seats in the parliament out of 419. Before the first sitting of parliament, after a massive rally held in front of 100,000 people in Zagreb, Stjepan Radić and the CCPP (which after the rally changed the party's name to CRPP - Croatian Republican Peasant Party) held and extraordinary meeting, in which a motion was put forward and voted on that the CRPP will not be part of parliamentary discussions before matters are first resolved with Serbia on the matters of governance, the most sticking issues being the memorization of the Croatian people and the overt powers of the King with the central government in Belgrade.

The new Constitution

On the 12th of December, 1920, the Parliament of SHS had their first sitting, without the representatives of CPP (50 representatives) and the Croatian Party of Rights (two representatives). On the 28th of June, 1921, the Constitution of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Vidovdanski ustav, or Vidovdan Constitution) was made law after a vote of 223 representatives out of the present 285, the total number representatives in the parliament being 419, which is only 53.2 percent of the possible votes, or if looked at the number of present representatives it is a more impressive 78.24 percent. The representatives’ turnout and subsequent vote is quite poor considering that it was a constitutive parliament, which was supposed to have created the new constitution.

In the next parliamentary elections, which were held in March 1923, the stance of Stjepan Radić and the CPP against the central government managed to turn into extra votes. The results of the election were, 70 seats or 473.733 votes, which represented the majority of the Croatian vote in Northern and Southern parts of Croatia, as well as the Croatian votes in Bosnia, as well as Herzegovina.

Again imprisoned

Radić still held on to the idea of an independent Croatia, and kept the party out of parliament in protest. This in effect afforded Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić the opportunity to consolidate power and strengthen his Serb-dominated government. Returning from an unsanctioned overseas trip in 1923 in which Stjepan Radić visited England (for five months), Austria (five months) and the Soviet Union (two months). Upon his return in 1924, Radić was arrested in Zagreb and sentenced for associating with Soviet Communists and imprisoned. The trip was used for the purpose of internationalizing the plight of Croatians in the Kingdom of SHS.

After his release, Stjepan Radić soon reentered politics, but this was not without problems. On the 23rd of December, the Serb dominated central government declared that the political party CRPP was in contravention of the Internal security law of 1921 in the infamous Obznana declaration, and this was confirmed by King Alexander on the 1st of January, 1924, thus arresting the CRPP executive on the 2nd of January, 1925, and finally arresting Stjepan Radić on the 5th of January.

After the parliamentary elections in February 1925, the CRPP even with its whole executive team behind bars, and with only Stjepan Radić at its helm, CRPP managed to win 67 parliamentary seats with at total of 532,872 votes. Even though the vote count was higher than the previous election, the careful carving up of the electoral boundaries by the central government ensured that CRPP received less parliamentary seats. In order to increase his negotiating power the CRPP entered into a coalition with the Democratic party (Demokratska stranka), Slovenian peoples party (Slovenska ljudska stranka) and the Yugoslav Muslim Organization (Jugoslavenska muslimanska organizacija).

Return to the parliament

Immediately after the parliamentary elections in March 1925, the CRPP changed the party name to Croatian Peasant Party (Hrvatska seljačka stranka). With the backing of the coalition partners, the CPP made an agreement with the major conservative Serbian party, the People's Radical Party (Narodna radikalna stranka), in which a power sharing arrangement was struck, as well as a deal to release the CPP executive from jail. The CPP had to make certain concessions like recognizing the central government and the rule of the monarch, as well as the Vidovdan constitution in front of the full parliament on March 27, 1925. Stjepan Radić was made the Minister for Education, whereas other CPP party members obtained ministerial posts: Pavle Radić, dr. Nikola Nikić, dr. Benjamin Šuperina and dr. Ivan Krajač. This power sharing arrangement was cut short after the passing away of the president of the Peoples Radical Party, Nikola Pašić, on December 10, 1925.

Radić soon resigned his ministerial post in 1926 and returned to the opposition, and in 1927 entered into a coalition with Svetozar Pribićević, president of the Independent Democratic Party, a leading party of the Serbs in Croatia. The Peasant-Democrat coalition had a real chance to end the Radicals' long-time stranglehold control of the Parliament. Previously they had long been opponents, but the Democrats became disillusioned with the Belgrade bureaucracy and restored good relations with the Peasant Party with which they were allies in the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. With this arrangement, Stjepan Radić managed to obtain a parliamentary majority in 1928. However, he was not able to form a government. The Peasant-Democrat coalition was opposed by some of the Croatian elite, like Ivo Andrić, who even regarded the followers of the CPP as "...fools following a blind dog..." (the blind dog being Stjepan Radić).

Assassination in the parliament

With the power of the Radical Party now weakened, and the Peasant-Democratic coalition not being able to form a government, the environment in the parliament had became increasingly unstable, contentious and provocational on ethnic lines. Provocations and accusations flew on both sides, in one such session Radić answered one of the provocations with the following: "Our Serbian friends are always reminding us of the price they paid in the war. I would like to invite them to tabulate the costs, so we may square accounts and be on our way." Death threats and threats of violent beatings were made against Stjepan Radić in parliament, without any intervention by the president of the Assembly (Parliamentary speaker). On the morning of June 20, 1928, Radić was warned of the danger of an assassination attempt against him and was begged to stay away from the Assembly for that day. He replied that he was like a soldier in war, in the trenches and as such it was his duty to go but he nevertheless promised not to utter a single word.

In the Assembly, Puniša Račić, a member of Serbian People's Radical Party from Montenegro, got up and made a provocative speech which produced a stormy reaction from the opposition but Radić himself stayed completely silent. Finally, Ivan Pernar shouted, "thou plundered beys" (referring to accusations of corruption related to him). At this, Puniša Račić drew out a revolver, shot Pernar and went on to shoot Radić and several other CPP delegates.[3] Radić was left for dead and indeed had such a serious stomach wound that he died several months later at the age of 57. His burial was massively attended and his death was seen as causing a permanent rift in Croat-Serb relations in the old Yugoslavia.

His assassin was "sentenced" to confinement in a luxury villa in Serbia, where he was tended to by servants.

Following the political crisis triggered by the shooting, in January 1929, King Aleksandar Karađorđević abolished the constitution, dissolved parliament, and declared a royal dictatorship, changing the country into the first Yugoslavia and oppressing national sentiments.

In Croatia, Radić is regarded as having stood above party politics to defend Croatian identity, culture and statehood. He is credited with introducing Western notions of democracy into Croatia and with a deep belief in social justice and humanitarian values. He was a pacifist, too, who used the political arena to pursue his goals.[2] Radić is buried in the Mirogoj cemetery in Zagreb.

Tribute

Ivan Goran Kovačić (1913-1943) who is considered to be one of the greatest Croatian poets and writers wrote this tribute to the memory of the slain leader:

- EYES OF STJEPAN RADIC

They were not made for mundane horizons

Firmly they looked afar, far to the century’s end.

Objects and images too near were veiled from them

Because they too clearly saw the splendor of the Great Spring.

The wrinkles around them drew a silent smile;

Rocking in the cradle it lives on long after death.

Then they looked out over the swelling and turgid sea

In which his thought was a silvery fish.

O gentle, dead eyes gouged out by bloody hands

Too powerful for mortal lot, unattainably remote –

Now you hover everywhere, over village, plain and people.

The sea cradles you as the sun and bears you as rivers of pearls.

Head bowed, a giant stalks little Croatia

Carrying the gentle dead eyes in his rough palm.[2]

Philosophy

Radić and his brother were influenced by the philosophy of the French Revolution, which was essentially humanist. His focus on the peasants was driven by the desire to achieve true equality for members of this class, since while serfdom had been abolished in 1848 they remained socially and economically disadvantaged. He passionately believed in the sovereignty of the people and saw the United States Constitution as a fundamental document in the arena of rights and freedoms. He believed in "self-determination of the people, the inviolability of the individual, freedom of movement, the sanctity of the home, security from the censorship of mail and equality of the sexes."[2] Croatian writers stress his pacifism and commitment to humanitarian values.

Legacy

Radić's violent death turned him into a martyr and he was turned into an icon of political struggle for the peasantry and the working class, as well as an icon of Croatian patriots. The iconography of Stjepan Radić was later used not only by his successor Vladko Maček, but also by other political options in Croatia: right wing or left wing.

The Ustaše used the death of Stjepan Radić as proof of Serbian hegemony, and as an excuse for their treatment of Serbs, however many leading CPP figures were imprisoned or killed by the Ustashe to whom they were political opponents. The Partisans on the other hand, used this as a recruiting point with CPP members who were disillusioned with the Independent State of Croatia, and later had one brigade named after Antun and Stjepan Radić in 1943.

The image of Stjepan Radić was used extensively during the Croatian Spring movement in the early 1970s. There are many folk groups, clubs, primary and secondary schools which bare the name of Stjepan Radić. Many Croatian cities have streets, squares in his name and statues of Stjepan Radić are common. The picture of Stjepan Radić appears on the 200 kuna banknote.

In 1997, a poll in Croatian weekly Nacional named Stjepan Radić as the most admired Croatian historic personality. The Croatian Peasant Party regards Radić as its founder building on the "humanistic and peace-building philosophy of the Radić brothers and their political successors."[1]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 HSS Croatian Peasant Party History and Program HRVATSKA SELJAČKA STRANKA. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Jure Petricevic, The Significance of Stepjan Radic to the Croatian Nation in the Past and Present. This essay first appeared in the book "Hrvatski Portreti" – (Croatian Portraits) published by Hrvatska Revija in Switzerland, 1973. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ Zvonimir Kulundžić, Atentat na Stjepana Radića (The assassination of Stjepan Radić) Zagreb, HR: "Stvarnost", 1967.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Biondich, Mark. Stjepan Radić, the Croat Peasant Party, and the politics of mass mobilization, 1904-1928. Toronto, CA: University of Toronto Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0802047274

- Goldstein, Ivo. Croatia: a history. Montréal, CA: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0773520165

- Magaš, Branka. Croatia through history: the making of a European state. London, UK: Saqi, 2007. ISBN 978-0863567759

- Perić, Ivo. Stjepan Radić, 1871-1928. Zagreb, HR: Dom i svijet, 2003. ISBN 978-9536491889

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.