Joan of Arc

| Saint Joan of Arc | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1412, Domrémy (later renamed Domrémy-la-Pucelle), France |

| Died | May 30, 1431, Rouen, France |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | April 18, 1909 by Pius X |

| Canonized | May 16, 1920 by Benedict XV |

| Calendar of saints | May 30 |

| Patron saint | captives; France; martyrs; opponents of Church authorities; people ridiculed for their piety; prisoners; rape victims; soldiers; Women Appointed for Voluntary Emergency Service; Women's Army Corps |

| In the face of your enemies, in the face of harassment, ridicule, and doubt, you held firm in your faith. Even in your abandonment, alone and without friends, you held firm in your faith. Even as you faced your own mortality, you held firm in your faith. I pray that I may be as bold in my beliefs as you, St. Joan. I ask that you ride alongside me in my own battles. Help me be mindful that what is worthwhile can be won when I persist. Help me hold firm in my faith. Help me believe in my ability to act well and wisely. Amen. Prayer to Joan of Arc for Faith | |

Joan of Arc, also Jeanne d'Arc[1] (1412[2] – May 30, 1431), is a national heroine of France and a saint of the Roman Catholic Church. She had visions, from God, that led to the liberation of her homeland from English dominance in the Hundred Years' War; however she was captured, tried for heresy and martyred. Today she is honored as an example of female courage and leadership, piety, and devotion, as well as a French patriot. Though illiterate, uneducated, dying at the young age of 19, her impact on history is enormous, stemming from the belief of a 16-year-old, that she was an instrument of God.

Joan's career began when the then-uncrowned King Charles VII sent her to the siege of Orléans as part of a relief mission. She gained prominence when she overcame the disregard of veteran commanders and ended the siege in only nine days. Several more swift victories led to Charles VII's coronation at Rheims and settled the disputed succession to the throne.

The renewed French confidence outlasted Joan of Arc's own brief career. She refused to leave the field when she was wounded during an attempt to recapture Paris that fall. Hampered by court intrigues, she led only minor companies from then on, and fell prisoner during a skirmish near Compiègne the following spring. A politically-motivated trial convicted her of heresy. The English regent, John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, had her burnt at the stake in Rouen. Some twenty-four years later, Pope Callixtus III reopened Joan of Arc's case, and the new finding overturned the original conviction.[3] Her piety to the end impressed the retrial court.

Her original trial is an example of how the charge of heresy could be used, at that time, to silence women whose leadership threatened the male dominated status quo of Church and society. Pope Benedict XV canonized her on May 16, 1920.

Joan of Arc has remained an important figure in Western culture. From Napoleon to the present, French politicians of all leanings have invoked her memory. Major writers and composers, including William Shakespeare, Voltaire, Friedrich Schiller, Giuseppe Verdi, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Samuel Clemens, George Bernard Shaw, and Bertolt Brecht, have created works about her, and depictions of her continue to be prevalent in film, television, and song.

Background

The period that preceded Joan of Arc's career was the lowest era in French history until the Nazi occupation. The French king at the time of Joan's birth, Charles VI, suffered bouts of insanity and was often unable to rule. Two of the king's cousins, John, Duke of Burgundy (known as John the Fearless) and Louis of Valois, Duke of Orléans, quarreled over the regency of France and the guardianship of the royal children. The dispute escalated to accusations of an extramarital affair with Queen Isabeau of Bavaria and kidnappings of the royal children, and culminated when John the Fearless ordered the assassination of Louis in 1407. The factions loyal to these two men became known as the Armagnacs and the Burgundians. The English king, Henry V, took advantage of this turmoil and invaded France. The English won a dramatic Battle of Agincourt in 1415, and proceeded to capture northern French towns. The future French king, Charles VII, assumed the title of dauphin as heir to the throne at the age of 14 after all four of his older brothers had died. His first significant official act was to conclude a peace treaty with John the Fearless in 1419. This ended in disaster when Armagnac partisans murdered John the Fearless during a meeting under Charles's guarantee of protection. The new duke of Burgundy, Philip III, Duke of Burgundy (known as Philip the Good), blamed Charles and entered an alliance with the English. Large sections of France fell to conquest.

In 1420, Queen Isabeau of Bavaria concluded the Treaty of Troyes, which granted the royal succession to Henry V and his heirs in preference to her son Charles. This agreement revived rumors about her supposed affair with the late duke of Orléans and raised fresh suspicions that the dauphin was a royal bastard rather than the son of the king. Henry V and Charles VI died within two months of each other in 1422, leaving an infant, Henry VI of England, the nominal monarch of both kingdoms. Henry V's brother John, 1st Duke of Bedford, acted as regent.

By 1429, nearly all of northern France, and some parts of the southwest, were under foreign control. The English ruled Paris and the Burgundians ruled Rheims. The latter city was important as the traditional site of French coronations and consecrations, especially since neither claimant to the throne of France had been crowned. The English had laid siege to Orléans, which was the only remaining loyal French city north of the Loire River. Its strategic location along the river made it the last obstacle to an assault on the remaining French heartland. In the words of one modern historian, "On the fate of Orléans hung that of the entire kingdom." No one was optimistic that the city could win the siege.

Life

Childhood

Joan of Arc was born in the village of Domrémy-la-Pucelle in the province of Lorraine to Jacques D'Arc and Isabelle Romée. Her parents owned about 50 acres of land and her father supplemented his farming work with a minor position as a village official, collecting taxes and heading the town watch. They lived in an isolated patch of northeastern territory that remained loyal to the French crown despite being surrounded by Burgundian lands. Several raids occurred during Joan of Arc's childhood, and on one occasion her village was burned.

Joan later testified that she experienced her first vision around 1424. She would report that St. Michael, St. Catherine, and St. Margaret told her to drive out the English and bring the dauphin to Rheims for his coronation. At the age of 16 she asked a kinsman, Durand Lassois, to bring her to nearby Vaucouleurs, where she petitioned the garrison commander, Count Robert de Baudricourt, for permission to visit the royal French court at Chinon. Baudricourt's sarcastic response did not deter her. She returned the following January and gained support from two men of standing: Jean de Metz and Bertrand de Poulegny. Under their auspices she gained a second interview, where she made an apparently miraculous prediction about a military reversal near Orléans.

Rise to prominence

Baudricourt granted her an escort to visit Chinon after news from the front confirmed her prediction. She made the journey through hostile Burgundian territory in male disguise. Upon arriving at the royal court, she impressed Charles VII during a private conference. He then ordered background inquiries and a theological examination at Poitiers to verify her morality. During this time, Charles's mother-in-law, Yolande of Aragon, was financing a relief expedition to Orléans. Joan of Arc petitioned for permission to travel with the army and bear the arms and equipment of a knight. Because she had no funds of her own, she depended on donations for her armor, horse, sword, banner, and entourage. Historian Stephen W. Richey explains her rise as the only source of hope for a regime that was near collapse:

After years of one humiliating defeat after another, both the military and civil leadership of France were demoralized and discredited. When the Dauphin Charles granted Joan’s urgent request to be equipped for war and placed at the head of his army, his decision must have been based in large part on the knowledge that every orthodox, every rational, option had been tried and had failed. Only a regime in the final straits of desperation would pay any heed to an illiterate farm girl, who heard voices from God were instructing her to take charge of her country’s army and lead it to victory.[4]

Joan of Arc arrived at the siege of Orléans on April 29, 1429, but Jean d'Orléans, the acting head of the Orléans ducal family, excluded her from war councils and failed to inform her when the army engaged the enemy. She burst into the meetings where she had not been invited, disregarded the veteran commanders' decisions, appealed to the town's population, and rode out to each skirmish, where she placed herself at the extreme front line. The extent of her actual military leadership is a subject of historical debate. Traditional historians, such as Edouard Perroy, conclude that she was a standard bearer whose primary effect was on morale.[5] This type of analysis usually relies on the condemnation trial testimony, where Joan of Arc stated that she preferred her standard to her sword. Recent scholarship that focuses on the rehabilitation trial testimony more often suggests that her fellow officers esteemed her as a skilled tactician and a successful strategist. Richey asserts "She proceeded to lead the army in an astounding series of victories that reversed the tide of the war."[4] In either case, historians agree that the army enjoyed remarkable success during her brief career.[6]

Leadership

Joan of Arc defied the cautious strategy that had previously characterized French leadership, pursuing vigorous frontal assaults against outlying siege fortifications. After several of these outposts fell, the English abandoned other wooden structures and concentrated their remaining forces at the stone fortress that controlled the bridge, les Tourelles. On May 7, the French assaulted the Tourelles. Contemporaries acknowledged Joan as the hero of the engagement, during which at one point she pulled an arrow from her own shoulder and returned, still wounded, to lead the final charge.[7]

The sudden victory at Orléans led to many proposals for offensive action. The English expected an attempt to recapture Paris; French counterintelligence may have contributed to that perception. Later, at her condemnation trial, Joan of Arc described a mark that the French command had used in letters for disinformation. In the aftermath of the unexpected victory, she persuaded Charles VII to grant her co-command of the army with Duke John II of Alençon, and gained royal permission for her plan to recapture nearby bridges along the Loire as a prelude to an advance on Rheims and a coronation. Her proposal was considered bold because Rheims was roughly twice as far away as Paris. [8]

The army recovered Jargeau on June 12, Meung-sur-Loire on June 15, then Beaugency on June 17. The duke of Alençon agreed to all of Joan of Arc's decisions. Other commanders, including Jean d'Orléans, had been impressed with her performance at Orléans, and became strong supporters of her. Alençon credited Joan for saving his life at Jargeau, where she warned him of an imminent artillery attack.[9] During the same battle, she withstood a stone cannonball blow to her helmet as she climbed a scaling ladder. An expected English relief force arrived in the area on June 18, under the command of Sir John Fastolf. The Battle of Patay might be compared to Agincourt in reverse: The French vanguard attacked before the English archers could finish defensive preparations. A rout ensued that decimated the main body of the English army and killed or captured most of its commanders. Fastolf escaped with a small band of soldiers and became the scapegoat for the English humiliation. The French suffered minimal losses.[8]

The French army set out for Rheims from Gien-sur-Loire on June 29, and accepted the conditional surrender of the Burgundian-held city of Auxerre on July 3. Every other town in their path returned to French allegiance without resistance. Troyes, the site of the treaty that had tried to disinherit Charles VII, capitulated after a bloodless four-day siege.[8] The army was in short supply of food by the time it reached Troyes. Edward Lucie-Smith cites this as an example of why Joan of Arc was more lucky than skilled: A wandering friar named Brother Richard had been preaching about the end of the world at Troyes, and had convinced local residents to plant beans, a crop with an early harvest. The hungry army arrived just as the beans had ripened.[10]

Rheims opened its gates on July 16. The coronation took place the following morning. Although Joan and the duke of Alençon urged a prompt march on Paris, the royal court pursued a negotiated truce with the duke of Burgundy. Duke Philip the Good broke the agreement, using it as a stalling tactic to reinforce the defense of Paris.[8] The French army marched through towns near Paris during the interim and accepted more peaceful surrenders. The duke of Bedford headed an English force and confronted the French army in a standoff on August 15. The French assault at Paris ensued on September 8. Despite a crossbow bolt wound to the leg, Joan of Arc continued directing the troops until the day's fighting ended. The following morning, she received a royal order to withdraw. Most historians blame French grand chamberlain Georges de la Trémoille for the political blunders that followed the coronation.[6]

Capture and trial

After minor action at La-Charité-sur-Loire in November and December, Joan went to Compiègne the following April to defend against an English and Burgundian siege. A skirmish on May 23, 1430, led to her capture. When she ordered a retreat, she assumed the place of honor as the last to leave the field. Burgundians surrounded the rear guard.

It was customary for a war captive's family to raise a ransom. Joan of Arc and her family lacked the financial resources. Many historians fault Charles VII for failing to intervene. She attempted several escapes, on one occasion leaping from a 70-foot tower to the soft earth of a dry moat. The English government eventually purchased her from Duke Philip of Burgundy. Bishop Pierre Cauchon of Beauvais, an English partisan, assumed a prominent role in these negotiations and her later trial.

Joan's trial for heresy was politically motivated. The duke of Bedford claimed the throne of France for his nephew Henry VI. She was responsible for the rival coronation, and condemning her was an attempt to discredit her king. Legal proceedings commenced on January 9, 1431 at Rouen, the seat of the English occupation government. The procedure was irregular on a number of points.

To summarize some of the trials problems, the jurisdiction of promoter Bishop Cauchon was a legal fiction. He owed his appointment to his partisanship. The English government financed the entire trial. Clerical notary Nicolas Bailly, commissioned to collect testimony against her, could find no adverse evidence.[11] Without this, the court lacked grounds to initiate a trial. Opening one anyway, it denied her right to a legal adviser.

The trial record demonstrates her exceptional intellect and faith. The transcript's most famous exchange is an exercise in subtlety. "Asked if she knew she was in God's grace, she answered: 'If I am not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me.'"[12] The question was a scholarly trap. Church doctrine held that no one could be certain of being in God's grace. If she had answered yes, then she would have convicted herself of heresy. If she had answered no, then she would have confessed her own guilt. Notary Boisguillaume would later testify that at the moment the court heard this reply, "Those who were interrogating her were stupefied."[6] In the twentieth century, George Bernard Shaw would find this dialogue so compelling that sections of his play Saint Joan are literal translations of the trial record.[13]

Several court functionaries later testified that significant portions of the transcript were altered in her disfavor. Many clerics served under compulsion, including the inquisitor, and a few even received death threats from the English. Joan should have been confined to an ecclesiastical prison under the supervision of female guards. Instead, the English kept her in a secular prison guarded by their own soldiers. Bishop Cauchon denied Joan's appeals to the Council of Basel and the Pope, which should have stopped the proceeding.[6]

The twelve articles of accusation that summarize the court's finding contradict the already-doctored court record.[12] Illiterate, Joan signed an abjuration document she did not understand under threat of immediate execution. The court substituted a different abjuration in the official record.[12]

Execution

Even at that time, heresy was a capital crime only for a repeat offense. Joan agreed to wear women's clothes when she abjured. A few days later, she was subjected to a sexual assault in prison, possibly by an English lord. She resumed male attire either as a defense against molestation or, in the testimony of Jean Massieu, because her dress had been stolen and she was left with nothing else to wear.[14]

Eyewitnesses described the scene of the execution on May 30, 1431. Tied to a tall pillar, she asked two of the clergy, Martin Ladvenu and Isambart de la Pierre, to hold a crucifix before her. She repeatedly called out "in a loud voice the holy name of Jesus, and implored and invoked without ceasing the aid of the saints of Paradise." After she expired, the coals were raked to expose her charred body so that no one could claim she had escaped alive, then burned the body twice more to reduce it to ashes and prevent any collection of relics. Her remains were cast into the Seine River. The executioner, Geoffroy Therage, later stated that he had "...a great fear of being damned, [because] he had burned a saint."[15]

Retrial

A posthumous retrial opened almost twenty years later as the war ended. Pope Callixtus III authorized this proceeding, now known as the "rehabilitation trial," at the request of Inquisitor-General Jean Brehal and Joan of Arc's mother Isabelle Romée. Investigations started with an inquest by clergyman Guillaume Bouille. Brehal conducted an investigation in 1452, and a formal appeal followed in November 1455. The appellate process included clergy from throughout Europe and observed standard court procedure. A panel of theologians analyzed testimony from 115 witnesses. Brehal drew up his final summary in June 1456, which describes Joan as a martyr and implicates the late Pierre Cauchon with heresy for having convicted an innocent woman in pursuit of a secular vendetta. The court declared her innocence on July 7, 1456.[16]

Clothing

Joan of Arc wore men's clothing between her departure from Vaucouleurs and her abjuration at Rouen. Her stated motivation was for self-preservation and stealth. This raised theological questions in her own era and raised other questions in the twentieth century. The technical reason for her execution was a Biblical clothing law,(Deuteronomy 22:5) but the rehabilitation trial reversed the conviction in part because the condemnation proceeding had failed to consider the doctrinal exceptions to that law.[17]

Doctrinally speaking, she was safe to disguise herself as a page during a journey through enemy territory and she was safe to wear armor during battle. The Chronique de la Pucelle states that it deterred molestation while she was camped in the field. Clergy who testified at her rehabilitation trial affirmed that she continued to wear male clothing in prison to deter molestation and rape.[18] Preservation of chastity was another justifiable reason for cross-dressing, because such apparel would have slowed an assailant. According to medieval clothing expert Adrien Harmand, she wore two layers of pants attached to the doublet with twenty fastenings. The outer pants were made of a boot-like leather.[19]

She referred the court to the Poitiers inquiry when questioned on the matter during her condemnation trial. The Poitiers record no longer survives, but circumstances indicate the Poitiers clerics approved her practice.[20] In other words, she had a mission to do a man's work so it was fitting that she dressed the part. She also kept her hair cut short through her military campaigns and while in prison. Her supporters, such as the theologian Jean Gerson, defended her hairstyle, as did Inquisitor Brehal during the Rehabilitation trial.[21]

According to Francoise Meltzer, "The depictions of Joan of Arc tell us about the assumptions and gender prejudices of each succeeding era, but they tell us nothing about Joan's looks in themselves. They can be read, then, as a semiology of gender: how each succeeding culture imagines the figure whose charismatic courage, combined with the blurring of gender roles, makes her difficult to depict."[22]

Visions

Joan of Arc's religious visions have interested many people. All agree that her faith was sincere. She identified St. Margaret, St. Catherine, and St. Michael as the source of her revelations. Devout Roman Catholics regard her visions as divine inspiration.

Scholars who propose psychiatric explanations such as schizophrenia consider Joan a figurehead rather than an active leader.[10] Among other hypotheses are a handful of neurological conditions that can cause complex hallucinations in otherwise sane and healthy people, such as temporal lobe epilepsy.

Psychiatric explanations encounter some difficulties. One is the slim likelihood that a mentally ill person could gain favor in the court of Charles VII. This king's own father had been popularly known as "Charles the Mad" and much of the political and military decline that had occurred in France during the previous decades could be attributed to the power vacuum that his episodes of insanity had produced. The old king had believed he was made of glass, a delusion no courtier had mistaken for a religious awakening. Fears that Charles VII would manifest the same insanity may have factored in the attempt to disinherit him at Troyes. Contemporaries of the next generation would attribute inherited madness to the breakdown that England's King Henry VI was to suffer in 1453: Henry VI was nephew to Charles VII and grandson to Charles VI. As royal counselor Jacques Gélu cautioned upon Joan of Arc's arrival at Chinon, "One should not lightly alter any policy because of conversation with a girl, a peasant...so susceptible to illusions; one should not make oneself ridiculous in the sight of foreign nations..."[6]

Joan of Arc remained astute to the end of her life. Rehabilitation trial testimony frequently marvels at her intelligence. "Often they [the judges] turned from one question to another, changing about, but, notwithstanding this, she answered prudently, and evinced a wonderful memory."[23] Her subtle replies under interrogation even forced the court to stop holding public sessions.[6]

The only detailed source of information about Joan of Arc's visions is the condemnation trial transcript, a complex and problematic document in which she resisted the court's inquiries and refused to swear the customary oath on the subject of her revelations. Régine Pernoud, a prominent historian, was sometimes sarcastic about speculative medical interpretations: in response to one such theory alleging that Joan of Arc suffered from bovine tuberculosis as a result of drinking unpasteurized milk, Pernoud wrote that if drinking unpasteurized milk can produce such potential benefits for the nation, then the French government should stop mandating the pasteurization of milk.[24] This is a profound example of a lack of faith in the unseen.

Legacy

The Hundred Years' War continued for 22 years after Joan of Arc's death. Charles VII succeeded in retaining legitimacy as king of France in spite of a rival coronation held for Henry VI in December 1431 on the boy king's tenth birthday. Before England could rebuild its military leadership and longbow corps lost during 1429, the country also lost its alliance with Burgundy at the Treaty of Arras in 1435. The duke of Bedford died the same year and Henry VI became the youngest king of England to rule without a regent. That treaty and his weak leadership were probably the most important factors in ending the conflict. Kelly DeVries argues that Joan of Arc's aggressive use of artillery and frontal assaults influenced French tactics for the rest of the war.[8]

Joan of Arc became a legendary figure for the next four centuries. The main sources of information about her were chronicles. Five original manuscripts of her condemnation trial surfaced in old archives during the nineteenth century. Soon historians also located the complete records of her rehabilitation trial, which contained sworn testimony from 115 witnesses, and the original French notes for the Latin condemnation trial transcript. Various contemporary letters also emerged, three of which carry the signature "Jehanne" in the unsteady hand of a person learning to write.[6] This unusual wealth of primary source material is one reason DeVries declares, "No person of the Middle Ages, male or female, has been the subject of more study than Joan of Arc.[8]

She came from an obscure village and rose to prominence when she was barely more than a child and she did so as an uneducated peasant. French and English kings had justified the ongoing war through competing interpretations of the thousand-year-old Salic law. The conflict had been an inheritance feud between monarchs. Joan of Arc gave meaning to appeals such as that of squire Jean de Metz when he asked, "Must the king be driven from the kingdom; and are we to be English?"[25] In the words of Stephen Richey, "She turned what had been a dry dynastic squabble that left the common people unmoved except for their own suffering into a passionately popular war of national liberation." [4] Richey also expresses the breadth of her subsequent appeal:

The people who came after her in the five centuries since her death tried to make everything of her: demonic fanatic, spiritual mystic, naive and tragically ill-used tool of the powerful, creator and icon of modern popular nationalism, adored heroine, saint. She insisted, even when threatened with torture and faced with death by fire, that she was guided by voices from God. Voices or no voices, her achievements leave anyone who knows her story shaking his head in amazed wonder.[4]

The church declared that a religious play in her honor at Orléans was a pilgrimage meriting an indulgence. Joan of Arc became a symbol of the Catholic League during the sixteenth century. Félix Dupanloup, bishop of Orléans from 1849 to 1878, led the effort for Joan's eventual beatification in 1909. Her canonization followed on May 16, 1920. Her feast day is May 30.

Joan of Arc was a righteous woman. She operated within a religious tradition that believed an exceptional person from any level of society might receive a divine calling. She expelled women from the French army. Nonetheless, some of her most significant aid came from women. Charles VII's mother-in-law, Yolande of Aragon, confirmed Joan's virginity and financed her departure to Orléans. Joan of Luxembourg, aunt to the count of Luxembourg who held Joan of Arc after Compiegne, alleviated Joan of Arc's conditions of captivity and may have delayed her sale to the English. Finally, Anne of Burgundy, the duchess of Bedford and wife to the regent of England, declared Joan a virgin during pretrial inquiries.[26] For technical reasons this prevented the court from charging Joan with witchcraft. Ultimately this provided part of the basis for Joan's vindication and sainthood. From Christine de Pizan to the present, women have looked to Joan of Arc as a positive example of a brave and active young woman of courage, who in the face of incredible difficulty and persecution stood up for God and country with no fear of the consequences.

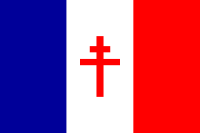

Joan of Arc has been a political symbol in France since the time of Napoleon. Liberals emphasized her humble origins. Early conservatives stressed her support of the monarchy. Later conservatives recalled her nationalism. During World War II, both the Vichy Regime and the French Resistance used her image: Vichy propaganda remembered her campaign against the English with posters that showed British warplanes bombing Rouen and the ominous caption: "They Always Return to the Scene of Their Crimes." The resistance emphasized her fight against foreign occupation and her origins in the province of Lorraine, which had fallen under Nazi control.

Traditional Catholics, especially in France, also use her as a symbol of inspiration, often comparing the Society of St. Pius X founder and excommunicate, Roman Catholic Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre's excommunication in 1988 to Joan of Arc's excommunication. Three separate vessels of the French Navy have been named after Joan of Arc, including a FS Jeanne d'Arc helicopter carrier currently in active service. In her lifetime she was an object of cultural war between the French and the English; she continues to be claimed as a symbol today in different ways by different causes and political parties. The French civic holiday in her honor is the second Sunday of May.

Notes

- ↑ Joan of Arc's name was written in a variety of ways, particularly prior to the mid-nineteenth century. See Regine Pernoud and Marie-Veronique Clin, Joan of Arc: Her Story (New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1999, ISBN 0312227302).

- ↑ Modern biographical summaries often assert a birthdate of January 6. None of the witnesses at her rehabilitation trial provide a birthdate, and the event was probably not recorded. The practice of parish registers for non-noble births did not begin until several generations later. In reality, Joan of Arc did not know her own exact age. Medieval Sourcebook: The Trial of Joan of Arc, 38 Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ A tribunal led by Inquisitor-General Brehal retried her case after the French won the war. The new verdict overturned the original conviction and described the earlier proceeding as "corruption, cozenage, calumny, fraud and malice." Concluding Document Virginia Frohlick-Saint Joan of Arc Center. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Stephen W. Richey, Joan of Arc: A Military Appreciation The Saint Joan of Arc Center, 2000. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Edouard Perroy, The Hundred Years War (Capricorn Books, 1965, ISBN 978-0571166978).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Regine Pernoud and Marie-Veronique Clin, Joan of Arc: Her Story (New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1999, ISBN 0312227302).

- ↑ Devout Catholics regard this as proof of her divine mission. At Chinon and Poitiers she had declared that she would give a sign at Orléans. The lifting of the siege gained her the support of prominent clergy such as the Archbishop of Embrun and theologian Jean Gerson, who both wrote supportive treatises immediately following this event.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Kelly Devries, Joan of Arc: A Military Leader (Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 1999, ISBN 0750918055).

- ↑ Joan's Friends Part 1 Virginia Frohlick-Saint Joan of Arc Center. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Edward Lucie-Smith, Joan of Arc (Penguin Books Ltd, 2000, ISBN 978-0141390000).

- ↑ The Second Inquiry: 1455 Virginia Frohlick-Saint Joan of Arc Center. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Medieval Sourcebook: The Trial of Joan of Arc Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ George Bernard Shaw, Saint Joan: A Chronicle Play in Six Scenes and An Epilogue (Dover Publications, 2019, ISBN 978-0486836638).

- ↑ Continuation of the First Inquiry Virginia Frohlick-Saint Joan of Arc Center. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Polly Schoyer Brooks, Beyond the Myth: The Story of Joan of Arc (HMH Books for Young Readers, 1999, ISBN 978-0395981382).

- ↑ Concluding Document Virginia Frohlick-Saint Joan of Arc Center. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Most notably Thomas Aquinas, "Outward apparel should be consistent with the state of the person according to general custom. Hence it is in itself sinful for a woman to wear man’s clothes, or vice-versa; especially since this may be the cause of sensuous pleasure; and it is expressly forbidden in the Law (Deut 22).... Nevertheless this may be done at times on account of some necessity, either in order to hide oneself from enemies, or through lack of other clothes, or for some other such reason." (Summa Theologiae II, II, question 169, article 2, reply to objection 3)

- ↑ Saint Joan of Arc's Trial of Nullification The Saint Joan of Arc Center. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Adrien Harmand, Jeanne d'Arc, son costume, son armure (French) Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Arrival at Chinon and the Trial at Poitiers Virginia Frohlick-Saint Joan of Arc Center. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Deborah Fraioli, Joan of Arc: The Early Debate (London: Boydell Press, 2002, ISBN 0851158803).

- ↑ Francoise Meltzer, For Fear of the Fire: Joan of Arc and the Limits of Subjectivity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001, ISBN 0226519821).

- ↑ Rouen Testimony Part 1 Virginia Frohlick-Saint Joan of Arc Center. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ Regine Pernoud, Joan of Arc by Herself and Her Witnesses (London: Scarborough House, 1994, ISBN 0812812603).

- ↑ Vaucouleurs and Joinery to Chinon Virginia Frohlick-Saint Joan of Arc Center. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ↑ These tests, which Joan of Arc's confessor describes as hymen investigations, are not reliable measures of virginity. However, they signified approval from matrons of the highest social rank at key moments of Joan of Arc's life.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brooks, Polly Shoyer. Beyond the Myth: The Story of Joan of Arc. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1999. ISBN 0397324227

- de Charmettes, Philippe-Alexandre Le Brun. History of Joan of Arc Called the Maid of Orleans, drawn from her own declarations, of one hundred forty-four depositions of eyewitnesses, and of the manuscripts of the library of the King and the London Tower. Paris, ED. Artus Bertrand, 1817.

- Devries, Kelly. Joan of Arc: A Military Leader. Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0750918055

- Fraioli, Deborah. Joan of Arc: The Early Debate. London: Boydell Press, 2002. ISBN 0851158803

- Lucie-Smith, Edward. Joan of Arc. Penguin Books Ltd, 2000. ISBN 978-0141390000

- Meltzer, Francoise. For Fear of the Fire: Joan of Arc and the Limits of Subjectivity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. ISBN 0226519821

- Pernoud, Regine. Joan of Arc by Herself and Her Witnesses. London: Scarborough House, 1994. ISBN 0812812603

- Pernoud, Regine. The Retrial of Joan of Arc; The Evidence at the Trial For Her Rehabilitation 1450 - 1456. New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1955. ASIN B0007DZMRG

- Pernoud, Regine and Marie-Veronique Clin. Joan of Arc: Her Story. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1999. ISBN 0312227302

- Perroy, Edouard. The Hundred Years War. trans. W.B. Wells. Capricorn Books, 1965. ISBN 978-0571166978

- Richey, Stephen W. Joan of Arc: The Warrior Saint.. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003. ISBN 0275981037

- Sackville-West, Vita. Saint Joan of Arc. New York: Grove Press, 2001. ISBN 0802138160

- Shaw, George Bernard. Saint Joan: A Chronicle Play in Six Scenes and An Epilogue. Dover Publications, 2019. ISBN 978-0486836638

- Warner, Marina. Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981. ISBN 0520224647

- Wheeler, Bonnie and Charles T. Wood (eds.). Fresh Verdicts on Joan of Arc. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996. ISBN 0815336640

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2025.

- St. Joan of Arc Catholic Encyclopedia

- Joan of Arc Archive by Allen Williamson. Includes a biography, translations and other original research.

- Historial Jeanne d'Arc in Rouen, France.

- Joan of Arc at History.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.