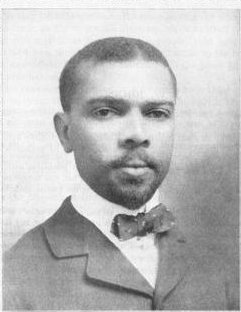

James Weldon Johnson

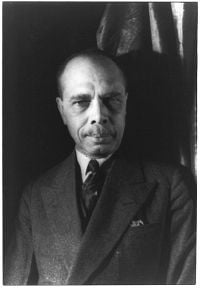

| James Weldon Johnson | |

|---|---|

photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1932 | |

| Born | June 17, 1871 Jacksonville, Florida, United States |

| Died | June 26, 1938 (aged 67) Wiscasset, Maine, United States |

| Occupation | educator, lawyer, diplomat, songwriter, writer, anthropologist, poet, activist |

| Nationality | American |

| Literary movement | Harlem Renaissance |

| Notable work(s) | Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing,” “The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man” |

| Influences | Paul Lawrence Dunbar, Langston Hughes |

James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871 – June 26, 1938) was an American author, politician, diplomat, critic, journalist, poet, anthologist, educator, lawyer, songwriter, and early civil rights activist. Johnson is best remembered for his writing, which includes novels, poems, and collections of folklore. He was also one of the first African-American professors at New York University. Later in life he was a professor of creative literature and writing at Fisk University.

Johnson was a prominent figure of the latter part of the Harlem Renaissance, which marked a turning point for African American literature. Prior to this time, books by African-Americans were primarily read by other black people. With the renaissance, though, African-American literature—as well as black fine art and performance art—began to be absorbed into mainstream American culture.

In addition to his artistic contribution, Johnson served as a United States Consul, with postings to Venezuela and Nicaragua and as general secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Life

Johnson was born in Jacksonville, Florida, the son of Helen Louise Dillet and James Johnson. Johnson was first educated by his mother (a musician and a public school teacher–the first female, black teacher in Florida at a grammar school) and then at Edwin M. Stanton School. At the age of 16 he enrolled at Atlanta University, from which he graduated in 1894. In addition to his bachelor's degree, he also completed some graduate coursework there.[1]

He served in several public capacities over the next 35 years, working in education, the diplomatic corps, civil rights activism, literature, poetry, and music. In 1904 Johnson went on Theodore Roosevelt's presidential Campaign. In 1907 Theodore Roosevelt appointed Johnson as United States consul at Puerto Cabello, Venezuela from 1906-1908 and then Nicaragua from 1909-1913. In 1910 Johnson married Grace Nail, the daughter of a prosperous real estate developer from New York. In 1913 he changed his name officially from James William Johnson to James Weldon Johnson. He became a member of Sigma Pi Phi, various sectors of the Masonic Order and Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. at some point after its founding in 1914.

Education and Law

After graduation he returned to Stanton, a school for African American students in Jacksonville, until 1906, where at the young age of 35 he became principal. Johnson improved education by adding the ninth and tenth grades. In 1897, Johnson was the first African American admitted to the Florida Bar Exam since Reconstruction. In the 1930s Johnson became a Professor of Creative Literature and Writing at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee where he lectured not only on literature but also on a wide range of issues to do with the life and civil rights of black American.

Music

In 1899, Johnson moved to New York City with his brother, J. Rosamond Johnson to work in musical theater. Along with his brother, he produced such hits as "Tell Me, Dusky Maiden" and "Nobody's Looking but the Owl and the Moon." Johnson composed the lyrics of "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing," originally written for a celebration of Lincoln's birthday at Stanton School.[2] This song would later become to be known—and adopted as such by the NAACP—as the Negro National Anthem. The song was entered into the Congressional Record as the official African American National Hymn following the success of a 1990 rendition by singer Melba Moore and a bevy of other recording artists. After successes with their songwriting and music the brothers worked at Broadway and collaborated with producer and director Bob Cole. Johnson also composed the opera Tolosa with his brother J. Rosamond Johnson which satirizes the United States annexation of the Pacific islands.[3]

Diplomacy

In 1906 Johnson was appointed United States consul of Puerto Cabello, Venezuela. In 1909, he transferred to be the US consul of Corinto, Nicaragua.[4] During his work in the foreign service, Johnson became a published poet, with work printed in the magazine The Century Magazine and in The Independent.[5]

Literature and Anthologies

During his six-year stay in South America he completed his most famous book The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man which was published anonymously in 1912. It was only in 1927 that Johnson admitted his authorship, stressing that it was not a work of autobiography but mostly fictional. Other works include The Book of American Negro Spirituals (1925), Black Manhattan (1930), his exploration of the contribution of African-Americans to the cultural scene of New York, and Negro Americans, What Now? (1934), a book calling for civil rights for African-Americans. Johnson was also an accomplished anthologist. Johnson's anthologies provided inspiration, encouragement, and recognition to the new generation of artists who would create the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s.[6]

Harlem Renaissance

By the end of World War I, the fiction of Johnson and the poetry of Claude McKay anticipated the literature that would follow in the 1920s. They described the reality of black life in America and the struggle for racial identity.

The first stage of the Harlem Renaissance started in the late 1910s. 1917 saw the premiere of Three Plays for a Negro Theatre. These plays, written by white playwright Ridgely Torrence, featured black actors' conveying complex human emotions and yearnings. They rejected the stereotypes of the blackface and minstrel show traditions. Johnson in 1917 called the premieres of these plays "the most important single event in the entire history of the Negro in the American Theatre."[7] By the end of the First World War, Johnson, in his fiction and Claude McKay in his poetry, were able to describe the reality of contemporary black life in America.

Poetry

Johnson was also a major poet. Together with Paul Laurence Dunbar, and the works of people like W.E.B Dubois, he helped to ignite the Harlem Renaissance. In 1922, he edited The Book of American Negro Poetry, which the Academy of American Poets calls "a major contribution to the history of African-American literature."[5] One of the works for which he is best remembered today, God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse, was published in 1927 and celebrates the tradition of the folk preacher. In 1917, Johnson published 50 Years and Other Poems.

Activism

While serving the NAACP from 1920 through 1931 Johnson started as an organizer and eventually became the first black male secretary in the organization's history. Throughout the 1920s he was one of the major inspirations and promoters of the Harlem Renaissance trying to refute condescending white criticism and helping young black authors to get published. While serving in the NAACP Johnson was involved in sparking the drive behind the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill of 1921.

Shortly before his death, Johnson supported efforts by Ignatz Waghalter, a Polish-Jewish composer who had escaped the Nazis, to establish a classical orchestra of African-American musicians. According to musical historian James Nathan Jones, the formation of the "American Negro Orchestra" represented for Johnson "the fulfillment of a dream he had had for thirty years."

James Weldon Johnson died in 1938 while on vacation in Wiscasset, Maine, when the car he was driving was hit by a train. His funeral in Harlem was attended by more than 2,000 people.[8]

Legacy

Johnson was an important contributor to the Harlem Renaissance. The Harlem Renaissance was the most important African-American cultural movement in the twentieth century if not all of American history. It brought the work of African-American writers and other artists to the general public like never before. Johnson penned the poem "Lift Every Voice and Sing" which has become the unofficial "Negro National Anthem."

In 1916, Johnson joined the staff of the NAACP. In 1920, he became general secretary of the NAACP. The NAACP became the premiere organization fighting for civil rights and equality for African-Americans in the twentieth century and beyond.

The James Weldon Johnson College Preparatory Middle School is named after him.

Honors

- On February 2, 1988, the United States Postal Service issued a 22-cent postage stamp in his honor.[9]

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed James Weldon Johnson on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[10]

Selected works

Poetry

- Lift Every Voice and Sing (1899)

- Fifty Years and Other Poems (1917)

- Go Down, Death (1926)

- God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927)

- Saint Peter Relates an Incident (1935)

- The Glory of the Day was in Her Face

- Selected Poems (1936)

Other works and collections

- The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912/1927)

- Self-Determining Haiti (1920)

- The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922)

- The Book of American Negro Spirituals (1925)

- Second Book of Negro Spirituals (1926)

- Black Manhattan (1930)

- Negro Americans, What Now? (1934)

- Along This Way (1933)

- The Selected Writings of James Weldon Johnson (1995, posthumous collection)

Notes

- ↑ https://www.npg.si.edu/exh/harmon/johnharm.htm James Weldon Johnson] National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ↑ Lift Every Voice and Sing Poetry Foundation. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ↑ James Weldon Johnson ScorSer. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ↑ James Weldon Johnson, The Literary Encyclopedia Retrieved February 19, 2009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Robert E. Fleming, James Weldon Johnson The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ↑ James Weldon Johnson, James Weldon Johnson: Writings (The Library of America, 2004, ISBN 9781931082525).

- ↑ Henry Louis Gates and Nelly Y. McKay, The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997, ISBN 9780393040012), 931.

- ↑ William L. Andrews, Frances Smith Foster, and Trudier Harris (eds.), The Oxford Companion to African American Literature, (New York: Oxford, 1997, ISBN 9780195065107), 404.

- ↑ James Weldon Johnson Smithsonian National Postal Museum.

- ↑ Molefi Kete Asante, 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2002, ISBN 1573929638).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andrews, William L., Frances Smith Foster, and Trudier Harris. The Oxford Companion to African American Literature. New York: Oxford, 1997. ISBN 9780195065107

- Asante, Molefi Kete. 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 2002. ISBN 1573929638

- Gates, Henry Louis, and Nelly Y. McKay. The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997. ISBN 9780393040012

- Johnson, James Weldon, William L. Andrews, (ed.). James Weldon Johnson: Writings. The Library of America, 2004. ISBN 9781931082525

External links

All links retrieved March 24, 2023.

- Works by James Weldon Johnson. Project Gutenberg

- James Weldon Johnson Find a Grave

- James Weldon Johnson Academy of American Poets

- James Weldon Johnson NAACP

- James Weldon Johnson Poetry Foundation

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.