Jagiellon dynasty

The Jagiellons were a royal dynasty originating from Lithuanian House of Gediminas dynasty that reigned in Central European countries (present day Lithuania, Belarus, Poland, Ukraine, Latvia, Estonia, Kaliningrad, parts of Russia, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia) between the fourteenth and sixteenth century. Members of the dynasty were Grand Dukes of Lithuania 1377–1392 and 1440–1572, kings of Poland 1386–1572, kings of Hungary 1440–1444 and 1490–1526, and kings of Bohemia 1471–1526. The dynasty was one of the most powerful families in Europe at the time.

The dynastic union between the two countries (converted into a full administrative union only in 1569) is the reason for the common appellation "Poland-Lithuania" in discussions about the area from the Late Middle Ages onwards. One Jagiellonian briefly ruled both Poland and Hungary (1440–44), and two others ruled both Bohemia (since 1471) and Hungary (1490–1526) and then continued in distaff line as the Eastern branch of the House of Habsburg. When Sigismund II Augustus died in 1572, he left no heirs and the dynasty ended. Ruling over an ethnically diverse and multi-cultural territory, the Jagiellon knit people together with common loyalty and did much to shape the idea of a common European home, transcending local identity. As patrons of learning, they did much to propagate the values of the Renaissance and their tolerant policy helped to prevent Poland from experiencing the religious conflict that waged through Europe 1560-1715.

Name

The name (other variations used in English include: Jagiellonians, Jagiellos, Jogailos) comes from Jogaila, the first Polish king of that dynasty. In Polish, the dynasty is known as Jagiellonowie (singular: Jagiellon, adjective, used of dynasty members, also patronimical form: Jagiellończyk); in Lithuanian it is called Jogailaičiai (sing.: Jogailaitis), in Belarusian Яґайлавічы (Jagajłavičy, sing.: Яґайлавіч, Jagajłavič), in Hungarian Jagellók (sing.: Jagelló), and in Czech Jagellonci (sing.: Jagellonec; adjective: Jagellonský), as well as Jagello or Jagellon (fem. Jagellonica) in Latin. In all variations of that name, the letter J should be pronounced as in "Hallelujah" (or as Y in "yes"), and G – as in "get."

Pre-dynasty background

Gediminids (Lithuanian: Gediminaičiai), the immediate predecessors of the first Jagiello, were monarchs of the medieval Lithuania with the title didysis kunigaikštis which would be translated as High King according to the contemporary perception. The later construct for its translation is Grand Duke (for its etymology, see Grand Prince). Their realm, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, chiefly meant monarch of Lithuanians and Ruthenians, and was at least half-Slavic.

Jogaila, the eponymous first Jagiello ruler, started as the Grand Duke of Lithuania. He then converted to Christianity and married the 11-year-old Jadwiga, the second of Poland's Angevin rulers, and thereby becoming himself King of Poland, founded the dynasty. At the time, he called himself King Władysław, without an ordinal number, but later historians have referred to him as Władysław II (of Poland), V (of Lithuania) or sometimes Władysław II Jagiello of Poland and Lithuania.

The rule of Piasts, the earlier Polish ruling house (c.962–1370) had ended with the death of Casimir III.

Jagiellon rulers

Jagiellons were hereditary rulers of Lithuania and Poland.

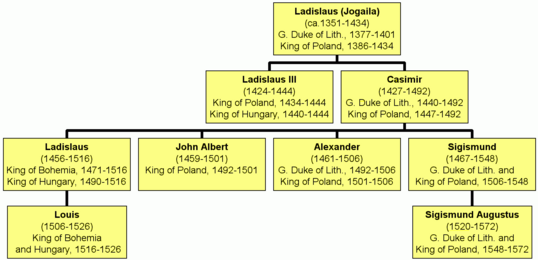

The Jagiellon rulers of Lithuania and Poland (with dates of ruling in brackets) were:

- Władysław II Jagiełło (in Lithuania 1377–1401; in Poland 1386–1434). (also known as Władysław II Jagiełło)

- Władysław III of Poland (1434–44)

- Casimir IV Jagiellon (1447–92)

- John I of Poland (1492–1501)

- Alexander of Poland (1501–05)

- Sigismund I the Old (1506–48)

- Sigismund II Augustus (1548–72) (also known as Sigismund II)

After Sigismund II Augustus, the dynasty underwent further changes. Sigismund II's heirs were his sisters, Anna Jagellonica and Catherine Jagellonica. The latter had married Duke John of Finland, who thereby from 1569 became king John III Vasa of Sweden, and they had a son, Sigismund III Vasa; as a result, the Polish branch of the Jagiellons merged with the House of Vasa, which ruled Poland from 1587 until 1668. During the interval, among others, Stephen Bathory, the husband of the childless Anna, reigned.

Jagiellon family

Bohemia and Hungary

The Jagiellons at one point also established dynastic control over the kingdoms of Bohemia (1471 onwards) and Hungary (from 1490 onwards), with Wladislaus Jagiello whom several history books call Vladisla(u)s II.

Jagiellon Kings of Bohemia and Hungary:

- Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary (Vladislaus Jagiello)

- Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia (Louis Jagiello). By Louis' sudden death in Battle of Mohács in 1526, that royal line was extinguished in male line.

- Anna of Bohemia and Hungary, Queen consort, sister of Louis. Her husband Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor was elected king of Bohemia based on her rights. He was also elected King of Hungary in dispute at first with John Zápolya and then with John II Sigismund Zápolya.

Achievements

Apart from territorial conquest, the Jagiellon were patrons of learning. The last two rulers, "encouraged every form of creative activity throughout the most dynamic period of Europe's artistic development, and they graciously allowed their subjects to do anything they wanted - except butcher each other in the name of religion." Zamoyski says that they "institutionalized a spiritual and intellectual freedom which still survives, and which steered their country away from the storm which was blowing up on the horizon," that is, the religious wars that were soon to sweep across Europe.[1]

They patronized the University of Krakow in part to train the large cadre of administrators they needed to govern their vast territory. The University was especially open to "new ideas" and it was no accident that Copernicus studied there during the Jagiellon period.[2]

Towards the end of the dynasty, the Polish throne was in practice as well as theory elective. On the one hand, the Diet or central Parliament broadened participation in governance. On the other hand, there was no strong central authority, no standing army and effectively the kings "had very little power to balance that of the landowners."[3]

A papal legate visiting the court of Sigismund II Augustus commented with admiration on his possessions and clothes. These included a hundred and eighty large caliber cannons, suits of armor of great beauty, clothes of brocade and of silk and of fur "the value of which exceeds 80 thousand gold crowns" and numerous cases of jewels.[4]

Maturity pattern

Anthropologists have noted the tendency of members of the Jagiello dynasty to marry late in life, and not procreate until older. Most of its males over the dynasty's two centuries (approximately between 1360 and 1560) managed to have their heirs only when well into their middle years.

This contrasts with the later Bourbons and Habsburg-Lorraines, prolific Roman Catholic dynasties, whose members usually started to produce offspring while still in their teens. Also, interestingly enough, those Jagiellons who continued the line, lived to ripe old ages, while those who died in their twenties or thirties, generally did not leave children. Because the average life span was relatively short in that time period, this habit of starting to produce children late axed many potential branches from the dynasty, since persons who were generally potential parents, did not start procreating until their thirties.

This was no coincidence. In this dynasty, "maturity" and willingness to settle down occurred only later in life, not in one's twenties. It has been speculated that cultural reasons may have also been co-factors. However, it has been proposed that inherited features were the chief reason. Some female-line descendants within a couple of generations showed similar tendencies, such as Charles II, Archduke of Inner Austria, and Albert VII, Archduke of Austria. However, the tendency later diminished, and after the seventeenth century, all members resumed the trait of having their children at a young age.

This tendency to bear children late, weakened the potential of the dynasty compared to others of same era. After just four generations, the dynasty went extinct in its male line. But those same four generations lasted two centuries, averaging approximately fifty years between siring each new generation:

- Algirdas (1291–1377), Ladislaus (1351–1434), Casimir IV (1427–92), Sigismund I (1467–1548) and Sigismund II (1520–72).

- Algirdas (1291–1377), Ladislaus (1351–1434), Casimir IV (1427–92), Ladislaus II (1456–1516) and Louis (1506–26)

(Generational chart: Zeroeth interval 60/60 years, first interval: 76/76 years, second interval 29/40 years, third interval 50/53 years)

| Monarch | Birth – death | Age at birth of first child to survive to adulthood |

Age at birth of first child |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ladislaus | 1351–1434 | 57 | 48 |

| Casimir IV | 1427–1492 | 29 | 29 |

| Sigismund I | 1467–1548 | 46 | 46 |

| Ladislaus II | 1456–1516 | 47 | 47 |

Sometimes, women of this dynasty married only when relatively old. Catherine Jagiellon, wife of John III of Sweden, was 11 years older than her husband, having remained unmarried into her thirties. She bore her children at ages 38, 40 and 42.

Jagiello himself was born to a father already in his fifties or sixties.

In generational terms, this was a most extraordinary dynasty.

Surviving Members

According to some members of the academic community, there are surviving, male-line descendants of the dynasty through Alexander and Helena, although this is yet to be conclusively verified.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Glomski, Jacqueline L. 2007. Patronage and humanist literature in the age of the Jagiellons: court and career in the writings of Rudolf Agricola Junior, Valentin Eck, and Leonard Cox. Erasmus studies, 16. Toronto, CA: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802093004

- Jardine, Lisa. 1996. Worldly goods: a new history of the Renaissance. New York, NY: Nan A. Talese. ISBN 9780385476843

- Roberts, J.M. 1997. The Penguin history of Europe. London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140265613

- Zamoyski, Adam. 1988. The Polish way: a thousand-year history of the Poles and their culture. New York, NY: F. Watts. ISBN 9780531150696.

External links

All links retrieved December 17, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.