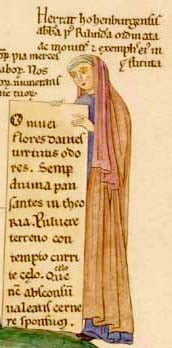

Herrad of Landsberg

Herrad of Landsberg, also Herrad of Hohenburg (c. 1130 - July 25, 1195), was a twelfth century Alsatian nun and abbess of Hohenburg Abbey in the Vosges mountains of France. She is known as the author and artist of the pictorial encyclopedia Hortus Deliciarum (The Garden of Delights), a remarkable encyclopedic text used by abbesses, nuns, and lay women alike. It brought together both past scholarship and contemporary thought that rivaled the texts used by male monasteries. Many of her ideas have been found to have a modern appreciation.

Herrad was a contemporary of several other remarkable women, including Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), Heloise (1101-1162), Eleanor of Aquitaine (1124-1204), and Claire of Assisi (1194-1253). She is considered a pioneer in the field of women's education and art.

Life in the abbey

The image of women during medieval times was limited. They were usually depicted either along the lines of the Virgin Mother of Christ or the temptress who seduces men away from God. Wealthy women could expect to be married off for their family's political gain, often dying in childbirth. Sometimes they were married off again if their aged husband died. There were few opportunities available to women for education and study because none were allowed into university.

The abbey became the safe environment where girls were able to receive education, whether as a lay student or toward the taking of vows. Many capable women chose to enter a convent in sacred service to God. There, women were often allowed to study and develop their intellect and artistic abilities in the cloistered environment of the abbey, away from the dangers of the "outside world."

An abbess was often an artist or writer herself, like Herrad of Landsberg and Hildegard of Bingen. Many were also patrons of the creativity of others. An abbess often made sure that the nuns and lay students were trained in the arts of needlework, manuscript illumination, letters, and music, as well as their devotional reading.

In the convent life of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, artists were trained by going through the alphabet, letter by letter. Most work was anonymous, as monastic life encouraged women to remain humble and simply offer their art to God. Despite the emphasis on self-denial, some nuns left little portraits of themselves in their work, or a certain mark to indicate their style.

Early life and becoming abbess

In 1147, Frederick Barbarossa appointed Relinda as abbess at the women's monastery of St. Odile at Hohenbourg, near Strausbourg in Alsace, a monastery founded possibly as early as the 600s. She was tasked to institute needed reforms, and Herrad was a nun there at that time. Barbarossa continued to support Relinda after he became emperor in 1155. Under her leadership, the monastery adopted the Augustinian Rule, and in time St. Odile became a rich and powerful monastery, a center of learning, and a school for the daughters of the area nobility.

Herrad of Landsberg was named abbess after Relinda's death in mid 1170. Little is known about Herrad's background or education. However, it is clear the her learning was broad, because she was able to produce an encyclopedic compilation of sources concerning all of salvation history, from creation to the end of the world.

Herrad provided the women under her care with the latest interpretations on the meaning of scripture, using both older theological scholars of the 1100s, such as Anselm and Bernard of Clairvaux, as well as her contemporaries, Peter Lombard and Peter Comestor. Their works formed part of the core curriculum of the new all-male schools, and drew from texts by classical and Arab writers as well. Herrad emphasized texts that reflected the newest thought on theology, biblical history, and canon law. Her book, Hortus Deliciarum (Garden of Delight), is a compendium of all the sciences studied at that time, including theology.

Hortus Deliciarum

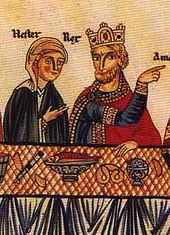

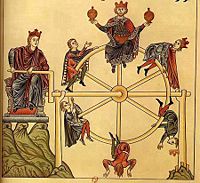

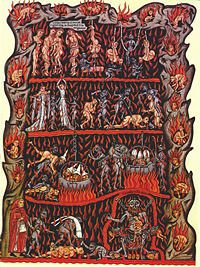

Hortus Deliciarum was begun as early as 1167, and finished in 1185, with some additions continuing until near Herrad's death in 1195. This devotional and encyclopedic teaching manual had both words and pictures to provide an advanced theological education for the learned nuns, and an aid to meditation for the less learned novices and lay students. The book also contained poetry and hymns, some of which were accompanied by musical notations, including early examples of polyphony.[1]

Hortus Deliciarum had 300 parchment leaves of folio size. In addition to the Latin texts it contained 344 illustrations, 130 of them brightly colored, full-page illuminations. Smaller illustrations adorned the pages with text. Drawings and tables were used as well. The book used both Latin and German to aid the younger readers.

Several copyists and artists worked on the book, but Herrad was without question the editor and director of Hortus Deliciarum. The work thus reflects her organization and her integration of text and illustration. Modern literary analysis indicates that probably only seven of the 67 poems were Herrad's. However, through these seven, her voice can be discerned throughout the entire collection.

In terms of its musical significance, Hortus Deliciarum is one of the first sources of polyphony originating from a nunnery. The manuscript contained at least 20 song texts, all of which were originally notated with music. Two songs survive with music intact: Primus parens hominum, a monophonic song, and a two part polyphonic work, Sol oritur occansus.[2]

While not highly original, Hortus Deliciarum shows a wide range of learning. Its chief claim to distinction lies in the illustrations which adorn the text. Many of these are symbolical representations of theological, philosophical, and literary themes. Some are historical, while others represent scenes from the actual experience of the artist. One is a collection of portraits of her sisters in religion. The technique of some of the illustrations has been very much admired and in almost every instance they show an artistic imagination which is rare in Herrad's contemporaries.

Herrad's poetry accompanies various excerpts from the writers of antiquity and pagan authors. It has the characteristic peculiar to the twelfth century: Faults of quantity, words, and constructions not sanctioned by classical usage, and peculiar turns of phrase which would hardly pass muster in a school of Latin poetry at the present time. However, the sentiment is sincere, the lines are musical and admirably adapted to the purpose for which they were intended; namely, the service of God by song. Herrad writes that she considers her community to be a congregation gathered together to serve God by singing the divine praises.

The following is an excerpt from her introduction to Hortus Deliciarum, sent to her religious superior. The bee to which she alludes was the classical symbol of the gathering and organizing of knowledge:

I make it known to your holiness, that, like a little bee inspired by God, I collected from the various flowers of sacred Scripture and philosophic writings this book, which is called the Hortus deliciarum, and I brought it together to the praise and honor of Christ and the church and for the sake of your love as if into a single sweet honeycomb. Therefore, in this very book, you ought diligently to seek pleasing food and to refresh your exhausted soul with its honeyed dewdrops…. And now as I pass dangerously through the various pathways of the sea, I ask that you may redeem me with your fruitful prayers from earthly passions and draw me upwards, together with you, into the affection of your beloved (p. 233).[3]

A song by Herrad

From Herrad's 23-stanza song, "Primus parens hominum" ("Man's first parent"), whose musical notation still exists, describes salvation history, from the creation of humanity and its fall, through the coming of Christ, to the final heavenly Jerusalem.

- Man's first parent

- As he gazed upon the heavenly light

- Was created

- Just like the company of angels,

- He was to be the consort of angels

- And to live forever.

- The serpent deceived that wretched man

- The apple that he tasted

- Was the forbidden one,

- And so that serpent conquered him

- And immediately, expelled from paradise,

- He left those heavenly courts….

- God came seeking the sheep

- That He had lost,

- And he who had given the law

- Put himself under it,

- So that for those whom he created

- He suffered a most horrible death.

- Suffering in this way with us,

- The omnipotent one

- Gave free will,

- To avoid hell,

- If we scorn vices

- And if we do good.

- Nothing will harm our soul;

- It will come into glory,

- And so we ought to love God

- And our neighbor.

- These twin precepts

- Lead to heaven. [stanzas 1-2, 16-19; pp. 245-49]

The fate of the manuscript

After having been preserved for centuries at the Hohenburg Abbey, the manuscript of Hortus Deliciarum passed into the municipal Library of Strasbourg about the time of the French Revolution. There the miniatures were copied in 1818 by Christian Moritz (or Maurice) Engelhardt; the text was copied and published by Straub and Keller, 1879-1899. Thus, although the original perished in the burning of the Library of Strasbourg during the siege of 1870 in the Franco-Prussian War, we can still form an accurate estimate of the artistic and literary value of Herrad's work.

Legacy

Herrad is seen as a pioneer of women. She possessed great artistic ability, thought, and leadership. During her time as abbess, women under her care were allowed to be educated to the best of their abilities. Not only did she leave a remarkable and beautiful historical document for future generations, but she also set a high standard of accomplishment to which other women, both secular and religious, could aspire.

The Hortus Deliciarum was a unique educational tool for women, bringing the old and new theological and scientific thought to the those within the monastery walls, allowing even the youngest novice and lay woman remarkably good education and guidance for meditation and monastic life.

Herrad's sermons can be seen as having contemporary relevance. In one, she deals the paradoxes of human life. She told the nuns to "despise the world, despise nothing; despise thyself, despise despising thyself." In her original manuscript, Herrad, sitting on a tiger skin, is seen as leading an army of "female vices" into battle against an army of "female virtues." This work both fascinated and disturbed medieval commentators.[4]

Herrad's life inspired Penelope Johnson, who highlighted Herrad's contemporary themes in her book, Equal in Monastic Profession: Religious Women in Medieval France. The book was researched from monastic documents from more than two dozen nunneries in northern France in the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries. Johnson opines that the stereotype of passive nuns living in seclusion under monastic rule is misleading. She states: "Collectively they were empowered by their communal privileges and status to think and act without many of the subordinate attitudes of secular women."

Notes

- ↑ www.amazon.ca, Amazon.com's samples of music from Hortus Deliciarum. Retrieved June, 18, 2008.

- ↑ Wikipedia, Hortus deliciarum. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ↑ Fiona Griffiths, 2007.

- ↑ J.J. Wilson and Karen Peterson, Women Artists: A Historical Survey. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brookes, Barbara, and Dorothy Page (eds.). Communities of Women: Historical Perspectives. Dunedin, N.Z.: Otago, 2002. ISBN 1877276316.

- Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. London: Thames and Hudson, 1990.

- Eckstein, Lina. Woman Under Monasticism: Chapters on Saint-Lore and Convent Life Between A.D. 500 and A.D. 1500. Cambridge University Press, 1896. ISBN 978-0543869180.

- Griffiths, Fiona J. The Garden of Delights: Reform and Renaissance for Women in the Twelfth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0812239607.

- Harris, Ann Sutherland, and Linda Nochlin. Women Artists: 1550-1950. New York: Knopf, 1977. ISBN 978-0394733265.

- Johnson, Penelope D. Equal in Monastic Profession: Religious Women in Medieval France. University Of Chicago Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0226401867.

- Schmidt, Charles. Herrade of Landsberg. Heitz und Mundel Strasbourg, 1980.

- Turner, William. "Herrad of Landsberg." In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910.

This article incorporates text from the public-domain Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913.

External links

All links retrieved July 16, 2024.

- Hortus Deliciarum www2.iath.virginia.edu

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.