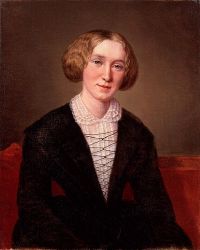

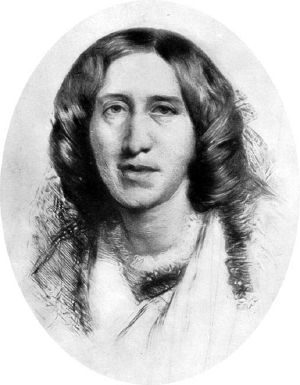

George Eliot

George Eliot is the pen name of Mary Anne Evans[1] (November 22, 1819 – December 22, 1880) an English novelist who was one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. Her novels, set largely in provincial England, are well known for their realism and psychological perspicacity. Victorian literature, particularly the novel, largely reflected the Victorian virtues of hard work, moral acuity and sober living. Eliot represented an attempt to delve beneath bourgeois society and values into the psychological depths of her characters. Eliot's novels, especially her tour de force, Middlemarch, introduced a much greater complexity to moral choice than was previously fashionable in the Victorian novel. Her great heroine, Dorothea, is faced with a series of moral choices that try her noble intentions.

Eliot used a male pen name, she said, to ensure that her works were taken seriously. At the time in England, female authors published freely under their own names, but Eliot wanted to ensure that she was not seen as merely a writer of romances. An additional factor may have been a desire to shield her private life from public scrutiny and to prevent scandals attending her relationship with the married George Henry Lewes, who couldn't divorce his wife because he had signed the birth certificate of a child born to his wife but fathered by another man. Both through her life and through the characters in her novels, Eliot demonstrates the real difficulties of living a moral life beyond mere slogans and rhetoric. Her characters are not perfect in making those choices, but her work helps the reader better understand the challenges that go with the attempt to live for a higher purpose.

Biography

Evans was the third child of Robert and Christiana Evans (née Pearson). When born, Mary Anne, often shortened to Marian, had two teenaged siblings—a half-brother and sister from her father's previous marriage to Harriet Poynton. Robert Evans was the manager of the Arbury Hall Estate for the Newdigate family in Warwickshire, and Mary Anne was born on the estate at South Farm, Arbury, near Nuneaton. In early 1820 the family moved to a house named Griff, part way between Nuneaton and Coventry.

The young Mary Anne was obviously intelligent, and due to her father's important role on the estate, she was allowed access to the library of Arbury Hall, which greatly aided her education and breadth of learning. Her classical education left its mark; Christopher Stray has observed that "George Eliot's novels draw heavily on Greek literature (only one of her books can be printed without the use of a Greek font), and her themes are often influenced by Greek tragedy" (Classics Transformed, 81). Her frequent visits also allowed her to contrast the relative luxury in which the local landowner lived with the lives of the much poorer people on the estate; the treatment of parallel lives would reappear in many of her works. The other important early influence in her life was religion. She was brought up within a narrow low church Anglican family, but at that time the Midlands was an area with many religious dissenters, and those beliefs formed part of her education. She boarded at schools in Attleborough, Nuneaton and Coventry. At Nuneaton she was taught by the evangelical Maria Lewis—to whom her earliest surviving letters are addressed—while at the Coventry school she received instruction from Baptist sisters.

In 1836 her mother died, so Evans returned home to act as housekeeper, but she continued her education with a private tutor and advice from Maria Lewis. It was while she was acting as the family's housekeeper that she invented the Marmalade Brompton cake. She passed the recipe to a local baker who produced it on a commercial basis and, for a while, it was the most popular cake in England. When she was 21, her brother Isaac married and took over the family home, so Evans and her father moved to Foleshill near Coventry.

The closeness to Coventry society brought new influences, most notably those of Charles and Cara Bray. Charles Bray had become rich as a ribbon manufacturer who used his wealth in building schools and other philanthropic causes. He was a freethinker in religious matters, a progressive in politics, and his home Rosehill was a haven for people who held and debated radical views. The people whom the young woman met at the Brays' house included Robert Owen, Herbert Spencer, Harriet Martineau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Through this society, Evans was introduced to more liberal theologies, many of which cast doubt on the supernatural elements of Biblical stories, and she stopped going to church. This caused a rift between her and her family, with her father threatening to throw her out. Relenting, she respectably attended church and continued to keep house for him until his death in 1849. Her first major literary work was the translation of David Strauss' Life of Jesus (1846), which she completed after it was begun by another member of the Rosehill circle.

Before her father's death, Evans traveled to Switzerland with the Brays. On her return she moved to London with the intent of becoming a writer and calling herself Marian Evans. She stayed at the house of John Chapman, the radical publisher whom she had met at Rosehill and who had printed her translation of Strauss. Chapman had recently bought the campaigning, left-wing journal The Westminster Review, and Evans became its assistant editor in 1851. Although Chapman was the named editor, it was Evans who did much of the work in running the journal for the next three years, contributing many essays and reviews.

—Henry James

Women writers were not uncommon at the time, but Evans’ role at the head of a literary enterprise was. Even the sight of an unmarried young woman mixing with the predominantly male society of London at that time was unusual, even scandalous to some. Although clearly strong-minded, she was frequently sensitive, depressed, and crippled by self-doubts. She was well aware of her ill-favored appearance, but it did not stop her from making embarrassing emotional attachments, including her employer, the married Chapman, and Herbert Spencer. Yet another highly inappropriate attraction would be much more successful and beneficial for Evans.

The philosopher and critic George Henry Lewes met Marian Evans in 1851, and by 1854 they had decided to live together. Lewes was married to Agnes Jervis, but they had decided to have an open marriage, and in addition to having three children together, Agnes also had had several children with another man. As he was listed on the birth certificate as the father of one of these children despite knowing this to be false, and since he was therefore complicit in adultery, he was not able to divorce Agnes. In 1854 Lewes and Evans traveled to Weimar and Berlin together for the purposes of research. Before going to Germany, Marian continued her interest in theological work with a translation of Ludwig Feuerbach's Essence of Christianity and while abroad she wrote essays and worked upon her translation of Baruch Spinoza's Ethics, which she would never complete.

The trip to Germany also doubled as a honeymoon as they were now effectively married with Evans now calling herself Marian Evans Lewes. It was not unusual for men in Victorian society to have mistresses, including both Charles Bray and John Chapman. What was scandalous was the Lewes' open admission of the relationship. On their return to England, they lived apart from the literary society of London, both shunning and being shunned in equal measure. While continuing to contribute pieces to the Westminster Review, Evans Lewes had resolved to become a novelist, and she set out a manifesto for herself in one of her last essays for the Review: “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists.” The essay criticized the trivial and ridiculous plots of contemporary fiction by women. In other essays she praised the realism of novels written in Europe at the time, and an emphasis on realistic story-telling would be clear throughout her subsequent fiction. She also adopted a new "nom de plume," the one for which she would become best known: George Eliot. This masculine name was partly to distance herself from the lady writers of silly novels, but it also quietly hid the tricky subject of her marital status.

In 1857 Amos Barton, the first of the Scenes of Clerical Life, was published in Blackwood's Magazine and, along with the other Scenes, was well received. Her first complete novel, published in 1859, was Adam Bede and was an instant success, but it prompted an intense interest in who this new author was. The Scenes of Clerical Life was widely believed to have been written by a country parson or perhaps the wife of a parson.

With the release of the incredibly popular Adam Bede, the speculation increased markedly, and there was even a pretender to the authorship, Joseph Liggins. In the end, the real George Eliot stepped forward: Marian Evans Lewes admitted she was the author. The revelations about Eliot's private life surprised and shocked many of her admiring readers, but it apparently did not affect her popularity as a novelist. Eliot's relationship with Lewes gave her the encouragement and stability she needed to write fiction and ease her self-doubts, but it would take time before they were accepted into polite society. Acceptance was finally confirmed in 1877, when they were introduced to Princess Louise, the daughter of Queen Victoria, who was a reader of George Eliot's novels.

After the popularity of Adam Bede, she continued to write popular novels for the next fifteen years. Her last novel was Daniel Deronda in 1876, after which she and Lewes moved to Witley, Surrey, but by this time Lewes' health was failing and he died two years later on November 30, 1878. Eliot spent the next two years editing Lewes' final work Life and Mind for publication, and she found solace with John Walter Cross, an American banker whose mother had recently died.

On May 6, 1880 Eliot courted controversy once more by marrying a man twenty years younger than herself, and again changing her name, this time to Mary Ann Cross. The legal marriage at least pleased her brother Isaac, who sent his congratulations after breaking off relations with his sister when she had begun to live with Lewes. John Cross was a rather unstable character, and apparently jumped or fell from their hotel balcony into the Grand Canal in Venice during their honeymoon. Cross survived and they returned to England. The couple moved to a new house in Chelsea but Eliot fell ill with a throat infection. Coupled with the kidney disease she had been afflicted with for the past few years, the infection led to her death on the December 22, 1880, at the age of 61.

She is buried in Highgate Cemetery (East), Highgate, London in the area reserved for religious dissenters, next to George Henry Lewes.

Literary assessment

Eliot's most famous work, Middlemarch, is a turning point in the history of the novel. Making masterful use of a counterpointed plot, Eliot presents the stories of a number of denizens of a small English town on the eve of the Reform Bill of 1832. The main characters, Dorothea Brooke and Tertius Lydgate, long for exceptional lives but are powerfully constrained both by their own unrealistic expectations and by a conservative society. The novel is notable for its deep psychological insight and sophisticated character portraits.

Throughout her career, Eliot wrote with a politically astute pen. From Adam Bede to The Mill on the Floss and the frequently-read Silas Marner, Eliot presented the cases of social outsiders and small-town persecution. No author since Jane Austen had been as socially conscious and as sharp in pointing out the hypocrisy of the country squires. Felix Holt, the Radical and The Legend of Jubal were overtly political novels, and political crisis is at the heart of Middlemarch. Readers in the Victorian era particularly praised her books for their depictions of rural society, for which she drew on her own early experiences, sharing with Wordsworth the belief that there was much interest and importance in the mundane details of ordinary country lives.

Eliot did not, however, confine herself to her bucolic roots. Romola, an historical novel set in late fifteenth-century Florence and touching on the lives of several real persons such as the priest Girolamo Savonarola, displays her wider reading and interests. In The Spanish Gypsy, Eliot made a foray into verse, creating a work whose initial popularity has not endured.

The religious elements in her fiction also owe much to her upbringing, with the experiences of Maggie Tulliver from The Mill on the Floss sharing many similarities with the young Mary Anne Evans' own development. When Silas Marner is persuaded that his alienation from the church means also his alienation from society, the author's life is again mirrored with her refusal to attend church. She was at her most autobiographical in Looking Backwards, part of her final printed work Impressions of Theophrastus Such. By the time of Daniel Deronda, Eliot's sales were falling off, and she faded from public view to some degree. This was not helped by the biography written by her husband after her death, which portrayed a wonderful, almost saintly woman totally at odds with scandalous life they knew she had led. In the twentieth century she was championed by a new breed of critics; most notably by Virginia Woolf, who called Middlemarch "one of the few English novels written for grown-up people." The various film and television adaptations of Eliot's books have re-introduced her to the wider-reading public.

As an author, Eliot was not only very successful in sales, but she was, and remains, one of the most widely praised for her style and clarity of thought. Eliot's sentence structures are clear, patient, and well balanced, and she mixes plain statement and unsettling irony with rare poise. Her commentaries are never without sympathy for the characters, and she never stoops to being arch or flippant with the emotions in her stories. Villains, heroines and bystanders are all presented with awareness and full motivation.

Works

Novels

- Adam Bede, 1859

- The Mill on the Floss, 1860

- Silas Marner, 1861

- Romola, 1863

- Felix Holt, the Radical, 1866

- Middlemarch, 1871-1872

- Daniel Deronda, 1876

Other works

- Translation of "The Life of Jesus Critically Examined" by David Strauss, 1846

- Scenes Of Clerical Life, 1858

- Amos Barton

- Mr Gilfil's Love Story

- Janet's Repentance

- The Lifted Veil, 1859

- Impressions of Theophrastus Such, 1879

Poetry

Poems by George Eliot include:

- The Spanish Gypsy (a dramatic poem) 1868

- Agatha, 1869

- Armgart, 1871

- Stradivarius, 1873

- The Legend of Jubal, 1874

- Arion, 1874

- A Minor Prophet, 1874

- A College Breakfast Party, 1879

- The Death of Moses, 1879

Notes

- ↑ Baptized Mary Anne Evans in 1819. At the wedding of her sister in 1837, she signed her name Mary Ann Evans.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Haight, Gordon S. George Eliot: A Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968. ISBN 0198116667

- Haight, Gordon S. (ed.). George Eliot: Letters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1954. ISBN 0300010885

- Jenkins, Lucien. Collected Poems of George Eliot. London: Skoob Books Publishing, 1989. ISBN 1871438357

- Uglow, Jennifer. George Eliot. London: Virago, 1987. ISBN 0394753593

Context and background

- Beer, Gillian. Darwin's Plots: Evolutionary Narrative in Darwin, George Eliot and Nineteenth-Century Fiction. Cambridge University Press, 2000 (original 1983). ISBN 0521783925

- Beer, Gillian. George Eliot. Prentice Hall / Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1986. ISBN 071080511X

- Chapman, Raymond. The Sense of the Past in Victorian Literature. London: CroomHelm, 1986. ISBN 0709934416

- Cosslett, Tess. The 'Scientific Movement' and Victorian Literature. Brighton: Harvester, 1982. ISBN 0312702981

- Gilbert, Sandra M., and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000 (original 1979). ISBN 0300084587

- Hughes, Kathryn. George Eliot: The Last Victorian. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1998. ISBN 0374161380

- Jay, Elisabeth. The Religion of the Heart: Anglican Evangelicalism and the Nineteenth-Century Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979. ISBN 0198120923

- Pinney, Thomas (ed.). Essays of George Eliot. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1963. ISBN 0231026196

- Shuttleworth, Sally. George Eliot and Nineteenth-Century Science: The Make-Believe of a Beginning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 0521257867

- Willey, Basil. Nineteenth-Century Studies: Coleridge to Matthew Arnold London: Chatto & Windus, 1973 (original 1964). ISBN 0140217096

- Williams, Raymond. The Country and the City. Oxford University Press, 1975. ISBN 0195198107

Critical studies

- Alley, Henry. The Quest for Anonymity: The Novels of George Eliot. University of Delaware Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0874136210

- Ashton, Rosemary. George Eliot. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997 (original 1983). ISBN 978-0713991949

- Beaty, Jerome. 'Middlemarch' from Notebook to Novel: A Study of George Eliot's Creative Method. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1981 (original 1960). ISBN 978-0313224126

- Carroll, David (ed.). George Eliot: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1971. ISBN 978-0710069368

- Daiches, David. George Eliot: Middlemarch. London: Edward Arnold, 1963. ISBN 978-0713150735

- Dentith, Simon. George Eliot. Brighton: Harvester, 1986. ISBN 978-0710805980

- Garrett, Peter K. The Victorian Multiplot Novel: Studies in Dialogical Form. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1980. ISBN 978-0300024036

- Graver, Suzanne. George Eliot and Community: A Study in Social Theory and Fictional Form. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0520048027

- Harvey, W. J. The Art of George Eliot. Praeger, 1978 (original 1961). ISBN 978-0313202674

- Kettle, Arnold. An Introduction to the English Novel, vol. I. London: Hutchinson, 1967 (original 1951). ISBN 0090485432

- Leavis, F. R. The Great Tradition. London: Chatto & Windus, 1948. ISBN 978-0814702536

- Neale, Catherine. Middlemarch: Penguin Critical Studies. London: Penguin, 1989. ISBN 978-0140771732

- Swinden, Patrick. George Eliot: Middlemarch. London: Macmillan, 1972. ISBN 978-0333058381

External links

All links retrieved May 15, 2024.

- George Eliot: An Overview – VictorianWeb

- George Eliot – Literary Encyclopedia

- Works by George Eliot. Project Gutenberg

- George Eliot Quotations at LitQuotes

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.