French Campaign against Korea, 1866

| French campaign against Korea, 1866 (The byeong-in yang-yo) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Combatants | |||||||||

| Joseon Dynasty Korea |

France | ||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||

| Korea: King Gojong Daewongun |

France: Pierre-Gustave Roze | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Korea: unknown |

France: 150 | ||||||||

| Casualties | |||||||||

| Korea: Unknown |

France: 10 | ||||||||

The French campaign against Korea of 1866, known as Byeonginyangyo (Korean: 병인양요, Western Disturbance of the byeong-in year (1866)), refers to the French occupation of Ganghwa Island in retaliation for the execution of French Jesuit priests and thousands of the converts. The campaign, the first armed encounter between Korea and a western power, lasted nearly six weeks. The French withdrew, leaving the Korean government with a false sense of security that Korea withstand imperialistic designs of their neighbors without modernizing. The Daewongun would make the mistaken judgment that a show of force would keep foreign ideas (i.e., Christianity) and foreign powers at bay. He intended to maintain Korea as a Confucian nation with strong ties to China at all costs.

| French Campaign against Korea, 1866 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Background

Though Joseon Dynasty Korea maintained a policy of isolation from the outside world (save for tribute intercourse with China and occasional trading with Japan through Tsushima), the day arrived that Korea had to open its doors. Catholicism had spread to China as early as the sixteenth century. Through Korean tribute missions to the Qing court in the eighteenth century, Christianity began to enter Korea and by the late eighteenth century Christianity began to take root in Korea. In the mid-nineteenth century the first Catholic missionaries began to enter Korea from China and France.

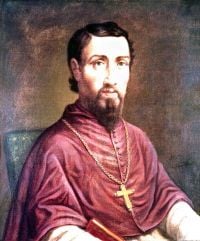

Prohibitions against Christianity forced missionaries to enter and practice underground, entering by way of the Korean border with Manchuria or the Yellow Sea. The first Jesuit missionaries from France arrived in Korea in the 1840s to shepherd a growing Korean flock. Bishop Siméon-François Berneux, appointed in 1856 as head of the infant Korean Catholic church, estimated in 1859 that the number of Korean faithful had reached nearly 17,000.[1]

At first the Korean court ignored the missionaries. That attitude changed abruptly with the enthronement of King Gojong in 1864 and the regency of the Daewongun.

During the Joseon dynasty, regency for a minor went to the ranking dowager queen, in this case the fiercely conservative mother of the previous crown prince, who had died before he could ascend the throne. The new king’s father, Yi Ha-ung, a wily and ambitious man in his early forties, received the title of Daewongun, or “Prince of the Great Court.” The Daewongun quickly seized the initiative and began to control state policy. He became one of the most ruthless and intriguing leaders of the 500 year old Joseon dynasty. The Daewongun immediately set out on a dual campaign of consolidating all royal power in his hands and exterminating any cutting off any influence from abroad. By the time the Daewongun assumed de facto control of the government in 1864, twelve French Jesuit priests living and preaching in Korea, serving an estimated 23,000 native Korean converts.[2]

In January, 1866 Russian ships appeared on the east coast of Korea demanding trading and residency rights in what seemed an echo of the demands made on China by other western powers. Native Korean Christians with connections at court, saw an opportunity to advance their cause. They promoted Bishop Berneux as the person to negotiate an alliance between France and Korea to repel the Russian advances. The Daewongun seemed to agree with the idea as ruse to bring the head of the Korean Catholic Church out of his hiding place. He summoned Berneux to the capital in February 1866, seized and executed him. He then began a roundup of the other French Catholic priests and native converts.

The Daewongun's treachery derived from the belief that Christianity opened the door to China's demise with the Second Opium War. He reasoned that eradicating Christianity would enhance Korea's security. He most likely reflected that the Taiping Rebellion of 1865 in China, which had been infused with western Christian doctrines, could happen in Korea. In addition, a powerful yet minor faction in the royal court practiced and promoted Christianity. He intended to curtail or destroy their influence as well.

The Daewongun's police action resulted in the capture and execution of nine French missionaries. An impossible to determine, because of a lack of records, number of native Korean Catholics suffered gruesome martyrdom. Korean Catholics estimate the number of martyred at 10,000, which is the number for infinity in Korean,"It is estimated than 10,000 were killed within a few months" [3] many being executed a place called Jeoldu-san in Seoul on the banks of the Han River. Bishop Berneux was tortured and then beheaded on March 7, 1866.[4] In late June 1866 one of the three surviving French missionaries, Father Felix-Claire Ridel, managed to escape via a fishing vessel and make his way to Tianjin, China in early July 1866. Fortuitously, the commander of the French Far Eastern Squadron, Rear Admiral Pierre-Gustave Roze harbored in Tianjin at the time of Ridel‘s arrival. Hearing of the massacre, Roze determined to launch a punitive expedition. The acting French consul in Peking, Henry de Bellonet, strongly supported the expedition.

The French had compelling reasons to launch a punitive expedition. Violence against Christian missionaries and converts in the Chinese interior, which after the Second Opium War in 1860 had been opened up to westerners, increased. Since Korea had vassal status, diplomatic and military authorities viewed the massacre of westerners and Christians in Korea as an extension of the anti-western outbreaks in China. Key French diplomats believe a firm response to such acts of violence necessary to ensure the safety of their nationals. While the acting French consul in Peking took up a diplomatic initiative with Chinese authorities, Rear Admiral Roze made his own military preparations for a campaign against Korea.

Preliminaries (September 18 - October 3, 1866)

The almost utter absence of any detailed information on Korea, including any navigational charts, slowed the French diplomatic and naval authorities in China eager to launch an expedition. Prior to the actual expedition Rear Admiral Roze decided to undertake a smaller surveying expedition along the Korean coast, especially along the waterway leading to the Korean capital of Seoul. He performed that survey in late September and early October 1866. Those preliminaries resulted in some rudimentary navigational charts of the waters around Ganghwa Island and the Han River leading to Seoul. The treacherous nature of the waters convinced Roze that any movement against the fortified Korean capital with his limited fleet and with his large hulled vessels would fail. Instead he opted to seize and occupy Ganghwa Island, which commanded the entrance to the Han River. He hoped to blockade the waterway to the capital during the harvest season, thereby giving him leverage to force demands of reparitions on the Korean court.

The nature those demands have never been made public. In Peking, the French consul Bellonet had made severe (and as it turned out unofficial) demands that the Korean monarch forfeit his crown and cede sovereignty to France. Such a stance stood at odds with Rear Admiral Roze's goal forcing reparitions. In any case, the Bellonet demands never received official endorsement from the French government of Napoleon III. Bellonet received a reprimand for talking in public unoffically.[5]

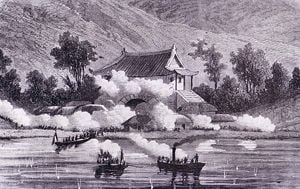

Expedition (October 11 - November 12, 1866)

On October 11, Admiral Roze left Tchefou with the frigate La Guerrière, two avisos, two gunboats and a corvette. A group of 170 French marines landed on Ganghwa island and took the fortress which controlled the Han river. The French offensive met with stiff resistance from the troops of General Yi Yong-Hui, whom Roze sent several unsuccessful letters demanding reparation. The French bombarding the area, and then sailed up the Han river towards Seoul. The French marines seized several fortified positions, as well as booty such as flags, cannons, 8,000 muskets, twenty boxes of silver ingots, and various lacquer works, jades, manuscripts and paintings.

Roze sent a letter demanding the release of two French missionaries still imprisoned. After receiving no reply, Roze bombarded the palace and the adjoining official buildings on November 11. The Daewongun released the two missionaries.[6]

Obtaining satisfaction, Roze left Seoul and sailed down the Han river. Twenty-four hours later, he gave the order conclude the expedition, destroying property while departing. Roze had accomplished what he could with his limited forces, hoping that he had made the Royal court think twice about killing French nationals, missionaries, and Korean native Catholics:

- "The expedition I just accomplished, however modest as it is, may have prepared the ground for a more serious one if deemed necessary,… The expedition deeply shocked the Korean Nation, by showing her claimed invulnerability was but an illusion. Lastly, the destruction of one of the avenues of Seoul, and the considerable losses suffered by the Korean government should render it more cautious in the future. The objective I had fixed to myself is thus fully accomplished, and the murder of our missionaries has been avenged." November 15 report by Admiral Roze: "L'expédition que je viens de faire, si modeste qu'elle soit, en aura préparé une plus sérieuse si elle est jugée nécessaire,…. Elle aura d'ailleurs profondément frappé l'esprit de la Nation Coréenne en lui prouvant que sa prétendue invulnérabilité n'était que chimérique. Enfin la destruction d'un des boulevards de Seoul et la perte considérable que nous avons fait éprouver au gouvernement coréen ne peuvent manquer de le rendre plus circonspect. Le but que je m'étais fixé est donc complètement rempli et le meurtre de nos missionaries a été vengé" [7]

The European residents in China had hoped that Korea would pay a greater price, demanding a larger expedition for the following Spring, but that never happened. After the expedition, Roze and his fleet sailed to Japan, where they arrived in time to welcome the first French Military Mission to Japan (1867-1868) in the harbor of Yokohama on January 13, 1867.

Epilogue

Less than a year later, in August 1867, an American ship General Sherman foundered on the coast of Korea. Koreans massacred some of the sailors. When the United States could not obtain reparations, they discussed mounting a combined operation with France. The USA abandoned the expedition due to the low interest in Korea at that time. A punitive expedition took place happened later, in 1871, with the United States Korean expedition.

The Korean government agreed to open the country in 1877 when a large fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy under the orders of Kuroda Kiyotaka, lead to the signing of the Treaty of Ganghwa.

Notes

- ↑ Charles Dallet, 1970. "A history of the church in Korea." Human relations area files, 49. (New Haven, Conn: Human Relations Area Files. OCLC: 32480363), 452. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ↑ Daniel C. Kane. “Heroic Defense of the Hermit Kingdom.” Military History Quarterly 2(Summer 2000): 38-47. (1999), 2.

- ↑ Léon C. Rochotte. "La campagne de l'amiral Pierre-Gustave Roze" Source

- ↑ Source"Newsletter of the District of Asia," (Jan-Jun 2001) "A Korean Martyr for the Society of St Pius X: St Siméon François Berneux, Bishop and Martyr, 4th Apostolic Vicar of Korea (1814 – 1866). Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ↑ Daniel C. Kane. “Bellonet and Roze: Overzealous Servants of Empire and the 1866 French Attack on Korea.” Korean Studies 23 (1999), 20

- ↑ Léon Rochotte. "Le résultat est immédiat: les deux missionaries sont remis à l'Amiral." "La Corée 5.000 ans d'Histoire en raccourci" Net4War website [1] (in French) Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ↑ Ibid., 4[2].Retrieved September 29, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Books

- Choe, Ching Young. "The rule of the Taewŏnʼgun, 1864-1873; restoration in Yi Korea." Harvard East Asian monographs, 45. Cambridge: East Asian Research Center, Harvard University; distributed by Harvard University Press, 1972. ISBN 978-0674780309

- Dallet, Charles. A history of the church in Korea. Human relations area files, 49. New Haven, Conn: Human Relations Area Files, 1970. OCLC 32480363.

- Kane, Daniel C. Korea, a Century of Change. Juergen Kleiner (ed.). Singapore: World Scientific, 2001.

- Kim, Yong-gu. The five years' crisis, 1866-1871: Korea in the maelstrom of western imperialism. Inchʻŏn, Korea: Circle, 2001. ISBN 978-8989443018

Articles

- Choi, Soo Bok. “The French Jesuit Mission in Korea, 1827-1866.” North Dakota Quarterly 36 (Summer 1968): 17-29.

- Kane, Daniel C. “Bellonet and Roze: Overzealous Servants of Empire and the 1866 French Attack on Korea.” Korean Studies 23 (1999): 1-23.

- Kane, Daniel C. “Heroic Defense of the Hermit Kingdom.” Military History Quarterly (2000): 38-47.

- Orange, Marc. “L’Expédition de l’Amiral Roze en Corée.” Revue de Corée 30 (1976): 44-84.

External links

All links retrieved April 11, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.