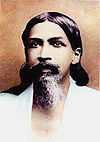

Dayananda Saraswati

Swami Dayananda Saraswati (सà¥âवामॠदयाननà¥âद सरसà¥âवतà¥) (1824 - 1883) was an important Hindu religious scholar born in Gujarat, India. He is best known as the founder of the Arya Samaj "Society of Nobles," a great Hindu reform movement, founded in 1875. He was a sanyasi (one who has renounced all worldly possessions and relations) from his boyhood. He was an original scholar, who believed in the infallible authority of the Vedas. Dayananda advocated the doctrine of karma, skepticism in dogma, and emphasized the ideals of brahmacharya (celibacy and devotion to God). The Theosophical Society and the Arya Samaj were united for a certain time under the name Theosophical Society of the Arya Samaj.

Dayananda was an important Hindu reformist whose views did much to promote gender-equality, democracy, education, as well as a new confidence in India's cultural past and future capabilities. In some respects, he qualifies as an architect of modern India as am emerging scientific and technological power. Aspects of his views impacted negatively on inter-religious relations, however, and contributed to extreme forms of Hindu nationalism which denies non-Hindus their complete civil rights. Yet, in his own day, when he spoke of the superiority of Hindu culture and religion, he was doing so in defense of what Europeans in India had insulted and denigrated. A consequence of assuming racial, cultural, or religious superiority over others is that they retaliate, and reverse what is said about them. The Arya Samaj is now a worldwide movement.

Upbringing

Born in Kathiawi, Gujerat, Dayananda's parents were wealthy members of the priestly class, the Brahmins (or Brahmans). Although raised as an observant Hindu, in his late teens Dayananda turned to a detailed study of the Vedas, convinced that some contemporary practices, such as the veneration of images (murtis) was a corruption of pure, original Hinduism. His inquiries were prompted by a family visit to a temple for overnight worship, when he stayed up waiting for God to appear to accept the offerings made to image of the God Shiva. While everyone else slept, Dayananda saw mice eating the offerings kept for the God. Utterly surprised, he wondered how a God, who cannot even protect his own "offerings," would protect humanity. He later argued with his father that they should not worship such a helpless God. He then started pondering the meaning of life and death, and asking questions that worried his parents.

Quest for liberation

In 1845, he declared that he was starting a quest for enlightenment, or for liberation (moksha), left home and started to denounce image-veneration. His parents had decided to marry him off in his early teens (common in nineteenth century India), so instead Dayananda chose to become a wandering monk. He learned Panini's Grammar to understand Sanskrit texts. After wandering in search of guidance for over two decades, he found Swami Virjananda (1779-1868) near Mathura who became his guru. The guru told him to throw away all his books in the river and focus only on the Vedas. Dayananda stayed under Swami Virjananda's tutelage for two and a half years. After finishing his education, Virjananda asked him to spread the concepts of the Vedas in society as his gurudakshina ("tuition-dues"), predicting that he would revive Hinduism.

Reforming Hinduism

Dayananda set about this difficult task with dedication, despite attempts on his life. He traveled the country challenging religious scholars and priests of the day to discussions and won repeatedly on the strength of his arguments. He believed that Hinduism had been corrupted by divergence from the founding principles of the Vedas and misled by the priesthood for the priests' self-aggrandizement. Hindu priests discouraged common folk from reading Vedic scriptures and encouraged rituals (such as bathing in the Ganges and feeding of priests on anniversaries) which Dayananda pronounced as superstitions or self-serving.

He also considered certain aspects of European civilization to be positive, such as democracy and its emphasis on commerce, although he did not find Christianity at all attractive, or European cultural arrogance, which he disliked intensely. In some respects, his ideas were a reaction to Western criticism of Hinduism as superstitious idolatry. He may also have been influenced by Ram Mohan Roy, whose version of Hinduism also repudiated image-veneration. He knew Roy's leading disciple, Debendranath Tagore and for a while had contemplated joining the Brahmo Samaj but for him the Vedas were too central

In 1869, Dayananda set up his first Vedic School, dedicated to teaching Vedic values to the fifty students who registered during the first year. Two other schools followed by 1873. In 1875, he founded the Arya Samaj in 1875, which spearheaded what later became known as a nationalist movement within Hinduism. The term "fundamentalist" has also been used with reference to this strand of the Hindu religion.

The Arya Samaj

The Arya Samaj unequivocally condemns idol-veneration, animal sacrifices, ancestor worship, pilgrimages, priestcraft, offerings made in temples, the caste system, untouchability, child marriages, and discrimination against women on the grounds that all these lacked Vedic sanction. The Arya Samaj discourages dogma and symbolism and encourages skepticism in beliefs that run contrary to common sense and logic. To many people, the Arya Samaj aims to be a "universal church" based on the authority of the Vedas. Dayananda taught that the Vedas are rational and contain universal principles. Fellow reformer Vivekananda also stressed the universal nature of the principles contained in Hindu thought, but for him the Ultimate was trans-personal, while Dayananda believed in a personal deity.

Among Swami Dayananda's immense contributions is his championing of the equal rights of womenâsuch as their right to education and reading of Indian scripturesâand his translation of the Vedas from Sanskrit to Hindi so that the common person may be able to read the Vedas. The Arya Samaj is rare in Hinduism in its acceptance of women as leaders in prayer meetings and preaching. Dayananda promoted the idea of marriage by choice, strongly supported education, pride in India's past, in her culture as well as in her future capabilities. Indeed, he taught that Hinduism is the most rational religion and that the ancient Vedas are the source not only of spiritual truth but also of scientific knowledge. This stimulated a new interest in India's history and ancient disciples of medicine and science. Dayananda saw Indian civilization as superior, which some later developed into a type of nationalism that looked on non-Hindus as disloyal.

For several years (1879-1881), Dayananda was courted by the Theosophist, Helena Blavatsky, and Henry Steel Olcott, who were interested in a merger which was temporarily in place. However, their idea of the Ultimate Reality as impersonal did not find favor with Dayananda, for whom God is a person, and the organizations parted.

Dayananda's views on other religions

Far from borrowing concepts from other religions, as Raja Ram Mohan Roy had done, Swami Dayananda was quite critical of Islam and Christianity as may be seen in his book, Satyartha Prakash. He was against what he considered to be the corruption of the pure faith in his own country. Unlike many other reform movements within Hinduism, the Arya Samaj's appeal was addressed not only to the educated few in India, but to the world as a whole, as evidenced in the sixth of ten principle of the Arya Samaj.[1]

Arya Samaj, like a number of other modern Hindu movements, allows and encourages converts to Hinduism, since Dayananda held Hinduism to be based on "universal and all-embracing principles" and therefore to be "true." "I hold that the four Vedas," he wrote, "the repository of Knowledge and Religious Truths- are the Word of God â¦They are absolutely free from error and are an authority unto themselves."[2] In contrast, the Gospels are silly, and "no educated man" could believe in their content, which contradicted nature and reason.

Christians go about saying "Come, embrace my religion, get your sins forgiven and be saved" but "All this is untrue, since had Christ possessed the power of having sins remitted, instilling faith in others and purifying them, why would he not have freed his disciples from sin, made them faithful and pure," citing Matthew 17:17.[3] The claim that Jesus is the only way to God is fraudulent, since "God does not stand in need of any mediator," citing John 14: 6-7. In fact, one of the aims of the Arya Samaj was to re-convert Sikhs, Muslims and Christians. Sikhs were regarded as Hindus with a distinct way of worship. Some Gurdwaras actually fell under the control of the Arya Samaj, which led to the creation of a new Sikh organization to regain control of Sikh institutions. As the political influence of the movement grew, this attitude towards non-Hindu Indian's had a negative impact on their treatment, inciting such an event as the 1992 destruction of the Mosque at Ayodhia. There and elsewhere, Muslims were accused of violating sacred Hindu sites by bulding Mosques where Temples had previously stood. The Samaj has been criticized for aggressive intolerance against other religions.<see>Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Arya Samaj.</ref>

However, given the hostility expressed by many Christian missionaries and colonial officials in India towards the Hindu religion, which they often held in open contempt, what Dayananda did was to reverse their attitude and give such people a taste of their own medicine.

Support for democracy

He was the among the first great Indian stalwarts who popularized the concept of Swarajâright to self-determination vested in an individual, when India was ruled by the British. His philosophy inspired nationalists in the mutiny of 1857 (a fact that is less known), as well as champions such as Lala Lajpat Rai and Bhagat Singh. Dayananda's Vedic message was to emphasize respect and reverence for other human beings, supported by the Vedic notion of the divine nature of the individualâdivine because the body was the temple where the human essence(soul or "Atma") could possibly interface with the creator ("ParamAtma"). In the 10 principles of the Arya Samaj, he enshrined the idea that "All actions should be performed with the prime objective of benefiting mankind" as opposed to following dogmatic rituals or revering idols and symbols. In his own life, he interpreted Moksha to be a lower calling (due to its benefit to one individual) than the calling to emancipate others. The Arya Samaj is itself democratically organized. Local societies send delegates to regional societies, which in turn send them to the all India Samaj.

Death

Dayananda's ideas cost him his life. He was poisoned in 1883, while a guest of the Maharaja of Jodhpur. On his deathbed, he forgave his poisoner, the Maharaja's cook, and actually gave him money to flee the king's anger.

Legacy

The Arya Samaj remains a vigorous movement in India, where it has links with several other organizations including some political parties. Dayananda and the Arya Samaj provide the ideological underpinnings of the Hindutva movement of the twentieth century. Ruthven regards his "elevation of the Vedas to the sum of human knowledge, along with his myth of the Aryavartic kings" as religious fundamentalism, but considers its consequences as nationalistic, since "Hindutva secularizes Hinduism by sacralizing the nation." Dayananda's back-to-the-Vedas message influenced many thinkers.[4] The Hindutva concept considers that only Hindus can properly be considered India. Organizatuions such as the RSS (the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) and the BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party]] were influenced by the Arya Samaj.

Dayananda also influenced Sri Aurobindo, who decided to look for hidden psychological meanings in the Vedas.[5] Dayananda's legacy may have had a negative influence in encouraging Hindu nationalism that denies the full rights of non-Hindus. On the other hand, he was a strong democrat and an advocate of women's rights. His championship of Indian culture, and his confidence in India's future ability to contribute to science, did much to stimulate India's post-colonial development as a leading nation in the area of technology especially.

Works

Dayananda Saraswati wrote more than 60 works in all, including a 14 volume explanation of the six Vedangas, an incomplete commentary on the Ashtadhyayi (Panini's grammar), several small tracts on ethics and morality, Vedic rituals and sacraments and on criticism of rival doctrines (such as Advaita Vedanta). The Paropakarini Sabha located in the Indian city of Ajmer was founded by the Swami himself to publish his works and Vedic texts.

- Satyartha Prakash/Light of Truth. Translated to English, published in 1908; New Delhi: Sarvadeshik Arya Pratinidhi Sabha, 1975.

- An Introduction to the Commentary on the Vedas. Ed. B. Ghasi Ram, Meerut, 1925; New Delhi : Meharchand lachhmandas Publications, 1981.

- Glorious Thoughts of Swami Dayananda. Ed. Sen, N.B. New Delhi: New Book Society of India.

- Autobiography. Ed. Kripal Chandra Yadav, New Delhi: Manohar, 1978.

- The philosophy of religion in India. Delhi: Bharatiya Kala Prakashan, 2005. ISBN 8180900797

Notes

- â New Zealand Arya Samaj, Ten Principles of the Arya Samaj. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- â Griffiths, p. 202-3.

- â Griffiths, p. 200.

- â Ruthven, 108.

- â Sri Aurobindo, The Secret of the Veda (Volume 10). Retrieved September 13, 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Griffiths, Paul J. Christianity Through Non-Christian Eyes. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1990. ISBN 0883446618

- Lata, Prem. Swami Dayananda Sarasvati. New Delhi: Sumit Publications, 1990. ISBN 978-8170001140

- Ruthven, Malise. Fundamentalism: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0199212705

- Salmond, N.A. Hindu Iconoclasts: Rammohun Roy, Dayananda Sarasvati and Nineteenth Century Polemics Against Idolatry. Waterloo, Ont: Published for the Canadian Corp. for Studies in Religion by Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0889204195

- Sarasvati, Dayananda. Autobiography of Swami Dayanand Saraswati. New Delhi: Manohar Book Service, 1976.

External links

All links retrieved January 28, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.