Battle of Chattanooga

| Battle of Chattanooga | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| United States of America | Confederate States of America | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Ulysses S. Grant | Braxton Bragg | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Military Division of the Mississippi (~56,000) | Army of Tennessee (~46,000) | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 5,824 (753 killed, 4,722 wounded, 349 missing) | 6,667 (361 killed, 2,160 wounded, 4,146 missing/captured) | ||||||

There were three Battles of Chattanooga fought in or near Chattanooga, Tennessee in the American Civil War. The First Battle of Chattanooga, Tennessee (June 7-8, 1862) was part of the Confederate Heartland Offensive Campaign, and involved what amounted to a minor artillery bombardment by Union forces under Brigadier General James Negley against Confederate Major General Edmund Kirby Smith. This action effected no change and ended at an impasse. The Union Army did not advance and the Confederates remained in Chattanooga.

The Second Battle of Chattanooga (August 21, 1863) was part of the Chickamauga Campaign. Another artillery bombardment, this time more intense than the previous year's, convinced Confederate general Braxton Bragg to evacuate the city, just prior to the Battle of Chickamauga (September 19–20) which resulted in a decisive Confederate victory despite staunch and valiant efforts on the part of Union General George Thomas. Gallantly, Braxton Bragg allowed the Union forces to withdraw unimpeded back to Chattanooga. The good outcome for the Union Army was that the loss forced the Federal government to pay more attention to the fighting in the west.

The Third Battle of Chattanooga (November 23-25, 1863) is the battle most popularly known as "The Battle of Chattanooga" and was referred to at the time as "Raising the Siege at Chattanooga." Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant relieved besieged Union defenders of Chattanooga and defeated Braxton Bragg's forces in three days with repeated assaults on Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, until the Confederate line broke.

Three times the the Northern states Union Army attempted to split the Southern states under a "divide and conquer" strategy. The third attempt proved the Union Army victorious, and began the final stages of the American Civil War. Following Grant's victory at Chattanooga, Union forces under General William Tecumseh Sherman marched into Georgia and through Atlanta beginning what today is termed "Sherman's March to Sea," thus effectively ending the war militarily for the South.

The first battle

| First Battle of Chattanooga | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| United States of America | Confederate States of America | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| James S. Negley | E. Kirby Smith | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| One division of the Dept of the Ohio | Army of Kentucky | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 23 | 65 | ||||||

The first part of the Battle of Chattanooga was a minor battle occurring from June 7 to June 8, 1862. In late spring 1862, the Confederacy split its forces in Tennessee into several small commands in an attempt to complicate Federal operations. The Union army had to redistribute its forces to counter the Confederate command structure changes. Major General Ormsby M. Mitchel received orders to take his division to Huntsville, Alabama, to repair railroads in the area. Soon, he occupied more than one hundred miles along the Nashville & Chattanooga and Memphis and Charleston railroads. In May, Mitchel and his men fought with Major General Edmund Kirby Smith’s men.

After Mitchel received command of all Federal troops between Nashville and Huntsville, on May 29, he ordered brigadier general James Negley with a small division to lead an expedition to capture Chattanooga. This force arrived before Chattanooga on June 7. Negley ordered the 79th Pennsylvania Volunteers out to reconnoiter. It found the Confederates entrenched on the opposite side of the river along the banks and atop Cameron Hill. Negley brought up two artillery batteries to open fire on the Confederate troops and the town and sent infantry to the river bank to act as sharpshooters. The Union bombardment of Chattanooga continued throughout the 7th and until noon on the 8th. The Confederates retaliated, but it was uncoordinated and sloppy. On June 10, Smith, who had arrived on the 8th, reported that Negley had withdrawn and the Confederate loss was minor. This attack on Chattanooga was a warning that Union troops could mount assaults at will.

The second battle

The second part of the Battle of Chattanooga began 50 miles northwest of Chattanooga where Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee had 47,000 men stretched across a line preventing a direct Union advance. Major General William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland, believed he did have enough men and brilliantly moved as if he were going to attack Bragg's left flank. Then he quickly reversed himself and went in the opposite direction. Before the Bragg realized what Rosecrans was up to, Rosecrans was at his rear on his right flank. Rosecrans bluffed and attack and then slipped off in the opposite direction. Completely bewildered, Bragg had to retreat and moved his army all the way to Chattanooga. For more than a month, Rosecrans tried to find a way to get at Bragg's forces. Unexpectedly Rosecrans found a crossing of the winding Tennessee River and found nothing was between his army and Bragg's except Lookout Mountain, southeast of Chattanooga. On August 16, 1863, Rosecrans, launched a campaign to take Chattanooga. Again, Rosecrans decided against a direct move. He went southeast looking for a pass through a series of gaps in Lookout Mountain.

The second battle of Chattanooga began on August 21, 1863, as the opening battle in the Chickamauga Campaign. Colonel John T. Wilder’s brigade of the Union 4th Division, XIV Army Corps, marched to a location northeast of Chattanooga where the Confederates could see them, reinforcing General Braxton Bragg’s expectations of a Union attack on the town from that direction. On August 21, Wilder reached the Tennessee River opposite Chattanooga and ordered the 18th Indiana Light Artillery to begin shelling the town. The shells caught many soldiers and civilians in town in church observing a day of prayer and fasting. The bombardment sank two steamers docked at the landing and created a great deal of consternation amongst the Confederates. This continued periodically over the next two weeks, the shelling helped keep Bragg's attention to the northeast while the bulk of Rosecrans' army crossed the Tennessee River well west and south of Chattanooga. When Bragg learned on September 8, that the Union army was in force southwest of the city, he abandoned Chattanooga and moved his army into Georgia and met up with two divisions of General James Longstreet's Army of Northern Virginia. Rosecrans moved his army through the mountain passes in search of Bragg, whom he believed was in full retreat. Reinforced with Longstreet's divisions, Bragg began moving against Rosecrans to counterattack. Too late Rosecrans realized he was in trouble. On September 18, at Chickamauga Creek 12 miles southeast of Chattanooga, Bragg's men fell upon Rosecran's and a three day battle erupted. Chickamauga is a name the local Native Americans gave to the creek which translates as "River of Death." Historians called it one of the bloodiest battles of the war. The Confederates succeeded in routing the Union forces, with the exception of General George Thomas, whose men quickly filled a hole in the Union line and prevented Longstreet's forces from causing the battle to become a complete Union disaster. His quick action earned Thomas the sorbiquet, "The Rock of Chickamauga." A reported 17,800 confederate soldiers became casualties that day, while union losses were 16,600 men. Rather than press his advantage, at the end of the third day, on September 20, Bragg allowed the Union Army to retreat to Chattanooga.

The third battle

The third part of the Battle of Chattanooga (popularly known as The Battle of Chattanooga) was fought from November 23 to November 25, 1863, in the American Civil War. By defeating the Confederate forces of General Braxton Bragg, Union Army Major General Ulysses S. Grant eliminated the last Confederate control of Tennessee and opened the door to an invasion of the deep Southern United States that would lead to the Atlanta Campaign of 1864.

Prelude to battle

After their disastrous defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga, the 40,000 men of the Union Army of the Cumberland under Major General William Rosecrans retreated to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Confederate General Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee besieged the city, threatening to starve the Union forces into surrender. His pursuit to the city outskirts had been leisurely, giving the Union soldiers time to prepare defenses. Bragg's troops established themselves on Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain, both of which had excellent views of the city, the river, and the Union's supply lines. Confederate troops launched raids on all supply wagons heading toward Chattanooga, which made it necessary for the Union to find another way to feed their men.

The Union government, alarmed by the potential for defeat, sent reinforcements. On October 17, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant received command of the Western armies, designated the Military Division of the Mississippi; he moved to reinforce Chattanooga and replaced Rosecrans with Major General George H. Thomas. Devising a plan known as the "Cracker Line," Grant's chief engineer, William F. "Baldy" Smith, launched a surprise amphibious landing at Brown's Ferry that opened the Tennessee River by linking up Thomas's Army of the Cumberland with a relief column of 20,000 troops led by Major General Joseph Hooker, thus allowing supplies and reinforcements to flow into Chattanooga, greatly increasing the chances for Grant's forces. In response, Bragg ordered Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet to force the Federals out of Lookout Valley. The ensuing Battle of Wauhatchie (October 28 to October 29, 1863) was one of the war's few battles fought exclusively at night. The Confederates were repulsed and the Cracker Line was secured.

Bragg weakened his forces by sending Longstreet's corps against Major General Ambrose Burnside, near Knoxville. When Major General William T. Sherman arrived with his four divisions (20,000 men) in mid-November, Grant began offensive operations.

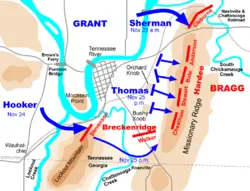

November 23: Initial movements

On November 23, Union forces under Thomas struck out and advanced east to capture a line from Orchard Knob to Bushy Knob, placing them halfway to the summit of Missionary Ridge. The advance was made in broad daylight and met little Confederate resistance. Bragg moved Walker's division from Lookout Mountain to strengthen his right flank.

November 24: Battle of Lookout Mountain

The plan for November 24 was a two-pronged attack—Hooker against the Confederate left, Sherman against the right. Hooker's three divisions struck at dawn at Lookout Mountain and found that the defile between the mountain and the river had not been secured. They barreled right through this opening; the assault ended around 3:00 p.m. when ammunition ran low and fog had enveloped the mountain. This action has been called the "Battle Above the Clouds" due to that fog. Bragg withdrew his forces from the southern end of the mountain to a line behind Chattanooga Creek, burning the bridges behind him.

Sherman crossed the Tennessee River successfully, but his assault was then delayed and the division of Patrick Cleburne was rushed in to reinforce the Confederate right flank. However, no attack occurred.

November 25: Battle of Missionary Ridge

On November 25, Grant changed his plan and called for a double envelopment by Sherman and Hooker. Thomas was to advance after Sherman reached Battle of Missionary Ridge from the north. The Ridge was a formidable defensive position, manned in depth, and Grant knew that a frontal assault against it would be suicidal, unless it could be arranged in support of the flanking attacks by Sherman and Hooker. As the morning progressed, Sherman was unable to break Cleburne's line and Hooker's advance was slowed by the burned bridges on the creek. At 3:30 p.m., Grant was concerned that Bragg was reinforcing his right flank at Sherman's expense. Hence, he ordered Thomas to move forward and try to seize the first of three lines of Confederate entrenchments to his front. The Union soldiers moved forward and captured the first line, but were subjected there to punishing fire from the two remaining Confederate lines up the ridge. Most of these units had been at the disastrous loss at Chickamauga and had suffered the taunts by Sherman's and Burnside's newly arrived forces. Now they were under fire from above with no apparent plan to advance or move back. Without orders, the Union soldiers continued the attack against the remaining lines. They advanced doggedly up the steep slope, shouting "Chickamauga, Chickamauga!" until they finally overwhelmed and captured the remaining Confederate lines. Bragg had misplaced his artillery on the crest of the ridge, rather than the military crest, and it was unable to provide effective fire. Nonetheless, the Army of the Cumberland's ascent of Missionary Ridge was one of the war's most dramatic events. A Union officer recalled that, "little regard to formation was observed. Each battalion assumed a triangular shape, the colors at the apex. … [a] color-bearer dashes ahead of the line and falls. A comrade grasps the flag. … He, too, falls. Then another picks it up … waves it defiantly, and as if bearing a charmed life, he advances steadily towards the top…."

Grant was initially furious that his orders had not been followed exactly. Thomas was taken by surprise as well, knowing that his head would be on the chopping block if the assault failed. But it succeeded. By 4:30 p.m., the center of Bragg's line broke and fled in panic requiring the abandonment of Missionary Ridge and a headlong retreat into Georgia.

Aftermath

During the night, Bragg ordered his army to withdraw toward Dalton; Grant was unable to organize an effective pursuit. Casualties for the Union Army amounted to 5,824 (753 killed, 4,722 wounded, and 349 missing) of about 56,000 engaged; Confederate casualties were 6,667 (361 killed, 2,160 wounded, and 4,146 missing, mostly prisoners) of 46,000. When a chaplain asked General Thomas whether the dead should be sorted and buried by state, Thomas replied "Mix 'em up. I'm tired of States' rights."

One of the Confederacy's two major armies was routed. The Union held Chattanooga, the "Gateway to the Lower South." It became the supply and logistics base for Sherman's 1864 Atlanta Campaign, and Grant had won his final battle in the west prior to receiving command of all Union armies in March 1864.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Catton, Bruce. The American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War. New York Bonanza Books, 1982, 1960. ISBN 0517385562

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0684849445

- McDonough, James Lee. Chattanooga: A Death Grip on the Confederacy. Knoxville, Tennessee The University of Tennessee Press, 1984. ISBN 0870494252

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Third_Battle_of_Chattanooga history

- Second_Battle_of_Chattanooga history

- First_Battle_of_Chattanooga history

- Battle_of_Chattanooga history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.