Bahadur Shah II

| 'Abu Zafar Sirajuddin Muhammad Bahadur Shah Zafar اب٠ظÙر سÙراج٠اÙÙدÛÙ Ù Ø٠د بÙÛادر Ø´Ø§Û Ø¸Ùر' | ||

|---|---|---|

| Emperor of the Mughal Empire | ||

| Reign | September 28, 1838 â September 14, 1857 | |

| Titles | بÙÛادر Ø´Ø§Û Ø¯ÙÙ ; Mughal Emperor | |

| Born | October 24, 1775 | |

| Delhi, Mughal Empire | ||

| Died | November 7, 1862 | |

| Rangoon, Burma, British Raj | ||

| Buried | Rangoon, Burma | |

| Predecessor | Akbar Shah II | |

| Successor | Mughal Empire abolished Descendants: 22 sons and at least 32 daughters | |

| Father | Akbar Shah II | |

| Mother | Lalbai | |

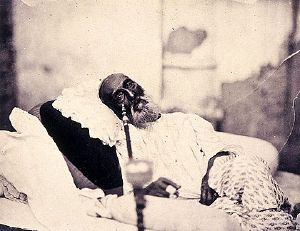

Abu Zafar Sirajuddin Muhammad Bahadur Shah Zafar also known as Bahadur Shah or Bahadur Shah II (October 24, 1775 â November 7, 1862) was the last of the Moghul emperors in India, as well as the last ruler of the Timurid Dynasty. He was the son of Akbar Shah II by his Hindu wife Lalbai. He became the Mughal Emperor upon his father's death on September 28, 1838, already a purely symbolic and titular role while the British East India Company exercised real power. Technically, the British were the Emperorâs agents. What residual political authority he had was confined to the City of Delhi, where he lived on a British pension in the Red Fort. Somewhat derisively, the British referred to him as the "King of Delhi." As a result of reluctantly giving his name to the revolt of 1857, he was tried for treason by the British and exiled to Burma, where he died. How a sovereign could rebel against himself remains a puzzle.

Zafar was his nom de plume (takhallus) as an Urdu poet. He is recognized as one of the greatest poets in this language of his day, some say he is the greatest ever. His poetry lamented loss and Indiaâs debasement.

At the end, Shah Bahadur cut a sad and tragic figure, whose eulogy mourned that he could not even be buried in âtwo yardsâ of his beloved homeland. Yet to describe him as weak or as presiding over the end of his empire is unfair. No Mughal had exercised real power since Alamgir II, himself a puppet of the Afghan king, Ahmad Shah Durrani. Within the limited domain of Delhiâs social life, however, Bahadur Shah II did preside over a period of flourishing cultural life. Relations between different religious communities, which would become increasingly strained under Britainâs âdivide and ruleâ policy, were very cordial, with a great deal of interaction and sharing of festivals. Later, he was transformed into a symbol of Indian anti-British resistance. This reads too much back into history. Yet he does deserve credit for leading where he could, culturally, poetically and as a champion of inter-religious harmony in a land that has prided itself on its inclusiveness and tolerance.

As Emperor

Bahadur was the son of Akbar Shah II and his Hindu wife Lalbai. Over 60 when he became Emperor, he inherited little territory apart from the city of Delhi, itself occupied by the British since 1893. In fact, any authority he did have barely extended outside the Red Fort. The last Moghul to exercise any real authority had been Alamgir II, and he had ruled as a puppet of the Afghan King, Ahmad Shah Durrani and as a tool in the hands of his own vizier, who made him emperor and later killed him. The Moghuls were already impoverished (ever since the 1739 Persian sack of Delhi under Nader Shah) when the Peacock Throne, Koh-i-Noor diamond and the contents of the state treasury, were carried off.

Alamgirâs own son, Shah Alam II became the first Moghul to live as a pensioner of the British (1803-1805). His son, Shah Bahadur IIâs father, Akbar enjoyed the title of emperor but possessed neither money nor power. Legally agents of the Mughal emperor under the Treaty of Allahabad (1765) when Shah Alam II surrendered them the right to collect taxes in Bengal, Orissa, and Bihar, the British maintained the fiction that the emperor was sovereign while extending their own power and authority at the expense of his. The emperor was allowed a pension and authority to collect some taxes, and maintain a token force in Delhi, but he posed no threat to any power in India.

Cultural Leader

In his 2007 biography of Shah Bahadur II, William Dalrymple describes Delhi, where his court was home to poets and literati, as a thriving multi-cultural, multi-religious society roughly half Muslim and half-Hindu. The son of a Hindu mother, Shah Bahadur took part in Hindu festivals, as did other Muslims. Bahadur Shah II himself did not interest himself in statecraft or possess any imperial ambitions. Indeed, it is difficult to see how he could have entertained any such ambitions. Arguably, what he did do was lead where he could, in championing the type of multi-cultural society over which, at their best, his predecessorsânot withstanding periods when Hindus and Sikhs were persecutedâhad ruled. Poets such as Ghalib, Dagh, Mumin, and Zauq (Dhawq) gathered at his court. The British accused him of extravagance and of living a profligate life. There appears to be little evidence to support this.

Using his penname, Zafar, he was himself a noted Urdu poetâsome say the greatestâwriting a large number of Urdu ghazals. He was also a musician and calligrapher. While some part of his opus was lost or destroyed during the unrest of 1857-1858, a large collection did survive, and was later compiled into the Kulliyyat-i Zafar. A sense of loss haunts his poetry. He is attributedâalthough this attribution has been questionedâwith the following self-eulogy. India has issued a postage stamp bearing the Urdu text in honor of Bahadur Shah II. Even if he did not pen this poem, it expresses what must have been his own sentiments:

- My heart is not happy in this despoiled land

- Who has ever felt fulfilled in this transient world

- Tell these emotions to go dwell elsewhere

- Where is there space for them in this besmirched (bloodied) heart?

- The nightingale laments neither to the gardener nor to the hunter

- Imprisonment was written in fate in the season of spring

- I had requested for a long life a life of four days

- Two passed by in pining, and two in waiting.

- How unlucky is Zafar! For burial

- Even two yards of land were not to be had, in the land (of the) beloved."

- Another of the verses reads:

- Zafar, no matter how smart and witty one may be, he is not a man

- Who in good times forgot God, and who in anger did not fear Him.[1]

Events of 1857

As the Indian rebellion of 1857 spread, the Indian regiments seized Delhi and acclaimed Zafar their nominal leader, despite his own reservations. Zafar was viewed as a figure who could unite all Indians, Hindu and Muslim alike, and someone who would be acceptable to the Indian princes as sovereign. Zafar was the least threatening and least ambitious of monarchs and the restoration of the Mughal Empire would presumably be more acceptable as a uniting force to these rulers than the domination of any other Indian kingdom. Now an octogenarian, Zafar didâalthough he had deep reservationsâallow his name to be used as titular leader of the revolt. War of independence is a more appropriate description, although because the war began with soldiers in the employment of the British, rebelling against their officers, it was called a âmutiny.â Whatever description is preferred, it was a war in which the people of India rebelled against rule by a foreign, colonial power and in allowing his name to be used Shah Bahadur II did so as the legal sovereign of, in theory, a large part of India. Sadly, he then saw what had been a thriving city of culture, and a city at peace, transformed into a bloodbath of death and destruction.

When the victory of the British became certain, Zafar took refuge at Humayun's Tomb, in an area that was then at the outskirts of Delhi, and hid there. British forces led by Major Hodson surrounded the tomb and compelled his surrender. Numerous male members of his family were killed by the British, who imprisoned or exiled the surviving members of the Mughal dynasty. Zafar himself, found guilty of treason, was exiled to Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar) in 1858 along with his wife Zeenat Mahal and some of the remaining members of the family. His trial could not have been legal. Nonetheless, it marked the end of more than three centuries of Mughal rule in India. The British declared Victoria of the United Kingdom as sovereign (later Empress} of India, which itself indicates that she did not claim sovereignty before 1858.

Bahadur Shah died in exile on November 7, 1862. He was buried near the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, at the site that later became known as Bahadur Shah Zafar Dargah.[2] His wife Zinat Mahal died in 1886.

Legacy

Modern India views him as one of its first nationalists, someone who actively opposed British rule in India. In 1959, the All India Bahadur Shah Zafar Academy was founded expressly to spread awareness about his contribution to the first national freedom movement of India. Several movies in Hindi/Urdu have depicted his role during the rebellion of 1857, including Bahadur Shah Zafar (1986) directed by B.R. Chopra. In 2002 Arjeet gupta directed a short TV film about his living descendants, The Living Moghuls: from Royalty to Anonymity. There are roads bearing his name in New Delhi, Lahore, Varanasi and other cities. A statue of Bahadur Shah Zafar has been erected at Vijayanagaram palace in Varanasi. In Bangladesh, the Victoria Park of old Dhaka has been renamed as Bahadur Shah Zafar Park. His poetry remains a cultural legacy of value. He was as much a victim of circumstances as a maker of history, yet he can be credited with sustaining pride in Indiaâs past and with nourishing, in Delhi where he did have some authority, a multi-religious society that reflects the best periods of the Mughal heritage, rather than its more intolerant episodes.

Family

Bahadur Shah Zafar is known to have had four wives and numerous concubines. In order of marriage, his wives were:[3]

- Begum Ashraf Mahal

- Begum Akhtar Mahal

- Begum Zeenat Mahal

- Begum Taj Mahal

Zafar had 22 sons, including:

- Mirza Fath-ul-Mulk Bahadur (alias Mirza Fakhru)

- Mirza Mughal

- Mirza Khazr Sultan

- Jawan Bakht

- Mirza Quaish

- Mirza Shah Abbas

He also had at least 32 daughters, including:

- Rabeya Begum

- Begum Fatima Sultan

- Kulsum Zamani Begum

- Raunaq Zamani Begum (possibly a granddaughter)

Most of his sons and grandsons were killed during or in the aftermath of the rebellion of 1857. Of those who survived, the following three lines of descent are known:

- Delhi line - son: Mirza Fath-ul-Mulk Bahadur (alias Mirza Fakhru); grandson: Mirza Farkhunda Jamal; great-grandchildren: Hamid Shah and Begum Qamar Sultan.

- Howrah line - son: Jawan Bakht, grandson: Jamshid Bakht, great-grandson: Mirza Muhammad Bedar Bakht (married Sultana Begum, who currently runs a tea stall in Howrah).

- Hyderabad line - son: Mirza Quaish, grandson: Mirza Abdullah, great-grandson: Mirza Pyare (married Habib Begum), great-great-granddaughter: Begum Laila Ummahani (married Yakub Habeebuddin Tucy) and lived with her children in anonymity for years (her surviving sons Ziauddin Tucy is a retired government employee and Masiuddin Tucy is a food consultant).[4]

Descendants of Mughal rulers other than Bahadur Shah Zafar also survive to this day. They include the line of Jalaluddin Mirza in Bengal, who served at the court of the Maharaja of Dighapatia, and the Toluqari family, which also claims to be descended from Baron Gardner.

See also

| Preceded by: Akbar Shah II |

Mughal Emperor 1837â1858 |

Succeeded by: Mughal Empire abolished |

Notes

- â Bahadur Shah II IndiaZone.net Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- â Bahadur Shah Zafar Kapadia.com.

- â Abdoolah Farooqi, 1989, Extracts from a book on Bahadur Shah Zafar Farooqi Book Depot.

- â Ayanjit Sen, Film traces lives of India's Moghuls BBC, August 10, 2002. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ahmed, Syed Z. Twilight of an Empire. Lahore, PK: Ferozsons, 1996. ISBN 978-9690102140

- Bérinstain, Valérie. India and the Mughal Dynasty. New York, NY: Abrams, 1998. ISBN 978-0810928565

- Burke, S. M., and Salim al-Din Quraishi. Bahadur Shah: The Last Moghul Emperor of India. Lahore, PK: Sang-e-Meel, 1995. ISBN 978-9693506266

- Dalrymple, William. The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty: Delhi, 1857. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007. ISBN 978-1400043101

- Eraly, Abraham. The Moghul Throne: the Saga of Indiaâs Great Emperors. London, UK: Phoenix, 2004. ISBN 978-0753817582

- Garrett, H. L. O. The Trial of Muhammad Bahadur Shah, ex-King of Delhi. Lahore, PK: Research and Publication Centre, National College of Arts, 2003.

- Husain, Syed Mahdi. Bahadur Shah Zafar and the War of 1857 in Delhi. Delhi, IN: Aakar Books, 2006. ISBN 978-8187879916

- Nayar, Pramod K. The Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar. Hyderabad, IN: Orient Longman, 2007. ISBN 978-8125032700

- Richards, John F. The Mughal Empire. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0521566032

External links

All links retrieved August 26, 2023.

- BBC Report on Bahadur Shah's possible descendants in Hyderabad

- An article on Bahadur Shah's descendants in Kolkata

- Forgotten Empress: Sultana Beghum sells tea in Kolkata

- Poetry on urdupoetry.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.