Alliterative verse

In prosody, alliterative verse is a form of verse that uses alliteration as the principal structuring device to unify lines of poetry, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme.

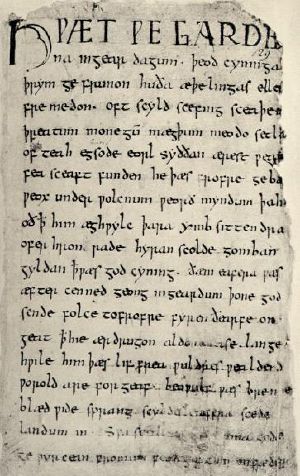

The most intensively studied traditions of alliterative verse are those found in the oldest literature of many Germanic languages. Alliterative verse, in various forms, is found widely in the literary traditions of the early Germanic languages. The Old English epic Beowulf, as well as most other Old English poetry, the Old High German Muspilli, the Old Saxon Heliand, and the Old Norse Poetic Edda all use alliterative verse.

Alliterative verse can be found in many other languages as well, although rarely with the systematic rigor of Germanic forms. The Finnish Kalevala and the Estonian Kalevipoeg both use alliterative forms derived from folk tradition. Traditional Turkic verse, for example that of the Uyghur, is also alliterative.

Common Germanic origins and features

The poetic forms found in the various Germanic languages are not identical, but there is sufficient similarity to make it clear that they are closely related traditions, stemming from a common Germanic source. Our knowledge about that common tradition, however, is based almost entirely on inference from surviving poetry.

Snorri Sturluson, author of the Prose Edda, an example of alliterative verse, describes metrical patterns and poetic devices used by skaldic poets around the year 1200 C.E.. Snorri's description has served as the starting point for scholars to reconstruct alliterative meters beyond those of Old Norse. There have been many different metrical theories proposed, all of them attended with controversy. Looked at broadly, however, certain basic features are common from the earliest to the latest poetry.

Alliterative verse has been found in some of the earliest monuments of Germanic literature. The Golden horns of Gallehus, discovered in Denmark and likely dating to the fourth century, bears this Runic inscription in Proto-Norse:

x / x x x / x x / x / x x ek hlewagastir holtijar || horna tawidô

(I, Hlewagastir (son?) of Holt, made the horn.)

This inscription contains four strongly stressed syllables, the first three of which alliterate on <h> /x/, essentially the same pattern found in much latter verse.

Originally all alliterative poetry was composed and transmitted orally, and much has been lost through time since it went unrecorded. The degree to which writing may have altered this oral art form remains in much dispute. Nevertheless, there is a broad consensus among scholars that the written verse retains many (and some would argue almost all) of the features of the spoken language because alliteration serves as a mnemonic device.

Alliteration fits naturally with the prosodic patterns of Germanic languages. Alliteration essentially involves matching the left edges of stressed syllables. Early Germanic languages share a left-prominent prosodic pattern. In other words, stress falls on the root syllable of a word. This is normally the initial syllable, except where the root is preceded by an unstressed prefix (as in past participles, for example).

The core metrical features of traditional Germanic alliterative verse are as follows:

- A long-line is divided into two half-lines. Half-lines are also known as verses or hemistichs; the first is called the a-verse (or on-verse), the second the b-verse (or off-verse).

- A heavy pause, or cæsura, separates the verses.

- Each verse usually has two strongly stressed syllables, or "lifts."

- The first lift in the b-verse must alliterate with either or both lifts in the a-verse.

- The second lift in the b-verse does not alliterate with the first lifts.

The patterns of unstressed syllables vary significantly in the alliterative traditions of different Germanic languages. The rules for these patterns remain controversial and imperfectly understood.

The need to find an appropriate alliterating word gave certain other distinctive features to alliterative verse as well. Alliterative poets drew on a specialized vocabulary of poetic synonyms rarely used in prose texts and used standard images and metaphors called kennings.

Old English poetic forms

Old English poetry appears to be based upon one system of verse construction, a system which remained remarkably consistent for centuries, although some patterns of classical Old English verse begin to break down at the end of the Old English period.

The most widely used system of classification is based on that developed by Eduard Sievers. It should be emphasized that Sievers' system is fundamentally a method of categorization rather than a full theory of meter. It does not, in other words, purport to describe the system the scops actually used to compose their verse, nor does it explain why certain patterns are favored or avoided. Sievers divided verses into five basic types, labeled A-E. The system is founded upon accent, alliteration, the quantity of vowels, and patterns of syllabic accentuation.

Accent

A line of poetry in Old English consists of two half-lines or verses, distichs, with a pause or caesura in the middle of the line. Each half-line has two accented syllables, as the following example from the poem Battle of Maldon, spoken by the warrior Beorhtwold, demonstrates:

Hige sceal þe heardra, || heorte þe cenre, mod sceal þe mare, || þe ure mægen lytlað

- ("Will must be the harder, courage the bolder, spirit must be the more, as our might lessens.")

Alliteration

Alliteration is the principal binding agent of Old English poetry. Two syllables alliterate when they begin with the same sound; all vowels alliterate together, but the consonant clusters st-, sp- and sc- are treated as separate sounds (so st- does not alliterate with s- or sp-). On the other hand, in Old English unpalatized c (pronounced <k>, /k/) alliterated with palatized c (pronounced <ch>, /tʃ/), and unpalatized g (pronounced <g>, /g/) likewise alliterated with palatized g (pronounced <y>, /j/). (This is because the poetic form was inherited from a time before /k/ and /g/ had split into palatized and unpalatized variants.) (English transliteration is in <angle brackets>, the IPA in /slashes/.)

The first stressed syllable of the off-verse, or second half-line, usually alliterates with one or both of the stressed syllables of the on-verse, or first half-line. The second stressed syllable of the off-verse does not usually alliterate with the others.

Middle English

Just as rhyme was seen in some Anglo-Saxon poems (e.g. The Rhyming Poem, and, to some degree, The Proverbs of Alfred), the use of alliterative verse continued into Middle English. Layamon's Brut, written in about 1215, uses a loose alliterative scheme. The Pearl Poet uses one of the most sophisticated alliterative schemes extant in Pearl, Cleanness, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Even later, William Langland's Piers Plowman is a major work in English that is written in alliterative verse; it was written between 1360 and 1399. Though a thousand years have passed between this work and the Golden Horn of Gallehus, the poetic form remains much the same:

A feir feld full of folk || fond I þer bitwene,

Of alle maner of men, || þe mene and þe riche,

Worchinge and wandringe || as þe world askeþ.

Among them I found a fair field full of people

All manner of men, the poor and the rich Working and wandering as the world requires.

Alliteration was sometimes used together with rhyme in Middle English work, as in Pearl. In general, Middle English poets were somewhat loose about the number of stresses; in Sir Gawain, for instance, there are many lines with additional alliterating stresses (e.g. l.2, "the borgh brittened and brent to brondez and askez"), and the medial pause is not always strictly maintained.

After the fifteenth century, alliterative verse became fairly uncommon, although some alliterative poems, such as Pierce the Ploughman's Crede (ca. 1400) and William Dunbar's superb Tretis of the Tua Marriit Wemen and the Wedo (ca. 1500) were written in the form in the fifteenth century. However, by 1600, the four-beat alliterative line had completely vanished, at least from the written tradition.

Modern revival

The twentieth century witnessed the beginnings of a revival in the use of alliterative verse. One modern author who studied alliterative verse and used it extensively in his fictional writings and poetry, was J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973). He wrote alliterative verse in modern English, in the style of Old English alliterative verse (he was one of the major Beowulf scholars of his time—see Beowulf: the monsters and the critics). Examples of Tolkien's alliterative verses include those written by him for the Rohirrim, a culture in The Lord of the Rings that borrowed many aspects from Anglo-Saxon culture. There are also many examples of alliterative verse in Tolkien's posthumously-published works in The History of Middle-earth series. Of these, the unfinished 'The Lay of the Children of Húrin', published in The Lays of Beleriand, is the longest. Another example of Tolkien's alliterative verse refers to Mirkwood (see the introduction to that article). Outside of his Middle-earth works, Tolkien also worked on alliterative modern English translations of several Middle English poems by the Pearl Poet: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo. These were published posthumously in 1975. In his lifetime, as well as the alliterative verse in The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien published The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son in 1953, an alliterative verse dialogue recounting a historical fictional account of The Battle of Maldon.

Other twentieth century poets who used alliterative verse include W. H. Auden (1907-1973) who wrote a number of poems. For example, his The Age of Anxiety, is written in alliterative verse, modified only slightly to fit the phonetic patterns of modern English. The noun-laden style of the headlines makes the style of alliterative verse particularly apt for Auden's poem:

Now the news. Night raids on Five cities. Fires started. Pressure applied by pincer movement In threatening thrust. Third Division Enlarges beachhead. Lucky charm Saves sniper. Sabotage hinted In steel-mill stoppage. . . .

Other poets who have experimented with modern alliterative English verse include Ezra Pound, see his "The Seafarer," and Richard Wilbur, whose Junk opens with the lines:

An axe angles

- from my neighbor's ashcan;

It is hell's handiwork,

- the wood not hickory.

The flow of the grain

- not faithfully followed.

The shivered shaft

- rises from a shellheap

Of plastic playthings,

- paper plates.

Many translations of Beowulf use alliterative techniques. Among recent ones that of Seamus Heaney loosely follows the rules of modern alliterative verse while the translation of Alan Sullivan and Timothy Murphy follows those rules more closely.

Building on the work of Christian authors, in particular members of The Inklings literary discussion group associated with Tolkien and C.S. Lewis at the University of Oxford in the 1930s and 1940s, alliterative verse can be said to have experienced a significant revival in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Dennis Wise (2023) points out that one of the main ways alliterative verse has revived its popularity is in the science fiction community where worlds, both old and new, are imagined and brought to life. Today, a substantial number of poets and writers include it as a tool to create new ways to seeing the world.

Old Norse poetic forms

The inherited form of alliterative verse was modified somewhat in Old Norse poetry. In Old Norse, as a result of phonetic changes from the original common Germanic language, many unstressed syllables were lost. This lent Old Norse verse a characteristic terseness; the lifts tended to be crowded together at the expense of the weak syllables. In some lines, the weak syllables have been entirely suppressed. From the Hávamál:

- Deyr fé || deyja frændr

- ("Cattle die; friends die. . .")

The various names of the Old Norse verse forms are given in the Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson. The Háttatal, or "list of verse forms," contains the names and characteristics of each of the fixed forms of Norse poetry.

Fornyrðislag

A verse form close to that of Beowulf existed in runestones and in the Old Norse Eddas; in Norse, it was called fornyrðislag, which means "past-words-made" or "way of ancient words." The Norse poets tended to break up their verses into stanzas from two to eight lines (or more), rather than writing continuous verse after the Old English model. The loss of unstressed syllables made these verses seem denser and more emphatic. The Norse poets, unlike the Old English poets, tended to make each line a complete syntactic unit, avoiding enjambment where a thought begun on one line continues through the following lines; only seldom do they begin a new sentence in the second half-line. This example is from the Waking of Angantyr:

- Vaki, Angantýr! || vekr þik Hervǫr,

- eingadóttir || ykkr Tófu!

- Selðu ór haugi || hvassan mæki

- þann's Svafrlama || slógu dvergar.

- (Awaken, Angantyr! It is Hervor who awakens you, your only daughter by Tófa! Yield up from your grave the mighty sword that the dwarves forged for Svafrlami.")

Fornyrðislag has two lifts-per-half-line, with two or three (sometimes one) unstressed syllables. At least two lifts, usually three, alliterate, always including the main stave (the first lift of the second half-line).

Fornyrðislag had a variant form called málaháttr ("speech meter"), which adds an unstressed syllable to each half-line, making six to eight (sometimes up to ten) unstressed syllables per line.

Ljóðaháttr

Change in form came with the development of ljóðaháttr, which means "song" or "ballad meter," a stanzaic verse form that created four line stanzas. The odd numbered lines were almost standard lines of alliterative verse with four lifts and two or three alliterations, with cæsura; the even numbered lines had three lifts and two alliterations, and no cæsura. The following example is from Freyr's lament in Skírnismál:

- Lǫng es nótt, || lǫng es ǫnnur,

- hvé mega ek þreyja þrjár?

- Opt mér mánaðr || minni þótti

- en sjá halfa hýnótt.

- (Long is one night, long is the next; how can I bear three? A month has often seemed less to me than this half "hýnótt" (word of unclear meaning)).

A number of variants occurred in ljóðaháttr, including galdraháttr or kviðuháttr ("incantation meter"), which adds a fifth short (three-lift) line to the end of the stanza; in this form, usually the fifth line echoes the fourth one.

Dróttkvætt

These verse forms were elaborated even more into the skaldic poetic form called the dróttkvætt, meaning "lordly verse," which added internal rhymes and other forms of assonance that go well beyond the requirements of Germanic alliterative verse. The dróttkvætt stanza had eight lines, each having three lifts. In addition to two or three alliterations, the odd numbered lines had partial rhyme of consonants (which was called skothending) with dissimilar vowels, not necessarily at the beginning of the word; the even lines contained internal rhyme (aðalhending) in the syllables, not necessarily at the end of the word. The form was subject to further restrictions: each half-line must have exactly six syllables, and each line must always end in a trochee.

The requirements of this verse form were so demanding that occasionally the text of the poems had to run parallel, with one thread of syntax running through the on-side of the half-lines, and another running through the off-side. According to the Fagrskinna collection of sagas, King Harald III of Norway uttered these lines of dróttkvætt at the Battle of Stamford Bridge; the internal assonances and the alliteration are bolded:

- Krjúpum vér fyr vápna,

- (valteigs), brǫkun eigi,

- (svá bauð Hildr), at hjaldri,

- (haldorð), í bug skjaldar.

- (Hátt bað mik), þar's mœttusk,

- (menskorð bera forðum),

- hlakkar íss ok hausar,

- (hjalmstall í gný malma).

- (In battle, we do not creep behind a shield before the din of weapons [so said the goddess of hawk-land {a valkyrja} true of words.] She who wore the necklace bade me to bear my head high in battle, when the battle-ice [a gleaming sword] seeks to shatter skulls.)

The bracketed words in the poem ("so said the goddess of hawk-land, true of words") are syntactically separate, but interspersed within the text of the rest of the verse. The elaborate kennings manifested here are also practically necessary in this complex and demanding form, as much to solve metrical difficulties as for the sake of vivid imagery. Intriguingly, the saga claims that Harald improvised these lines after he gave a lesser performance (in fornyrðislag); Harald judged that verse bad, and then offered this one in the more demanding form. While the exchange may be fictionalized, the scene illustrates the regard in which the form was held.

Most dróttkvætt poems that survive appear in one or another of the Norse Sagas; several of the sagas are biographies of skaldic poets.

Hrynhenda

Hrynhenda is a later development of dróttkvætt with eight syllables per line instead of six, but with the same rules for rhyme and alliteration. It is first attested around 985 in the so-called Hafgerðingadrápa of which four lines survive (alliterants and rhymes bolded):

- Mínar biðk at munka reyni

- meinalausan farar beina;

- heiðis haldi hárar foldar

- hallar dróttinn of mér stalli.

- I ask the tester of monks (God) for a safe journey; the lord of the palace of the high ground (God—here we have a kenning in four parts) keep the seat of the falcon (hand) over me.

The author was said to be a Christian from the Hebrides, who composed the poem asking God to keep him safe at sea. (Note: The third line is, in fact, over-alliterated. There should be exactly two alliterants in the odd-numbered lines.) The meter gained some popularity in courtly poetry, as the rhythm may sound more majestic than dróttkvætt.

Alliterative poetry is still practiced in Iceland in an unbroken tradition since the settlement.

German forms

The Old High German and Old Saxon corpus of alliterative verse is small. Less than 200 Old High German lines survive, in four works: the Hildebrandslied, Muspilli, the Merseburg Charms and the Wessobrunn Prayer. All four are preserved in forms that are clearly to some extent corrupt, suggesting that the scribes may themselves not have been entirely familiar with the poetic tradition. The two Old Saxon alliterative poems, the fragmentary Heliand and the even more fragmentary Genesis are both Christian poems, created as written works of [[The Bible}Biblical]] content based on Latin sources, and not derived from oral tradition.

However, both German traditions show one common feature which are much less common elsewhere: a proliferation of unaccented syllables. Generally these are parts of speech which would naturally be unstressed—pronouns, prepositions, articles, modal auxiliaries—but in the Old Saxon works there are also adjectives and lexical verbs. The unaccented syllables typically occur before the first stress in the half-line, and most often in the b-verse.

The Hildbrandslied, lines 4–5:

- Garutun se iro guðhamun, gurtun sih iro suert ana,

helidos, ubar hringa, do sie to dero hiltiu ritun.

- They prepared their fighting outfits, girded their swords on,

the heroes, over ringmail when they to that fight rode.

- They prepared their fighting outfits, girded their swords on,

The Heliand, line 3062:

- Sâlig bist thu Sîmon, quað he, sunu Ionases; ni mahtes thu that selbo gehuggean

- Blessed are you Simon, he said, son of Jonah; for you did not see that yourself (Matthew 16, 17).

This leads to a less dense style, no doubt closer to everyday language, which has been interpreted both as a sign of decadent technique from ill-tutored poets and as an artistic innovation giving scope for additional poetic effects. Either way, it signifies a break with the strict Sievers typology.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bostock, J.K. 1976. "Appendix on Old Saxon and Old High German Metre" A Handbook on Old High German Literature. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198153924

- Cable, Thomas. 1991. The English Alliterative Tradition. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812230635

- Fulk, Robert D. 1992. A History of Old English Meter. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780585196909

- Godden, Malcolm R. 1992. "Literary Language" in The Cambridge History of the English Language. edited by Richard M. Hogg (ed.)., 490–535. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521807586

- Russom, Geoffrey. 1998. Beowulf and Old Germanic Metre. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511002793

- Sievers, Eduard. 1893. Altgermanische Metrik. Niemeyer. OCLC 79113889

- Wise, Dennis (ed.). 2023. Speculative Poetry and the Modern Alliterative Revival: A Critical Anthology. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-1683933298

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.