Difference between revisions of "Zao Shen" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

({{Contracted}}) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{started}} | + | {{started}}{{Contracted}} |

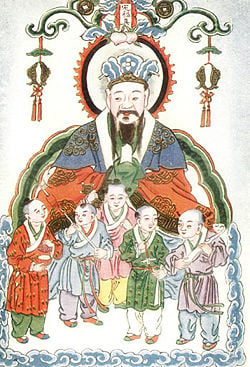

[[Image:Kitchen_god_drawing.png|thumbnail|right|150px|Zao Jun - God of the Kitchen]] | [[Image:Kitchen_god_drawing.png|thumbnail|right|150px|Zao Jun - God of the Kitchen]] | ||

Revision as of 15:01, 23 October 2007

In Chinese folk religion and Chinese mythology, the Kitchen God, named Zao Jun (Chinese: 灶君; pinyin: Zào Jūn; literally "stove master") or Zao Shen (Chinese: 灶神; pinyin: Zào Shén; literally "stove god"), is the most important of a plethora of Chinese domestic gods (gods of courtyards, wells, doorways, etc.). In this religio-mythic complex, it is believed that, in the days leading up to Chinese New Year, the god returns to Heaven to submit his annual report report on the family members' activities to the Jade Emperor (Yu Huang), who rewards or punishes the household accordingly.

Mythological Accounts

The cult of Zao Jun has been an active part of popular Chinese religion since at least the 2nd century B.C.E. Though no definitive sources exist, there are many[1] popular accounts describing the events leading up to the god's apotheosis.

In the most popular, it is suggested that he was once a mortal man named Zhang Dan (張單) (also known as Zhang Ziguo 張子郭), who was married to a virtuous woman. Unfortunately, Zhang Dan became utterly entranced with a young trollop, and, in his smitten state, sent his wife back to her parents in order to be with this exciting new woman. From that day on, however, Heaven afflicted him with ill-fortune in order to punish him for cruelty and thoughtlessness: specifically, he was struck blind, the young girl abandoned him, and he had to resort to begging to support himself.

While begging for alms one day, he unknowingly happened to pass the home of his former wife. Despite Zhang's shoddy treatment of her, the kind woman took pity on him and invited him in, where she tended to him lovingly and cooked him a meal of his favorite dishes. The foolish man was then utterly overcome by pain and self-pity as he realized the depth of his error, and he began to weep bitterly as he told the woman about his mistreatment of his caring wife. Hearing him apologize, Zhang's former companion urged him to open his eyes, at which point his vision was miraculously restored! Recognizing his benefactress as his abandoned wife, he was overcome with shame and threw himself into the kitchen hearth, not realizing that it was lit.

His wife tried to save him but he was utterly consumed by the fire, leaving her holding one of his dismembered legs. The devoted woman then lovingly created a shrine to her former husband above the fireplace where he died, which began Zao Jun's association with the stove in Chinese homes. As an etymological aside, a fire poker is still sometimes called Zhang Dan's Leg to this day.[2]

Alternatively, Zao Jun was a man so poor he was forced to sell his wife. Years later, he unwittingly became a servant in the house of her new husband. Taking pity on the destitute man, she baked him some cakes into which she had hidden money, but he failed to notice and sold them for a pittance. When he realized what he had done, he took his own life in despair. In both stories, Heaven takes pity on the foolish husbands and, instead of becoming a vampiric Jiang Shi (the usual fate of suicides), they are invested with the posting of kitchen god and allowed to be reunited with their lost loves.

In addition to the stories describing the origin of the Stove God as a deity, the mythic corpus also contains a popular tale about the first instance of a sacrifice to the kitchen god. In it, the god grants a Daoist magician named Li Shaojun two invaluable boons: eternal youth and freedom from the need for sustenance. In a fit of hubris, the young spiritual master appeared before emperor Xiao Wudi (140-86 B.C.E.) and promised him the same magical abilities if he offered sacrifice to Zao Shen. Though the ruler considered ignoring this request, he is reported to have been visited in a dream by the god, who convinced him that Magician Li was reputable. In hopes of achieving immortality, the emperor consented to offer sacrifice to the god. Unfortunately, the desired response was not achieved and Li was eventually killed for wasting his majesty's time. Regardless of these inauspicious beginnings, the emperor's sacrifice was still seen as an important religious milestone, with offerings to the Stove God playing an ever-increasing role in Chinese religiosity from Magician Li's time to the present.[3]

Worship and Customs

In a traditional Chinese household, the stove area was adorned with a paper effigy of Zao Jun (who was understood to analyze everything that transpires in the home) and his wife (who acts as his scribe), a pair of deities that document all of the year's happenings and reports them back to Yu Huang. This important (and somewhat daunting) responsibility has greatly increased the spiritual charisma of his office, such that many devout families make offerings of food and incense to the god on his birthday (the third day of the eighth lunar month),

<>

and also on the twenty third day of the twelfth lunar month when he returns to Heaven to give his New Year's report, on this day also the lips of Zao Jun's paper effigy may be smeared with honey to sweeten his words to Yu Huang (or keep his lips stuck together). After this the effigy will be burnt to be replaced by a new one on New Year's day and firecrackers are lit to speed him on his way to heaven. If the household has a statue or a nameplate of Zao Jun it will be taken down and cleaned on this day for the new year.[4]

a tradition is still widely practiced in China[5] and abroad.[6]

The judgment itself, and the concomitant modification of mortal fates, is accomplished by the Jade Emperor. His verdict is determined by the testimony of the Stove God, a humble deity who lives in the family's kitchen for the entirety of the year, witnessing each filial acts and minor transgression. As a result, one prominent New Year's Eve ritual involves bribing the Kitchen God with sweets (which are understood to either figuratively "sweeten his tongue" or to literally glue his lips shut).[7]

Zao Jun in Literature

In keeping with her thematic Zao Jun's story is interwoven with a feminist spin into the protagonist's story in Amy Tan's novel The Kitchen God's Wife.

Notes

- ↑ Werner notes that there are over "forty different stories of the origin of the Kitchen-god and of the men deified to take this responsible position." Specifically, he enumerates the following contenders: "an old female cook, who in early times specialized in cooking; a saint of antiquity, noted for his virtuous life; Yen Ti (Shen Nung) on account of his predilection for fire; Huang Ti, who was the first to erect stoves; Chung Li; Wu Hui; Su Chi-Li and his wife Wang-shih; a goddess named Chi; a god named Shan Tzukuo, who when a man, died on the day jen, on which day, therefore, stoves must not be erected; a beautiful maiden named Kuei; Chang Tan, named Tzu-kuo, whose wife was Ch'ing-chi; he is also referred to by the name of Jang-tzu; an old woman of unknown origins who lived on K'un-lun Shand, the K'un-lun Mountians, and was deputed by the seven rulers of the Pole Star to govern human beings; etc" (520).

- ↑ Shuhmacher and Woerner, 382; Werner, 520; Goodrich 40-41.

- ↑ Werner, 519; Shuhmacher and Woerner, 382.

- ↑ Chard, 13, 17; Newell, 64 ff 5.

- ↑ Goodrich, 31-41; Hung (2000).

- ↑ Newell (1989).

- ↑ Chard, 13, 17; Newell, 64 ff 5.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chard, Robert L. "Rituals and Scriptures of the Stove Cult." Ritual and Scripture in Chinese Popular Religion: Five Studies. Publications of the Chinese Popular Culture Project 3. Berkeley, CA: Chinese Popular Culture Project, 1995. ISBN 0962432733.

- Goodrich, Anne S. Peking Paper Gods: A Look at Home Worship. Monumenta Serica Monograph Series XXIII. Nettetal: Steyler-Verlag, 1991. ISBN 3-8050-0284-X.

- Newell, Venetia. "A Note on the Chinese New Year Celebration in London and Its Socio-Economic Background." Western Folklore 48:1 (January 1989). 61-66.

- Shuhmacher, Stephan and Gert Woerner (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion: Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Zen. Boston: Shambala, 1994. ISBN 0877739803.

- Werner, E.T.C. "Jade Emperor" in A Dictionary of Chinese Mythology. Wakefield, NH: Longwood Academic, 1990. 341-352. ISBN 0-89341-034-9.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.