William Penn

William Penn (October 14, 1644 – July 30, 1718) founded the Province of Pennsylvania, the British North American colony that became the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The democratic principles that he set forth served as an inspiration for the United States Constitution. Ahead of his time, Penn also published a plan for a United States of Europe, "European Dyet, Parliament or Estates." Penn has been described as America's first great champion for liberty and peace.[1] His colony gave equal right to people from different races and religions. He insisted that women were equal to men. He negotiated peace treaties with native Americans. He was imprisoned six times for his religious convictions. He gave his colony a written constitution, and humane laws. At the time, Pennsylvania was the only place under British jurisdiction where Roman Catholics were legally allowed to worship. It has been said that what Penn himself called his "holy experiment" sowed the seeds on which the United States would be built. He declared, "There may be room there for such a Holy Experiment. For the Nations want a precedent and my God will Make it the Seed of a Nation. That an example may be set up to the Nations. That we may do the thing that is truly wise and just."[2] Penn's ideas about peace diplomacy may even have inspired the founding of the United Nations.

Religious beliefs

Although born into a distinguished Anglican family and the son of Admiral Sir William Penn, Penn joined the Religious Society of Friends or Quakers at the age of 22. The Quakers obeyed their "inner light," which they believed to come directly from God, refused to bow or take off their hats to any man, and refused to take up arms. Penn was a close friend of George Fox, the founder of the Quakers. These were times of turmoil, just after Cromwell's death, and the Quakers were suspect, because of their principles which differed from the state imposed religion and because of their refusal to swear an oath of loyalty to Cromwell or the King (Quakers obeyed the command of Christ to not swear, Matthew 5:34).

Penn's religious views were extremely distressing to his father, Admiral Sir William Penn, who had through naval service earned an estate in Ireland and hoped that Penn's charisma and intelligence would be able to win him favor at the court of Charles II. In 1668 he was imprisoned for writing a tract (The Sandy Foundation Shaken) which attacked the doctrine of the trinity.

"If thou wouldst rule well, thou must rule for God, and to do that, thou must be ruled by him...Those who will not be governed by God will be ruled by tyrants."—William Penn

Penn was a frequent companion of George Fox, the founder of the Quakers, traveling in Europe and England with him in their ministry. He also wrote a comprehensive, detailed explanation of Quakerism along with a testimony to the character of George Fox, in his Introduction to the Journal of George Fox.

Persecutions

Penn was educated at Chigwell School, Essex where he had his earliest religious experience. Later, his religious views effectively exiled him from English society—he was sent down (expelled) from Christ Church, Oxford for being a Quaker, and was arrested several times. Among the most famous of these was the trial following his arrest with William Meade for preaching before a Quaker gathering. Penn pleaded for his right to see a copy of the charges laid against him and the laws he had supposedly broken, but the judge, the Lord Mayor of London, refused—even though this right was guaranteed by the law. Despite heavy pressure from the Lord Mayor to convict the men, the jury returned a verdict of "not guilty." The Lord Mayor then not only had Penn sent to jail again (on a charge of contempt of court), but also the full jury. The members of the jury, fighting their case from prison, managed to win the right for all English juries to be free from the control of judges and to judge not just the facts of the case, but the law itself. This case was one of the more important trials that shaped the future concept of American freedom (see jury nullification). The persecution of Quakers became so fierce that Penn decided that it would be better to try to found a new, free, Quaker settlement in North America. Some Quakers had already moved to North America, but the New England Puritans, especially, were as negative towards Quakers as the people back home, and some of them had been banished to the Caribbean.

The founding of Pennsylvania

In 1677, Penn's chance came, as a group of prominent Quakers, among them Penn, received the colonial province of West New Jersey (half of the current state of New Jersey). That same year, two hundred settlers from the towns of Chorleywood and Rickmansworth in Hertfordshire and other towns in nearby Buckinghamshire arrived, and founded the town of Burlington, New Jersey. Penn, who was involved in the project but himself remained in England, drafted a charter of liberties for the settlement. He guaranteed free and fair trial by jury, freedom of religion, freedom from unjust imprisonment and free elections.

King Charles II of England had a large loan with Penn's father, after whose death, King Charles settled by granting Penn a large area west and south of New Jersey on March 4, 1681. Penn called the area Sylvania (Latin for woods), which Charles changed to Pennsylvania in honor of the elder Penn. Perhaps the king was glad to have a place where religious and political outsiders (like the Quakers, or the Whigs, who wanted more influence for the people's representatives) could have their own place, far away from England. One of the first counties of Pennsylvania was called Bucks County named after Buckinghamshire (Bucks) in England, where the Penn's family seat was, and from whence many of the first settlers came.

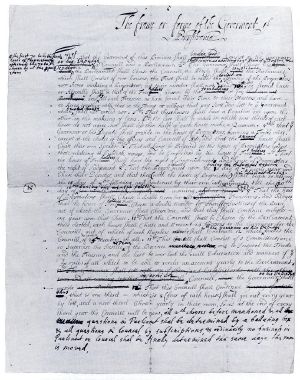

Although Penn's authority over the colony was officially subject only to that of the king, through his Frame of Government of Pennsylvania he implemented a democratic system with full freedom of religion, fair trials, elected representatives of the people in power, and a separation of powers—again ideas that would later form the basis of the American constitution. He called Pennsylvania his "holy experiment" and from it, he hoped, a nation based on justice would grow. The freedom of religion in Pennsylvania (complete freedom of religion for everybody who believed in God) brought not only English, Welsh, German and Dutch Quakers to the colony, but also Huguenots (French Protestants), Mennonites, Amish, and Lutherans from Catholic German states. He insisted on the equality of women.

Penn had hoped that Pennsylvania would be a profitable venture for himself and his family. Penn marketed the colony throughout Europe in various languages and, as a result, settlers flocked to Pennsylvania. Despite Pennsylvania's rapid growth and diversity, the colony never turned a profit for Penn or his family. In fact, Penn would later be imprisoned in England for debt and, at the time of his death in 1718, he was penniless.

From 1682 to 1684 Penn was, himself, in the Province of Pennsylvania. After the building plans for Philadelphia ("Brotherly Love") had been completed, and Penn's political ideas had been put into a workable form, Penn explored the interior. He befriended the local Indians (primarily of the Leni Lenape (the Delaware) tribe), and ensured that they were paid fairly for their lands. Penn even learned several different Indian dialects in order to communicate in negotiations without interpreters. Penn introduced laws saying that if a European did an Indian wrong, there would be a fair trial, with an equal number of people from both groups deciding the matter. His measures in this matter proved successful: even though later colonists did not treat the Indians as fairly as Penn and his first group of colonists had done, colonists and Indians remained at peace in Pennsylvania much longer than in the other English colonies.

Penn began construction of Pennsbury Manor, his intended country estate in Bucks County on the right bank of the Delaware River, in 1683.

Peace Negotiations

Penn also made a treaty with the Indians at Shackamaxon (near Kensington in Philadelphia) under an elm tree. Penn chose to acquire lands for his colony through business rather than conquest. He paid the Indians 1200 pounds for their land under the treaty, an amount considered fair. Voltaire praised this "Great Treaty" as "the only treaty between those people [Indians and Europeans] that was not ratified by an oath, and that was never infringed." Many regard the Great Treaty as a myth that sprung up around Penn. However, the story has had enduring power. The event has taken iconic status and is commemorated in a frieze on the United States Capitol.

Penn as a Peace Maker

In 1693, in his Present and Future Peace of Europe, Penn advocated the use of negotiation and diplomacy to prevent or end war. This has been described as a "prototype of the United Nations, which acknowledges this legacy by celebrating UN Day on Penn's birthday (October 24)".[3]

Final Years

Penn visited America once more, in 1699. In those years he put forward a plan to make a federation of all English colonies in America. There have been claims that he also fought slavery, but that seems unlikely, as he owned and even traded slaves himself. However, he did promote good treatment for slaves, and other Pennsylvania Quakers were among the earliest fighters against slavery.

Penn had wished to settle in Philadelphia himself, but financial problems forced him back to England in 1701. His financial advisor, Philip Ford, had cheated him out of thousands of pounds, and he had nearly lost Pennsylvania through Ford's machinations. The next decade of Penn's life was mainly filled with various court cases against Ford. He tried to sell Pennsylvania back to the state, but while the deal was still being discussed, he was hit by a stroke in 1712, after which he was unable to speak or take care of himself.

Penn died in 1718 at his home in Ruscombe, near Twyford in Berkshire, and was buried next to his first wife in the cemetery of the Jordans Quaker meeting house at Chalfont St Giles in Buckinghamshire in England. His family retained ownership of the colony of Pennsylvania until the American Revolution.

Legacy

Penn's belief in religious liberty and in the equal rights of all were destined to become part of the consciousness of the nation that arose from the original English colonies, including Pennsylvania. It is fitting that it was in Philadelphia that the United States Constitution was adopted on September 17, 1787, by the Constitutional Convention. The founding fathers of the United States, though, did not fully adopt Penn's ideals by excluding Indians and women and non-Whites from the State they founded. It would not be until much later that the seed he planted would mature yet it can be claimed that, as William Wistar Comfort said, "more than any other individual founder or colonist" it was Penn who has "proved to be the chosen vessel through which the stream of demand for respect for individual rights was to flow so richly into" America's "reservoir of precious ideals".[3]

Posthumous honors

On November 28, 1984, Ronald Reagan, upon an Act of Congress by Presidential Proclamation 5284 declared William Penn and his second wife, Hannah Callowhill Penn, each to be an Honorary Citizen of the United States.

There is a widely told, perhaps apocryphal, story that at one time George Fox and William Penn met. At this meeting William Penn expressed concern over wearing a sword (a standard part of dress for people of Penn's station), and how this was not in keeping with Quaker beliefs. George Fox responded, "Wear it as long as thou canst." Later, according to the story, Penn again met Fox, but this time without the sword; Penn said, "I have taken thy advice; I wore it as long as I could."

There is a statue of William Penn on top of the City Hall building of Philadelphia, sculpted by Alexander Milne Calder. At one time, there was a gentlemen's agreement that no building should be higher than Penn's statue. One Liberty Place was the first of several buildings in the late 1980s to be built higher than Penn. The statue is referenced by the so-called Curse of Billy Penn.

A common misconception is that the smiling Quaker shown on boxes of Quaker Oats is William Penn. The Quaker Oats Company has stated that this is not true.

Notes

- ↑ Jim Powell, "William Penn: America's First Great Champion for Liberty and Peace" William Penn: America's First Great Champion for Liberty and Peace Retrieved August 18, 2007

- ↑ "General Assembly of Pennsylvania: Senate Resolution No 189," 2005, General Assembly of Pennsylvania: Senate Resolution No 189 Retrieved August 18, 2007

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Penn's Holy Experiment: The Seed of a Nation," Penn's Holy Experiment: the Seed of a Nation Retrieved August 18, 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dunn, Richard S. and Mary Maples Dunn. The World of William Penn. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 9780812280203

- Fields, Darrell. The Seed of a Nation: Reconciling with the Birth of America. Mechanicsburg, PA: Covenant Press, 2000. ISBN 9780967851808

- Geiter, Mary K. William Penn. Harlow, England; NY: Longman, 2000. ISBN 9780582299009

- Soderlund, Jean R. William Penn and the founding of Pennsylvania, 1680-1684: a documentary history. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1983. ISBN 9780812278620

- Wildes, Harry Emerson. William Penn. NY: Macmillan, 1974. ISBN 9780026285704

External links

All links retrieved May 11, 2023.

- The LIFE of William Penn by M.L. Weems, 1829. Full-text free to read and search version of William Penn's biography from 1829 original published in Philadelphia.

- William Penn, Visionary Proprietor by Tuomi J. Forrest, at the University of Virginia.

- William Penn, America's First Great Champion for Liberty and Peace by Jim Powell.

- William Penn by Bill Samuel.

- Hidden London Penn in the Tower.

- "Pennsylvania's Anarchist Experiment: 1681-1690," Prof. Murray N. Rothbard, excerpt from Conceived in Liberty, Vol. 1 (Auburn, Alabama: The Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1999).

Penn's works online

- Some Fruits of Solitude In Reflections And Maxims (1682)

- Frame Of Government Of Pennsylvania (1682) (Excerpts)

- Letter to his wife, Gulielma (1682)

- Early Quaker writings contains several documents by Penn and his wife.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.