Value added tax

The Value Added Tax ( VAT ) taxes all business profit and labor. Profit being gross receipts minus all business expenses including the 'tax' on labor which is considered a cost of doing business. Profit and labor could be lumped together by subtracting all other business expenses from gross receipts and then taxing the remainder at a uniform VAT tax rate.

The cost of materials, subcomponents, tools, equipment, facilities, supplies, etc, and any services purchased from other businesses isn't taxed (again) under the VAT. Those purchases would have already been subjected to the VAT by the supplying businesses.

History of VAT as a Consumption Tax

The VAT was invented by a French economist in 1954. Maurice Lauré, joint director of the French tax authority, the Direction générale des impôts, as taxe sur la valeur ajoutée (TVA in French) was first to introduce VAT with effect from 10 April 1954 for large businesses, and extended over time to all business sectors. In France, it is the most important source of state finance, accounting for approximately 45% of state revenues.

The VAT is usually collected by the tax credit method; each firm applies the tax rate to its taxable sales, but is allowed a credit for value-added tax paid on its purchases of goods and services for business use, including the tax paid on purchases of capital equipment under a consumption-type value-added tax. As a result, the only tax for which no credit would be allowed would be that collected on sales made to households, rather than to businesses.

Since the sum of the values added at all stages in the production and distribution of a good are equal to the retail selling price of the good, the revenue base of a retail sales tax and a value-added tax with the same coverage are theoretically identical, and a given tax rate will yield the same amount of tax revenue under either approach and under equal conditions of implementation, e.g., no exceptions, exemptions, etc.

VAT’s minimal differences from the ( Retail ) Sales Tax

Thus, despite its multistage character, a value-added tax is very much like a retail sales tax in that it is a tax on expenditures by consumers or, in other words, it is just another type of consumption tax.

Retail sales tax, the familiar percentage tax on retail sales, is one type of consumption tax. Of the various forms of consumption taxes, the sales tax surely has the great advantage for most of tax-payers of eliminating the despotic power of the government over the life of every individual, as in the income tax, or over each business firm, as we shall see the VAT might do. Sales tax also does not distort the production structure as would the VAT, and it would not skew individual preferences as would specific excise taxes ( Rothbard, 1994 ).

The VAT consumption tax, proposed in the U.S., imposes a bit of hierarchical tax on the "value added" by each firm and business.

Here, instead of every individual, every business firm would be subjected to intense bureaucratic scrutiny, for each firm would be obliged to report its income and its expenditures, paying a designated tax on the net income.

This would tend to distort the structure of business. For one thing, there would be an incentive for uneconomic vertical integration, since the fewer the number of times a sale takes place, the fewer the imposed taxes. Also, as has been happening in European countries with experience of the VAT, a flourishing industry may arise in issuing phony vouchers, so that businesses can over-inflate their alleged expenditures, and reduce their reported value added.

Since the sum of the values added at all stages in the production and distribution of a good are equal to the retail selling price of the good, the revenue base of a retail sales tax and a value-added tax with the same coverage are theoretically identical, and a given tax rate will yield the same amount of tax revenue under either approach.

Thus, despite its multistage character, a value-added tax is very much like a retail sales tax in that it is a tax on expenditures by consumers.

But a sales tax, other things being equal, seems to be both simpler, less distorting of resources, and enormously less bureaucratic and despotic than the VAT. Indeed the VAT seems to have no clear advantage over the sales tax, except of course, if multiplying bureaucracy and bureaucratic power is considered a benefit ( ibid., 1994 ).

Example

ILLUSTRATION OF A RETAIL SALES TAX AND A VALUE-ADDED TAX (Tax Rate is 5 Percent)

Assumed Facts: Winery Grocery Store Total a. Sales………. .. .. 200 300 ** b. Purchases ….. … 0 200 ** c. Value added (a-b)….. 200 100 **

Calculation of Retail Sales Tax

d. Tax (5% of a, for grocer only) * 15 15

Calculation of Value-Added Tax e. Tax on sales (5% of a) 10 15 **

f. Credit for tax on purchases( 5% of b) 0 10 **

g. Net tax (e-f) 10 5 15 ___________________________________________________________________________

- Retail sales tax is collected only on retail sales by grocer; it

is not levied on sales by the winery.

- Not relevant for illustration

Several disadvantages of VAT

- Growth of government ( see also “Administrative Costs”):

The United States stands almost alone among the developed countries of the free world in not levying a national sales tax. Virtually all of the members of the European Economic Community (EEC) employ a national value-added tax. Of the twenty-three ( original ) members of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), only two countries—Japan and Turkey—use neither a value-added tax nor a general sales tax. In Canada, there is a bit similar national tax ---- apart from bewildering array of, by no means harmonized, provincial sales taxes --- called GST or General Sales tax.

The lack of a national sales tax ( e.g. VAT ) in the United States is reflected closely in the percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) devoted to public use in the United States and in other countries. In 1982 total tax revenues at all levels of government averaged 30.5 percent of GDP in the United States. The comparable figure for the EEC countries was 40.1 percent and for the countries of the OECD, exclusive of the United States, it was 37.1 percent.

In the United States, sales taxes (state and local) took approximately 6 percentage points less of GDP than in the EEC and in the OECD (exclusive of the United States). It is not only sales taxes that are lower in the United States; corporate income and social security taxes also are substantially lower in the figures suggest that even if a sales tax were initially imposed as a partial replacement for the income tax in a revenue-neutral change, public spending in the United States would eventually be greater with a national sales tax than without one.

- Regressivity:

A tax is regressive if the average tax rate falls with an increase in income, proportional if the average tax rate is constant, and progressive if the average tax rate rises with income. Simply put, low-income people pay a higher fraction of their income in taxes than wealthier people if the tax is regressive and a lower fraction if the tax is progressive.

A general sales tax --- as all types of consumption taxes inclusive of ( Retail ) sales tax ---- is often criticized as unfair to lower income individuals and families. There are two aspects to this equity argument:

( 1 ) The absolute burden of the tax on the lowest income groups, and the regressivity of the tax or the relatively higher burden of the tax at the lower income levels than at the higher.

Simultaneously,

( 2 ) There are several alternatives for lessening the burden of the tax on the poor. For those individuals and families that are above the poverty level of income and thus subject to the income tax, the regressivity of a sales tax can be offset through the adjustment of income tax rates or through non-refundable credits against the income tax.

- Effect on prices:

Assuming an accommodating monetary policy, a sales tax would almost certainly increase the price level by roughly the percentage it represents of consumption spending. That is, a 4 percent sales tax that applied to 75 percent of consumption expenditures would increase the general price level by about 3 percent.

Although this would be a one-time occurrence, not an annual increase, it might cause "ripples" of wage increases, because of cost-of-living adjustments ( ! ) and these could be reflected in further price increases. To the extent the sales tax replaced part of the income tax, there would be little offsetting reduction in prices or wages.

- Administrative costs:

Administration of a Federal value-added tax would require substantial additional resources. The Internal Revenue Service estimates that once the administrative program was fully phased in, the annual administrative costs would run about $700 million (at 1984 prices), or about 0.4 percent of revenues from a 10 percent broad-based value-added tax. To administer a value-added tax, the IRS would require approximately 20,000 additional personnel.

The Impossibility of Taxing Only Consumption

Having challenged the merits of the goal of taxing only consumption and freeing savings from taxation, we now proceed to deny the very possibility of achieving that goal, i.e., we maintain that a consumption tax will devolve, willy-nilly, into a tax on income and therefore on savings as well. In short, that even if, for the sake of argument, we should want to tax only consumption and not income, we should not be able to do so.

A positive way to go: VAT eliminating Personal and Corporate Taxes

One of the more interesting theoretical arguments for a VAT is that the new tax would improve economic performance by facilitating a reduction in other taxes. According to some advocates, the additional revenue generated by a VAT—$37 billion for every percentage point, according to the "Congressional Research Service15"—could be used to lower, or perhaps even eliminate, personal and corporate income taxes.

Hence, if the VAT was actually used to eliminate all income taxes, this theory would have considerable merit. There is no doubt that personal and corporate income taxes do more damage per dollar raised than a VAT would.

A national sales tax ( VAT ) thus should have several major advantages over the current combination of national income tax and states’ ( provincial ) taxes. If it were used to replace part ( or, eventually all ) of the income tax, a Federal sales tax would allow much lower ( or none at all ) income tax rates. By taking pressure off the definition and measurement of taxable income, a sales tax would help reduce income tax avoidance and evasion as well as lessen the incentive to shelter income from the income tax. Based on consumption, rather than income, a national sales tax ( e.g. VAT ) would not discriminate against saving the way the income tax does.

Accordingly, it may increase the level of private saving and generate a corresponding increase in capital formation and economic growth. A broad-based sales tax would almost certainly distort economic choices less than the income tax does. In contrast to the income tax, it would not discourage capital-intensive methods of production or risk taking and it would be neutral with regard to other major revenue sources.

At the state level, this system of exemption certificates applies only to goods purchased for resale or goods that become component parts or physical ingredients of produced goods; other purchases, such as machinery and equipment, are only exempt if specifically provided in the state statute. The end result is that not all business purchases are free of retail sales tax; about 20 percent of sales tax revenue is from taxing business purchases.

Another important advantage of the value-added form of sales tax is the fact that tax is collected as products move from stage to stage in the production-distribution process. Thus by the time a product reaches the retail stage, much of its total value has already been taxed.

To summarize: Theoretically, a VAT ( or national sales tax ) would be acceptable if it were combined with ratification of a constitutional amendment that permanently prohibits both the personal and corporate income taxes, however unlikely this scenario is.

( NOTE: In fact, as yet no nation has ever implemented a VAT ( or a national sales tax) and used the money to eliminate all income taxes. )

Taxing Income vs. Consumption

The Income Tax places taxes on business profit and on the employee's wages which the business withholds from the employee in trust for the government. The VAT ( i.e. consumption tax ) taxes business profit and total employee wages directly. Collection of employee wage taxes, in the case of Income Tax, is called "withholding" and in the VAT it's a direct "labor tax" on the business.

With the Income Tax, a $100 wage may have $10 tax withheld by the employer leaving $90 for the employee. With the VAT, the employee would be paid $90 and the employer would be subject to a $10 labor tax. Other than how it's perceived, there appears to be no difference between a Value Added Tax and a truly flat, non-discriminatory Income Tax that's collected at the source of income.

Orthodox neoclassical economics has long maintained that, from the point of view of the taxed themselves, an income tax is "better than" an excise tax on a particular form of consumption, since, in addition to the total revenue extracted, which is assumed to be the same in both cases, the excise tax weights the levy heavily against a particular consumer good.

An excise tax, say, on whiskey or on movie admissions, will intrude directly on no one's life and income, but only into the sales of the movie theater or liquor store. It is quite feasible that, in evaluating the "superiority" or "inferiority" of different modes of taxation, even the most determined imbiber or moviegoer would cheerfully pay far higher prices for whiskey or movies than neoclassical economists contemplate, in order to avoid the long arm of the IRS ( NOTE [1] ).

The problem of first decade of 21st century is a fast increasing price of gasoline and its excessive taxation. As this is, in most developed countries, one of the necessities of life ( just like the foodstuff ) except its trend is several-fold steeper, one of the solution would be to nullify any excise tax on gasoline for “commuters” or introduce, for instance, a personal exemption type of value-added. Under this approach, which would differ substantially from a conventional value-added tax, workers would be considered to be "sellers" of labor services and would be subject to a value-added tax, but they could not take credits for value-added tax on their purchases of basic consumption goods, such as gasoline. Employers would be allowed a credit for the taxes "charged" by employees on their wages.

However, the only coherent argument offered by advocates of consumption against income taxation is that of Irving Fisher, based on suggestions of John Stuart Mill. Fisher argued that, since the goal of all production is consumption, and since all capital goods are only way-stations on the way to consumption, the only genuine income is consumption spending.

The conclusion is quickly drawn that therefore only consumption income, not what is generally called "income," should be subject to tax ( Rothbard, 1977, pp. 98–100.)

The market, in short, knows all about the productive power of savings for the future, and allocates its expenditures accordingly. Yet even though people know that savings will yield them more future consumption, why don't they save all their current income?

Clearly, because of their time preferences for present as against future consumption. These time preferences govern people's allocation between present and future. Every individual, given his money "income"---defined in conventional terms---and his value scales, will allocate that income in the most desired proportion between consumption and investment. Any other allocation of such income, any different proportions, would therefore satisfy his wants and desires to a lesser extent and lower his position on his value scale.

It is therefore incorrect to say that an income tax levies an extra burden on savings and investment; it penalizes an individual's entire standard of living, present and future. An income tax does not penalize saving per se any more than it penalizes consumption.

"......Having challenged the merits of the goal of taxing only consumption and freeing savings from taxation, we can now proceed to deny the very possibility of achieving that goal, i.e., we maintain that a consumption tax will devolve, willy-nilly, into a tax on income and therefore on savings as well. In short, that even if, for the sake of argument, we should want to tax only consumption and not income, we should not be able to do so...." ( Rothbard, 1977 ).

Numerical example

We can see it on a simple example. Let us take a, seemingly straightforward, tax plan that would exempt saving and tax only consumption. Let us take Mr. Jones, who earns an annual income of $100,000. His time preferences lead him to spend 90 percent of his income on consumption, and save-and-invest the other 10 percent. On this assumption, he will spend $90,000 a year on consumption, and save-and-invest the other $10,000.

Let us assume now that the government levies a 20 percent tax on Jones's income, and that his time-preference schedule remains the same. The ratio of his consumption to savings will still be 90:10, and so, after-tax income now being $80,000, his consumption spending will be $72,000 and his saving-investment $8,000 per year ( NOTE [2] ).

Suppose now that instead of an income tax, the government follows the Irving Fisher scheme and levies a 20 percent annual tax on Jones's consumption. Fisher maintained that such a tax would fall only on consumption, and not on Jones's savings. But this claim is incorrect, since Jones's entire savings-investment is based solely on the possibility of his future consumption, which will be taxed equally.

Since future consumption will be taxed, we assume, at the same rate as consumption at present, we cannot conclude that savings in the long run receives any tax exemption or special encouragement. There will therefore be no shift by Jones in favor of savings-and-investment due to a consumption tax ( NOTE [3]).

In sum, any payment of taxes to the government, whether they be consumption or income, necessarily reduces Jones's net income. Since his time preference schedule remains the same, Jones will therefore reduce his consumption and his savings proportionately. The consumption tax will be shifted by Jones until it becomes equivalent to a lower rate of tax on his own income.

If Jones still spends 90 percent of his net income on consumption, and 10 percent on savings-investment, his net income will be reduced by $15,000, instead of $20,000, and his consumption will now total $76,000, and his savings-investment $9,000. In other words, Jones's 20 percent consumption tax will become equivalent to a 15 percent tax on his income, and he will arrange his consumption-savings proportions accordingly (NOTE [4]).

Graphical example

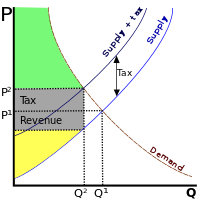

A VAT, like most taxes, distorts what would have happened without it. Because the price for someone rises, the quantity of goods traded decreases. Correspondingly, some people are worse off by more than the government is made better off by tax income . That is, more is lost due to supply and demand shifts than is gained in tax. This is known as a deadweight loss. The income lost by the economy is greater than the government's income; the tax is inefficient. The entire amount of the government's income (the tax revenue) may not be a deadweight drag, if the tax revenue is used for productive spending or has positive externalities - in other words, governments may do more than simply consume the tax income. While distortions occur, consumption taxes like VAT are often considered superior because they distort incentives to invest, save and work less than most other types of taxation - in other words, a VAT discourages consumption rather than production.

In the above diagram,

- Deadweight loss: the area of the triangle formed by the tax income box, the original supply curve, and the demand curve

- Government's tax income: the grey rectangle that says "tax"

- Total consumer surplus after the shift: the green area

- Total producer surplus after the shift: the yellow area

History of VAT adverse effect in EU

- Expands the cost of government. Countries with VATs have a much heavier total tax burden than those without VATs. Before the creation of VATs, the burden of taxation in Europe was not that much larger than it was in the United States. However, since the late 1960s, when countries in Europe began to adopt VATs, Europe’s aggregate tax burden has increased by about 50 percent while the U.S. tax burden has remained relatively constant ( Bickley, 2005.)

- Inadvertently increases income tax rates. One of the main arguments for the VAT is that it is a less destructive way to raise revenue. This is theoretically true, but irrelevant. In the real world, the VAT has been used as an excuse to increase income taxes as a way to maintain “distributional neutrality.” Indeed, income taxes in Europe today are higher than they were when VATs were implemented.

- Slows economic growth and destroy jobs. A VAT undermines economic growth for two reasons. First, it reduces incentives to engage in productive behavior by driving a larger wedge between pre-tax income and post-tax consumption. Second, it facilitates larger government and the concomitant transfer of resources from the productive sector of the economy to the public sector, diminishing economic efficiency ( Engen, 1992.)

EU legal directives about VAT

The VAT Directive 2006/112/EC of 28 November 2006 (Official Journal L 347, 11.12.2006, p.1) provides in its Articles 93 to 130 and Annex III and IV a legal framework for the application of VAT rates in Member States. Member States have made and continue to make wide use of the possibilities offered within this framework; as a result, the situation is in practice disparate and complex. The basic rules are simple:

- Supplies of goods and services subject to VAT are normally subject to a standard rate of at least 15%.

- Member States may apply one or two reduced rates of not less than 5% to goods and services enumerated in a restricted list.

Further on, from 2008 forward, revenues will now be reaped by the country in which the consumer is located rather than the one in which the company providing the service is established. The aim of the reform is to minimise the administrative burden for companies engaged in cross-border operations and prevent distortions of competition between countries operating different VAT rates.

VAT in EU ( vs. USA ) statistics

VATs Associated with Higher Aggregate Tax Burdens

“Taxes as a Percent of GDP”:

- 1967 USA.... 25.3% / EU-15....25.5%

- 2002 USA.... 29.8% / EU-15....42.1%

Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Revenue Statistics, 1965–2003 (Paris: OECD Publications, 2004)

Burden of Government ( Spending and Debts ): the U.S. vs. Europe

“Government Spending as Percent of GDP in 2004”:

- USA.... 35.7% / EU-15....47.6%

“Government Debt as Percent of GDP in 2004”:

- USA....26.6% / EU-15....50.1%

Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD

in Figures, 2004 ed., at www1.oecd.org/publications/e-book/0104071E.pdf (May 9, 2005).

Conclusion

Theory vs. Actual state of affair

There are obviously two contradicting views on the very basics of VAT. If the VAT was actually used to eliminate all income taxes, this theory would have considerable merit. There is no doubt that personal and corporate income taxes do more damage per dollar raised than a VAT would ( Guseh, 1977.)

However, no nation has ever implemented a VAT (or a national sales tax) and used the money to eliminate all income taxes.

Indeed, no government in the world—national, state, provincial, county, or city—has taken this step. No government has even eliminated just one of the two forms of income taxation (personal and corporate). The VAT always has been imposed in addition to existing personal and corporate income taxes ( Grier, 1989.)

Faced with this overwhelming real-world evidence, VAT advocates sometimes argue that the tax at least could be used to lower taxes on personal and corporate income. Just like the total replacement hypothesis, this partial-replacement hypothesis is an interesting theory, but it is equally implausible. All available statistics show that the aggregate tax burden on income and profits (a measure of the tax on personal and corporate income) has fallen slightly in the United States, but it has risen significantly in the European Union, and this increased tax burden on productive activity took place after VATs became ubiquitous ( Genetski, 1988.)

Classical Economics’ Considerations

Let us seek a help to this conundrum from a genuine free-market approach of Jean-Baptiste Say, who contributed considerably more to economics than Say's law.

Say was under no illusion that taxation is voluntary nor that government spending contributes productive services to the economy. Say pointed out that, in taxation, "……The government exacts from a taxpayer the payment of a given tax in the shape of money. To meet this demand, the taxpayer exchanges part of the products at his disposal for coin, which he pays to the tax-gatherers….." (Say 1880).

Eventually, the government spends the money on its own needs, so that ".....in the end . . . this value is consumed; and then the portion of wealth, which passes from the hands of the taxpayer into those of the tax-gatherer, is destroyed and annihilated....."( ibid. )

Note, that as in the case of many economists, such as Murray Rothbard, Say sees that taxation creates two conflicting classes, the taxpayers and the tax-gatherers.

"...Were it not for taxes, the taxpayer would have spent his money on his own consumption. As it is, the state . . . enjoys the satisfaction resulting from that consumption….."( ibid. ).

Taxation, then, for Say is the transfer of a portion of the national products from the hands of individuals to those of the government, for the purpose of meeting the public consumption of expenditure.” . . . It is virtually a burthen imposed upon individuals, either in a separate or corporate character, by the ruling power . . . for the purpose of supplying the consumption it may think proper to make at their expense…..”( ibid, p. 446 ).

But taxation, for Say, is not merely a zero-sum game. By levying a burden on the producers, he points out, taxes, over time, cripple production itself.

Writes Say: “…..Taxation deprives the producer of a product, which he would otherwise have the option of deriving a personal gratification from, if consumed . . . or of turning to profit, if he preferred to devote it to an useful employment. . . Therefore, the subtraction of a product must needs diminish, instead of augmenting, productive power……( ibid, p. 447 ).

J. B. Say's policy recommendation was crystal clear and consistent with his analysis and that of various comments on VAT: "…..The best scheme of [public] finance is, to spend as little as possible; and the best tax is always the lightest….."( ibid.,1880 ).

To this, there is nothing more to add.

References and Notes

- Bickley, James “A Value-Added Tax Contrasted with a National Sales Tax,” Congressional Research Service, March 23, 2005.

- Engen, Eric M. and Jonathan Skinner, “Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 4223, 1992.

- Genetski,Robert J. Debra J. Bredael, and Brian S. Wesbury, “The Impact of a Value-Added Tax on the U.S. Economy,” Stotler Economics, December 1988.

- Grier, Kevin B. and Gordon Tullock, “An Empirical Analysis of Cross-National Economic Growth, 1951–80,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 24, No. 2 (September 1989), pp. 259–276.

- Guseh, James S. “Government Size and Economic Growth in Developing Countries: A Political-Economy Framework,” Journal of Macroeconomics, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 1997), pp. 175–192.

- Kesselman, J., Keith Banting, and Ken Battle eds. 1994. “Public Policies To Combat Child Poverty: Goals and Options. A New Social Vision for Canada? Perspectives on the Federal Discussion Paper on Social Policy Reform. Kingston, CA: Queen’s University, School of Policy Studies. ISBN 0889116873.

- Kesselman, J. 1997. General Payroll Taxes: Economics, Politics, and Design. Toronto, CA: Canadian Tax Foundation. ISBN 0888081219.

- Rothbard, Murray. 1994. Consumption Tax : A Critique. Review of Austrian Economics. 7:2:75–90.

- Rothbard, Murray. 1977. Power and Market: Government and the Economy. Kansas City, KS: Sheed Andrews & McMeel. ISBN 0836207505.

- Rothbard, Murray N. 1988. Review of A. Chafuen, Christians for Freedom: Late Scholastic Economics. International Philosophical Quarterly. 28:112–14.

- Say, Jean-Baptiste A Treatise on Political Economy, 6th ed. (Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Heffelfinger, 1880, pp. 412–415, 446); see also Murray N. Rothbard, "The Myth of Neutral Taxation," Cato Journal, No.1,Fall 1981,pp. 551–54.

- Rothbard, Murray N. 1981. The Myth of Neutral Taxation. Cato Journal. 1:551–54.

Notes

- [1] It is particularly poignant, on or near any April 15, to contemplate the dictum of Father Navarrete, that "...the only agreeable country is the one where no one is afraid of tax collectors..."( Chafuen, Christians for Freedom, p. 73.) Also see Murray N. Rothbard, "Review of A. Chafuen, Christians for Freedom: Late Scholastic Economics," International Philosophical Quarterly 28 (March 1988),pp. 112–14.

For a fuller treatment, and a discussion of who is being robbed by whom, see Murray N. Rothbard, Power and Market: Government and the Economy, 2nd ed. (Kansas City: Sheed Andrews & McMeel, 1977, pp. 120–21)

- [2] We set aside the fact that, at the lower amount of money assets left to him, Jones's time preference rate, given his time preference schedule, will be higher, so that his consumption will be higher, and his savings lower, than we have assumed.

- [3] In fact, per note [2], supra, there will be a shift in favor of consumption because a diminished amount of money will shift the taxpayer's time preference rate in the direction of consumption. Hence, paradoxically, a pure tax on consumption will and up taxing savings more than consumption( Rothbard, Power and Market, pp. 108–11.)

- [4] lf net income is defined as gross income minus amount paid in taxes, and for Jones, consumption is 90 percent of net income, a 20 percent consumption tax on $100,000 income will be tantamount to a 15 percent tax on this income( see: ibid. )

The basic formula for the net income is:

N = G / ( 1+ t.c ),

where G = gross income, t = the tax rate on consumption, and c, consumption as percent of net income, are givens of the problem, and N = G – T by definition, where T is the amount paid in consumption tax.

External links

All LinksRetrieved December 12, 2007.

- VAT Related Services at the Open Directory Project

- VAT in INDIA

- What is VAT?: General overview

- An introduction to VAT

- German VAT

- VAT/GST sales tax rates around the world

- HM Revenue & Customs

- UK VAT Threshold Rates

- A Guide to the latest VAT news in the UK by PricewaterhouseCoopers

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.