Saul

Saul (or Sha'ul) (Hebrew: שָׁאוּל, meaning "given") was the first king of the ancient Kingdom of Israel. (Please add something about his approximate dates in the opening paragraph)

Described in the Bible (the first Book of Samuel) as a man of uncommon promise and valor, Saul united the tribes of Israel against the power of the Philistines, but lost the support of a key ally — namely Samuel, the powerful prophet and judge who had initially identified and anointed him as God's chosen leader. Despite subsequent military successes and a promising heir in his son Jonathan, Saul became a tragic figure. He was plagued by what the Bible describes as "an evil spirit from the Lord," and what psychologists would recognize as classic symptoms of manic-depression.

Much of the later part of Saul's reign was consumed by fighting against Israel's enemies on one hand and seeking to destroy his divinely-appointed successor, David, on the other. He died in battle soon after the death of his son Jonathan, leaving his lesser sons as heirs. Within a few decades, his rival, David, had brought Saul's former kingdom under his sway and taken his only surviving son into captivity.

It should be noted that the story of Saul is largely written and edited by biblical writers who favored the southern, or Davidic, kingdom of Judah. Our picture of Saul is therefore not an objective one. If his own supporters had written histories of his reign which survived intact, we would no doubt have a very different portrait from the current one.

Nativity and Youth

According to the Books of Samuel, Saul was the son of a man named Kish, and a member of the tribe of Benjamin. We are told little about Saul's youth other than that he was "an impressive young man without equal among the Israelites—a head taller than any of the others." (1 Sam. 9:2)

However, biblical scholars suggest that some of the details in the story of Saul's childhood may actually be found in the infancy narrative now attributed to Samuel. Evidence for this is found in the meaning of Saul's name and in the fact that the story of Samuel's infancy seems in some respects to describe that of a future king rather than a prophet.

The Hebrew version of Saul's name can mean, "lent," "asked for," or "given," and Samuel's mother Hanna seems to be making a pun on this word when she says to Eli the priest:

- The Lord has granted me what I asked [sha'al] of him. So now I give [sha'al] him to the Lord. For his whole life he will be given over [sha'al] to the Lord." (1 Sam: 27-28)

Moreover, the Song of Hannah, a psalm of praise expressing Hannah's response to the birth of her son, can more easily be interpreted as referring to her son as a monarch than a prophet or judge: "He [God] will give strength to his king and exalt the horn of his anointed." (1 Sam. 2:10)

Whether or not the biblical story of Samuel's childhood originally described that of Saul, the rabbinical tradition and the Bible itself are unanimous in portraying the young Saul as a lad of great promise. The Jewish Encyclopedia, summarizing the talmudic praise of Saul, says:

- He was extraordinarily upright as well as perfectly just. Nor was there any one more pious than he; for when he ascended the throne he was as pure as a child, and had never committed sin. He was marvelously handsome; and the maidens who told him concerning Samuel talked so long with him that they might observe his beauty the more.[1]

Appointment as King

The Bible gives a threefold account of how Saul came to be appointed as king. First, he is privately chosen by the Prophet Samuel and anointed as king. Second, he is re-anointed in public after a God confirms the choice by lottery. Finally, he is confirmed by popular acclaim after uniting the tribes of Israel in victorious battle. Modern biblical scholars, on the other hand, tend to view the accounts as distinct, representing at least two and possibly three separate traditions which were later woven into a single account.

- (1 Samuel 9:1-10:16) Saul travels with a servant to look for his father's she-asses, who have strayed. Leaving his home at Gibeah, they eventually wander to the district of Zuph, at which point Saul suggests abandoning their search. Saul's servant however, suggests that they should consult the local "seer" first. The seer (later identified as Samuel) offers hospitality to Saul when he nears the high place at Ramah, and later anoints him in private.

- (1 Samuel 10:17-24 and 12:1-5) Seeing that Samuel's sons were corrupt, the Israelites demand a king to rule and protect them. Samuel therefore assembles the people at Mizpah, and despite having strong reservations, obeys God's instruction to appoint a king. In this version, a lottery system is used to determine the choice. First the tribe of Benjamin is chosen, and then Saul. The seemingly unsuspecting Saul seeks to avoid his fate by hiding in the baggage. He is soon discovered, anointed, and publicly proclaimed. The text notes, however, that certain "troublemakers" grumble against the choice.

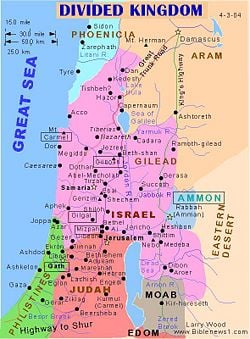

- (1 Samuel 11:1-11 and 11:15) In this story, Saul is living as a private landholder. He rises to the kingship by uniting the several tribes to relieve the people of Jabesh Gilead, who are being besieged by the Ammonites. After Saul gains victory, the people congregate at Gilgal, and acclaim Saul as king. (This account is portrayed in the text as a confirmation of Saul's already known kingship, but some scholars take the view that it describes a separate tradition about the origin of Saul's monarchy, which a later editor has characterized as a confirmation.)

In any case, the tribe of Benjamin was an unlikely choice for a king. Saul's own declaration "Am not I a Benjamite, of the smallest of the tribes of Israel?" (1 Sam. 9:21) betrays not only his own lack of confidence but also the fact that Benjamin was by this time a weak and despised part of the Israelite confederacy. Indeed, the final chapter of the Book of Judges speaks of the Israelites swearing that "Not one of us will give his daughter in marriage to a Benjamite." (Judges 21:1) Although this oath was later rescinded, there can be little doubt that the choice of a Benjamite as king would be problematic to many among the other tribes.

Saul's Victories

On the foundation of his fame in winning victory against the Ammonites, Saul amasses an army to throw off the Philistine yoke. Just before this battle, however, he has a serious falling out with Samuel. Samuel has instructed Saul to wait seven days for him at Gilgal. Saul does so, but as the hour approaches, his men begin to desert. When the appointed time comes and goes without Samuel appearing, Saul prepares for battle by offering sacrifice to God. Samuel soon arrives on the scene and condemns Saul, apparently for usurping the priestly role. Samuel withdraws his support from Saul and declares that God has chosen another to replace him. Deprived of Samuel's blessing, Saul's army has become small, numbering only around 600 men. The text portrays the Philistine army as vastly outnumbering the Israelites and also having superior weaponry due to their master of the art of metalworking while the Israelites use mostly flint and wood weapons.

Jonathan and a small group of courageous Israelites cleverly sneak into a Philistine outpost without Saul's knowledge to attack them from within, causing panic. However, trouble brews for the Israelites spiritually. Saul has vowed that his men will not eat until the battle is over, and Jonathan — who has not heard the vow — consumes wild honey. Nevertheless, the battle goes well. When the Israelites notice the chaos in the Philistine camp, Saul joins in the attack and the Philistines are driven out. However, some of his soldiers sin by eating plundered meat that has not been properly slaughtered.

Saul asks his priest, Ahijah, to use divination to ask God whether he should pursue the Philistines and slaughter them, but God gives no answer. Convinced that God's silence is due to someone's sin, Saul conducts a lottery and discovers Jonathan's sin of eating forbidden honey. Saul determines to slay Jonathan for his offense, but the soldiers come to Jonathan's defense. Saul relents, and he also cuts off his pursuit of the Philistines.

Despite the lack of a decisive conclusion in the war against the Philistines, the Bible states that he was an effective military leader.

- After Saul had assumed rule over Israel, he fought against their enemies on every side: Moab, the Ammonites, Edom, the kings of Zobah, and the Philistines. Wherever he turned, he inflicted punishment on them.

He was assisted in these efforts by his war captain, Abner, as well as by David and Jonathan. The record says little about his administrative efforts or the details of the Israelite tribal alliances. Later we learn that the tribe of Judah supports David in opposition to Saul and his progeny, whose support seems to come more from the northern tribes, but few details are given.

Rejection

Samuel appears again and gives Saul another chance. He must make holy war against the people known as the Amalekites. To conduct the war acceptable to God, he must slay every last one of these people, including women and children, as well as livestock. His troops must also refrain from taking plunder of any kind.

Saul carries out a widespread assault against the Amalekites, killing all of them except their king, Agag. His troops, moreover, keep some of the best cattle alive. Saul erects a victory monument at Mt. Carmel and returns to Gilgal. Samuel, however, does not share his sense of joy. He angrily accuses the king of disobedience. The bewildered Saul protests, saying:

- I did obey the Lord. I went on the mission the Lord assigned me. I completely destroyed the Amalekites and brought back Agag their king. The soldiers took sheep and cattle from the plunder, the best of what was devoted to God, in order to sacrifice them to the Lord your God at Gilgal.

Samuel rejects this explanation as an excuse for disobedience. Saul then admits his sin and begs for forgiveness, pleading for Samuel to return with him "so that I might worship God." Samuel, however, declares that God has rejected Saul as king. He turns away, and Saul desperately grabs his garment, which rips. Samuel interprets this as a prophetic act, confirming that God has torn the kingdom from Saul. Samuel makes one concession and allows Saul to worship God with him. He then commands that Agag should be brought forth. He promptly "hews Agag in pieces" and leaves the scene, never to see Saul again in this life. (1 Sam. 15:35)

Saul and David

First encounter (two versions)

As David arrives on the scene, Saul is cast firmly in the role of antagonist. He becomes the dark central figure in a tragedy of Shakespearian proportions.

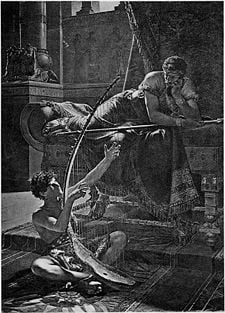

The text tells us that God's spirit has left Saul, and an "evil spirit from God" has obsessed him. (1 Sam. 16:14) Saul requests soothing music, and a servant recommends David the son of Jesse, who is renowned as a skillful harpist and warrior. David is appointed as Saul's armor bearer, playing the harp as needed to calm Saul's moods. Previously, we have been informed that Samuel has gone to Bethlehem and secretly anointed the young David to be Israel's king.

The story of David and Goliath intervenes at this point, clearly from a different source than the story above. Here, (1 Samuel 17:1-18:5) the Philistines return with an army to attack Israel, and Jesse sends David not as a harper to the king, but simply to carry food to his older brothers, who serve in the army. David learns that the giant Goliath has challenged Israel to send its champion to fight him. David volunteers for the task. Saul, who in this story has not met David previously, appoints the lad as his champion. David defeats Goliath and becomes the king's favorite. Jonathan, a kindred spirit to David, makes a pact with him, giving him his own clothing and weapons. Saul dispatches David on various military errands, and he wins renown. The story takes an ominous turn, however, as Israelite women take up the chant: "Saul has slain his thousands and David his tens of thousands." Saul now begins to see David as a possible threat to the throne.

Saul Turns against David

The text gives us an insight into Saul's spiritual character at this point as it describes him as "prophesying in his house" (1 Sam 18:10). Earlier it has described him as engaging in ecstatic prophesy with the bands of roving prophet-musicians associated with Samuel (1 Sam. 10:5). One might picture David and Saul engaging in this type intense spiritual-musical activity together, rather than David softly strumming while a depressed Saul lies next to him. This other-worldly tendency in Saul also apparently made him vulnerable to spiritual obsession. Thus while Saul was prophesying, the evil spirit from God "came forcefully upon him" and inspired him to attempt to murder David. David twice eludes the king's attacks, and Saul then sends David away, fearing the Lord's presence with him.

Ever caught in what modern readers would recognize as the throes of bi-polarism, Saul next decides to give David the hand of his daughter. First he offers David his eldest, Merab, and then Michal, the younger, who has fallen in love with David. David pleads that he is too poor to marry a king's daughter, but Saul insists, telling David that the bride-price will only be 100 foreskins from the Philistines. The narrator informs us that Saul actually intends that Philistines will prevail against David, but the champion returns with twice the required number. Having tendered this gory gift, David is married to Michal. Until this point, the text states that David continues to act as one of Saul's war captains, proving especially effective in several campaigns against the Philistines. The focus of the narrative, however, is to provide the details of several further plots by Saul against David.

Jonathan dissuades Saul from a plan to kill David and informs David of the plot. David (quite foolishly if the order of the story is correct) once again plays the harp for Saul, and Saul again tries to murder him. Saul then tries to have David killed during the night, but Michal helps him escape and tricks his pursuers by disguising a household idol to look like David in bed. David flees to Samuel.

Saul pursues David, but whatever evil influence controls him is no match for for the spiritual power of Samuel. The text here contracts (Should this be "contradicts"?) its earlier declaration that Samuel and Saul never met again:

- The Spirit of God came even upon him, and he walked along prophesying until he came to Naioth. He stripped off his robes and also prophesied in Samuel's presence. He lay that way all that day and night. (1 Sam. 19:23-24)

Leaving Samuel's protection, David goes to Jonathan, who agrees to act as David's intelligence agent in Saul's house. Saul sees through this and castigates Jonathan for disloyalty. It becomes clear that Saul wants David dead. Jonathan tells David of Saul's intent, and David again flees. Saul later causes Michal to marry another man in place of David.

Saul Pursues David

Saul now treats David as both a rival and a fugitive traitor. An Edomite named Doeg tells Saul that David had been hiding in a place named Nob, and that the priest there, Ahimelech, had helped David by giving material aid and consulting God for him. Saul summons Ahimelech and castigates him for his assistance to David, then orders henchmen to kill Ahimelech and the other priests of Nob. None of Saul's henchmen is willing to do this, so Doeg offers to do it instead, killing 85 priests. Doeg also slaughters every man, woman, and child still in Nob except Ahimilech's son Abiathar, who makes good his escape and informs David of events.

David amasses about 400 disaffected men together as a group of outlaws. With these men David attacks the Philistines at Keilah and evicts them from the city. Hearing the news, Saul leads his army there, intending to besiege the city. David learns of Saul's plan and through divination he knows that the citizens of Keilah will betray him to Saul. He flees to Ziph, where Saul again pursues him. The Bible retains two versions of the humorous story of Saul and David at Ziph, both involving David as a clever trickster who is in a position to slay Saul, but refrains due to his belief that to slay "the Lord's anointed" would be a sin.

Tiring of playing cat-and-mouse with Saul, David flees to the Philistine city of Gath, the birthplace of Goliath, where he offers himself as a mercenary general to King Achish, Israel's adversary. Seeing that his rival has gone over the enemy and seems no longer to seek the throne of Israel, Saul breaks off pursuit.

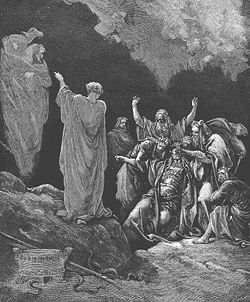

Battle of Mt. Gilboa

The Philistines now prepare to attack Israel, and Saul leads out his army to face them at Gilboa. Seeking in vain for God's advice through prophets, dreams, and divination, Saul searches for a medium through whom he can consult with the departed soul of Samuel. In so doing, Saul breaks his own law against such activity. At the village of Endor, he finds a woman who agrees to conjure the spirit of the famous judge. Samuel's ghost only confirms Saul's doom — that he would lose the battle, that Jonathan would be killed, and that Saul would soon join Samuel in Sheol.

Broken in spirit, Saul returns to the face the enemy, and the Israelites are soundly defeated. Three of Saul's sons — Jonathan, Abinadab and Malki-Shua — are slain. Saul himself suffers a critical arrow wound. To escape the ignominy of capture, Saul asks his armor bearer to kill him, but commits suicide by falling on his sword when the armor bearer refuses (1 Sam. 31 5).

In an alternative version of the story (2 Sam. 1), a young Amalekite presents Saul's crown to David — here the Amalekites have not been wiped out after all — and claims to have finished off Saul at his request. The body of Saul, with those of his sons, is publicly displayed by the Philistines on the wall of Beth-shan, while his armor is hung up in the the temple of the goddess Ashtaroth/Astarte. However, loyal inhabitants of Jabesh Gilead remembering Saul as their savior, rescue the bodies, where they are honorably burned and buried (were these actions both done? Please double check. I thought they were only buried.).

Saul's legacy

2 Samuel 1 preserves a hymn praising Saul, which it characterizes as having been composed by David upon hearing of Saul's death. It reads, in part:

- Your glory, O Israel, lies slain on your heights.

- How the mighty have fallen!

- Tell it not in Gath, proclaim it not in the streets of Ashkelon,

- Lest the daughters of the Philistines be glad,

- Lest the daughters of the uncircumcised rejoice.

- O mountains of Gilboa,

- May you have neither dew nor rain,

- Nor fields that yield offerings of grain .

- For there the shield of the mighty was defiled,

- the shield of Saul—-no longer rubbed with oil.

- From the blood of the slain,

- from the flesh of the mighty,

- the bow of Jonathan did not turn back,

- the sword of Saul did not return unsatisfied. (2 Sam. 1:20-22)

The sources are rather confused regarding Saul's descendants. According to 1 Samuel, Saul had three sons (Jonathan, Ishvi and Malki-Shua) — and two daughters (Merab and Michal). Saul's primary wife is named as Ahinoam, daughter of Ahimaaz. 1 Chronicales 8:33 says that Saul's sons were named Jonathan, Malki-Shua, Abinadab and Esh-Baal. 2 Samuel calls the latter son Esh-Baal (man of Baal) Ish-Bosheth (Man of Shame). In addition, 2 Samuel 21:8 refers to "Armoni and Mephibosheth" as "the two sons of Aiah's daughter Rizpah, whom she had borne to Saul." Earlier references to Mephibosheth in 2 Samuel, however, speak of him as Jonathan's son, not Saul's.

In any case Ish-Bosheth/Esh-Baal apparently reigned as king of Israel from Saul's stronghold of Gibeah after Saul's death. David, meanwhile, reigned in Hebron as the king of single tribe of Judah.

There followed a long and bitter civil war between Judah (supporting David) and the northern tribes (supporting Ish-Bosheth). Eventually, Abner, Saul's cousin and former army commander and advisor, broke with Ish-Bosheth and went over to David's side, bringing with him key elements of the northern alliance, including David's first wife Michal. The war finally ended when Ish-Bosheth was assassinated by two of his own men.

With Ish-Bosheth out of the picture, the leaders of the northern tribes came to David and declared him king by popular assent (2 Sam. 5). David held Saul's one remaining grandson, Mephibosheth, under gentle house arrest in Jerusalem. Several northern factions formerly loyal to Saul held out against David and mounted rebellions against his rule.

Critical View

An objective assessment of Saul's contribution to the history of Israel necessitates an attempt to liberate the "historical Saul" from the pro-Davidic narrative that constitutes our only source for his reign. One has only to recognize that the writers allow Saul's adversary, David, to deliver his eulogy to understand this.

In what sense is it even accurate to think of Saul as a "king" other than the fact that he was reportedly anointed as such? He was reportedly able to muster and lead a very effective army, but other than the degree of his military success what did he do as a king? Did he truly unite the Israelite tribes into a national federation with a centralized administration?

The answers to such questions are not easy, since so little such information is given in the narrative, and some of the sources seem to come from a later period in which the monarchic institutions were well established and editors may have projected the realities of their own day back into the history of Israel under Saul.

Archaelogical findings, such as those discussed by Israel Finkelstein in "The Bible Unearthed," lead many scholars to conclude that the population of Israel in the time of Saul was still very small and incapable of supporting an administrative apparatus resembling that of the other monarchic societies that surrounded and sometimes infringed on the Israelite tribal lands. Indeed, little in the narrative itself speaks of Saul as a governing monarch as opposed to a military leader. Rather than seeing him as failed king, we may do more justice to his memory to think of him as an effective fighter for Israel's independence who helped lay the foundation for a monarchy that was yet to emerge.

Regarding the text itself, according to critical scholars, the story of Saul's life is essentially a splicing together of two or more originally distinct sources.

- A monarchial source begins with the divinely appointed birth of Samuel (many scholars think it originally referred to Saul, see above). It then describes Saul's battle against the Ammonites, his being chosen by the people to be a king, and his bravely leading them against the Philistines.

- A republican source includes such themes as Samuel's opposition to the institution of the monarchy, Saul's usurpation of the priestly office, Saul's failure to follow God's instructions in the holy war against the Amalekites, David's sparing Saul's life as "the Lord's anointed," and Saul's resorting to to consult the "witch" of Endor.

- Scholars also speculate that a sanctuaries source may exist, related to the history of various holy places such as Gilgal, Carmel, Bethel, etc. Finally, the hand of a "redactor" is seen, a later editor who has inserted various summaries and judgments in accordance with the viewpoint of his particular period.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This article incorporates text from the 1901-1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

- Finkelstein, Israel. 2002. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0684869136

- Finkelstein, Israel, and David Silberman. David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. New York: Free Press (Simon and Schuster), 2006. ISBN 0743243625

- Kirsch, Jonathan. 2000. King David: the real life of the man who ruled Israel. Hendersonville, TN: Ballantine. ISBN 0345432754.

- Pinsky, Robert. The Life of David. Schocken, 2005. ISBN 0805242031

- Sanford, John A. King Saul, the Tragic Hero: A Study in Individuation. Paulist Press, 1985. ISBN: 0809126583

- Wellhausen, Der Text der Bücher Samuelis (Any other info?)

- K. Budde, Die Bücher Richter und Samuel, 1890, pp. 167-276;

- S. R. Driver, Notes on the Hebrew Text of the Books of Samuel, 1890;

- T. K. Cheyne, Aids to the Devout Study of Criticism, 1892, pp. 1-126;

- H. P. Smith, Old Testament History, 1903, ch. vii.;

- Cheyne and Black, Encyclopedia Biblica (Any other info?)

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.