Difference between revisions of "Necker cube" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Category:Psychology]] | [[Category:Psychology]] | ||

| − | + | The '''Necker cube''' is an [[optical illusion]] that consists of a two dimensional representation of a three dimensional wire frame cube. The Necker cube is similar to the [[impossible cube]]. | |

| − | |||

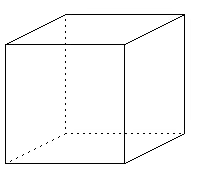

[[Image:Necker cube.svg|thumb|The Necker cube: a wire frame cube with no depth cues.]] | [[Image:Necker cube.svg|thumb|The Necker cube: a wire frame cube with no depth cues.]] | ||

| + | ==Discovery== | ||

| + | The Necker cube was first described in 1832 by [[Switzerland|Swiss]] [[crystallographer]] [[Louis Albert Necker]], who observed that ambiguous cubic shapes could spontaneously switch perspective. Necker first described his findings in a letter to Sir David Brewster. Although a cube is generally used to illustrate the illusion, Necker first used a [[rhomboid]].<ref>Gregory, Richard. [http://www.richardgregory.org/papers/brainmodels/illusions-and-brain-models_p1.htm "Perceptual illusions and brain models"] Proc. Royal Society B 171 179-296. Retrieved October 22, 2007</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==Description== | |

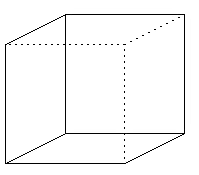

| − | + | [[Image:Cube1.PNG|thumb|left|One possible interpretation of the Necker cube, often claimed to be the most common interpretation]][[Image:Cube2.PNG|thumb|left|The other interpretation]] | |

| − | + | The Necker cube is an ambiguous line drawing of a wire-frame cube. Drawn in isometric perspective (parallel edges of the cube are drawn as parallel lines), there are no cues to determine whether one line crosses in front of or behind another. This creates an ambiguous situation where there are two possible orientations of the three dimensional cube. When a person looks at a drawing of the Necker cube, it often appears to flip back and forth between the two valid interpretations (an effect often called [[multistable perception]]). | |

| − | The Necker cube is an ambiguous line drawing | ||

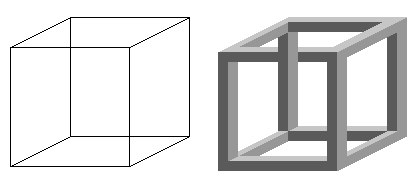

| − | [[Image:Necker cube and impossible cube.PNG|frame|Necker cube on the left, [[impossible cube]] on the right.]] | + | [[Image:Necker cube and impossible cube.PNG|frame|Necker cube on the left, [[impossible cube]] on the right.]] |

| + | ==Explanation== | ||

| + | Because of the ambiguity of the line drawing, the brain chooses an interpretation of the ambiguous parts that makes the whole figure consistent. It is rare that one will see an inconsistent interpretation of the cube; the brain picks one of the two interpretations that would be possible in the three dimensional world. (A version of the Necker cube where the edges cross in inconsistent ways is found in the [[impossible cube]].) | ||

| − | + | When viewing the Necker cube, people most often see the lower-left face as being in front. This is possibly because people view objects from above more often than from below. When given a choice, the brain chooses the interpretation that most closely matches everyday experience. It is interesting to note that [[Sidney Bradford]], [[blindness|blind]] from a very early age but regaining his sight following an operation at age 52, did not perceive the ambiguity that normal-sighted observers do. Additionally, Bradford was unable to perceive depth in the illusion, which supports the idea that the brain interprets visual images based on past experiences.<ref>Gregory, Richard and J. G. Wallace. [http://www.richardgregory.org/papers/recovery_blind/3-observations_p2.htm "Recovery from Early Blindness"] 1963. Experimental Psychology Society Monograph No. 2. Retrieved October 22, 2007</ref> | |

| − | + | There is evidence that by focusing on different parts of the figure one can force a more stable perception of the cube. At diagonally opposite corners of the rectangle in the center of the figure are two "y-junctions". By focusing on the "y-junction" in the upper right corner of the central rectangle, the lower left face will appear to be in front. By focusing on the lower junction, the upper right face will appear to be in front (Einhauser, et al., 2004). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | There is evidence that by focusing on different parts of the figure one can force a more stable perception of the cube. | ||

| − | The Necker cube has shed light on the human visual system. The phenomenon has served as evidence of the [[human brain]] being a [[neural network]] with two distinct equally possible interchangeable stable states.<ref>David | + | The Necker cube has shed light on the human visual system. The phenomenon has served as evidence of the [[human brain]] being a [[neural network]] with two distinct equally possible interchangeable stable states.<ref>Marr, David. ''Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information''. 1983. W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0716715678</ref> |

| − | == | + | ==Applications== |

| − | The Necker cube is used | + | The Necker cube, like many perceptual and visual illusions, is used to further the study of how the brain and visual system perceive and interpret information. |

| − | + | Additionally, the Necker cube is often used as an example in [[epistemology]] (the study of knowledge). The Necker cube helps to provide a counter-attack against [[naïve realism]], also known as ''direct'' or ''common-sense'' realism, which states that the way we perceive the world is the way the world actually is. The Necker cube seems to disprove this claim because we see one or the other of two cubes, but really, there is no cube there at all: only a [[two-dimensional]] drawing of twelve lines. We see something which is not really there, thus (allegedly) disproving naïve realism. This criticism of naïve realism supports [[representative realism]]. | |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 35: | Line 33: | ||

* [http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/links/doi/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03722.x/abs/ Einhäuser, Wolfgang, Martin, Kevan A. C. & König, Peter (2004) Are switches in perception of the Necker cube related to eye position?. ''European Journal of Neuroscience 20 (10)'', 2811-2818.] | * [http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/links/doi/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03722.x/abs/ Einhäuser, Wolfgang, Martin, Kevan A. C. & König, Peter (2004) Are switches in perception of the Necker cube related to eye position?. ''European Journal of Neuroscience 20 (10)'', 2811-2818.] | ||

| − | + | *Frith, Chris. ''Making up the Mind: How the Brain Creates Our Mental World'' April 2007. Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 1405160225 | |

| Line 41: | Line 39: | ||

* [http://www.cs.ubc.ca/nest/imager/contributions/flinn/Illusions/NC/nc.html history of the cube and a Java applet] | * [http://www.cs.ubc.ca/nest/imager/contributions/flinn/Illusions/NC/nc.html history of the cube and a Java applet] | ||

| − | * [http://www.cs.cf.ac.uk/Dave/JAVA/boltzman/Necker.html | + | * [http://www.cs.cf.ac.uk/Dave/JAVA/boltzman/Necker.html modeling human perception of the cube] |

*[http://enane.de/llpol.htm Explanation of the Necker cube and other gestalt phenomena] | *[http://enane.de/llpol.htm Explanation of the Necker cube and other gestalt phenomena] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credits|Necker_cube|157511847|}} | {{Credits|Necker_cube|157511847|}} | ||

Revision as of 17:37, 22 October 2007

The Necker cube is an optical illusion that consists of a two dimensional representation of a three dimensional wire frame cube. The Necker cube is similar to the impossible cube.

Discovery

The Necker cube was first described in 1832 by Swiss crystallographer Louis Albert Necker, who observed that ambiguous cubic shapes could spontaneously switch perspective. Necker first described his findings in a letter to Sir David Brewster. Although a cube is generally used to illustrate the illusion, Necker first used a rhomboid.[1]

Description

The Necker cube is an ambiguous line drawing of a wire-frame cube. Drawn in isometric perspective (parallel edges of the cube are drawn as parallel lines), there are no cues to determine whether one line crosses in front of or behind another. This creates an ambiguous situation where there are two possible orientations of the three dimensional cube. When a person looks at a drawing of the Necker cube, it often appears to flip back and forth between the two valid interpretations (an effect often called multistable perception).

Explanation

Because of the ambiguity of the line drawing, the brain chooses an interpretation of the ambiguous parts that makes the whole figure consistent. It is rare that one will see an inconsistent interpretation of the cube; the brain picks one of the two interpretations that would be possible in the three dimensional world. (A version of the Necker cube where the edges cross in inconsistent ways is found in the impossible cube.)

When viewing the Necker cube, people most often see the lower-left face as being in front. This is possibly because people view objects from above more often than from below. When given a choice, the brain chooses the interpretation that most closely matches everyday experience. It is interesting to note that Sidney Bradford, blind from a very early age but regaining his sight following an operation at age 52, did not perceive the ambiguity that normal-sighted observers do. Additionally, Bradford was unable to perceive depth in the illusion, which supports the idea that the brain interprets visual images based on past experiences.[2]

There is evidence that by focusing on different parts of the figure one can force a more stable perception of the cube. At diagonally opposite corners of the rectangle in the center of the figure are two "y-junctions". By focusing on the "y-junction" in the upper right corner of the central rectangle, the lower left face will appear to be in front. By focusing on the lower junction, the upper right face will appear to be in front (Einhauser, et al., 2004).

The Necker cube has shed light on the human visual system. The phenomenon has served as evidence of the human brain being a neural network with two distinct equally possible interchangeable stable states.[3]

Applications

The Necker cube, like many perceptual and visual illusions, is used to further the study of how the brain and visual system perceive and interpret information.

Additionally, the Necker cube is often used as an example in epistemology (the study of knowledge). The Necker cube helps to provide a counter-attack against naïve realism, also known as direct or common-sense realism, which states that the way we perceive the world is the way the world actually is. The Necker cube seems to disprove this claim because we see one or the other of two cubes, but really, there is no cube there at all: only a two-dimensional drawing of twelve lines. We see something which is not really there, thus (allegedly) disproving naïve realism. This criticism of naïve realism supports representative realism.

Notes

- ↑ Gregory, Richard. "Perceptual illusions and brain models" Proc. Royal Society B 171 179-296. Retrieved October 22, 2007

- ↑ Gregory, Richard and J. G. Wallace. "Recovery from Early Blindness" 1963. Experimental Psychology Society Monograph No. 2. Retrieved October 22, 2007

- ↑ Marr, David. Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. 1983. W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0716715678

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Einhäuser, Wolfgang, Martin, Kevan A. C. & König, Peter (2004) Are switches in perception of the Necker cube related to eye position?. European Journal of Neuroscience 20 (10), 2811-2818.

- Frith, Chris. Making up the Mind: How the Brain Creates Our Mental World April 2007. Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 1405160225

External links

- history of the cube and a Java applet

- modeling human perception of the cube

- Explanation of the Necker cube and other gestalt phenomena

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.