Difference between revisions of "Muller-Lyer illusion" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Category:Psychology]] | [[Category:Psychology]] | ||

| + | The '''Müller-Lyer illusion''' is an [[optical illusion]] consisting of a set of lines that end in arrowheads. The orientation of the arrowheads affects one's ability to accurately perceive the length of the lines. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Discovery== | ||

| + | The Müller-Lyer illusion is named for [[Franz Carl Müller-Lyer]], a German psychiatrist and sociologist. Müller-Lyer published fifteen versions of the illusion in an 1889 issue of the German journal ''Zeitschrift für Psychologie''.<ref>[http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O87-MllerLyerillusion.html "Müller-Lyer Illusion"] 2001. Oxford University Press. Retrieved October 17, 2007.</ref> | ||

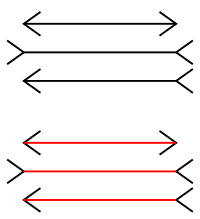

[[Image:Müller-Lyer illusion.svg|thumb|the Müller-Lyer optical illusion with arrows. Both set of arrows are exactly the same, the bottom one shows how the arrows are of the exact same length.|200px]] | [[Image:Müller-Lyer illusion.svg|thumb|the Müller-Lyer optical illusion with arrows. Both set of arrows are exactly the same, the bottom one shows how the arrows are of the exact same length.|200px]] | ||

| + | ==Description== | ||

| + | The most well known version of the Müller-Lyer illusion consists of two parallel lines, one of which ends in inward pointing arrows, the other which ends with outward pointing arrows. When observing the two lines, the one with the inward pointing arrows appears to be significantly longer than the other. In other versions, one of each type of arrow is put at each end of a single line. The viewer attempts to identify the middle point of the line, only to find that he/she is consistently off to one side. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Explanation== | ||

| + | It is unclear exactly what causes the Müller-Lyer illusion to take place, but there are a number of theories. One of the most popular is the perspective explanation. | ||

| − | The | + | In the three-dimensional world, we often use angles to judge depth and distance. Living in a "carpentered world", we have grown accustomed to seeing corners everywhere. The brain is used to viewing such angles and interpreting them as far and near corners, and also uses this information to make size judgments. When looking at the Müller-Lyer arrows, the brain interprets them as far and near corners, and overrides the retinal information that says both lines are the same length. This explanation is supported by studies comparing the response to the Müller-Lyer illusion by American children and both rural and urban Zambian children. American children were susceptible to the illusion, and the urban Zambian children were more susceptible than the rural Zambian children. Since the rural Zambian children were much less exposed to rectangular structures, this would seem to support the perspective (or "carpentered world") theory. Interestingly enough, the illusion also persists when the arrows are replaced by circles, which have nothing to do with perspective or corners, and would seem to negate the perspective theory.<ref>[http://www.everything2.com/index.pl?node_id=773882 "Muller-Lyer Illusion"] June 2002. Retrieved October 17, 2007.</ref> |

| − | + | Another popular theory has been the ''eye movement theory'', which states that we perceive one line as longer because it takes more eye movements to view a line with inward pointing arrows than it does a line with outward pointing arrows. This explanation is largely dismissed, as the illusion persists even when there is no eye movement at all. | |

| − | + | Also popular has been the ''assimilation theory'', which states that we see one line as longer because the visual system is unable to separate the figure into parts. As a whole figure, the line with inward pointing arrows is indeed longer. This theory is also generally dismissed.<ref>Howe, Catherine Q. and Dale Purves. [http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/102/4/1234 "The Müller-Lyer illusion explained by the statistics of image–source relationships"] December 2004. The Center for Cognitive Neuroscience at Duke University. Retrieved October 17, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Applications== | |

| + | Like most visual and perceptual illusions, the Müller-Lyer illusion helps neuroscientists study the way the brain and visual system perceive and interpret images. | ||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | <references/> | ||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | *Godfrey-Smith, Peter. ''Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science'' August 2003. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226300633 | ||

| + | *Merleau-Ponty. ''Phenomenology of Perception'' May 2002. Routledge. ISBN 0415278414 | ||

| + | *Thomas, Ed. Gilovich. ''Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment'' 2002. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521796792 | ||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 19:26, 17 October 2007

The Müller-Lyer illusion is an optical illusion consisting of a set of lines that end in arrowheads. The orientation of the arrowheads affects one's ability to accurately perceive the length of the lines.

Discovery

The Müller-Lyer illusion is named for Franz Carl Müller-Lyer, a German psychiatrist and sociologist. Müller-Lyer published fifteen versions of the illusion in an 1889 issue of the German journal Zeitschrift für Psychologie.[1]

Description

The most well known version of the Müller-Lyer illusion consists of two parallel lines, one of which ends in inward pointing arrows, the other which ends with outward pointing arrows. When observing the two lines, the one with the inward pointing arrows appears to be significantly longer than the other. In other versions, one of each type of arrow is put at each end of a single line. The viewer attempts to identify the middle point of the line, only to find that he/she is consistently off to one side.

Explanation

It is unclear exactly what causes the Müller-Lyer illusion to take place, but there are a number of theories. One of the most popular is the perspective explanation.

In the three-dimensional world, we often use angles to judge depth and distance. Living in a "carpentered world", we have grown accustomed to seeing corners everywhere. The brain is used to viewing such angles and interpreting them as far and near corners, and also uses this information to make size judgments. When looking at the Müller-Lyer arrows, the brain interprets them as far and near corners, and overrides the retinal information that says both lines are the same length. This explanation is supported by studies comparing the response to the Müller-Lyer illusion by American children and both rural and urban Zambian children. American children were susceptible to the illusion, and the urban Zambian children were more susceptible than the rural Zambian children. Since the rural Zambian children were much less exposed to rectangular structures, this would seem to support the perspective (or "carpentered world") theory. Interestingly enough, the illusion also persists when the arrows are replaced by circles, which have nothing to do with perspective or corners, and would seem to negate the perspective theory.[2]

Another popular theory has been the eye movement theory, which states that we perceive one line as longer because it takes more eye movements to view a line with inward pointing arrows than it does a line with outward pointing arrows. This explanation is largely dismissed, as the illusion persists even when there is no eye movement at all.

Also popular has been the assimilation theory, which states that we see one line as longer because the visual system is unable to separate the figure into parts. As a whole figure, the line with inward pointing arrows is indeed longer. This theory is also generally dismissed.[3]

Applications

Like most visual and perceptual illusions, the Müller-Lyer illusion helps neuroscientists study the way the brain and visual system perceive and interpret images.

Notes

- ↑ "Müller-Lyer Illusion" 2001. Oxford University Press. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ↑ "Muller-Lyer Illusion" June 2002. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ↑ Howe, Catherine Q. and Dale Purves. "The Müller-Lyer illusion explained by the statistics of image–source relationships" December 2004. The Center for Cognitive Neuroscience at Duke University. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Godfrey-Smith, Peter. Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science August 2003. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226300633

- Merleau-Ponty. Phenomenology of Perception May 2002. Routledge. ISBN 0415278414

- Thomas, Ed. Gilovich. Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment 2002. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521796792

External links

- Müller-Lyer Illusion

- The Müller-Lyer illusion explained by the statistics of image–source relationships

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.