John Singleton Copley

| John Singleton Copley | |

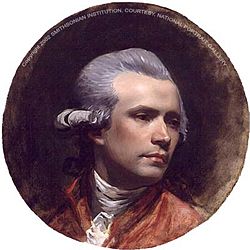

Portrait of Copley by Gilbert Stuart | |

| Birth name | John Singleton Copley |

| Born | 1738 Boston, Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Died | September 9 1815 London, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | American |

| Field | Portraiture |

John Singleton Copley (1738[1] - 1815) was an American painter, born presumably in Boston, Massachusetts to Richard and Mary Singleton Copley. He is famous for his portraits of important figures in colonial New England, depicting in particular middle-class subjects. His paintings were innovative in their tendency to depict artifacts relating to these individuals' lives.

Biography

Early life

Except for a family tradition that speaks of his precocity in drawing, nothing is known of Copley's schooling or of the other activities of his boyhood. His letters, the earliest of which is dated September 30, 1762, reveal a fairly well-educated man. He may have been taught various subjects, it is reasonably conjectured, by his future step-father who painted portraits, cut engravings, and conducted a school out of their home. In such a household, young Copley may have learned to use the paintbrush and the engraver's tools.[2]

Lord Lyndhurst, his son, wrote that "he (Copley) was entirely self taught, and never saw a decent picture, with the exception of his own, until he was nearly thirty years of age."[3] Copley himself complained, in a letter to Benjamin West, written November 12, 1766: "In this Country as You rightly observe there is no examples of Art, except what is to [be] met with in a few prints indifferently exicuted, from which it is not possable to learn much".[4] Variants of this thesis are found almost everywhere in his earlier letters. They suggest that while Copley was industrious and an able executant he was physically unadventurous and temperamentally inclined toward brooding and self-pity. He could have seen at least a few good paintings and many good prints in the Boston of his youth. The excellence of his own portraits was not accidental or miraculous; it had an academic foundation. A book of Copley's studies of the figure, now at the British Museum, proves that before he was twenty, whether with or without help from a teacher, he was making anatomical drawings with much care and precision. It is likely that through the fortunate associations of a home and workshop in a town which had many craftsmen he had already learned his trade at an age when the average art student of a later era was only beginning to draw.

Rising reputation

Besides painting portraits in oil, Copley was a pioneer American pastellist. By the 1760's, he acquired pastels upon request of Swiss painter Jean-Étienne Liotard, and begun to demonstrate his genius for rendering surface textures and capturing emotional immediacy.[5]

Copley's fame was established in England by the exhibition, in 1766,[6] of The Boy with the Squirrel, which depicted his half-brother, Henry Pelham, seated at a table and playing with a pet squirrel. This picture, which made the young Boston painter a Fellow of the Society of Artists of Great Britain, by vote of September 3, 1766, had been painted the preceding year. Copley's letter of September 3, 1765, to Capt. R. G. Bruce, of the John and Sukey, reveals that it was taken to England as a personal favor in the luggage of Roger Hale, surveyor of the port of London. An anecdote relates that the painting, unaccompanied by name or letter of instructions, was delivered to Benjamin West (whom Mrs. Amory describes as then "a member of the Royal Academy," though the Academy was not yet in existence). West is said to have "exclaimed with a warmth and enthusiasm of which those who knew him best could scarcely believe him capable, 'What delicious coloring worthy of Titian himself!'" The American squirrel, it is said, disclosed the colonial origin of the picture to the Pennsylvania-born Quaker artist. A letter from Copley was subsequently delivered to him. West got the canvas into the Exhibition of the year and wrote, on August 4, 1766, a letter to Copley in which he referred to Sir Joshua Reynolds's interest in the work and advised the artist to follow his example by making "a viset to Europe for this porpase (of self-improvement) for three or four years."

West's subsequent letters were considerably responsible for making Copley discontented with his situation and prospects in a colonial town. Copley in his letters to West of October 13 and November 12, 1766 gleefully accepted the invitation to send other pictures to the Exhibition and mournfully referred to himself as "peculiarly unlucky in Liveing in a place into which there has not been one portrait brought that is worthy to be call'd a Picture within my memory." In a later letter to West, of June 17, 1768, he displayed a cautious person's reasons for not rashly giving up the good living which his art gave him. He wrote: "I should be glad to go to Europe, but cannot think of it without a very good prospect of doing as well there as I can here. You are sensable that 300 Guineas a Year, which is my present income, is a pretty living in America. . . . And what ever my ambition may be to excel in our noble Art, I cannot think of doing it at the expence of not only my own happyness, but that of a tender Mother and a Young Brother whose dependance is intirely upon me".[7] West replied on September 20, 1768, saying that he had talked over Copley's prospects with other artists of London "and find that by their Candid approbation you have nothing to Hazard in Comeing to this Place."

The Move to London

Leaving his family to the care of his half brother, Henry Pelham, Copley sailed from Boston to London in June 1774. After a tour of the European continent and artwork, he and his family moved to London 1775, where they resided for the rest of their lives.[8]

As an English painter Copley began in 1775 a career promising at the outset and destined from personal and political causes to end in gloom and adversity. His technique was so well established, his habits of industry so well confirmed, and the reputation that had preceded him from America was so extraordinary, that he could hardly fail to make a place for himself among British artists. He himself, however, "often said, after his arrival in England, that he could not surpass some of his early works".[9] The deterioration of his talent was gradual, however, so some of the "English Copleys" are superb paintings.

Following a fashion set by West and others, Copley began to paint historical pieces as well as portraits. His first foray into this genre was A Youth Rescued from a Shark, its subject based on an incident related to the artist by Brook Watson, who had been attacked by a shark while swimming in Havana harbour as a 14-year-old boy.Engravings from this work achieved an enduring popularity.

However, the artist's fame as a historical painter was made by The Death of Lord Chatham, which brought him denunciation from Sir William Chambers, president of the Royal Academy, who objected to its being exhibited privately in advance of the Academy's exhibition. In an open letter Chambers accused Copley of purveying his picture like a "raree-show" and of aiming for "either the sale of prints or the raffle of the picture." To this censure, obviously unfair to one newly-arrived in London and uninformed as to the professional ethics of exhibiting, Copley one morning wrote a caustic reply, and in the evening wisely threw it into the fire. Engravings from the Chatham picture later sold well in England and America.

Copley's adventures in historical painting were the more successful because of his painstaking efforts to obtain good likenesses of personages and correct accessories of their periods. He traveled much in England to make studies of old portraits and actual localities. At intervals came from his studio such pieces as The Red Cross Knight, Abraham Offering up Isaac, Hagar and Ishmael in the Wilderness, The Death of Major Pierson, The Arrest of Five Members of the Commons by Charles the First, The Siege of Gibraltar, The Surrender of Admiral DeWindt to Lord Camperdown, The Offer of the Crown to Lady Jane Grey by the Dukes of Northumberland and Suffolk, The Resurrection, and others. He continued to paint portraits, among them those of several members of the royal family and numerous British and American celebrities. Between 1776 and 1815 he sent forty-three paintings to exhibitions of the Royal Academy, of which he was elected an associate member in the former year. His election to full membership occurred in 1783.[10]

He would have liked to return to America but his professional routine prevented this. He was politically more liberal than were his relatives. He painted the Stars and Stripes over a ship in the background of Elkanah Watson's portrait on December 5, 1782, after listening to George III's speech formally acknowledging American independence. Copley's contacts with New England people continued to be many. He painted portraits of John Adams, John Quincy Adams, and other Bostonians who visited England. His daughter Elizabeth was married in August 1800 to Gardiner Greene of Boston, a wealthy gentleman whose descendants preserved much of the correspondence of the Copley family.

Decline

In his last fifteen years, though painting persistently, Copley experienced much depression and disappointment. The Napoleonic Wars brought hard times. The household at 25 George St. was expensive to maintain. The education of a talented son was costly. It grieved the father that after the young barrister began to earn his way it became necessary to accept his help in supporting the home. Lord Campbell quotes the jurist as saying that "his father, having lived rather expensively, accumulated little for him."[11] Mrs. Amory makes out a case for Mrs. Copley's admirable management,[12] but it appears that a standard of living difficult to maintain in the changed circumstances made much borrowing inevitable. Copley was chagrined by the failure of his Equestrian Portrait of the Prince Regent to "bring a financial return." Cunningham says, "No customer made his appearance for Charles and the impeached members." Other canvases involving years of labor were unsold. Troubles with engravers were many, whether the fault was theirs or the painter's. Copley's letters to his son-in-law in Boston usually concerned loans made to him and frequently extended.

The aging artist's physical and mental health produced anxiety. In 1810 he had a bad fall which kept him from painting for a month.[13] He incessantly bewailed the loss of his Boston property. Mrs. Copley wrote on December 11, 1810: "Your father has been led to feel this affair [his unsuccessful litigation to recover the "farm"] more sensibly from the present state of things in this country where every difficulty of living is increasing and the advantages arising from his profession are decreasing".[14] In October 1811, Copley wrote to Greene in distress, craving an additional loan of £600. And on March 4, 1812 he wrote: "I am still pursuing my profession in the hope that, at a future time, a proper amount will be realized from my works, either to myself or family, but at this moment all pursuits which are not among the essentials of life are at a stand".[15] In August 1813, Mrs. Copley wrote that, although her husband was still painting, "he cannot apply himself as closely as he used to do." She reported in April 1814: "Your father enjoys his health but grows rather feeble, dislikes more and more to walk; but it is still pleasant for him to go on with his painting." In June 1815, the Copleys entertained as visitor John Quincy Adams, with whom they jubilantly discussed the new terms of peace between the United States and the United Kingdom. In the letter describing this visit the painter's infirmities are said to have been increased by "his cares and disappointments." A note of August 18, 1815, informed the Greenes that Copley while at dinner had had a paralytic stroke. He seemed at first to recover. Late in August his prognosis was favorable to his painting again. A second shock occurred, however, and he died on September 9, 1815. "He was perfectly resigned," wrote his daughter Mary, "and willing to die, and expressed his firm trust in God, through the merits of our Redeemer." He was buried in Highgate Cemetery in a tomb belonging to the Hutchinson family.

How deep into debt Copley had fallen in his latest years was hinted at in Mrs. Copley's letter of February 1, 1816, to Gardiner Greene in which she gave details of his assets and borrowings and predicted: "When the whole property is disposed of and applied toward the discharge of the debts a large deficiency must, it is feared, remain." The estate was settled by Copley's son, later Lord Lyndhurst, who maintained the establishment in George St., supported his mother down to her death in 1836, and kept the ownership of many of the artist's unsold pictures until March 5, 1864, when they were sold at auction in London. Several of the works then dispersed are now in American collections.

Legacy

Copley was the greatest and most influential painter in colonial America, producing about 350 works of art. With his startling likenesses of persons and things, he came to define a realist art tradition in America. His visual legacy extended throughout the nineteenth century in the American taste for the work of artists as diverse as Fitz Henry Lane and William Harnett. In Britain, while he continued to paint portraits for the élite, his great achievement was the development of contemporary history painting, which was a combination of reportage, idealism, and theatre. He was also one of the pioneers of the private exhibition, orchestrating shows and marketing prints of his own work to mass audiences that might otherwise attend exhibitions only at the Royal Academy, or who previously had not gone to exhibitions at all.[16]

Boston's Copley Square and Copley Plaza bear his name.

Major works

John Hancock (1765)

Samuel Adams (1772)

Paul Revere (1770)

The Return of Neptune (1754)

Notes

- ↑ Allan Cunningham gives the date of his birth as July 3, 1737 (The Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, 1830-33, V, 162), but the published Boston Records have no entry confirming this date. Copley himself wrote on September 12, 1766, to Peter Pelham, his step-brother, that he had had "resolution enough to live a bachelor to the age of twenty-eight" ("Letters and Papers of John Singleton Copley and Henry Pelham", p. 48, Mass. Hist. Soc. Colls., vol. LXXI (1914)). His daughter, Elizabeth Clarke Greene (in a letter quoted by William Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, vol. I, p. 119. Ed. F. W. Bayley and C. E. Goodspeed, 1918) spoke of her father as "born in 1738." Worthington C. Ford, editor of the Copley-Pelham correspondence, and Frank W. Bayley, a biographer, accept the evidence as indicating that the artist "was born in 1738, and not in 1737 as usually stated" ("Copley-Pelham Letters," p. 48).

- ↑ Whitmore, p. 29.

- ↑ Amory, p. 9.

- ↑ "Copley-Pelham Letters", p. 51.

- ↑ "Copley-Pelham Letters", p. 26.

- ↑ Not in 1760, as stated by Mrs. Amory, and not in 1774 as stated by Michael Bryan in Dictionary of Painters and Engravers (1898).

- ↑ "Copley-Pelham Letters", pp. 68-9.

- ↑ Amory, p. 99.

- ↑ Amory, p. 76.

- ↑ Cunningham, v. IV, p. 145.

- ↑ Lives of Lord Lyndhurst and Lord Brougham, 1869.

- ↑ Amory, p. 176.

- ↑ Amory, p. 300.

- ↑ Amory, p. 301.

- ↑ Amory, p. 304.

- ↑ DNB.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- "John Singleton Copley". Dictionary of American Biography. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928-1936.

- "Copley, John Singleton" in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

External links

- National Gallery of Art: John Singleton Copley

- National Gallery of Art: Watson and the Shark

- Find-A-Grave profile for John Singleton Copley

- Gallery of Copley's Paintings

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.