John Law (economist)

John Law (baptized April 21, 1671 - March 21, 1729) was a Scottish economist who believed that money was only a means of exchange that did not constitute wealth in itself, and that national wealth depended on trade.

John Law was also a "..reckless, and unbalanced, but most fascinating genius…" as Alfred Marshall (1923, p.41) called him, with "…the pleasant character mixture of swindler and prophet…." as Karl Marx (1894 p.441) added. An economist, gambler, banker, murderer, royal advisor, exile, rake and adventurer, the remarkable John Law is renowned for more than his unique economic theories.

His popular fame rests on two remarkable enterprises he conducted in Paris: the Banque Générale and the Mississippi Scheme. His economic fame rests on two major ideas: the scarcity theory of value and the real bills doctrine of money. He is said to be the father of finance, responsible for the adoption or use of paper money or bills in the world today.

Law was a gambler and a brilliant mental calculator, and was known to win card games by mentally calculating the odds. An expert in statistics, he was the originator of economic theories, including two major ideas: Water-Diamond paradox that evolved into Real bills doctrine and the, so called Law's System.

Biography

John Law was born into a family of bankers and goldsmiths from Fife; his father had purchased a landed estate at Cramond on the Firth of Forth and was known as Law of Lauriston. Law joined the family business aged fourteen and studied the banking business until his father died in 1688. Law subsequently neglected the firm in favour of more extravagant pursuits and travelled to London where he lost large sums of money in gambling. On 9 April 1694 John Law fought a duel with Edward Wilson. Wilson had challenged Law over the affections of Elizabeth Villiers. Wilson was killed and Law was tried and found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted to a fine, upon the ground that the offence only amounted to manslaughter. Wilson's brother appealed and had Law imprisoned but he managed to escape to the continent. Law urged the establishment of a national bank to create and increase instruments of credit, and the issue of paper money backed by land, gold, or silver. The first manifestation of Law's system came when he had returned to his homeland and contributed to the debates leading to the Treaty of Union 1707 with a text entitled Money and Trade Consider'd with a Proposal for Supplying the Nation with Money (1705). After the Union of the Scottish and English parliaments, Law's legal situation obliged him to go into exile again. He spent ten years moving between France and the Netherlands, dealing in financial speculations, before the problems of the French economy presented the opportunity to put his system into practice. In May 1716 the Banque Générale Privée ("General Private Bank"), which developed the use of paper money was set up by Law. It was a private bank, but three quarters of the capital consisted of government bills and government accepted notes. In August 1717, he bought the Mississippi Company, to help the French colony in Louisiana. In 1717 he also brokered the sale of Thomas Pitt's diamond to the regent, Philippe d'Orléans. In the same year Law floated the Mississippi Company as a joint stock trading company called the Compagnie d'Occident which was granted a trade monopoly of the West Indies and North America.

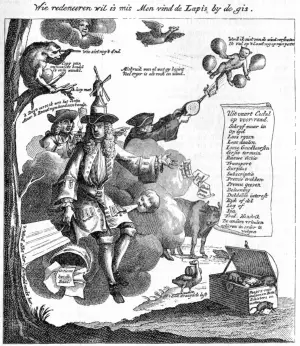

The bank became the Banque Royale (Royal Bank) in 1718, meaning the notes were guaranteed by the king. The Company absorbed the Compagnie des Indes Orientales, Compagnie de Chine, and other rival trading companies and became the Compagnie Perpetuelle des Indes on 23 May 1719 with a monopoly of commerce on all the seas. Law exaggerated the wealth of Louisiana with an effective marketing scheme, which led to wild speculation on the shares of the company in 1719. Shares rose from 500 livres in 1719 to as much as 15,000 livres in the first half of 1720, but by the summer of 1720, there was a sudden decline in confidence, leading to a 97 per cent decline in market capitalization by 1721. Predictably, the 'bubble' burst at the end of 1720, when opponents of the financier attempted en masse to convert their notes into specie. By the end of 1720 Philippe II dismissed Law, who then fled from France. Law initially moved to Brussels in impoverished circumstances. He spent the next few years gambling in Rome, Copenhagen and Venice but never regained his former prosperity. Law realised he would never return to France when Phillipe II died suddenly in 1723 and was granted permission to return to London having received a pardon in 1719. He lived in London for four years and then moved to Venice where he contracted pneumonia and died a poor man in 1729.

Law’s main theories and legacy

Water-diamond paradox

The wars of Louis XIV had left France financially destitute and with a wrecked economy. A shortage of precious metals resulted, which caused a shortage of circulating coinage and severely limited the amount of new coinage that could be minted. This was the situation when Philippe d'Orléans, the regent of France, appointed Law Controller General of Finances. His economic fame rests on two major ideas: the scarcity theory of value and the real bills doctrine of money. John Law (1705) elaborated upon Davanzati's distinction between "value in exchange" and "value in use", which led him to introduce his famous "water-diamond" paradox: namely, that water, which has great use-value, has no exchange-value while diamonds, which have great exchange-value have no use-value. However, contrary to Adam Smith (who used the same example but explained it on the basis of water and diamonds having different labor costs of production), Law regarded the relative scarcity of goods as the creator of exchange value.

Law’s System

Money, Law argued, was credit and credit was determined by the "needs of trade". Consequently, the amount of money in existence is determined not by the imports of gold or trade balances (as the Mercantilists argued), but rather on the supply of credit in the economy. And money supply (in opposition to the Quantity Theory) is endogenous, determined by the "needs of trade". Hence, he initiated the “Law’s System.” The operation involved the floating of shares in a private company, the issue of paper money, and the conversion of government debt. The System ultimately unravelled with a coincident, and dramatic, fall in the market value of both the money and the equity. Law’s System, also known as the Mississippi Bubble, represents a daring experiment in public finance, carried out by a man whom Schumpeter (1954, p. 295) placed in “the front ranks of monetary theorists of all time.”

The System had two components, one involving an operation in public finance, the other involving fiat money. The operation resulted in the conversion of the existing French public debt into a sort of government equity. Strictly speaking, a publicly traded company took over the collection of all taxes in France, ran the mints, monopolized all overseas trade and ran part of France’s colonies.

This company offered to government creditors the possibility of swapping their bonds for its equity, making itself the government’s creditor. Since it was already collecting taxes, the government’s annual payment was simply deducted from tax revenue by the company. Thus, bondholders became holders of a claim to the stochastic stream of fiscal revenues.

All the company offered was an option to convert, and visible capital gains provided a strong inducement for bondholders. As it happened, the System’s other component was a plan to replace the existing commodity money with fiat money, at first voluntarily, later based on legal restrictions.

Law used money creation to support the price of shares, and legal restrictions to support the demand for money. Inflation did not follow immediately, but exchange rate depreciation did, leading Law to reverse course and seek ultimately fruitless ways to reduce the quantity of money. The end result was a reconversion of shares and money into bonds and a return to the pre-existing arrangements.

In retrospect, Law’s System appears conceptually reasonable. Sims (2001) argues that government debt is like private debt in a fixed exchange rate regime, but like private equity in a flexible rate regime; he also thinks that the latter is preferable. France was notionally on a fixed exchange rate regime (with frequent departures); Law’s System could be interpreted as an attempt to move government debt closer to equity without sacrificing price stability. As for replacing commodity money with fiat money, what incongruity the idea held for contemporaries has clearly dispelled.

Law’s System has been called a bubble; it has also been called a default. Quantitatively, it could be seen that the share prices were overvalued at their peak by a factor of 2 to 5, but it may be attributable to Law’s systematic policy of price support. With fairly optimistic assumptions, a lower level of price support would have been feasible. As for the public debt, it was not significantly increased during the System, and it was restored by Law’s successors at roughly its earlier level.

In other words, France’s first experiment in fiat money was far from a default, perhaps surprisingly for a country otherwise prone to defaults.

Aftermath the Mississippi Bubble

In January 1720, just two weeks after John Law had been appointed as comptroller general of finance ( minister of finance), a number of large speculators decided to cash out and switch their funds into "real assets" such as property, commodities, and gold. This drove down the price of the Mississippi Company shares since the speculators could only pay for real assets with banknotes. As confidence in paper money was waning, the price of land and gold soared. This forced Law, who still enjoyed the backing of the regent, to take extraordinary measures. He prevented people from turning back to gold by proclaiming that henceforth only banknotes were legal tender. (By then the Banque Generale had practically no gold left.) At the same time, he stabilised the price of the shares of the Mississippi Company by merging the Bank Generale and the Mississippi Company, and by fixing the price of the Mississippi stock at 9,000 livres. With this measure, Law hoped that speculators would hold on to their shares and that in future the development of the American continent would prove to be so profitable as to make a large profit for the company's shareholders. However, by then, the speculators had completely lost faith in the company's shares and selling pressure continued (in fact, instead of putting a stop to the selling, the fixed price acted as an inducement to sell),which led the bank once again to increase the money supply by an enormous quantity. John Law suddenly realised that his main problem was no longer his battle against gold, which he had sought to debase, but inflation. He issued an edict by which banknotes and the shares of the Mississippi Company stock would gradually be devalued by 50%. The public reacted to this edict with fury, and shortly after Law was asked to leave the country. In the meantime, gold was again accepted as the basis of the currency, and individuals could own as much of it as they desired. Alas, as a contemporary of Law's noted, the permission came at a time when no one had any gold left. The Mississippi Scheme, which took place at about the same time as the South Sea Bubble, led to a wave of speculation in the period from 1717 to 1720 and spread across the entire European continent. When both bubbles burst, the subsequent economic crisis was international in scope.

Still, although accounts are not available about real estate prices during the monetary inflation and the subsequent bust of John Law's experiment with paper money, one might suppose that early buyers of real-estate fared better than the holders of paper money, which lost all its value. And finally, here comes the story that might serve as fitting epitaph to the scheme that, instead of being the first financial mega-success, has almost become the first international economic catastrophe: Just before he fell, John Law summoned Richard Cantillon – one of the System’s main speculators, who was threatening the "System" by converting his profits to cash and taking them out of both market and bank — to attend upon him forthwith. The story has it that Law imperiously told the Irishman: "If we were in England, we would have to negotiate with one another and come to some arrangement; in France, however, as you know, I can say to you that you will spend the night in the Bastille if you don't give me your word that you will have left the Kingdom within twice twenty-four hours." Cantillon mulled this over for a moment replied: "Very well, I shall not go, but shall help your system to success." In fact, knowing this summary treatment signalled Law’s desperation and that the end of the mania was at hand, what Cantillon did next was immediately to lend all his existing holdings of stock out to the exchange brokers. Cashing in the paper money he received in lieu of his securities, he redeemed it for gold once more and then promptly quit the country with it, to watch the unfolding collapse – and Law’s final discomfort - in ease and safety. By doing so, Cantillon inadvertently followed an important investment wisdom, which states that once an investment mania comes to an end, the best course of action is usually to exit the country or sector in which the mania took place altogether, and to move to an asset class and/or a country that has little or no correlation with the object of the previous investment boom. He also proved to be a real “entrepreneur” in the whole complicated affair.

Main bibliography and References

- Faber, Marc, The Rise to Ruin, Whiskey and Gunpowder, 2005

- Gleeson, Janet, Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance 2000 (ISBN 0-684-87295-1)

- Law, John, Considérations sur le numéraire et le commerce, 1705 (Transl. Money and Trade Considered with a Proposal for Supplying the Nation with Money)

- Law, John, Mémoire pour prouver qu'une nouvelle espèce de monnaie peut être meilleure que l'or et l'argent, 1707

- Marshall, A., Money, Credit and Commerce, London, Macmillan, 1923

- Marx, Karl, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 1, appeared in Hamburg; Volumes 2 and 3 were published by Engels in 1885 and 1894

- Mackay, C. , Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds , 1841, and still available.

- Sims, Christopher,. "A Review of Monetary Policy Rules," Journal of Economic Literature, American Economic Association, vol. 39(2), 2001,pp. 562-566

- Schumpeter, J., History of Economic Analysis, edited by E. Boody, 1954.

[edit] External links

Credits

Initial content was copied from the following Wikipedia article: All credit for producing the original text goes to the WikiMedia Foundation and its selfless team of volunteer contributors. It was copied here in compliance with the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL). Any changes made to the original text since then create a derivative work which is also GFDL licensed. Please note the current version here and at Wikipedia are liable to diverge over time. Check the edit history for details.

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.