Difference between revisions of "Jikji" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (38 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Images OK}} {{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{copyedited}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | {{Infobox Korean name| | ||

| + | hangul=백운화상초록불조직지심체요절| | ||

| + | hanja=白雲和尙抄錄佛祖直指心體要節| | ||

| + | rr=Baegun hwasang chorok buljo jikji simche yojeol| | ||

| + | mr=Paegun hwasang ch'orok pulcho chikchi simch'e yojŏl| | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | '''''Jikji''''' is the abbreviated title of a [[Korea]]n [[Buddhist]] document, whose full title can be translated as, ''The Monk Baegun's Anthology of the Great Priests' Teachings on Identification of the [[Buddha]]’s Spirit by the Practice of [[Seon]].'' An edition of ''Jikji'' printed during the [[Goryeo]] Dynasty, in 1377, is on record as the world's oldest extant movable metal print book. [[UNESCO]] confirmed ''Jikji'' as the world oldest metal type book in September 2001, and includes it in the [[Memory of the World]] program. The metal-type ''Jikji'' was published in Heungdeok Temple in 1377, 78 years prior to [[Johannes Gutenberg]]'s "42-Line Bible" printed during the years 1452-1455. An incomplete copy survives today, preserved at the Manuscrits Orientaux division of National Library of [[France]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The purpose of ''Jikji'' was to assist Buddhist monks in teaching [[Zen]] Buddhism, an undertaking in which [[Baegun]] was one of the leading figures. In fact, the type of [[Korean Buddhism|Buddhism]] taught in the work is a great deal like that of [[Zen Buddhism]], which later caught on in [[Japan]]. ''Jikji,'' as the world's oldest movable type book, is a great source of pride to modern Koreans, who view it not only as one of their many legacies to the world, but also as evidence to support their view that Korea is just as much an innovator and progressive nation as any other in the world—a testament to the great things that can be accomplished by humanity. | ||

| + | [[Image:Type set.jpg|225px|thumb|right|Metal type set used to create the Jikji, from the Jikji Museum of Printing.]] | ||

== Authorship == | == Authorship == | ||

| − | + | ''Jikji'' was written by the Buddhist monk Baegun (1298-1374, Buddhist name [[Gyeonghan]]), who served as the chief priest of Anguk and Shingwang temples in [[Haeju]], to assist in his teaching of Seon Buddhism, and the work was subsequently used by many other Buddhist teachers of his own and later periods. ''Jikji'' was first published at Seongbulsan in 1372, using [[Wood Block Printing|woodblocks]], the standard print method of the time, for which a single carved woodblock was used to print the entire text of each page. Baegun died in Chwiamsa Temple in [[Yeoju]] in 1374. There is a record indicating that in 1377, some of Baegun's disciples, including priests Seoksan and Daljam helped in the publication of a new edition of ''Jikji'' using [[movable type|movable metal type]], with financial support from the Buddhist nun Myodeok, who is believed to have turned to Buddhism after becoming disenchanted with her life in the Goryeo dynasty royal court.<ref name=MemoryWorld> Buljo jikji simche yo jeol Memory of the World Register Nomination form, Republic of Korea</ref> The fact that the metal-type ''Jikji'' was printed at such a small temple indicates that metal-type printing technology was likely already in widespread use throughout the nation.<ref name=Kim/> | |

| − | |||

| − | The fact that the Jikji was printed at such a small temple indicates that | ||

== Contents == | == Contents == | ||

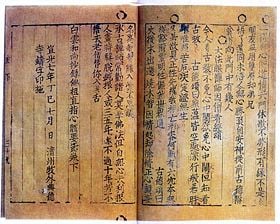

| − | + | [[Image:SelectedTeachingsofBuddhistSagesandSonMasters1377.jpg|thumb|right|280px|A page from volume two of the metal-type edition of ''Jikji'' in the collection of the National Library of France.]] | |

| + | ''Jikji'' is comprised of a collection of excerpts from the [[Lunyu|analects]] of the most revered Buddhist monks throughout successive generations. It was created as a guide for students of [[Korean Buddhism|Buddhism]], the prevailing religion in Korea during the [[Goryeo]] Dynasty (918-1392). ''Jikji'' propounds on the essentials of [[Seon]], the predecessor to Japan's [[Zen]] Buddhism. ''Jikji'' is based on the genealogy of the Chen [[Chinese Buddhism|Chinese school of Buddhism]], and includes teachings from seven Buddhas of the past, twenty-eight [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] patriarchs from India and 110 members from the Chinese genealogy of Buddhist teachers. It is comprised of 307 short texts, divided into 154 subsections and two fascicles, or volumes.<ref name=MemoryWorld/> | ||

| − | Jikji | + | The first of ''Jikji's'' two volumes deals with the recorded sayings of Indian patriarchs from the earlier stages of Buddhist history, touching on the themes of impermanence, emptiness, non-duality, Buddha-nature, wisdom, and eradication of a dualistic way of thinking. Part two comprises the thoughts of their later Chinese counterparts, touching on non-attachment, cultivation of the mind, and patriarchal Chan ({{ko icon}} ''seon''), in addition to the themes in the Indian fascicle. The first volume tends to focus on emptiness and non-attachment to words and letters. The Chan [[monk]]s, who flourished in the thirteenth century, are key figures in the second fascicle—as well as themes centering on motives of attaining [[enlightenment]], soteriology, and eradication of deluded thought.<ref>Kim Jong-myung, [http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/art/2010/04/135_63447.html Jikji: An Invaluable Text of Buddhism] ''Korea Times'', April 1, 2010. Retrieved September 28, 2020.</ref> All of these messages support the basic tenet of Buddhism, "free your mind from social status and agony, and you will find your true self inside," according to Seong-hae, a master monk at the Seoul-based Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism.<ref name=Kim>Sam Kim and Edward Targett, [https://www.buddhistchannel.tv/index.php?id=92,5772,0,0,1,0#.X3IUmmhJGUk Korea's ancient metallic printing intrigues the world] ''Yonhap News'', January 18, 2008. Retrieved September 28, 2020.</ref> |

| − | + | There is a woodblock edition of ''Jikji'' that is recorded as having been produced in June of 1378, based on the layout of the 1377 metal-type ''Jikji''. Printed at Chwiamsa Temple, the site of Master Baegun's passing into [[Nirvana]], the woodblock edition was produced under the supervision of Baegun's disciple Beublin and others, and closely resembled the metal-type edition, with a new preface added. One reason for the printing of the new edition, which was printed on [[mulberry]] paper, seems to have been that the monks at Heungdeoksa were relatively inexperienced at [[printing]], and therefore were able to print and distribute only a very limited number of copies of the metal-type edition. | |

| − | + | The only known remaining copy of the metal-print ''Jikji'' that was published in Heungdeok Temple is kept in the Manuscrits Orientaux division of the National Library of France, with the first page of the last volume (Book 1 in Chapter 38) torn off. Surviving copies of woodblock editions of ''Jikji,'' published in Chwiamsa Temple, and containing the complete two volumes can be found in the collections of the National Library of Korea and Jangsagak and Bulgap temples as well as in the Academy of Korea Studies. | |

| − | The Jikji is | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

===Printing=== | ===Printing=== | ||

| − | The Jikji was published in | + | The metal-type ''Jikji'' was published in Heungduk Temple, in Cheongju City, Chungcheong Province, in [[Korea]], in the year 1377 C.E. This means it predates the so-called Gutenberg, 42-line Bible by 78 years. As such, it is the oldest metal printed book in the world. The date can be confirmed because on the last page of "Jikji" is recorded details of its publication, indicating that it was published in the 3rd Year of [[U of Goryeo|King U]] (July 1377) by metal type at Heungdeok temple in [[Cheongju]]. The Jikji originally consisted of two volumes totaling 307 chapters, but the first volume of the metal printed version is no longer extant. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The surviving metal type volume's dimensions are 24.6 x 17.0 cm. Its paper is very slight and white. The whole text is doubly folded very slightly. The cover looks re-made. The title of ''Jikji'' also seems to be written with an Indian ink after the original. The cover also contains a note in French, "This is the oldest printed book with molded type," written by Maurice Courant. |

| − | + | The lines are not straight, but askew. There is a substantial difference in the thickness of the [[ink]] color from section to section, and frequent inkspots and blurs near some of the characters. Even some characters, such as "day" (日) or "one" (一), are written in reverse, while other letters are not printed out completely. Due to the fact that no pairs of identical characters are found on the same page, whereas identical characters can be identified on separate pages, it can be concluded that the characters were not cast in multiples, but each was produced singly, suggesting that they were cast from [[beeswax]] molds, rather than a sand-casting method, which would have allowed for the creation of duplicates. | |

===National Library of France=== | ===National Library of France=== | ||

| − | Toward the end of the [[Joseon Dynasty]], a French diplomat took the second volume of the Jikji from Korea to France | + | Toward the end of the [[Joseon Dynasty]], a French diplomat took the second volume of the Jikji from Korea to France. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | According to [[UNESCO]] records, the Jikji “had been in the collection of (Victor Emile Marie Joseph) Collin de Plancy (1853-1924), a chargé d’affaires with the French [[Embassy]] in [[Seoul]] during the reign of [[Emperor Gojong of Korea|King Gojong]]. It was de Plancy who served as the first French consul to Korea, after Korea and France concluded a treaty of defense and commerce in May 1886, which resulted in the establishment of official [[diplomatic relations]] between the two countries. The [[treaty]] was officially ratified by Kim Yunsik (1835-1922) and de Plancy, who had majored in law in France and went on to study Chinese. Having previously served as translator at the France Legation in [[China]] for six years from 1877. In 1888, de Clancy's began his term as the first French consul to Korea, a post he held until 1891. During his extended residence in Korea, first as consul and then again as full diplomatic minister from 1896-1906, Victor Collin de Plancy collected Korean [[ceramics]] and old [[book]]s. He let Kulang, who had moved to Seoul as his official secretary, classify them. | |

| − | Although the channels through which Plancy collected his works are not clearly known, he seems to have had collected them mostly beginning from the early 1900s. Most of old books Plancy collected in Korea went to the National Library of France at an auction in 1911, while the metal printed Jikji was purchased in that same year for 180 francs by Henri Véver (1854-1943), a well-known jewel merchant and old book collector, who in turn donated it to the French National Library in his will. | + | Although the channels through which de Plancy collected his works are not clearly known, he seems to have had collected them mostly beginning from the early 1900s. Most of old books Plancy collected in Korea went to the National Library of France at an auction in 1911, while the metal printed ''Jikji'' was purchased in that same year for 180 francs, in an auction at Hotel Drouot, by Henri Véver (1854-1943), a well-known jewel merchant and old book collector, who in turn donated it to the French National Library in his ''will''. Today, only 38 sheets of the second volume of the metal print edition are extant.<ref>Sun-Young Kwak, World Heritage Rights Versus National Cultural Property Rights: The Case Of The ''Jikji'' Carnegie Council, April 22, 2005.</ref> |

===Rediscovery=== | ===Rediscovery=== | ||

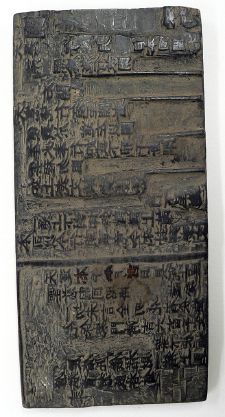

| − | The metal printed Jikji became known to the world in 1901, through its inclusion in the appendix of the ''Hanguk Seoji,'' compiled by the French Sinologist and scholar of Korea, Maurice Courant(1865-1935). In 1972 the Jikji was displayed in Paris during the "International Book Year" hosted by the [[National Library of France]], gaining it worldwide attention for the first time. | + | [[Image:Korean woodblock.jpg|225px|right|thumb|A Korean woodblock of the type in use when Jikji was printed]] |

| + | The metal printed ''Jikji'' became known to the world in 1901, through its inclusion in the appendix of the ''Hanguk Seoji,'' compiled by the French Sinologist and scholar of Korea, Maurice Courant (1865-1935). In 1972, the ''Jikji'' was displayed in Paris during the "International Book Year" hosted by the [[National Library of France]], gaining it worldwide attention for the first time. | ||

| − | The Jikji was printed using metal print in Hungdeok Temple outside Cheongjumok in July 1377, | + | The fact that ''Jikji'' was printed using metal print in Hungdeok Temple outside Cheongjumok in July 1377, is recorded in its postscript. The fact that it was printed in Heungdeoksa Temple in Uncheondong Cheongju was confirmed when Cheongju University excavated the Heungdeoksa Temple site in 1985. |

| − | + | Heungdeoksa Temple was rebuilt in March 1992. In 1992, the Early Printing Museum of Cheongju was opened, and it took ''Jikji'' as its central theme from 2000. Only the final volume of the ''Jikji'' is preserved by the Manuscrits Orienteux department of the France National Library. On September 4, 2001, ''Jikji'' was formally added to the [[UNESCO|UNESCO's]] [[Memory of the World]]. | |

==Cultural significance== | ==Cultural significance== | ||

| − | The Gutenberg Bible | + | The Gutenberg [[Bible]], significant because it is the earliest movable type book produced in the West, has also long been held to be a revolutionary linchpin in the development of Western Civilization. It helped break down social barriers and stomp out corruption in the Church. It led to major upheaval in Europe. The ''Jikji'' is also historically significant as a pioneer printing work; and it, too, was produced to help deliver an ideological, this one focusing mainly on the teaching of [[Zen]] Buddhism, aiming to help overcome human psychological anguish and help people reach inner freedom. |

| − | + | When the ''Jikji'' was named a UNESCO Memory of the World, it forced the history of printing to be rewritten. According to Yoo Chang-jun, a senior publisher at the Korean Printers Association in Seoul, "It startled the world because no one thought an obscure Far Eastern country would have developed metallic printing far ahead of Gutenberg." There is some speculation that, thanks to the [[Mongolian Empire]] of the time, which stretched from Korea to [[Europe]], the ''Jikji'' technology may have inspired the Gutenberg press. There is, however, no evidence to support this. | |

| − | + | The ''Jikji'' is an important source of pride for Koreans. The fact that the project would not have been realize without the financial support of a female monk displays a great degree of progressiveness, especially for the fourteenth century. Korea strives to live up to that legacy, through the '''UNESCO ''Jikji'' Memory of the World Prize,''' given out biannually to individuals or groups who make significant contributions to the preservation and accessibility of documentary heritage. In 2007, the $30,000 award was given to the [[Vienna]]-based Austrian Academy of Sciences, in recognition of its commitment to the preservation of audiovisual research archives.<ref name=Kim/> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ''Jikji'' is recorded as [[National treasures of South Korea|South Korean National Treasure]] #1132. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

*Greenfield, Jeanette. ''The Return of Cultural Treasures.'' Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0521802161. | *Greenfield, Jeanette. ''The Return of Cultural Treasures.'' Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0521802161. | ||

*Haeoe Munhwa Hongbowon. ''Handbook of Korea.'' Hollym International Corporation, 2004. ISBN 978-1565912120. | *Haeoe Munhwa Hongbowon. ''Handbook of Korea.'' Hollym International Corporation, 2004. ISBN 978-1565912120. | ||

| + | *Kyŏnghan, John Jorgensen, and Eu-su Cho. ''Jikji: The Essential Passages Directly Pointing at the Essence of the Mind''. Cheongju, South Korea: Cheongju City Office, 2006. OCLC 191729792. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Technology]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Literature]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{Credits|227505908}} | + | {{Credits|Jikji|227505908|직지|2129336}} |

Latest revision as of 01:10, 9 February 2023

| Jikji | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Jikji is the abbreviated title of a Korean Buddhist document, whose full title can be translated as, The Monk Baegun's Anthology of the Great Priests' Teachings on Identification of the Buddha’s Spirit by the Practice of Seon. An edition of Jikji printed during the Goryeo Dynasty, in 1377, is on record as the world's oldest extant movable metal print book. UNESCO confirmed Jikji as the world oldest metal type book in September 2001, and includes it in the Memory of the World program. The metal-type Jikji was published in Heungdeok Temple in 1377, 78 years prior to Johannes Gutenberg's "42-Line Bible" printed during the years 1452-1455. An incomplete copy survives today, preserved at the Manuscrits Orientaux division of National Library of France.

The purpose of Jikji was to assist Buddhist monks in teaching Zen Buddhism, an undertaking in which Baegun was one of the leading figures. In fact, the type of Buddhism taught in the work is a great deal like that of Zen Buddhism, which later caught on in Japan. Jikji, as the world's oldest movable type book, is a great source of pride to modern Koreans, who view it not only as one of their many legacies to the world, but also as evidence to support their view that Korea is just as much an innovator and progressive nation as any other in the world—a testament to the great things that can be accomplished by humanity.

Authorship

Jikji was written by the Buddhist monk Baegun (1298-1374, Buddhist name Gyeonghan), who served as the chief priest of Anguk and Shingwang temples in Haeju, to assist in his teaching of Seon Buddhism, and the work was subsequently used by many other Buddhist teachers of his own and later periods. Jikji was first published at Seongbulsan in 1372, using woodblocks, the standard print method of the time, for which a single carved woodblock was used to print the entire text of each page. Baegun died in Chwiamsa Temple in Yeoju in 1374. There is a record indicating that in 1377, some of Baegun's disciples, including priests Seoksan and Daljam helped in the publication of a new edition of Jikji using movable metal type, with financial support from the Buddhist nun Myodeok, who is believed to have turned to Buddhism after becoming disenchanted with her life in the Goryeo dynasty royal court.[1] The fact that the metal-type Jikji was printed at such a small temple indicates that metal-type printing technology was likely already in widespread use throughout the nation.[2]

Contents

Jikji is comprised of a collection of excerpts from the analects of the most revered Buddhist monks throughout successive generations. It was created as a guide for students of Buddhism, the prevailing religion in Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). Jikji propounds on the essentials of Seon, the predecessor to Japan's Zen Buddhism. Jikji is based on the genealogy of the Chen Chinese school of Buddhism, and includes teachings from seven Buddhas of the past, twenty-eight Buddhist patriarchs from India and 110 members from the Chinese genealogy of Buddhist teachers. It is comprised of 307 short texts, divided into 154 subsections and two fascicles, or volumes.[1]

The first of Jikji's two volumes deals with the recorded sayings of Indian patriarchs from the earlier stages of Buddhist history, touching on the themes of impermanence, emptiness, non-duality, Buddha-nature, wisdom, and eradication of a dualistic way of thinking. Part two comprises the thoughts of their later Chinese counterparts, touching on non-attachment, cultivation of the mind, and patriarchal Chan ((Korean) seon), in addition to the themes in the Indian fascicle. The first volume tends to focus on emptiness and non-attachment to words and letters. The Chan monks, who flourished in the thirteenth century, are key figures in the second fascicle—as well as themes centering on motives of attaining enlightenment, soteriology, and eradication of deluded thought.[3] All of these messages support the basic tenet of Buddhism, "free your mind from social status and agony, and you will find your true self inside," according to Seong-hae, a master monk at the Seoul-based Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism.[2]

There is a woodblock edition of Jikji that is recorded as having been produced in June of 1378, based on the layout of the 1377 metal-type Jikji. Printed at Chwiamsa Temple, the site of Master Baegun's passing into Nirvana, the woodblock edition was produced under the supervision of Baegun's disciple Beublin and others, and closely resembled the metal-type edition, with a new preface added. One reason for the printing of the new edition, which was printed on mulberry paper, seems to have been that the monks at Heungdeoksa were relatively inexperienced at printing, and therefore were able to print and distribute only a very limited number of copies of the metal-type edition.

The only known remaining copy of the metal-print Jikji that was published in Heungdeok Temple is kept in the Manuscrits Orientaux division of the National Library of France, with the first page of the last volume (Book 1 in Chapter 38) torn off. Surviving copies of woodblock editions of Jikji, published in Chwiamsa Temple, and containing the complete two volumes can be found in the collections of the National Library of Korea and Jangsagak and Bulgap temples as well as in the Academy of Korea Studies.

History

Printing

The metal-type Jikji was published in Heungduk Temple, in Cheongju City, Chungcheong Province, in Korea, in the year 1377 C.E. This means it predates the so-called Gutenberg, 42-line Bible by 78 years. As such, it is the oldest metal printed book in the world. The date can be confirmed because on the last page of "Jikji" is recorded details of its publication, indicating that it was published in the 3rd Year of King U (July 1377) by metal type at Heungdeok temple in Cheongju. The Jikji originally consisted of two volumes totaling 307 chapters, but the first volume of the metal printed version is no longer extant.

The surviving metal type volume's dimensions are 24.6 x 17.0 cm. Its paper is very slight and white. The whole text is doubly folded very slightly. The cover looks re-made. The title of Jikji also seems to be written with an Indian ink after the original. The cover also contains a note in French, "This is the oldest printed book with molded type," written by Maurice Courant.

The lines are not straight, but askew. There is a substantial difference in the thickness of the ink color from section to section, and frequent inkspots and blurs near some of the characters. Even some characters, such as "day" (日) or "one" (一), are written in reverse, while other letters are not printed out completely. Due to the fact that no pairs of identical characters are found on the same page, whereas identical characters can be identified on separate pages, it can be concluded that the characters were not cast in multiples, but each was produced singly, suggesting that they were cast from beeswax molds, rather than a sand-casting method, which would have allowed for the creation of duplicates.

National Library of France

Toward the end of the Joseon Dynasty, a French diplomat took the second volume of the Jikji from Korea to France.

According to UNESCO records, the Jikji “had been in the collection of (Victor Emile Marie Joseph) Collin de Plancy (1853-1924), a chargé d’affaires with the French Embassy in Seoul during the reign of King Gojong. It was de Plancy who served as the first French consul to Korea, after Korea and France concluded a treaty of defense and commerce in May 1886, which resulted in the establishment of official diplomatic relations between the two countries. The treaty was officially ratified by Kim Yunsik (1835-1922) and de Plancy, who had majored in law in France and went on to study Chinese. Having previously served as translator at the France Legation in China for six years from 1877. In 1888, de Clancy's began his term as the first French consul to Korea, a post he held until 1891. During his extended residence in Korea, first as consul and then again as full diplomatic minister from 1896-1906, Victor Collin de Plancy collected Korean ceramics and old books. He let Kulang, who had moved to Seoul as his official secretary, classify them.

Although the channels through which de Plancy collected his works are not clearly known, he seems to have had collected them mostly beginning from the early 1900s. Most of old books Plancy collected in Korea went to the National Library of France at an auction in 1911, while the metal printed Jikji was purchased in that same year for 180 francs, in an auction at Hotel Drouot, by Henri Véver (1854-1943), a well-known jewel merchant and old book collector, who in turn donated it to the French National Library in his will. Today, only 38 sheets of the second volume of the metal print edition are extant.[4]

Rediscovery

The metal printed Jikji became known to the world in 1901, through its inclusion in the appendix of the Hanguk Seoji, compiled by the French Sinologist and scholar of Korea, Maurice Courant (1865-1935). In 1972, the Jikji was displayed in Paris during the "International Book Year" hosted by the National Library of France, gaining it worldwide attention for the first time.

The fact that Jikji was printed using metal print in Hungdeok Temple outside Cheongjumok in July 1377, is recorded in its postscript. The fact that it was printed in Heungdeoksa Temple in Uncheondong Cheongju was confirmed when Cheongju University excavated the Heungdeoksa Temple site in 1985.

Heungdeoksa Temple was rebuilt in March 1992. In 1992, the Early Printing Museum of Cheongju was opened, and it took Jikji as its central theme from 2000. Only the final volume of the Jikji is preserved by the Manuscrits Orienteux department of the France National Library. On September 4, 2001, Jikji was formally added to the UNESCO's Memory of the World.

Cultural significance

The Gutenberg Bible, significant because it is the earliest movable type book produced in the West, has also long been held to be a revolutionary linchpin in the development of Western Civilization. It helped break down social barriers and stomp out corruption in the Church. It led to major upheaval in Europe. The Jikji is also historically significant as a pioneer printing work; and it, too, was produced to help deliver an ideological, this one focusing mainly on the teaching of Zen Buddhism, aiming to help overcome human psychological anguish and help people reach inner freedom.

When the Jikji was named a UNESCO Memory of the World, it forced the history of printing to be rewritten. According to Yoo Chang-jun, a senior publisher at the Korean Printers Association in Seoul, "It startled the world because no one thought an obscure Far Eastern country would have developed metallic printing far ahead of Gutenberg." There is some speculation that, thanks to the Mongolian Empire of the time, which stretched from Korea to Europe, the Jikji technology may have inspired the Gutenberg press. There is, however, no evidence to support this.

The Jikji is an important source of pride for Koreans. The fact that the project would not have been realize without the financial support of a female monk displays a great degree of progressiveness, especially for the fourteenth century. Korea strives to live up to that legacy, through the UNESCO Jikji Memory of the World Prize, given out biannually to individuals or groups who make significant contributions to the preservation and accessibility of documentary heritage. In 2007, the $30,000 award was given to the Vienna-based Austrian Academy of Sciences, in recognition of its commitment to the preservation of audiovisual research archives.[2]

Jikji is recorded as South Korean National Treasure #1132.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Buljo jikji simche yo jeol Memory of the World Register Nomination form, Republic of Korea

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Sam Kim and Edward Targett, Korea's ancient metallic printing intrigues the world Yonhap News, January 18, 2008. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ↑ Kim Jong-myung, Jikji: An Invaluable Text of Buddhism Korea Times, April 1, 2010. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ↑ Sun-Young Kwak, World Heritage Rights Versus National Cultural Property Rights: The Case Of The Jikji Carnegie Council, April 22, 2005.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- English, Alex, and Robert Storey. Lonely Planet Korea. Lonely Planet Publications, 2001. ISBN 978-0864426970.

- Greenfield, Jeanette. The Return of Cultural Treasures. Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0521802161.

- Haeoe Munhwa Hongbowon. Handbook of Korea. Hollym International Corporation, 2004. ISBN 978-1565912120.

- Kyŏnghan, John Jorgensen, and Eu-su Cho. Jikji: The Essential Passages Directly Pointing at the Essence of the Mind. Cheongju, South Korea: Cheongju City Office, 2006. OCLC 191729792.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.