Indian inscriptions

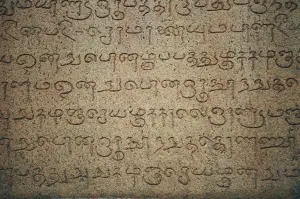

The earliest traces of epigraphy in South Asia are found in Sri Lanka, dating to ca. the 6th century B.C.E. (Tamil Brahmi). Inscriptions in the Brahmi script also appear on the Indian subcontinent proper, from about the 3rd century B.C.E. (Ashoka inscriptions). Indian epigraphy becomes more widespread over the 1st millennium AD, engraved on the faces of cliffs, on pillars, on tablets of stone, drawn in caves and on rocks, some gouged into the bedrock. Later they were also inscribed on palm leaves, coins, copper plates, and on temple walls.

Many of the inscriptions are couched in extravagant language, but when the information gained from inscriptions can be corroborated with information from other sources such as still existing monuments or ruins, inscriptions provide insight into India's dynastic history that otherwise lacks contemporary historical records.[1]

More than 55% of the epigraphical inscriptions, about 55,000, found by the Archaeological Survey of India in India are in Tamil language[2]

History and Research

Since 1886 there have been systematic attempts to collect and catalogue these inscriptions, along with the translation and publication of documents.[3] Inscriptions may be in Brāhmī script or Tamil-Brahmi script or Kannada script or even the still undeciphered Indus script. Royal inscriptions were also engraved on copper-plates as were the Copper-plate grant. Tamil-Brahmi was an early script used in the inscriptions on Edicts of Ashoka and later evolved into the Tamil Vatteluttu script.[4]

Notable inscriptions

Important inscriptions include the 33 inscriptions of emperor Ashoka on the Pillars of Ashoka (272 to 231 B.C.E.), Hathigumpha inscription, the Rabatak inscription, the Kannada Halmidi inscription, and the Tamil copper-plate inscriptions. The oldest known inscription in the Kannada language, referred to as the Halmidi inscription for the tiny village of Halmidi near where it was found, consists of sixteen lines carved on a sandstone pillar and dates to 450 C.E.[5]

Hathigumpha inscription

The Hathigumpha inscription ("Elephant Cave" inscription) from Udayagiri near Bhubaneshwar in Orissa was written by Kharavela, the king of Kalinga in India during the 2nd century B.C.E. The Hathigumpha inscription consists of seventeen lines incised in deep cut Brahmi letters on the overhanging brow of a natural cavern called Hathigumpha on the southern side of the Udayagiri hill near Bhubaneswar in Orissa. It faces straight toward the rock Edicts of Asoka at Dhauli located about six miles away.

Rabatak inscription

The Rabatak inscription is written on a rock in the Bactrian language and Greek script and found in 1993 at the site of Rabatak, near Surkh Kotal in Afghanistan. The inscription relates to the rule of the Kushan emperor Kanishka and gives remarkable clues to the genealogy of the Kushan dynasty.

Halmidi inscription

The Halmidi inscription is the oldest known inscription in the Kannada script. The inscription is carved on a pillar, that was discovered in the village of Halmidi, a few miles from the famous temple town of Belur in the Hassan district of Karnataka, and is dated 450 C.E. The original inscription has now been deposited in an archaeological museum in Bangalore while a fibreglass replica has been installed in Halmidi.

Tamil copper-plate inscriptions

Tamil copper-plate inscriptions are mostly records of grants of villages or plots of cultivable lands to private individuals or public institutions by the members of the various South Indian royal dynasties. The grants range in date from the 10th century C.E. to the mid 19th century C.E. A large number of them belong to the Chalukyas, the Cholas and the Vijayanagar kings. These plates are valuable epigraphically as they give us an insight into the social conditions of medieval South India and help fill chronological gaps to connect the history of the ruling dynasties.

Unlike the neighbouring Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh where early inscriptions were written in Sanskrit, the early inscriptions in Tamil Nadu used Tamil exclusively.[6] Tamil has the oldest extant literature amongst the Dravidian languages, but dating the language and the literature precisely is difficult. Literary works in India were preserved either in palm leaf manuscripts (implying repeated copying and recopying) or through oral transmission, making direct dating impossible.[7] External chronological records and internal linguistic evidence, however, indicate that the oldest extant works were probably compiled sometime between the 2nd century B.C.E. and the 10th century AD.[8][9][10] Epigraphic attestation of Tamil begins with rock inscriptions from the 2nd century B.C.E., written in Tamil-Brahmi, an adapted form of the Brahmi script.[11][12] The earliest extant literary text is the Tolkāppiyam, a work on poetics and grammar which describes the language of the classical period, dated variously between the 1st BC and tenth AD.

See also

- Indus script

- Ashoka's Major Rock Edict

- Indian copper plate inscriptions

- Brāhmī script

- Ancient inscriptions Of Raju Rulers

- Heliodorus pillar

- Kammanadu

- Nagarattar

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Keay, John (2000). India: A History. New York: Grove Press, pp xx - xxi. ISBN 0802137970.

- ↑ Staff Reporter (November 22 2005). Students get glimpse of heritage. The Hindu. Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- ↑ Indian inscriptions. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Orality to literacy: Transition in Early Tamil Society. Frontline. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Halmidi village finally on the road to recognition. The Hindu. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Caldwell, Robert (1875). A comparative grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian family of languages. Trübner & co, 88. “In Karnataka and Telingana, every inscription of an early date and majority even of modern day inscriptions are written in Sanskrit...In the Tamil country, on the contrary, all the inscriptions belonging to an early period are written in Tamil”

- ↑ Dating of Indian literature is largely based on relative dating relying on internal evidences with a few anchors. I. Mahadevan’s dating of Pukalur inscription proves some of the Sangam verses. See George L. Hart, "Poems of Ancient Tamil, University of Berkeley Press, 1975, p.7-8

- ↑ George Hart, "Some Related Literary Conventions in Tamil and Indo-Aryan and Their Significance" Journal of the American Oriental Society, 94:2 (Apr - Jun 1974), pp. 157-167.

- ↑ Kamil Veith Zvelebil, Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, pp12

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. (1955). A History of South India, OUP, New Delhi (Reprinted 2002)

- ↑ Tamil. The Language Materials Project. UCLA International Institute, UCLA. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ↑ Iravatham Mahadevan (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century C.E. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.