Difference between revisions of "Hollow-Face illusion" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| − | + | ||

The '''Hollow-Face illusion''' is an [[optical illusion]] in which the perception of a concave mask of a face appears as a normal convex face. | The '''Hollow-Face illusion''' is an [[optical illusion]] in which the perception of a concave mask of a face appears as a normal convex face. | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

==Discovery== | ==Discovery== | ||

The hollow face illusion was first brought to the public's attention by Richard Gregory, who published it in ''Illusion in Nature and Art'' in 1973. | The hollow face illusion was first brought to the public's attention by Richard Gregory, who published it in ''Illusion in Nature and Art'' in 1973. | ||

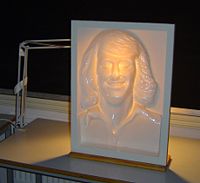

| − | + | [[Image:Bjorn Borg Hollow Face.jpg|200px|thumb|right|This face of [[Björn Borg]] appears convex, (pushed out) but is actually concave (pushed in).]] | |

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

While a convex face can appear to look in a single direction, and a flat face such as the [[Lord Kitchener Wants You]] poster can appear to follow the moving viewer, a hollow face can appear to move its eyes faster than the viewer: looking forward when the viewer is directly ahead, but looking at an extreme angle when the viewer is only at a moderate angle. Thus, changing the viewing angle of a hollow face can dramatically change the apparent orientation of the face itself. Where a two dimensional figure can appear to follow the viewers movements, the hollow face actually appears to swivel. | While a convex face can appear to look in a single direction, and a flat face such as the [[Lord Kitchener Wants You]] poster can appear to follow the moving viewer, a hollow face can appear to move its eyes faster than the viewer: looking forward when the viewer is directly ahead, but looking at an extreme angle when the viewer is only at a moderate angle. Thus, changing the viewing angle of a hollow face can dramatically change the apparent orientation of the face itself. Where a two dimensional figure can appear to follow the viewers movements, the hollow face actually appears to swivel. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Another example of the Hollow-Face illusion is found in a popular folded paper cutout of a dog or dragon. This dragon's head seems to follow the viewer's eyes everywhere (even up or down), when lighting, perspective and/or stereoscopic cues are not strong enough to tell its face is actually hollow. Keen observers will note that the head doesn't actually follow them, but appears to turn ''twice'' as fast around its center than they do themselves. A version of this cut out dragon can be printed from: [http://www.grand-illusions.com/images/articles/opticalillusions/dragon_illusion/dragon.pdf Dragon Illusion] (PDF). | Another example of the Hollow-Face illusion is found in a popular folded paper cutout of a dog or dragon. This dragon's head seems to follow the viewer's eyes everywhere (even up or down), when lighting, perspective and/or stereoscopic cues are not strong enough to tell its face is actually hollow. Keen observers will note that the head doesn't actually follow them, but appears to turn ''twice'' as fast around its center than they do themselves. A version of this cut out dragon can be printed from: [http://www.grand-illusions.com/images/articles/opticalillusions/dragon_illusion/dragon.pdf Dragon Illusion] (PDF). | ||

| + | [[Image:Hollow dragon front.jpg|300px|thumb|left|A paper hollow face dragon, shown from four angles across the 90 degree effective viewing area]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Hollow dragon back.jpg|200px|thumb|right|The back of the paper dragon]] | ||

==Explanation== | ==Explanation== | ||

Humans have a great amount of bias towards seeing faces as convex. This bias is so strong that it counters competing monocular depth cues such as shading and shadows, as well as considerable stereoscopic depth cues. The effect of the hollow face illusion is the weakest when the face is viewed upside down, and strongest when in the most commonly viewed, right side up orientation.<ref>Gregory, Richard. [[http://www.richardgregory.org/papers/knowl_illusion/knowledge-in-perception.htm "Knowledge in perception and illusion"]] University of Bristol. 1997. Retrieved October 9, 2007.</ref> Lighting a concave face from below to reverse the shading cues making them closer to those of a convex face lit from above can reinforce the illusion. | Humans have a great amount of bias towards seeing faces as convex. This bias is so strong that it counters competing monocular depth cues such as shading and shadows, as well as considerable stereoscopic depth cues. The effect of the hollow face illusion is the weakest when the face is viewed upside down, and strongest when in the most commonly viewed, right side up orientation.<ref>Gregory, Richard. [[http://www.richardgregory.org/papers/knowl_illusion/knowledge-in-perception.htm "Knowledge in perception and illusion"]] University of Bristol. 1997. Retrieved October 9, 2007.</ref> Lighting a concave face from below to reverse the shading cues making them closer to those of a convex face lit from above can reinforce the illusion. | ||

| + | [[Image:HollowfaceillusionBarcelona.JPG|200px|thumb|right|An example of a hollow-face illusion outside of a bank in [[Barcelona]]]] | ||

==Applications== | ==Applications== | ||

It is interesting to note that viewers see the hollow face as concave even though they consciously know that it is hollow. Psychologists and other scientists can use the perception of illusions such as the hollow face illusion to examine the relationships between perception and knowledge, as well as study the way the brain perceives such illusions. | It is interesting to note that viewers see the hollow face as concave even though they consciously know that it is hollow. Psychologists and other scientists can use the perception of illusions such as the hollow face illusion to examine the relationships between perception and knowledge, as well as study the way the brain perceives such illusions. | ||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == References == | ||

*[http://www.richardgregory.org/papers/knowl_illusion/knowledge-in-perception.htm "Knowledge in perception and illusion"] by Richard Gregory, ''Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B (1997) 352, 1121–1128'' - authoritative introduction to optical illusions. | *[http://www.richardgregory.org/papers/knowl_illusion/knowledge-in-perception.htm "Knowledge in perception and illusion"] by Richard Gregory, ''Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B (1997) 352, 1121–1128'' - authoritative introduction to optical illusions. | ||

Revision as of 15:09, 10 October 2007

The Hollow-Face illusion is an optical illusion in which the perception of a concave mask of a face appears as a normal convex face.

Discovery

The hollow face illusion was first brought to the public's attention by Richard Gregory, who published it in Illusion in Nature and Art in 1973.

Description

While a convex face can appear to look in a single direction, and a flat face such as the Lord Kitchener Wants You poster can appear to follow the moving viewer, a hollow face can appear to move its eyes faster than the viewer: looking forward when the viewer is directly ahead, but looking at an extreme angle when the viewer is only at a moderate angle. Thus, changing the viewing angle of a hollow face can dramatically change the apparent orientation of the face itself. Where a two dimensional figure can appear to follow the viewers movements, the hollow face actually appears to swivel.

The hollow face illusion works best with monocular vision; filming with a camera or closing one eye to remove stereoscopic depth cues greatly enhances the illusion.

Another example of the Hollow-Face illusion is found in a popular folded paper cutout of a dog or dragon. This dragon's head seems to follow the viewer's eyes everywhere (even up or down), when lighting, perspective and/or stereoscopic cues are not strong enough to tell its face is actually hollow. Keen observers will note that the head doesn't actually follow them, but appears to turn twice as fast around its center than they do themselves. A version of this cut out dragon can be printed from: Dragon Illusion (PDF).

Explanation

Humans have a great amount of bias towards seeing faces as convex. This bias is so strong that it counters competing monocular depth cues such as shading and shadows, as well as considerable stereoscopic depth cues. The effect of the hollow face illusion is the weakest when the face is viewed upside down, and strongest when in the most commonly viewed, right side up orientation.[1] Lighting a concave face from below to reverse the shading cues making them closer to those of a convex face lit from above can reinforce the illusion.

Applications

It is interesting to note that viewers see the hollow face as concave even though they consciously know that it is hollow. Psychologists and other scientists can use the perception of illusions such as the hollow face illusion to examine the relationships between perception and knowledge, as well as study the way the brain perceives such illusions.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- "Knowledge in perception and illusion" by Richard Gregory, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B (1997) 352, 1121–1128 - authoritative introduction to optical illusions.

- Frith, Chris. Making up the Mind: How the Brain Creates Our Mental World April 2007. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1405160225

- Perlman, M. Conceptual Flux - Mental Representation, Misrepresentation, and Concept Change (STUDIES IN COGNITIVE SYSTEMS Volume 24) February 2002. Springer. ISBN 0792362152

External links

- "The Hollow Face Illusion" at Grand Illusions

- Dragon illusion

- Richard Gregory

- Templates for the Dragon Illusion in different colors

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Gregory, Richard. ["Knowledge in perception and illusion"] University of Bristol. 1997. Retrieved October 9, 2007.