Difference between revisions of "Heloise" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Early Life) |

|||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

==Early Life== | ==Early Life== | ||

| + | |||

| + | From Ableard's writings most believe that Heloise was raised in the nunnery of Argenteuil, where her mother, Hersinde, lived. There is no record about her father. From the Paraclete necrology roll (an obituary that was sent after the death of person for acquaintances to write messages and then kept as a memorial of the person's death) we understand that her Heloise and her mother lived in the nunnery. There is no record of Heloise's legitimate birth. Her mother could have been married, could have been a formal concubine or just an unwed mother. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this period, many wealthy women chose to live in monasteries. Widows and women with children, without a male protector, often found a safe haven in the monastic environment. They were like "renters" within the monastic community participating in the religious life yet not necessarily taking vows. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Women could receive education in this environment while the other institutional structures increasingly denied them this opportunity up until the late nineteenth century. | ||

| + | |||

| + | During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, male primogeniture was established. This allowed the eldest son to inherit all the property instead of cutting it up among all the offspring, thus keeping it intact for the family. Other sons then were sent off to soldiering or scholarship or monastic life. Families believed that the monastic life was a "hero's" life and the prayers of the priest or monk would protect them and allow them a better passage into the next life. In this atmosphere women became increasingly left out of opportunities of inheritance and education. As celibacy became the official standard for priests and monks women were also put into two categories: Eve, temptress and the cause of the fall of man, and Mary, holy women living in seclusion and not tempting men. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We don't know of Heloise's education, but even in her youth she was considered a "rara avis"<ref 1><''Medieval Heroines in History and Legend'', Bonnie Wheeler><ref> | ||

| + | |||

[[Image:Heloise World Noted Women.jpg|right|thumb|right|Heloïse imagined in a mid-19<sup>th</sup> century engraving]] | [[Image:Heloise World Noted Women.jpg|right|thumb|right|Heloïse imagined in a mid-19<sup>th</sup> century engraving]] | ||

Revision as of 15:47, 5 May 2007

The letters of Heloïse (1101-1162) and Pierre Abélard are among the best known records of early romantic love.

Though Heloïse (also spelled Héloise, Hélose, Heloisa, and Helouisa, among other variations) is best known for her relationship with Peter Abélard, she was a brilliant scholar of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew and had a reputation for intelligence and insight. Not a great deal is known of her immediate family except that in her letters she implies she is of a lower social standing (probably the Garlande family who had money and several members in strong positions) than was Abélard, who was from the nobility.

What is known is that she was the ward of an uncle, a canon in Paris named Fulbert, and by the age of 18 she had become the student of Pierre Abélard who was one of the most popular teachers and philosophers in Paris.

In his writings, Abélard tells the story of his seduction of Heloïse, their secret marriage, the birth of a son, Astrolabius (in English, "Astrolabe"), and of his castration by her furious guardian, after which Heloïse entered a convent in Argenteuil.

At the convent in Argenteuil, Heloïse eventually became prioress. She and the other nuns were turned out when the convent was taken over, at which point Abélard arranged for them to enter the Oratory of the Paraclete, an abbey he had established, and Heloïse became the abbess there. It is from here that her contributions to monastic life for women were made.

Early Life

From Ableard's writings most believe that Heloise was raised in the nunnery of Argenteuil, where her mother, Hersinde, lived. There is no record about her father. From the Paraclete necrology roll (an obituary that was sent after the death of person for acquaintances to write messages and then kept as a memorial of the person's death) we understand that her Heloise and her mother lived in the nunnery. There is no record of Heloise's legitimate birth. Her mother could have been married, could have been a formal concubine or just an unwed mother.

In this period, many wealthy women chose to live in monasteries. Widows and women with children, without a male protector, often found a safe haven in the monastic environment. They were like "renters" within the monastic community participating in the religious life yet not necessarily taking vows.

Women could receive education in this environment while the other institutional structures increasingly denied them this opportunity up until the late nineteenth century.

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, male primogeniture was established. This allowed the eldest son to inherit all the property instead of cutting it up among all the offspring, thus keeping it intact for the family. Other sons then were sent off to soldiering or scholarship or monastic life. Families believed that the monastic life was a "hero's" life and the prayers of the priest or monk would protect them and allow them a better passage into the next life. In this atmosphere women became increasingly left out of opportunities of inheritance and education. As celibacy became the official standard for priests and monks women were also put into two categories: Eve, temptress and the cause of the fall of man, and Mary, holy women living in seclusion and not tempting men.

We don't know of Heloise's education, but even in her youth she was considered a "rara avis"<ref 1><Medieval Heroines in History and Legend, Bonnie Wheeler><ref>

Seduction by Abelard

Life after Abelard's Castration

It was at about this time that a correspondence between the two former lovers sprang up. Heloïse encouraged Abélard in his philosophical work, and he dedicated his profession of faith to her. Heloise lamented her loss of Abelard's love, both sexual and intellectual or spiritual.

In his shame, after being castrated, he insists that he will relate to her only as she is the "beloved of Christ."

The Problemata Heloissae (Heloise's Problems) are a collection of 42 theological questions directed from Heloise to Abelard at the time when she was abbess at the Paraclete, and his answers to them.

Contributions to Women's Monastic Life

The Rule of Benedict, concerning monastic life, had lasted throughout the centuries and had been adequate for the lives of men, but women's bodies were different with physical needs that were not covered in the Rule. Eloise had an urgent need to reform monastic life to accommodate the new and expanding community of women.

Legacy

In the obituary created by her nuns, Heloise was called their "great mother." Her contributions to the rule guiding the lives of nuns both greatly needed and pioneering, set the standard for all nunneries and lasted until the French Revolution.

There seems to be some dissent as to her actual resting place.

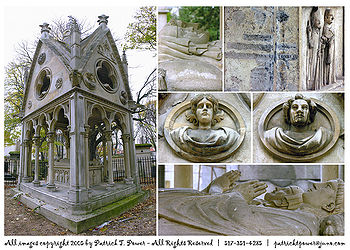

The Oratory of the Paraclete claims she and Abélard are buried on their site and that what exists in Père-Lachaise is merely a monument. According to the Père-Lachaise Cemetery, the remains of both lovers were transferred from the Oratory in the early 19th century and reburied in the famous crypt on their grounds. (illustration, left) There are still others who believe that while Abélard is buried in the crypt at Père-Lachaise, Heloïse's remains are elsewhere.

The love story of Abelard and Heloise inspired the poem "The Convent Threshold" by the Victorian English poet Christina Rossetti.

Howard Brenton's play In Extremis: The Story of Abelard and Heloise premiered at Shakespeare's Globe in 2006.

In the novel The Romantic by Barbara Gowdy the two central characters take their names from Heloise and Abelard (Louise and Abelard in the novel).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burge, James. Heloise & Abelard: A New Biography (Plus). HarpersSanFrancisco, 2006. ISBN 978-0060816131

- Clanchy, Michael, Betty Radice, trans. The Letters of Abelard and Heloise. Penguin Classics; Revised edition, 2004. ISBN 978-0140448993

- Mews, Contant J., Neville Chiavaroli, trans. The Lost Love Letters of Heloise and Abelard: Perceptions of Dialog in Twelfth-Century France (The New Middle Ages). Palgrave Macmillan; new ed. 2001. ISBN 978-0312239411

- Wheeler, Prof. Bonnie. Medieval Heroines in History and Legend. The Teaching Company, 2002. ISBN 1-56585-523-X

External links

- Abelard and Heloise from In Our Time (BBC Radio 4)

- The Letters of Abelard and Heloise

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.