Difference between revisions of "Consumption tax" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 176: | Line 176: | ||

*Burman, Len and William Gale. 2005. [http://www.brookings.edu/interviews/2005/0303taxes_gale.aspx The Pros and Cons of a Consumption Tax] Brookings interview. Retrieved May 20, 2009. | *Burman, Len and William Gale. 2005. [http://www.brookings.edu/interviews/2005/0303taxes_gale.aspx The Pros and Cons of a Consumption Tax] Brookings interview. Retrieved May 20, 2009. | ||

*Ehrbar, Al. 2008. [http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/ConsumptionTax.html Consumption Tax], ''The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics'', Library of Economics and Liberty. Retrieved April 30, 2009. | *Ehrbar, Al. 2008. [http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/ConsumptionTax.html Consumption Tax], ''The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics'', Library of Economics and Liberty. Retrieved April 30, 2009. | ||

| + | *Federalist paper No. 21 [http://www.conservativetruth.org/library/fed21.html Federalist Paper No. 21] | ||

*Greenspan, Alan. 2005. [http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,149298,00.html Consumption Tax Could Help Economy], Fox News, March 03, 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2009. | *Greenspan, Alan. 2005. [http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,149298,00.html Consumption Tax Could Help Economy], Fox News, March 03, 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2009. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*Gale, William G. , “The Pros and Cons of a Consumption Tax” , Brookings, April 25, 2009, | *Gale, William G. , “The Pros and Cons of a Consumption Tax” , Brookings, April 25, 2009, | ||

*Gourdeau, Claire, History of Consumption Taxes and Income Tax, Revenu Quebec, Gouvernement du Québec, 2002 | *Gourdeau, Claire, History of Consumption Taxes and Income Tax, Revenu Quebec, Gouvernement du Québec, 2002 | ||

*Hall, Robert E. and Alvin Rabushka, The Flat Tax, Hoover Institution, http://www.hoover.org/publications/books/3602666.html | *Hall, Robert E. and Alvin Rabushka, The Flat Tax, Hoover Institution, http://www.hoover.org/publications/books/3602666.html | ||

*Metcalf,Gilbert E.,"The National Sales Tax: Who Bears the Burden?" [http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa-289.html | *Metcalf,Gilbert E.,"The National Sales Tax: Who Bears the Burden?" [http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa-289.html | ||

| + | *Opinion Journal. 2008. [http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121875570585042551.html America the Uncompetitive], ''The Wall Street J." | ||

*Rothbard,Murray N. "Review of A. Chafuen, Christians for Freedom: Late Scholastic Economics," International Philosophical Quarterly 28 (March 1988),pp. 112–14. | *Rothbard,Murray N. "Review of A. Chafuen, Christians for Freedom: Late Scholastic Economics," International Philosophical Quarterly 28 (March 1988),pp. 112–14. | ||

*Rothbard Murray N., Power and Market: Government and the Economy, 2nd ed., Kansas City: Sheed Andrews & McMeel, 1977, pp. 120–21 | *Rothbard Murray N., Power and Market: Government and the Economy, 2nd ed., Kansas City: Sheed Andrews & McMeel, 1977, pp. 120–21 | ||

Revision as of 15:51, 25 May 2009

| Taxation |

|

|

|

| Types of Tax |

|---|

| Ad valorem tax · Consumption tax Corporate tax · Excise Gift tax · Income tax Inheritance tax · Land value tax Luxury tax · Poll tax Property tax · Sales tax Tariff · Value added tax |

| Tax incidence |

| Flat tax · Progressive tax Regressive tax · Tax haven Tax rate |

A consumption tax is a tax on spending on goods and services. The term refers to a system with a tax base of consumption. It usually takes the form of an indirect tax, such as a sales tax or value added tax. However it can also be structured as a form of direct, personal taxation: as an income tax that excludes investments and savings.

Since consumption taxes are argued to be inherently regressive on income, some current proposals make adjustments to decrease these effects. Using exemptions, graduated rates, deductions or rebates, a consumption tax can be made less regressive or progressive, while allowing savings to accumulate tax-free.

Definition

Consumption tax refers to a system with a tax base of spending or consumption. It is a tax charged to purchasers of goods and services. It usually takes the form of an indirect tax, such as a sales tax or value added tax.

A consumption tax essentially taxes people when they spend money. Under the income tax you're fundamentally taxed when you earn money or when you get interest, dividends, capital gains, and so on. With a consumption tax that wouldn't happen, you would be taxed essentially when you actually spent the money at the store. ... Under a consumption tax you'd actually pay tax on money you borrowed at the same time. So you wouldn't be taxed on your interest, dividends and capital gains, but you wouldn't be allowed a deduction for interest expense (Burman and Gale, 2005).

However it can also be structured as a form of direct, personal taxation: as an income tax that excludes investments and savings (Hall and Rabushka 1996, 281-320). This type of direct consumption tax is sometimes called an "expenditure tax," a "cash-flow tax," or a "consumed-income tax," and so forth.

Origins

The Emperor Augustus (27 B.C.E.) introduced an excise tax on goods, including slaves, sold in the public markets of Rome. The salt tax or gabelle, dates back to the start of the Roman period, that is, to the 8th century B.C.E. (Gourdeau 2002 ). Upon the arrival of the first European explorers, such as Christopher Columbus in 1492 and Jacques Cartier in 1534, North America was populated by Amerindian nations that had their own "taxation" system. Certain Native groups that served as intermediaries in the fur trade claimed a toll or a tax in kind when they conveyed pelt bales from one place to another. The Algonquins on the Ottawa River, for example, collected a percentage on furs, cornmeal, sunflower oil and medicinal herbs, in exchange for which they allowed travellers to portage in peace around the rapids (Gourdeau 2002 ).

In 17th century Canada, To have wheat ground at the mill, a habitant paid the seigneur every 14th bushel of grain to amortize the cost of the building and pay the miller's salary or wages. Similarly, a habitant was required to give every 14th fish to the seigneur in exchange for permission to fish the waters bordering the habitant's land grant and, when New France was turned over to England under the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the primary source of revenue for Lower Canada (Québec) was customs and excise duties on manufactured goods, wine, spirits and tobacco. (Gourdeau 2002 ).

Similar development of consumption taxes had been working ever since Christopher Columbus ( as mentioned above ) in North America and its French colonies.Thus, throughout most of American history, taxes were levied principally on consumption. Alexander Hamilton, one of the two chief authors of the anonymous Federalist Papers, favored consumption taxes in part because they are harder to raise to confiscatory levels than incomes taxes. In the Federalist Papers (No. 21), Hamilton wrote:

“…..It is a signal advantage of taxes on articles of consumption that they contain in their own nature a security against excess. They prescribe their own limit, which cannot be exceeded without defeating the end proposed—that is, an extension of the revenue. When applied to this object, the saying is as just as it is witty that, "in political arithmetic, two and two do not always make four." If duties are too high, they lessen the consumption; the collection is eluded; and the product to the treasury is not so great as when they are confined within proper and moderate bounds. This forms a complete barrier against any material oppression of the citizens by taxes of this class, and is itself a natural limitation of the power of imposing them…..” ( Federalist Paper No. 21 )

EXAMPLE: One of the first detailed analyses of a consumption tax was developed in 1974 by William Andrews ( Andrews 1974.) Under this proposal, people would only be taxed on what they consume, while their savings would be left untouched by taxation. In his article, Andrews also explains the power of deferral, and how the current income tax method taxes both income and savings. For example, Andrews offers the treatment of retirement income under the current tax system. If, in the absence of income taxes, $1 of savings is put aside for retirement at 9% compound interest, this will grow into $8 after 24 years. Under our current system, assuming a 33% tax rate, a person who earns $1 will only have $0.67 to invest after taxes. This person can only invest at an effective rate of 6%, since the rest of the yield is paid in taxes. After 24 years, this person is left with $2.67. But if, like in an Individual Retirement Account (IRA), this person can defer taxation on these savings, he will have $8 after 24 years, taxed only once at 33%, leaving $5.33 to spend on her retirement.

This is the primary concept of the consumption tax- the power of deferral. Even though the person in the above example is taxed at 33%, just like his colleagues, deferring that tax left him with twice the amount of money to spend in retirement. Had he not saved that dollar, he would have been taxed, leaving $0.67 to spend immediately on whatever he wanted. Harnessing the power of deferral is the most important concept behind a consumption tax.

NOTE: The example actually belong into the chapter “Consumption vs. Income tax” and will be discussed in greater details there. Timing the taxation in this way is the most important and makes more sense if the state wants increase the savings and investments. If this same person is taxed on the dollar he earns, but is never taxed again, the $0.67 he invests will grow to $5.33 in 24 years. The inflation ( after 24 years of inflated purchasing power ) is obviously an issue here. But the most important issue is to move the tax from income to consumption. Then, you are raising the relative burden on low savers, which are low and moderate income households, so almost any revenue neutral shift from the income tax to a consumption tax will be regressive in that manner ( Burman, Gale 2005).

Economics of Consumption Tax

Former senior editor of Fortune Magazine Al Ehrbar notes that proponents of a consumption tax argue its superiority to the income tax based on an economic principle called "temporal neutrality" (Ehrbar 2008).

He observes that a tax is "neutral" if it does not "alter spending habits or behavior patterns and thus does not distort the allocation of resources."

In other words, taxing apples but not oranges will cause apple consumption to decrease and orange consumption to increase. The temporal neutrality of a consumption tax, however, is that consumption itself is taxed, so it is irrelevant what good or service is being consumed in terms of allocation of resources. The only possible effect on neutrality is between consumption and savings. Taxing only consumption should, in theory, cause an increase in savings (Andrews 2005). William Gale, Co-director of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, offers a simplified way to understand a consumption tax: Assume that our current tax system remains the same, but remove limitations to contributing to and removing funds from a traditional Individual Retirement Account (IRA). Thus, a person would essentially have a bank account where they could place tax-free earnings at any time, but unsaved (or consumed) withdrawals would be subject to taxation. Having an unrestricted IRA under the current system would approximate a consumption tax at the federal level.

Many economists and tax experts favor consumption taxes over income taxes for economic growth (Regnier 2005; Greenspan 2005; Opinion Journal 2008).

Consumption taxes are neutral with respect to investment (Andrews 2005; Greenspan 2005). Depending on implementation (such as treatment of depreciation) and circumstances, income taxes either favor or disfavor investment. (On the whole, the US system is thought to disfavor investment (Andrews 2005). By not disfavoring investment, a consumption tax might increase the capital stock, productivity, and therefore increase the size of the economy (Andrews 2005; Auerbach 2005). Consumption more closely tracks long run average income (Auerbach 2005). An individual or family's income often varies dramatically from year to year. The sale of a home, a one time job bonus, and various other events can lead to temporary high income that will push a low or middle income person into a high tax bracket. On the other hand, a wealthy individual may be temporarily unemployed and will pay no taxes.

Taxing Income vs. Consumption

The basic difference between an income tax and a consumption tax is that a consumption tax only taxes money when it is spent. (Income taxes, by contrast, tax all the money you earn – including the amount you put away in your savings and the amount you get paid in interest.) Critics say the current system artificially increases the incentive to spend, while a consumption tax would encourage people to save and invest.

One of the chimeras of the tax economics claims that the VAT taxes, as practiced in Europe, might, eventually, do away with income tax. Here, again, the voice of reality says:

“….Some other variants are you could have a consumption tax where you just pay tax on your spending, a value added tax which they use in Europe and Japan; it's a variant of a sales tax and it's actually transparent to individuals, you don't have to, individuals don’t have to, file tax returns to pay that tax…… But an important distinction is that in Europe, the value added tax is a supplement to the income tax; it's not a replacement, so people still have to file income tax returns every year….."( Gale, 2009.)

The Income Tax

Income Tax places taxes on business profit and on the employee's wages which the business withholds from the employee in trust for the government. The VAT ( i.e. a consumption tax ) taxes business profit and total employee wages directly. Collection of employee wage taxes, in the case of Income Tax, is called "withholding" and in the VAT it's a direct "labor tax" on the business.

EXAMPLE: With the Income Tax, a $100 wage may have $10 tax withheld by the employer leaving $90 for the employee. With the VAT, the employee would be paid $90 and the employer would be subject to a $10 labor tax. Other than how it's perceived, there appears to be no difference between a Value Added Tax and a truly flat, non-discriminatory Income Tax that's collected at the source of income.

The case of the Excise tax

Orthodox neoclassical economics has long maintained that, from the point of view of the taxed themselves, an income tax is "better than" an excise tax on a particular form of consumption, since, in addition to the total revenue extracted, which is assumed to be the same in both cases, the excise tax weights the levy heavily against a particular consumer good.

EXAMPLE: An excise tax, say, on whiskey or on movie admissions, will intrude directly on no one's life and income, but only into the sales of the movie theater or liquor store. It is quite feasible that, in evaluating the "superiority" or "inferiority" of different modes of taxation, even the most determined imbiber or moviegoer would cheerfully pay far higher prices for whiskey or movies than neoclassical economists contemplate, in order to avoid the long arm of the IRS.[1]

But a new problem with excise tax appeared in the first decade of 21st century: a fast increasing price of gasoline and its excessive taxation. As gasoline is, in most developed countries, one of the necessities of life (just like the foodstuff) except that its price trend is several-fold steeper, one of the solution would, perhaps, be to nullify any excise tax on gasoline for “commuters” or introduce, for instance, a personal exemption.

Under this approach, which would differ substantially from a conventional value-added tax, workers would be considered to be "sellers" of labor services and would be subject to a value-added tax, but they could not take credits for value-added tax on their purchases of basic consumption goods, such as gasoline. Employers would be allowed a credit for the taxes "charged" by employees on their wages.

Argument for Consumption taxes

On the other side, the only coherent argument offered by advocates of consumption against income taxation is that of Irving Fisher, based on suggestions of John Stuart Mill. Fisher argued that, since the goal of all production is consumption, and since all capital goods are only way-stations on the way to consumption, the only genuine income is consumption spending. Based on consumption, rather than income, a national sales tax would not discriminate against saving the way the income tax does.

Accordingly, it may increase the level of private saving and generate a corresponding increase in capital formation and economic growth. A broad-based sales tax would almost certainly distort economic choices less than the income tax does. In contrast to the income tax, it would not discourage capital-intensive methods of production.

The conclusion is quickly drawn that therefore "...only consumption income, not what is generally called "income," should be subject to tax..." ( Rothbard, 1977, pp. 98–100.)

Concerns

Impact on government

In the earlier example analyzed by Andrews, the equation for the government is the opposite as it is for the taxpayer. Without the IRA tax benefits, the government collects $5.33 from the $1 saved over 24 years, but if the government gives the tax benefits, the government collects only $2.67 over the same period of time. The system is not free. Regardless of political philosophy, the fact remains that a government needs money to operate, and will have to get it from another source. The upside of the consumption tax is that, because it promotes savings, the tax will encourage capital formation, which will increase productivity and economic activity (Andrews 2005; Auerbach 2005). Secondly, the tax base will be larger because all consumption will be taxed.

Regressive nature

Some critics argue that sales and consumption taxes can shift the tax burden to the less well off. The ratio of tax obligation shrinks as wealth grows because the wealthy spend proportionally less of their income on consumables ( Metcalf.) Setting aside the question of rebates, a working class individual who must spend all income, will find his expenditures and therefore his income base taxable at 100%, whereas wealthy individuals who save or invest a portion of their income will only be taxed on the remaining income. This argument assumes that savings or investment is never taxed at a later point when consumed (tax-deferred).

One such concern was voiced in 2009 by an eminent U.S. tax expert:

“…. In theory you can set up a consumption tax to have any group of households pay it. In the real world, every consumption tax out there is going to hit low and middle income households to a greater extent than the income tax does. For two reasons: One is that, well, the main reason is that low and middle income households consume more of their income than high income households do. Another way of saying that is high income households save more of their income than low income households do..."( Gale, 2009 ).

“…..So if you move the tax from income to consumption, you're raising the relative burden on low savers, which are low and moderate income households, so almost any revenue neutral shift from the income tax to a consumption tax will be regressive in that manner. There are ways, there are conceptual ways to do it that doesn't add burdens to low and middle income households, but I don't think that they would actually happen…."( Gale, 2009. )

Practical considerations

Many proposed consumption taxes share some features with the current income tax systems. Under these proposals, taxpayers would be given exemptions and a standard deduction in order to ensure that the poor do not pay any tax. In a completely pure consumption tax, other deductions would not be permitted, because all savings would be deductible (Andrews 2005).

A consumption tax could also eliminate the concept of basis when computing the value of investments. All income that is put in investments (such as property, stocks, savings accounts) is tax-free. As the asset grows in value, it is not taxed. Only when the proceeds from the asset are spent is any tax imposed. This is in contrast with the current system where, if you buy land for $10,000 and sell it for $15,000, you have a taxable gain of $5,000. A consumption tax only taxes consumption, so if you sell one investment to buy another investment, no tax is imposed.

Lastly, a consumption tax could utilize progressive rates in order to maintain "fairness." The more someone spends on consumption, the more they will be taxed. Here, to maintain “real fairness” the different rate structure for necessities as opposed to luxury items might be introduced so that the “regressive” nature of consumption tax could be alleviated

The above benefits notwithstanding, there is till one small problem there. Some economists estimate that if you replaced all of our taxes with the sales ( consumption or VAT ) tax, the sales tax rate would be something like 60 percent, so you could just imagine getting into retirement and finding out the price of all the goods you're buying is now 60 percent higher than it was the day before. That would be like a 60 percent tax on all of the money that you had saved up over the course of your life ( Burman, Gale 2005 ).

Market vs. People decision on savings

The market, in short, knows all about the productive power of savings for the future, and allocates its expenditures accordingly. Yet even though people know that savings will yield them more future consumption, why don't they save all their current income?

Clearly, because of their time preferences for present as against future consumption. These time preferences govern people's allocation between present and future. Every individual, given his money "income"---defined in conventional terms---and his value scales, will allocate that income in the most desired proportion between consumption and investment. Any other allocation of such income, any different proportions, would therefore satisfy his wants and desires to a lesser extent and lower his position on his value scale.

It is therefore incorrect to say that an income tax levies an extra burden on savings and investment; it penalizes an individual's entire standard of living, present and future. An income tax does not penalize saving per se any more than it penalizes consumption.

"......Having challenged the merits of the goal of taxing only consumption and freeing savings from taxation, we can now proceed to deny the very possibility of achieving that goal, i.e., we maintain that a consumption tax will devolve, willy-nilly, into a tax on income and therefore on savings as well. In short, that even if, for the sake of argument, we should want to tax only consumption and not income, we should not be able to do so...." ( Rothbard, 1977 ).

EXAMPLE: See it on a simple example. Let us take a, seemingly straightforward, tax plan that would exempt saving and tax only consumption. Let us take Mr. Jones, who earns an annual income of $100,000. His time preferences lead him to spend 90 percent of his income on consumption, and save-and-invest the other 10 percent. On this assumption, he will spend $90,000 a year on consumption, and save-and-invest the other $10,000.

Let us assume now that the government levies a 20 percent tax on Jones's income, and that his time-preference schedule remains the same. The ratio of his consumption to savings will still be 90:10, and so, after-tax income now being $80,000, his consumption spending will be $72,000 and his saving-investment $8,000 per year.[2]

Suppose now that instead of an income tax, the government follows the Irving Fisher scheme and levies a 20 percent annual tax on Jones's consumption. Fisher maintained that such a tax would fall only on consumption, and not on Jones's savings. But this claim is incorrect, since Jones's entire savings-investment is based solely on the possibility of his future consumption, which will be taxed equally.

Since future consumption will be taxed, we assume, at the same rate as consumption at present, we cannot conclude that savings in the long run receives any tax exemption or special encouragement. There will therefore be no shift by Jones in favour of savings-and-investment due to a consumption tax.[3]

In sum, any payment of taxes to the government, whether they are consumption or income, necessarily reduces Jones's net income. Since his time preference schedule remains the same, Jones will therefore reduce his consumption and his savings proportionately. The consumption tax will be shifted by Jones until it becomes equivalent to a lower rate of tax on his own income.

If Jones still spends 90 percent of his net income on consumption, and 10 percent on savings-investment, his net income will be reduced by $15,000, instead of $20,000, and his consumption will now total $76,000, and his savings-investment $9,000. In other words, Jones's 20 percent consumption tax will become equivalent to a 15 percent tax on his income, and he will arrange his consumption-savings proportions accordingly.[4]

Graphical example

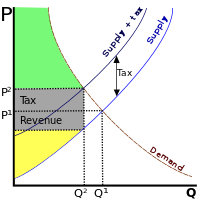

A VAT, like most taxes, distorts what would have happened without it. Because the price for someone rises, the quantity of goods traded decreases. Correspondingly, some people are worse off by more than the government is made better off by tax income . That is, more is lost due to supply and demand shifts than is gained in tax. This is known as a deadweight loss. The income lost by the economy is greater than the government's income; the tax is inefficient. The entire amount of the government's income (the tax revenue) may not be a deadweight drag, if the tax revenue is used for productive spending or has positive externalities - in other words, governments may do more than simply consume the tax income. While distortions occur, consumption taxes like VAT are often considered superior because they distort incentives to invest, save and work less than most other types of taxation - in other words, a VAT discourages consumption rather than production.

In the above diagram,

- Deadweight loss: the area of the triangle formed by the tax income box, the original supply curve, and the demand curve

- Government's tax income: the grey rectangle that says "tax"

- Total consumer surplus after the shift: the green area

- Total producer surplus after the shift: the yellow area

Notes

- ↑ It is particularly poignant, on or near any April 15, to contemplate the dictum of Father Navarrete, that "the only agreeable country is the one where no one is afraid of tax collectors" (Chafuen, Christians for Freedom, p. 73 ( Rothbard 1988: 112-114.) For a fuller treatment, and a discussion of who is being robbed by whom, see Rothbard 1977.

- ↑ We set aside the fact that, at the lower amount of money assets left to him, Jones's time preference rate, given his time preference schedule, will be higher, so that his consumption will be higher, and his savings lower, than we have assumed.

- ↑ In fact, per note [2], supra, there will be a shift in favour of consumption because a diminished amount of money will shift the taxpayer's time preference rate in the direction of consumption. Hence, paradoxically, a pure tax on consumption will and up taxing savings more than consumption (Rothbard, Power and Market, pp. 108–11.)

- ↑ lf net income is defined as gross income minus amount paid in taxes, and for Jones, consumption is 90 percent of net income, a 20 percent consumption tax on $100,000 income will be tantamount to a 15 percent tax on this income(see: ibid.) The basic formula for the net income is:

- N = G / ( 1+ t.c ),

References =

- Andrews, Edmund L. 2005. Fed's Chief Gives Consumption Tax Cautious Backing The New York Times, March 4, 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- Andrews, William D. “A Consumption-Type or Cash Flow Personal Income Tax,” 87, Harv. L. Rev. 1113, 1974.

- Auerbach, Alan J. 2005. A Consumption Tax, The Wall Street Journal, August 25, 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- Burman, Len and William Gale. 2005. The Pros and Cons of a Consumption Tax Brookings interview. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- Ehrbar, Al. 2008. Consumption Tax, The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, Library of Economics and Liberty. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- Federalist paper No. 21 Federalist Paper No. 21

- Greenspan, Alan. 2005. Consumption Tax Could Help Economy, Fox News, March 03, 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- Gale, William G. , “The Pros and Cons of a Consumption Tax” , Brookings, April 25, 2009,

- Gourdeau, Claire, History of Consumption Taxes and Income Tax, Revenu Quebec, Gouvernement du Québec, 2002

- Hall, Robert E. and Alvin Rabushka, The Flat Tax, Hoover Institution, http://www.hoover.org/publications/books/3602666.html

- Metcalf,Gilbert E.,"The National Sales Tax: Who Bears the Burden?" [http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa-289.html

- Opinion Journal. 2008. America the Uncompetitive, The Wall Street J."

- Rothbard,Murray N. "Review of A. Chafuen, Christians for Freedom: Late Scholastic Economics," International Philosophical Quarterly 28 (March 1988),pp. 112–14.

- Rothbard Murray N., Power and Market: Government and the Economy, 2nd ed., Kansas City: Sheed Andrews & McMeel, 1977, pp. 120–21

- Rothbard, Murray Toward a Reconstruction of Utility and Welfare Economics, J. of Libertanian Studies, 1977

- Regnier, Pat. 2005. Just how fair is the FairTax? Money Magazine, September 7, 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

Journal, August 15, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

External links

- OECD Center for Tax Policy and Administration

- Why do consumption taxes encourage saving?

- The Consumption Tax: Macroeconomic Effects- Edward Cremata

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.