Braille

| Braille | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type: | Alphabet (non-linear writing) | |

| Languages: | Several | |

| Created by | Louis Braille | |

| Time period: | 1821 to the present | |

| Parent writing systems: | Night writing Braille | |

| Unicode range: | U+2800 to U+28FF | |

| ISO 15924 code: | Brai | |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

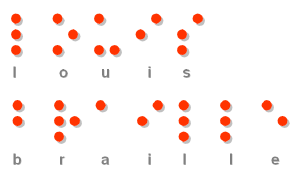

The braille system, devised in 1821 by Frenchman Louis Braille, is a method that is widely used by the blind to read and write. Each braille character or "cell" is made up of six dot positions, arranged in a rectangle containing two columns of three dots each. A dot may be raised at any of the six positions to form sixty-four combinations (including the combination in which no dots are raised). Braille has also been adapted for use in languages other than English.

Touch Reading in History

Braille was by no means humanity's first attempt at touch reading. In the fourteenth century, a blind Syrian professor named Zain-Din al Amidi improvised a method by which he identified his books and made notes. Although he was blind soon after birth, he led a studious life, interesting himself particularly in jurisprudence and foreign languages.

In 1517, Francisco Lucas of Saragossa used a set of thin wooden tablets with letters carved into them. In 1547, an Italian doctor named Girolamo Cardano suggested a system that somewhat resembled Braille. In 1676, an Italian Jesuit named Francesco Terzi created a type of cipher code based on dots enclosed in squares and other shapes. Terzi also advocated the use of a type of string alphabet, where knots were used to represent letters.

It was not until 1784 that the first school for the blind was founded by Frenchman Valentin Haüy, who taught the blind to read through the use of ordinary type printed in relief. This method was tedious, and the size of the books was incredibly cumbersome. In 1821, Haüy's school was visited by an ex-captain of artillery named Charles Barbier, who had recently developed a system of raised dots for use by soldiers who needed to communicate to each other during the night. Barbier's system was too intricate for use, but students at Haüy's school were interested in the concept, as it was easier to read than the embossed roman letter, and could be easily written using a stylus and metal flame. Barbier is generally credited with providing the inspiration for Braille.

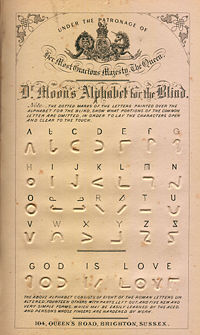

Numerous other forms of embossed type existed before the development of Braille. Many were based on the roman alphabet, including the popular Boston Line Letter, which used small angular letters with no capitals. All of the systems based on the roman alphabet were tediously difficult to master, and a new system was needed. Shorthand systems were developed, using straight and hooked lines. Most shorthand systems were also difficult to master, although works produced using them were shorter, and therefore cheaper and less bulky. The Moon system was a line system invented in 1847 by the English doctor William Moon. Moon, who became blind at age 21, devised a system of simplified roman letters and reduced the number of contractions used. The Moon system is still used by those who have difficulty reading braille and need a clearer, bolder type.[1]

Louis Braille

Louis Braille was born in 1809 near Paris. When Louis was three years old, he was playing in his father's shop and poked his eye on an awl. Infection set in, and despite medical care, Louis went completely blind. He was a bright child, and was sent to school by his parents, where he did remarkably well. At ten years old, he was sent to the Royal Institution for Blind Youth in Paris, a school founded by Valentin Haüy, where he learned to read raised print and developed a talent for both piano and organ.

When Charles Barbier visited the school with his phonetic system of raised dots and dashes, Louis immediately recognized the potential of such a system. By age 15, he had developed the basic system we know as braille. He went on to refine the braille system, and also devised methods for writing music.[2] It was not until after Braille's death that braille gained the worldwide popularity it has today. Initially developed in French, Braille has been adapted for use in most languages around the world.

How Braille Works

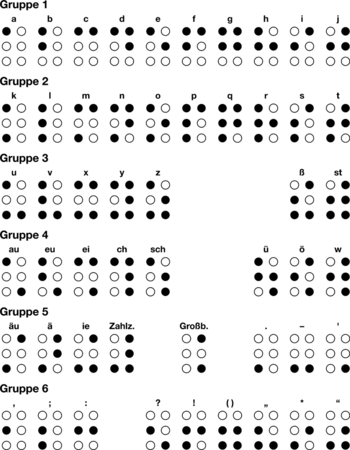

Today different braille codes (or code pages) are used to map character sets of different languages to the six bit cells. Different braille codes are also used for different uses like mathematics and music. However, because the six-dot Braille cell only offers 64 possible combinations, of which some are omitted because they feel the same (having the same dots pattern in a different position), many Braille characters have different meanings based on their context. Therefore, character mapping is not one-to-one.

In addition to simple encoding modern braille transcription uses contractions to increase reading speed.

The Braille cell

Braille generally consists of cells of 6 raised dots arranged in a grid of two dots horizontally by three dots vertically. The dots are conventionally numbered 1, 2, and 3 from the top of the leftward column and 4, 5, and 6 from the top of the rightward column.

The presence or absence of dots gives the coding for the symbol. Dot height is approximately 0.02 inches (0.5 mm); the horizontal and vertical spacing between dot centers within a braille cell is approximately 0.1 inches (2.5 mm); the blank space between dots on adjacent cells is approximately 0.15 inches (3.75 mm) horizontally and 0.2 inches (5.0 mm) vertically. A standard braille page is 11 inches by 11.5 inches and typically has a maximum of 40 to 43 braille cells per line and 25 lines.

Large Cell or "Jumbo" Braille is often used by those who have difficulty feeling standard Braille. The dot combinations are the same as those used in traditional Braille, but the spacing between dots and cells is somewhat increased. The dots themselves are the same size as dots in standard braille, but the added spacing makes them easier to feel.

Encoding

As originally conceived by Louis Braille, the first ten letters of the alphabet are formed from combinations of the top four dots. The next ten letters add the lower left dot (dot 3) to the previous ten symbols. Both bottom dots (3 and 6) are added to the next group of ten letters, although the letter "W" is an exception to this pattern. The French language did not make use of the letter "w" at the time Louis Braille devised his alphabet, and thus he had no need to encode the letter "w."

English braille uses twenty six symbols to represent the alphabet. Punctuation takes up ten characters, and the remaining combinations are used to represent contractions, or any special characters that may be required by a specific language

English braille codes the letters and punctuation, and some double letter signs and word signs directly, but capitalization and numbers are dealt with by using a prefix symbol. In practice, braille produced in the United Kingdom does not have capital letters.

There are specific braille codes for representing shorthand (produced on a machine which embosses a paper tape) and for representing mathematics (Nemeth Braille) and musical notation (braille music).

Grades of Braille

Many languages have two main grades of braille: Grade 1 and Grade 2. Grade one is used mainly by beginners, and spells each word out letter by letter. Grade 2 braille is the most commonly used form of braille, and uses various contractions to represent prefixes, suffixes, pronouns, conjunctions, prepositions, and other common groups of letters or words. Grade 2 braille makes reading and writing quicker and significantly less bulky. A number of languages have a Grade 3 braille, which is highly abridged and similar to shorthand. Grade 3 braille is more complex, requires a good command of language and a good memory, and is only used by a small minority of readers.[3]

Writing braille

Braille may be produced using a "slate" and a "stylus" in which each dot is created from the back of the page, writing in mirror image by hand. It may be produced mechanically on a braille typewriter or "Perkins Brailler," or by a braille embosser attached to a computer. Braille is also sometimes rendered using a refreshable braille display.

In some cases, braille has been extended to an eight dot code, particularly for special purposes, such as computer access. In 8 dot braille the additional dots are added at the bottom of the cell, giving a matrix 4 dots high by 2 dots wide. The additional dots are given the numbers 7 (for the lower-left dot) and 8 (for the lower-right dot). Six dot braille, however, remains the best form for general reading purposes.[4]

Braille transcription

Braille characters are much larger than their printed equivalents, and the standard 11" by 11.5" (28 cm × 30 cm) page has room for only 25 lines of 43 characters. To reduce space and increase reading speed, virtually all braille books are transcribed in Grade 2 Braille, using a system of contractions to reduce space and speed the process of reading. As with most human linguistic activities, Grade 2 Braille embodies a complex system of customs, styles, and practices. The Library of Congress's Instruction Manual for Braille Transcribing runs to nearly 200 pages. Braille transcription is skilled work, and braille transcribers need to pass certification tests.

The current series of Canadian banknotes have raised dots on the banknotes that indicate the denomination and can be easily identified by visually impaired people; this 'tactile feature' does not use standard braille but, instead, a system developed in consultation with blind and visually impaired Canadians after research indicated that not all potential users read braille.

Though braille is thought to be the main way blind people read and write, in Britain (for example) out of the reported 2 million visually impaired population, it is estimated that only around 15-20 thousand people use Braille. Younger people are turning to electronic text on computers instead; a more portable communication method that they can also use with their friends. A debate has started on how to make braille more attractive and for more teachers to be available to teach it.

In India there are instances where the parliament acts have been published in Braille too. For example 'The Right to Information Act'

Braille for other scripts

There are many extensions of Braille for additional letters with diacritics, such as ç, ô, é.

When braille is adapted to languages which do not use the Latin alphabet, the cells or "blocks" are generally assigned to the new alphabet according to how it is transliterated into the Latin alphabet, and the alphabetic order of the national script (and therefore the natural order of Latin braille) is disregarded. Such is the case with Russian, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, and Chinese. In Greek, for example, gamma is written as Latin g, despite the fact that it has the alphabetic position of c, and in Hebrew, bet, the second letter of the alphabet and cognate with the Latin letter b, is instead written v, as it is commonly pronounced.

Greater differences occur in Chinese braille. In the case of Mandarin Braille, which is based on Zhuyin rather than the Latin Pinyin alphabet, the traditional Latin braille values are used for initial consonants and the simple vowels. However, there are additional blocks for the tones, diphthongs, and vowel + consonant combinations. Cantonese Braille is also based on Latin braille for many of the initial consonants and simple vowels (based on romanizations of a century ago), but the blocks pull double duty, with different values depending on their position.

However, at least three adaptations of Braille have completely reassigned the Latin sound values of the blocks. These are, Japanese braille, Korean braille, and Tibetan braille. These modifications made Braille much more compatible with Japanese kana and Korean hangul, but meant that the Latin sound values could not be maintained.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Mellor, C. Michael. Louis Braille: A Touch of Genius March 2006. National Braille Press. ISBN 0939173700

- Miller, Susanna. Reading by Touch June 1997. Routledge. ISBN 041506838X

- Roberts, Helen. An introduction to Braille mathematics: Based on The Nemeth Braille code for mathematics and science notation 1972. ISBN 0844401900

External links

Organizations

- Braille Authority of North America

- Braille - American Foundation for the Blind

- Royal National Institute For The Blind

- Perkins School for the Blind

- National Braille Press - offers a free Braille alphabet card

Libraries

- The National Library for the Blind

- Libraries Australia - catalog of braille in 800+ Australian libraries

Learning

- Braille Bug - an educational site for kids, from the American Foundation for the Blind

- BRL: Braille Through Remote Learning

- On-line Braille Course of University of São Paulo

- Online Braille Generator

- Online Braille Translation

- A braille alphabet card

History

- How Braille Began—a detailed history of braille's origins and the people who supported and opposed the system.

- Robert B. Irwin's As I Saw It, 1955, gives a history of the "War of the Dots" that ultimately led to the adoption of the English form of the braille literary code in the United States and the demise of American braille and New York Point, its main competitors.

Documents

- English Braille: American Edition

- Library of Congress Instructional Manual for Braille Transcribing

- Unified (English) Braille Code (including information specific to British braille)

- Braille code for Russian and transliteration of Cyrillic

Legal

Language Specific Resources

Computer Resources

- Braille for various scripts

- Free Braille fonts

- Free Unicode Braille TTF font (supports all Braille scripts)

- Free Unicode fonts which include braille

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ "Reading by Touch Royal National Institute of Blind People. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Louis Braille" Duxbury Systems Inc. May 3, 2007. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Reading by Touch Royal National Institute of Blind People. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Louis Braille" Duxbury Systems Inc. May 3, 2007. Retrieved November 9, 2007.