Difference between revisions of "Aspasia" - New World Encyclopedia

(add ce template to hold) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Paid | + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | [[Image:394px-Aspasie_Pio-Clementino_Inv272.jpg|thumb|Marble herm in the [[Vatican Museums]] inscribed with Aspasia's name at the base. Discovered in 1777, this marble herm is a Roman copy of a fifth century | + | [[Image:394px-Aspasie_Pio-Clementino_Inv272.jpg|thumb|Marble herm in the [[Vatican Museums]] inscribed with Aspasia's name at the base. Discovered in 1777, this marble herm is a Roman copy of a fifth century B.C.E. original and may represent Aspasia's funerary stele.]] |

| − | '''Aspasia''' (c. 470 | + | '''Aspasia''' (c. 470 B.C.E. - 400 B.C.E.) [[Greek language|Greek]]: {{Polytonic|Ἀσπασία}}) was a woman rhetorician and philosopher in [[ancient Greece]], famous for her romantic involvement with the Athenian statesman [[Pericles]]. She was born in the city of Miletus in [[Asia Minor]], and around 450 B.C.E. traveled to [[Athens]], where she spent the rest of her life. She is thought to have exercised considerable influence on Pericles, both politically and philosophically. [[Plato]] suggested that she helped compose Pericles' famous ''Funeral Oratory,'' and that she trained Pericles and [[Socrates]] in oratory. After the death of Pericles she was allegedly involved with Lysicles, another Athenian statesman and general. She had a son with Pericles, Pericles the Younger, who was elected general and was executed after a naval disaster at the Battle of Arginusae. |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | Aspasia appears in the philosophical writings of [[Xenophon]], [[Aeschines Socraticus]], [[Plato]] | + | Aspasia appears in the philosophical writings of [[Xenophon]], [[Aeschines Socraticus]], [[Plato]] and [[Antisthenes]] and is regarded by modern scholars as an exceptional person who distinguished herself due to her political influence and intellectual charisma. Most of what is known about her comes from the comments of ancient philosophers and writers, some of whom were comic poets who wished to disparage Pericles, rather than from factual accounts. Scholars believe that most of the stories told about her are myths reflecting her status and influence. |

== Origin == | == Origin == | ||

| − | Aspasia was born around 470 | + | Aspasia was born around 470 B.C.E. in the [[Ionia|Ionian]] Greek colony of Miletus (in the modern Aydin Province, [[Turkey]]). Her father's name was Axiochus. She was a free woman, not a Carian prisoner-of-war turned slave as some ancient sources claim. She probably belonged to a wealthy and cultured family, because her parents provided her with an extensive education. |

| − | The circumstances that took her to Athens are not known. The discovery of a fourth-century grave inscription that mentions the names of Axiochus and Aspasius has led historian Peter J. Bicknell to attempt a reconstruction of Aspasia's family background and Athenian connections. His theory connects her to Alcibiades II of Scambonidae, who was ostracized from Athens in 460 | + | The circumstances that took her to Athens are not known. The discovery of a fourth-century grave inscription that mentions the names of Axiochus and Aspasius has led historian Peter J. Bicknell to attempt a reconstruction of Aspasia's family background and Athenian connections. His theory connects her to Alcibiades II of Scambonidae, who was ostracized from Athens in 460 B.C.E. and may have spent his exile in Miletus. Bicknell conjectures that, following his exile, the elder Alcibiades went to Miletus, where he married the daughter of a certain Axiochus. Alcibiades apparently returned to Athens with his new wife and her younger sister, Aspasia. Bicknell argues that the first child of this marriage was named Axiochus (uncle of the famous [[Alcibiades]]) and the second Aspasios. He also maintains that Pericles met Aspasia through his close connections with Alcibiades's household. |

== Life in Athens == | == Life in Athens == | ||

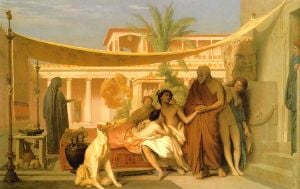

[[Image:AspasiaAlcibiades.jpg|thumb|left|Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904): Socrates seeking Alcibiades in the house of Aspasia, 1861]] | [[Image:AspasiaAlcibiades.jpg|thumb|left|Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904): Socrates seeking Alcibiades in the house of Aspasia, 1861]] | ||

{| class="toccolours" style="float: right; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | {| class="toccolours" style="float: right; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| − | | style="text-align: left;" |”And so Aspasia, as some say, was held in high | + | | style="text-align: left;" |”And so Aspasia, as some say, was held in high favor by Pericles because of her rare political wisdom. Socrates sometimes came to see her with his disciples, and his intimate friends brought their wives to her to hear her discourse, although she presided over a business that was any- thing but honest or even reputable, since she kept a house of young courtesans. And Aeschines says that Lysicles the sheep-dealer, a man of low birth and nature, came to be the first man at Athens by living with Aspasia after the death of Pericles. And in the “Menexenus” of Plato, even though the first part of it be written in a sportive vein, there is, at any rate, thus much of fact, that the woman had the reputation of associating with many Athenians as a teacher of rhetoric. However, the affection which Pericles had for Aspasia seems to have been rather of an amatory sort. For his own wife was near of kin to him, and had been wedded first to Hipponicus, to whom she bore Callias, surnamed the Rich; she bore also, as the wife of Pericles, Xanthippus and Paralus. Afterwards, since their married life was not agreeable, he legally bestowed her upon another man, with her own consent, and himself took Aspasia, and loved her exceedingly. Twice a day, as they say, on going out and on coming in from the market-place, he would salute her with a loving kiss. But in the comedies she is styled now the New Omphale, now Deianeira, and now Hera. Cratinus flatly called her a prostitute … So renowned and celebrated did Aspasia become, they say, that even Cyrus, the one who went to war with the Great King for the sovereignty of the Persians, gave the name of Aspasia to that one of his concubines whom he loved best, who before was called Milto. She was a Phocaean by birth, daughter of one Hermotimus, and, after Cyrus had fallen in battle, was carried captive to the King, and acquired the greatest influence with him. These things coming to my recollection as I write, it were perhaps unnatural to reject and pass them by." (Plutarch, ''Pericles,'' XXIV) |

|- | |- | ||

| style="text-align: left;" | From Aristophanes' comedic play, ''The Acharnians'' (523-533) | | style="text-align: left;" | From Aristophanes' comedic play, ''The Acharnians'' (523-533) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | According to the disputed statements of the ancient writers and some modern scholars, in Athens Aspasia became a ''hetaera.'' ''Hetaerae'' were professional entertainers of upper class men, as well as courtesans. | + | According to the disputed statements of the ancient writers and some modern scholars, in Athens Aspasia became a ''hetaera.'' ''Hetaerae'' were professional entertainers of upper class men, as well as courtesans. They differed from most Athenian women in being well educated, having independence, and paying taxes. According to [[Plutarch]], Aspasia was compared to the famous Thargelia, another renowned Ionian ''hetaera'' of ancient times. |

| − | Being a foreigner and possibly a ''hetaera'' | + | Being a foreigner and possibly a ''hetaera,'' Aspasia was freed from the legal restraints that traditionally confined married women to their homes and could therefore participate in the public life of the city. After the statesman [[Pericles]] divorced his first wife (c. 445 B.C.E.), Aspasia began to live with him, although her marital status remains disputed as she was not a citizen of Athens. Their son, Pericles the Younger, was probably born before 440 B.C.E. because it is reported that she later bore another child to Lysicles, around 428 B.C.E.. |

| − | Aspasia was noted for her ability as a conversationalist and adviser rather than merely an object of physical beauty. | + | Aspasia was noted for her ability as a conversationalist and adviser rather than merely an object of physical beauty. According to [[Plutarch]], their house became an intellectual centre in [[Athens]], attracting the most prominent writers and thinkers, including the philosopher [[Socrates]]. The biographer writes that Athenians used to bring their wives to hear her discourses. |

== Personal and Judicial Attacks == | == Personal and Judicial Attacks == | ||

| − | Aspasia’s relationship with [[Pericles]] and her consequent political influence aroused public sentiment against her. In 440 | + | Aspasia’s relationship with [[Pericles]] and her consequent political influence aroused public sentiment against her. In 440 B.C.E., Samos was at war with Miletus over Priene, an ancient city of Ionia in the foot-hills of Mycale. The Milesians came to Athens to plead their case against the Samians, but when the Athenians ordered the two sides to stop fighting and submit the case to arbitration at Athens, the Samians refused. In response, Pericles passed a decree dispatching an expedition to Samos. The campaign proved to be difficult and the Athenians endured heavy casualties before Samos was defeated. According to [[Plutarch]], it was thought that Aspasia, who came from Miletus, was responsible for the Samian War, and that Pericles had decided against and attacked Samos to gratify her. |

| − | Plutarch reports that before the outbreak of the [[Peloponnesian War]] (431 | + | Plutarch reports that before the outbreak of the [[Peloponnesian War]] (431 B.C.E. - 404 B.C.E.), Pericles, some of his closest associates and Aspasia faced a series of personal and legal attacks. Aspasia, in particular, was accused of corrupting the women of Athens in order to satisfy Pericles' desires. According to Plutarch, she was put on trial for impiety, with the comic poet Hermippus as prosecutor. All these accusations were probably unproven slanders, but the experience was bitter for the Athenian leader. Although Aspasia was acquitted thanks to a rare emotional outburst of Pericles, his friend, Phidias, died in prison. Another friend of his, Anaxagoras, was attacked by the Ecclesia (the Athenian Assembly) for his religious beliefs. It is possible that Plutarch’s account of Aspasia's trial and acqittal was a historical invention based on earlier slanders and ribald comedies. |

| − | In his play, ''The Acharnians,'' [[Aristophanes]] blames Aspasia for the [[Peloponnesian War]], claiming that the Megarian decree of Pericles, which excluded Megara from trade with Athens or its allies, was retaliation for prostitutes being kidnapped from the house of Aspasia by Megarians. | + | In his play, ''The Acharnians,'' [[Aristophanes]] blames Aspasia for the [[Peloponnesian War]], claiming that the Megarian decree of Pericles, which excluded Megara from trade with Athens or its allies, was retaliation for prostitutes being kidnapped from the house of Aspasia by Megarians. Plutarch also reports the slurs of other comic poets, such as Eupolis and Cratinus. [[Douris]] appears to have promoted the view that Aspasia instigated both the Samian and Peloponnesian Wars. Aspasia was labeled the "New Omphale," "Deianira," "Hera" and "Helen." (Omphale and Deianira were respectively the Lydian queen who owned [[Heracles]] as a slave for a year and his long-suffering wife. The comedians parodied Pericles for resembling a Heracles under the control of an Omphale-like Aspasia.) Further attacks on Pericles' relationship with Aspasia are reported by [[Athenaeus]]. Pericles's own son, [[Xanthippus]], who had political ambitions, did not hesitate to slander his father over his domestic affairs. |

== Later Years and Death == | == Later Years and Death == | ||

| − | + | ||

{| class="toccolours" style="float: right; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | {| class="toccolours" style="float: right; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| style="text-align: left;" | "Thus far the evil was not serious and we were the only sufferers. But now some young drunkards go to Megara and carry off the courtesan Simaetha; the Megarians, hurt to the quick, run off in turn with two harlots of the house of Aspasia; and so for three whores Greece is set ablaze. Then Pericles, aflame with ire on his Olympian height, let loose the lightning, caused the thunder to roll, upset Greece and passed an edict, which ran like the song, That the Megarians be banished both from our land and from our markets and from the sea and from the continent." | | style="text-align: left;" | "Thus far the evil was not serious and we were the only sufferers. But now some young drunkards go to Megara and carry off the courtesan Simaetha; the Megarians, hurt to the quick, run off in turn with two harlots of the house of Aspasia; and so for three whores Greece is set ablaze. Then Pericles, aflame with ire on his Olympian height, let loose the lightning, caused the thunder to roll, upset Greece and passed an edict, which ran like the song, That the Megarians be banished both from our land and from our markets and from the sea and from the continent." | ||

|- | |- | ||

| style="text-align: left;" | From Aristophanes' comedic play, ''The Acharnians'' (523-533) | | style="text-align: left;" | From Aristophanes' comedic play, ''The Acharnians'' (523-533) | ||

| − | |}The return of soldiers from the battle front brought the plague to Athens. | + | |}The return of soldiers from the battle front brought the plague to Athens. In 429 B.C.E., Pericles witnessed the death of his sister and of both his legitimate sons from his first wife, Xanthippus and his beloved Paralus, from the disease. With his morale undermined, he burst into tears, and not even Aspasia could console him. Just before his death, the Athenians allowed a change in the citizenship law that made his half-Athenian son with Aspasia, Pericles the Younger, a citizen and legitimate heir. Pericles himself had proposed the law in 451 B.C.E. confining Athenian citizenship to those of Athenian parentage on both sides, to prevent aristocratic families from forming alliances with other cities. Pericles died in the autumn of 429 B.C.E.. |

| + | |||

| + | Plutarch cites a dialogue by [[Aeschines Socraticus]] (now lost), to the effect that after Pericles's death Aspasia lived with Lysicles, an Athenian general and democratic leader, with whom she had another son; and that she helped him rise to a high position in Athens. Lysicles was killed in action in 428 B.C.E., and after his death there is no further record of Aspasia. The date given by most historians for her death (c. 401 B.C.E..E. - 400 B.C.E.) is based on the assessment that Aspasia died before the execution of Socrates in 399 B.C.E., a chronology which is implied in the structure of Aeschines' ''Aspasia.'' | ||

| − | |||

==References in Philosophical Works== | ==References in Philosophical Works== | ||

| − | ===Ancient | + | |

| + | ===Ancient philosophical works=== | ||

{| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| style="text-align: left;" |"Now, since it is thought that he proceeded thus against the Samians to gratify Aspasia, this may be a fitting place to raise the query what great art or power this woman had, that she managed as she pleased the foremost men of the state, and afforded the philosophers occasion to discuss her in exalted terms and at great length." | | style="text-align: left;" |"Now, since it is thought that he proceeded thus against the Samians to gratify Aspasia, this may be a fitting place to raise the query what great art or power this woman had, that she managed as she pleased the foremost men of the state, and afforded the philosophers occasion to discuss her in exalted terms and at great length." | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: left;" | '''''Plutarch''', ''Pericles'' | + | | style="text-align: left;" | '''''Plutarch''', ''Pericles,'' XXIV |

| − | |}Aspasia appears in the philosophical writings of [[Plato]], [[Xenophon]], [[Aeschines Socraticus]] and [[Antisthenes]]. Some scholars suggest that Plato was impressed by her intelligence and wit and based his character Diotima in ''Symposium'' on her, while others believe that Diotima was in fact a historical figure. | + | |}Aspasia appears in the philosophical writings of [[Plato]], [[Xenophon]], [[Aeschines Socraticus]] and [[Antisthenes]]. Some scholars suggest that Plato was impressed by her intelligence and wit and based his character Diotima in ''Symposium'' on her, while others believe that Diotima was in fact a historical figure. According to Charles Kahn, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, Diotima is in many respects Plato's response to Aeschines' Aspasia. |

| − | In ''Menexenus,'' Plato satirizes Aspasia's relationship with Pericles, and quotes [[Socrates]] as claiming that she trained many orators. Socrates' intention is to cast aspersions on Pericles' rhetorical abilities, claiming that, since the Athenian statesman was educated by Aspasia, he would be superior in [[logic|rhetoric]] to someone educated by Antiphon. | + | In ''Menexenus,'' Plato satirizes Aspasia's relationship with Pericles, and quotes [[Socrates]] as claiming that she trained many orators. Socrates' intention is to cast aspersions on Pericles' rhetorical abilities, claiming that, since the Athenian statesman was educated by Aspasia, he would be superior in [[logic|rhetoric]] to someone educated by Antiphon. He also attributes authorship of Pericles’ ''Funeral Oration'' to Aspasia and attacks his contemporaries' veneration of Pericles. Kahn maintains that Plato has taken the idea of Aspasia as teacher of rhetoric for Pericles and Socrates from Aeschines. |

| − | [[Xenophon]] mentions Aspasia twice in his Socratic writings | + | [[Xenophon]] mentions Aspasia twice in his Socratic writings: in ''Memorabilia'' and in ''Oeconomicus.'' In both cases her advice is recommended to Critobulus by Socrates. In ''Memorabilia'' Socrates quotes Aspasia as saying that the matchmaker should report truthfully on the good characteristics of the man. In ''Oeconomicus'' Socrates defers to Aspasia as being the one more knowledgeable about household management and the economic partnership between husband and wife. |

| − | [[Image:Illus0362.jpg|thumb|Painting of Hector Leroux (1682 - 1740), which portrays Pericles and Aspasia, admiring the gigantic statue of Athena in Phidias' studio.]] | + | [[Image:Illus0362.jpg|thumb|Painting of Hector Leroux (1682 - 1740), which portrays Pericles and Aspasia, admiring the gigantic statue of Athena in Phidias' studio.]] |

| − | [[Aeschines Socraticus]] and [[Antisthenes]] each named a Socratic dialogue after Aspasia (though neither survives except in fragments). Our major sources for Aeschines Socraticus' ''Aspasia'' are Athenaeus, [[Plutarch]], and [[Cicero]]. In the dialogue, Socrates recommends that Callias send his son Hipponicus to Aspasia for instructions. When Callias recoils at the notion of a female teacher, Socrates notes that Aspasia had favorably influenced Pericles and, after his death, Lysicles. In a section of the dialogue, preserved in Latin by Cicero, Aspasia figures as a "female Socrates," counseling first Xenophon's wife and then Xenophon (not the famous historian Xenophon) himself | + | [[Aeschines Socraticus]] and [[Antisthenes]] each named a Socratic dialogue after Aspasia (though neither survives except in fragments). Our major sources for Aeschines Socraticus' ''Aspasia'' are Athenaeus, [[Plutarch]], and [[Cicero]]. In the dialogue, Socrates recommends that Callias send his son Hipponicus to Aspasia for instructions. When Callias recoils at the notion of a female teacher, Socrates notes that Aspasia had favorably influenced Pericles and, after his death, Lysicles. In a section of the dialogue, preserved in Latin by Cicero, Aspasia figures as a "female Socrates," counseling first Xenophon's wife and then Xenophon (not the famous historian Xenophon) himself about acquiring virtue through self-knowledge. Aeschines presents Aspasia as a teacher and inspirer of excellence, connecting these virtues with her status as hetaira. |

| − | Of Antisthenes' ''Aspasia'' only two or three quotations are extant. This dialogue contains both | + | Of Antisthenes' ''Aspasia'' only two or three quotations are extant. This dialogue contains both aspersions and anecdotes about Pericles. Antisthenes appears to have attacked not only Aspasia, but the entire family of Pericles, including his sons. The philosopher believes that the great statesman chose the life of pleasure over virtue, presenting Aspasia as the personification of a life of self-indulgence. |

{| class="toccolours" style="float: right; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | {| class="toccolours" style="float: right; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| − | | style="text-align: left;" |"All argumentation, then, is to be carried on either by induction or by deduction. Induction is a form of argument which leads the person with whom one is arguing to give assent to certain undisputed facts; through this assent it wins his approval of a doubtful proposition because this resembles the facts to which he has assented. For instance, in a | + | | style="text-align: left;" |"All argumentation, then, is to be carried on either by induction or by deduction. Induction is a form of argument which leads the person with whom one is arguing to give assent to certain undisputed facts; through this assent it wins his approval of a doubtful proposition because this resembles the facts to which he has assented. For instance, in a dialogue by Aeschines Socraticus Socrates reveals that Aspasia reasoned thus with Xenophon's wife and with Xenophon himself: "Please tell me, madam, if your neighbour had a better gold ornament than you have, would you prefer that one or your own?" "That one," she replied. "Now, if she had dresses and other feminine finery more expensive than you have, would you prefer yours or hers?" "Hers, of course," she replied. "Well now, if she had a better husband than you have, would you prefer your husband or hers?" At this the woman blushed. But Aspasia then began to speak to Xenophon. "I wish you would tell me, Xenophon," she said, "if your neighbour had a better horse than yours, would you prefer your horse or his?" "His" was his answer. "And if he had a better farm than you have, which farm would your prefer to have?" The better farm, naturally," he said. "Now if he had a better wife than you have, would you prefer yours or his?" And at this Xenophon, too, himself was silent. Then Aspasia: "Since both of you have failed to tell me the only thing I wished to hear, I myself will tell you what you both are thinking. That is, you, madam, wish to have the best husband, and you, Xenophon, desire above all things to have the finest wife. Therefore, unless you can contrive that there be no better man or finer woman on earth you will certainly always be in dire want of what you consider best, namely, that you be the husband of the very best of wives, and that she be wedded to the very best of men."'' (Cicero, ''Institutio Oratoria,'' V.11. 27-29) |

|- | |- | ||

| style="text-align: left;" | From Aristophanes' comedic play, ''The Acharnians'' (523-533) | | style="text-align: left;" | From Aristophanes' comedic play, ''The Acharnians'' (523-533) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | ===Modern | + | ===Modern literature=== |

[[Image:Aspasia painting.jpg|thumb|left|Painting of Marie Bouliard, which potrays Aspasia, 1794]] | [[Image:Aspasia painting.jpg|thumb|left|Painting of Marie Bouliard, which potrays Aspasia, 1794]] | ||

| − | Aspasia appears in several significant works of modern literature. Her romantic attachment with Pericles particularly inspired the romanticists of the nineteenth century and the historical novelists of the twentieth century. In 1835 [[Lydia Child]], an American [[abolitionist]], novelist, and journalist published ''Philothea'' | + | Aspasia appears in several significant works of modern literature. Her romantic attachment with Pericles particularly inspired the romanticists of the nineteenth century and the historical novelists of the twentieth century. In 1835 [[Lydia Child]], an American [[abolitionist]], novelist, and journalist published ''Philothea,'' a classical romance set in the days of Pericles and Aspasia. This book is regarded as her most successful and elaborate because the female characters, and especially Aspasia, are portrayed with beauty and delicacy. In 1836 Walter Savage Landor, an English writer and poet, published ''Pericles and Aspasia,'' a rendering of classical Athens through a series of imaginary letters, which contain numerous poems. The letters are frequently unfaithful to actual history but attempt to capture the spirit of the Age of Pericles. In 1876 Robert Hamerling published his novel ''Aspasia,'' a book about the manners and morals of the Age of Pericles and a work of cultural and historical interest. Giacomo Leopardi, an Italian poet influenced by the movement of romanticism, published a group of five poems known as the ''circle of Aspasia.'' The poems were inspired by his painful experience of desperate and unrequited love for a woman named Fanny Targioni Tozzetti, whom he called “Aspasia” after the companion of Pericles. |

| − | In 1918 novelist and playwright George Cram Cook produced his first full-length play, ''The Athenian Women,'' portraying Aspasia leading a strike for peace. | + | In 1918 novelist and playwright George Cram Cook produced his first full-length play, ''The Athenian Women,'' portraying Aspasia leading a strike for peace. American writer Gertrude Atherton in ''The Immortal Marriage'' (1927) recreates the story of Pericles and Aspasia, and illustrates the period of the Samian War, the Peloponnesian War and the plague. |

== Significance == | == Significance == | ||

| − | Historically, Aspasia's name is closely associated with Pericles's glory and fame. Her reputation as a philosopher and rhetorician is mostly anecdotal, as are the details about her personal life. | + | Historically, Aspasia's name is closely associated with Pericles's glory and fame. Her reputation as a philosopher and rhetorician is mostly anecdotal, as are the details about her personal life. Some scholars suggest that Plato derived his portrayal of Aspasia as an intellectual from earlier Greek comedies, and that his remarks that she trained Pericles and Socrates in oratory should not be construed as historical fact. Whether the stories about Aspasia are fact or legend, no other woman achieved the same stature in ancient Greek history or literature. She is regarded by modern scholars as an exceptional person who distinguished herself due to her political influence and intellectual charisma. |

{| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| style="text-align: left;" | "Next I have to depict Wisdom; and here I shall have occasion for many models, most of them ancient; one comes, like the lady herself, from Ionia. The artists shall be Aeschines and Socrates his master, most realistic of painters, for their heart was in their work. We could choose no better model of wisdom than Milesian Aspasia, the admired of the admirable 'Olympian'; her political knowledge and insight, her shrewdness and penetration, shall all be transferred to our canvas in their perfect measure. Aspasia, however, is only preserved to us in miniature: our proportions must be those of a colossus." | | style="text-align: left;" | "Next I have to depict Wisdom; and here I shall have occasion for many models, most of them ancient; one comes, like the lady herself, from Ionia. The artists shall be Aeschines and Socrates his master, most realistic of painters, for their heart was in their work. We could choose no better model of wisdom than Milesian Aspasia, the admired of the admirable 'Olympian'; her political knowledge and insight, her shrewdness and penetration, shall all be transferred to our canvas in their perfect measure. Aspasia, however, is only preserved to us in miniature: our proportions must be those of a colossus." | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: left;" | '''''Lucian''', ''A Portrait-Study'' | + | | style="text-align: left;" | '''''Lucian''', ''A Portrait-Study,'' XVII |

|} | |} | ||

| − | Although Athenian women were not accorded the same social and civic status as men, most Greek philosophers regarded women as being equally capable of developing the intellect and cultivating the soul. | + | Although Athenian women were not accorded the same social and civic status as men, most Greek philosophers regarded women as being equally capable of developing the intellect and cultivating the soul. An ideal society required the participation of both enlightened men and enlightened women. Women did not participate in the public schools, but if a woman was educated at home, as Aspasia was, she was respected for her accomplishments. Scholars have concluded that Aspasia was almost certainly a hetaera because of the freedom and authority with which she moved about in society. |

| − | Plutarch (46 – 127 | + | Plutarch (46 – 127 C.E.) accepts her as a significant figure both politically and intellectually and expresses his admiration for a woman who "managed as she pleased the foremost men of the state, and afforded the philosophers occasion to discuss her in exalted terms and at great length." [[Lucian]] calls Aspasia a "model of wisdom," "the admired of the admirable Olympian" and lauds "her political knowledge and insight, her shrewdness and penetration.” (Lucian, ''A Portrait Study,'' XVII.) A Syriac text, according to which Aspasia composed a speech and instructed a man to read it for her in the courts, confirms Aspasia's reputation as a rhetorician. Aspasia is said by [[Suda]], a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia, to have been "clever with regards to words," a sophist, and to have taught rhetoric. |

==References== | ==References== | ||

<div class="references-small"> | <div class="references-small"> | ||

| + | |||

===Primary sources (Greeks and Romans)=== | ===Primary sources (Greeks and Romans)=== | ||

| − | * Aristophanes, ''Acharnians'' | + | links Retrieved February 20, 2008. |

| − | * Athenaeus, ''Deipnosophistae'' | + | * Aristophanes, ''Acharnians.'' See original text in [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0240 Perseus program]. |

| − | * Cicero, ''De Inventione'' | + | * Athenaeus, ''Deipnosophistae.'' [http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/Literature.DeipnoSub University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center]. |

| − | * Diodorus Siculus, ''Library'' | + | * Cicero, ''De Inventione,'' I. See original text in the [http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/cicero/inventione1.shtml Latin Library]. |

| − | * Lucian, ''A Portrait Study'' | + | * Diodorus Siculus, ''Library,'' XII. See original text in [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0084:book=12:chapter=40:section=1/ Perseus program]. |

| − | * Plato, ''Menexenus'' | + | * Lucian, ''A Portrait Study.'' Translated in [http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/luc/wl3/wl303.htm sacred-texts] |

| − | * Plutarch, ''Pericles'' | + | * Plato, ''Menexenus.'' See original text in [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0180%3Atext%3DMenex. Perseus program]. |

| − | * Thucydides, ''The Peloponnesian War'' | + | * Plutarch, ''Pericles.'' See original text in [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0182%3Atext%3DPer/ Perseus program]. |

| − | * Xenophon, ''Memorabilia'' | + | * Thucydides, ''The Peloponnesian War,'' I and III. See original text in [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0200&query=book%3D%233 Perseus program]. |

| − | * Xenophon, ''Oeconomicus'' | + | * Xenophon, ''Memorabilia.'' See original text in [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0208 Perseus program]. |

| + | * Xenophon, ''Oeconomicus.'' Transated by [http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/1173 H.G. Dakyns]. | ||

| + | |||

===Secondary sources=== | ===Secondary sources=== | ||

| − | * | + | |

| − | * | + | *Adams, Henry Gardiner. ''A Cyclopaedia of Female Biography.'' 1857 Groombridge. |

| − | * | + | *Allen, Prudence. "The Pluralists: Aspasia," ''The Concept of Woman: The Aristotelian Revolution, 750 B.C.E..E. - A.D. 1250.'' Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0802842704, |

| − | * | + | *Arkins, Brian. "Sexuality in Fifth-Century Athens" ''Classics Ireland'' 1 (1994) |

| − | * | + | *Bicknell, Peter J. "Axiochus Alkibiadou, Aspasia and Aspasios." ''L'Antiquité Classique'' (1982) 51(3):240-250 |

| − | * | + | *Bolansée, Schepens, Theys, Engels. "Antisthenes of Athens." ''Die Fragmente Der Griechischen Historiker: A. Biography.'' Brill Academic Publishers, 1989. ISBN 9004110941 |

| − | * | + | *Brose, Margaret. "Ugo Foscolo and Giacomo Leopardi." ''A Companion to European Romanticism,'' edited by Michael Ferber. Blackwell Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1405110392 |

| − | * | + | *Duyckinck, G.L. and E.A. Duyckinc. ''Cyclopedia of American Literature.'' C. Scribner, 1856. |

| − | * | + | * Samons, Loren J., II and Charles W. Fornara. ''Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles.'' Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. |

| − | * | + | *Glenn, Cheryl. "Locating Aspasia on the Rhetorical Map." ''Listening to Their Voices.'' Univ of South Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN 157003272-X. |

| − | * | + | *Glenn, Cheryl. "Sex, Lies, and Manuscript: Refiguring Aspasia in the History of Rhetoric." ''Composition and Communication'' 45(4) (1994):180-199 |

| − | * | + | *Gomme, Arnold W. "The Position of Women in Athens in the Fifth and Fourth Centurie BC." ''Essays in Greek History & Literature.'' Ayer Publishing, 1977. ISBN 0836964818 |

| − | * | + | *Anderson, D.D. ''The Origins and Development of the Literature of the Midwest.'' |

| − | * | + | ''Dictionary of Midwestern Literature: Volume One: The Authors.'' by Philip A Greasley. Indiana University Press, 2001. ISBN 0253336090. |

| − | * | + | *Onq, Rory and Susan Jarratt, "Aspasia: Rhetoric, Gender, and Colonial Ideology," ''Reclaiming Rhetorica,'' edited by Andrea A. Lunsford. Berkeley: Pittsburgh: University of Pitsburgh Press, 1995. ISBN 0766194841 |

| − | * | + | * Alden, Raymond MacDonald. "Walter Savage Landor," ''Readings in English Prose of the Nineteenth Century.'' Kessinger Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0822955539 |

| − | * | + | *Henri, Madeleine M. ''Prisoner of History. Aspasia of Miletus and her Biographical Tradition.'' Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0195087127 |

| − | * | + | *Kagan, Donald. ''Pericles of Athens and the Birth of Democracy.'' The Free Press, 1991. ISBN 0684863952 |

| − | * | + | *Kagan, |first=Donald|title= "Athenian Politics on the Eve of the War," ''The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War.'' Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989. ISBN 0801495563 |

| − | * | + | *Kahn, Charles H. "Antisthenes," ''Plato and the Socratic Dialogue.'' Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521648300 |

| − | * | + | *__________. "Aeschines on Socratic Eros," ''The Socratic Movement,'' edited by Paul A. Vander Waerdt. Cornell University Press, 1994. ISBN 0801499038 |

| − | + | *Just, Roger. "Personal Relationships," ''Women in Athenian Law and Life.'' London: Routledge, 1991. ISBN 0415058414 | |

| − | * | + | *Loraux, Nicole. "Aspasie, l'étrangère, l'intellectuelle," ''La Grèce au Féminin.'' (in French) Belles Lettres, 2003. ISBN 2251380485 |

| − | * | + | *McClure, Laura. ''Spoken Like a Woman: Speech and Gender in Athenian Drama.'' Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 0691017301 "The City of Words: Speech in the Athenian Polis." |

| − | * | + | *McGlew, James F. ''Citizens on Stage: Comedy and Political Culture in the Athenian Democracy.'' University of Michigan Press, 2002. ISBN 0472112856 "Exposing Hypocrisie: Pericles and Cratinus' Dionysalexandros." |

| − | * | + | *Monoson, Sara. ''Plato's Democratic Entanglements.'' Hackett Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0691043663 "Plato's Opposition to the Veneration of Pericles." |

| + | *Nails, Debra. ''The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics.'' Princeton University Press, 2000. ISBN 0872205649 | ||

| + | *Ostwald, M. ''The Cambridge Ancient History,'' edited by David M. Lewis, John Boardman, J. K. Davies, M. Ostwald (Volume V) Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 052123347X "Athens as a Cultural Center." | ||

* Paparrigopoulos, Konstantinos (-Karolidis, Pavlos)(1925), ''History of the Hellenic Nation (Volume Ab)''. Eleftheroudakis (in Greek). | * Paparrigopoulos, Konstantinos (-Karolidis, Pavlos)(1925), ''History of the Hellenic Nation (Volume Ab)''. Eleftheroudakis (in Greek). | ||

| − | * | + | *Podlecki, A.J. ''Perikles and His Circle.'' Routledge (UK), 1997. ISBN 0415067944 |

| − | * | + | *Powell, Anton. ''The Greek World.'' Routledge (UK), 1995. ISBN 0415060311 "Athens' Pretty Face: Anti-feminine Rhetoric and Fifth-century Controversy over the Parthenon." |

| − | * | + | *Rose, Martha L. ''The Staff of Oedipus.'' University of Michigan Press, 2003. ISBN 0472113399 "Demosthenes' Stutter: Overcoming Impairment." |

| − | * | + | *Rothwell, Kenneth Sprague. ''Politics and Persuasion in Aristophanes' Ecclesiazusae.'' Brill Academic Publishers, 1990. ISBN 9004091858 "Critical Problems in the Ecclesiazusae" |

| − | * | + | *Smith, William. ''A History of Greece.'' R. B. Collins, 1855. "Death and Character of Pericles." |

| − | * | + | *Southall, Aidan. ''The City in Time and Space.'' Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0521784328 "Greece and Rome." |

| − | * | + | *Stadter, Philip A. ''A Commentary on Plutarch's Pericles.'' University of North Carolina Press, 1989. ISBN 0807818615 |

| − | * | + | *Sykoutris, Ioannis. ''Symposium (Introduction and Comments)'' -in Greek Estia, 1934. |

| − | * | + | *Taylor, A. E. ''Plato: The Man and His Work.'' Courier Dover Publications, 2001. ISBN 0486416054 "Minor Socratic Dialogues: Hippias Major, Hippias Minor, Ion, Menexenus." |

| − | * | + | *Taylor, Joan E. ''Jewish Women Philosophers of First-Century Alexandria.'' Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 0199259615 "Greece and Rome." |

| − | * | + | *Wider, Kathleen, "Women philosophers in the Ancient Greek World: Donning the Mantle." ''Hypatia'' 1 (1)(1986):21-62 |

</div> | </div> | ||

==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

<div class="references-small"> | <div class="references-small"> | ||

| − | * | + | *Atherton, Gertrude. ''The Immortal Marriage.'' Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1417915595 |

| − | * | + | * Becq de Fouquières, Louis. ''Aspasie de Milet.'' (in French) Didier, 1872. |

| − | * | + | * Hamerling, Louis. ''Aspasia: a Romance of Art and Love in Ancient Hellas.'' Geo. Gottsberger Peck, 1893 |

| − | * | + | *Savage Landor, Walter. ''Pericles And Aspasia.'' Kessinger Publishing, 2004 ISBN 0766189589 |

</div> | </div> | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved August 18, 2023. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | * ''Encyclopaedia Romana'' [http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/greece/hetairai/aspasia.html Aspasia of Miletus]. | |

| − | + | * Henry, Madeleine and N.S. Gill. [http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/philosophers/a/Aspasia.htm "Aspasia of Miletus - Prisoner of History"]. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===General Philosophy Sources=== | ===General Philosophy Sources=== | ||

*[http://plato.stanford.edu/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | ||

*[http://www.iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[http://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online] | *[http://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online] | ||

*[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg] | *[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg] | ||

| Line 224: | Line 162: | ||

[[Category:philosophers]] | [[Category:philosophers]] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Philosophy]] |

| − | |||

{{Credit|77851853}} | {{Credit|77851853}} | ||

Latest revision as of 04:50, 18 August 2023

Aspasia (c. 470 B.C.E. - 400 B.C.E.) Greek: Ἀσπασία) was a woman rhetorician and philosopher in ancient Greece, famous for her romantic involvement with the Athenian statesman Pericles. She was born in the city of Miletus in Asia Minor, and around 450 B.C.E. traveled to Athens, where she spent the rest of her life. She is thought to have exercised considerable influence on Pericles, both politically and philosophically. Plato suggested that she helped compose Pericles' famous Funeral Oratory, and that she trained Pericles and Socrates in oratory. After the death of Pericles she was allegedly involved with Lysicles, another Athenian statesman and general. She had a son with Pericles, Pericles the Younger, who was elected general and was executed after a naval disaster at the Battle of Arginusae.

Aspasia appears in the philosophical writings of Xenophon, Aeschines Socraticus, Plato and Antisthenes and is regarded by modern scholars as an exceptional person who distinguished herself due to her political influence and intellectual charisma. Most of what is known about her comes from the comments of ancient philosophers and writers, some of whom were comic poets who wished to disparage Pericles, rather than from factual accounts. Scholars believe that most of the stories told about her are myths reflecting her status and influence.

Origin

Aspasia was born around 470 B.C.E. in the Ionian Greek colony of Miletus (in the modern Aydin Province, Turkey). Her father's name was Axiochus. She was a free woman, not a Carian prisoner-of-war turned slave as some ancient sources claim. She probably belonged to a wealthy and cultured family, because her parents provided her with an extensive education.

The circumstances that took her to Athens are not known. The discovery of a fourth-century grave inscription that mentions the names of Axiochus and Aspasius has led historian Peter J. Bicknell to attempt a reconstruction of Aspasia's family background and Athenian connections. His theory connects her to Alcibiades II of Scambonidae, who was ostracized from Athens in 460 B.C.E. and may have spent his exile in Miletus. Bicknell conjectures that, following his exile, the elder Alcibiades went to Miletus, where he married the daughter of a certain Axiochus. Alcibiades apparently returned to Athens with his new wife and her younger sister, Aspasia. Bicknell argues that the first child of this marriage was named Axiochus (uncle of the famous Alcibiades) and the second Aspasios. He also maintains that Pericles met Aspasia through his close connections with Alcibiades's household.

Life in Athens

| ”And so Aspasia, as some say, was held in high favor by Pericles because of her rare political wisdom. Socrates sometimes came to see her with his disciples, and his intimate friends brought their wives to her to hear her discourse, although she presided over a business that was any- thing but honest or even reputable, since she kept a house of young courtesans. And Aeschines says that Lysicles the sheep-dealer, a man of low birth and nature, came to be the first man at Athens by living with Aspasia after the death of Pericles. And in the “Menexenus” of Plato, even though the first part of it be written in a sportive vein, there is, at any rate, thus much of fact, that the woman had the reputation of associating with many Athenians as a teacher of rhetoric. However, the affection which Pericles had for Aspasia seems to have been rather of an amatory sort. For his own wife was near of kin to him, and had been wedded first to Hipponicus, to whom she bore Callias, surnamed the Rich; she bore also, as the wife of Pericles, Xanthippus and Paralus. Afterwards, since their married life was not agreeable, he legally bestowed her upon another man, with her own consent, and himself took Aspasia, and loved her exceedingly. Twice a day, as they say, on going out and on coming in from the market-place, he would salute her with a loving kiss. But in the comedies she is styled now the New Omphale, now Deianeira, and now Hera. Cratinus flatly called her a prostitute … So renowned and celebrated did Aspasia become, they say, that even Cyrus, the one who went to war with the Great King for the sovereignty of the Persians, gave the name of Aspasia to that one of his concubines whom he loved best, who before was called Milto. She was a Phocaean by birth, daughter of one Hermotimus, and, after Cyrus had fallen in battle, was carried captive to the King, and acquired the greatest influence with him. These things coming to my recollection as I write, it were perhaps unnatural to reject and pass them by." (Plutarch, Pericles, XXIV) |

| From Aristophanes' comedic play, The Acharnians (523-533) |

According to the disputed statements of the ancient writers and some modern scholars, in Athens Aspasia became a hetaera. Hetaerae were professional entertainers of upper class men, as well as courtesans. They differed from most Athenian women in being well educated, having independence, and paying taxes. According to Plutarch, Aspasia was compared to the famous Thargelia, another renowned Ionian hetaera of ancient times.

Being a foreigner and possibly a hetaera, Aspasia was freed from the legal restraints that traditionally confined married women to their homes and could therefore participate in the public life of the city. After the statesman Pericles divorced his first wife (c. 445 B.C.E.), Aspasia began to live with him, although her marital status remains disputed as she was not a citizen of Athens. Their son, Pericles the Younger, was probably born before 440 B.C.E. because it is reported that she later bore another child to Lysicles, around 428 B.C.E..

Aspasia was noted for her ability as a conversationalist and adviser rather than merely an object of physical beauty. According to Plutarch, their house became an intellectual centre in Athens, attracting the most prominent writers and thinkers, including the philosopher Socrates. The biographer writes that Athenians used to bring their wives to hear her discourses.

Personal and Judicial Attacks

Aspasia’s relationship with Pericles and her consequent political influence aroused public sentiment against her. In 440 B.C.E., Samos was at war with Miletus over Priene, an ancient city of Ionia in the foot-hills of Mycale. The Milesians came to Athens to plead their case against the Samians, but when the Athenians ordered the two sides to stop fighting and submit the case to arbitration at Athens, the Samians refused. In response, Pericles passed a decree dispatching an expedition to Samos. The campaign proved to be difficult and the Athenians endured heavy casualties before Samos was defeated. According to Plutarch, it was thought that Aspasia, who came from Miletus, was responsible for the Samian War, and that Pericles had decided against and attacked Samos to gratify her.

Plutarch reports that before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (431 B.C.E. - 404 B.C.E.), Pericles, some of his closest associates and Aspasia faced a series of personal and legal attacks. Aspasia, in particular, was accused of corrupting the women of Athens in order to satisfy Pericles' desires. According to Plutarch, she was put on trial for impiety, with the comic poet Hermippus as prosecutor. All these accusations were probably unproven slanders, but the experience was bitter for the Athenian leader. Although Aspasia was acquitted thanks to a rare emotional outburst of Pericles, his friend, Phidias, died in prison. Another friend of his, Anaxagoras, was attacked by the Ecclesia (the Athenian Assembly) for his religious beliefs. It is possible that Plutarch’s account of Aspasia's trial and acqittal was a historical invention based on earlier slanders and ribald comedies.

In his play, The Acharnians, Aristophanes blames Aspasia for the Peloponnesian War, claiming that the Megarian decree of Pericles, which excluded Megara from trade with Athens or its allies, was retaliation for prostitutes being kidnapped from the house of Aspasia by Megarians. Plutarch also reports the slurs of other comic poets, such as Eupolis and Cratinus. Douris appears to have promoted the view that Aspasia instigated both the Samian and Peloponnesian Wars. Aspasia was labeled the "New Omphale," "Deianira," "Hera" and "Helen." (Omphale and Deianira were respectively the Lydian queen who owned Heracles as a slave for a year and his long-suffering wife. The comedians parodied Pericles for resembling a Heracles under the control of an Omphale-like Aspasia.) Further attacks on Pericles' relationship with Aspasia are reported by Athenaeus. Pericles's own son, Xanthippus, who had political ambitions, did not hesitate to slander his father over his domestic affairs.

Later Years and Death

| "Thus far the evil was not serious and we were the only sufferers. But now some young drunkards go to Megara and carry off the courtesan Simaetha; the Megarians, hurt to the quick, run off in turn with two harlots of the house of Aspasia; and so for three whores Greece is set ablaze. Then Pericles, aflame with ire on his Olympian height, let loose the lightning, caused the thunder to roll, upset Greece and passed an edict, which ran like the song, That the Megarians be banished both from our land and from our markets and from the sea and from the continent." |

| From Aristophanes' comedic play, The Acharnians (523-533) |

The return of soldiers from the battle front brought the plague to Athens. In 429 B.C.E., Pericles witnessed the death of his sister and of both his legitimate sons from his first wife, Xanthippus and his beloved Paralus, from the disease. With his morale undermined, he burst into tears, and not even Aspasia could console him. Just before his death, the Athenians allowed a change in the citizenship law that made his half-Athenian son with Aspasia, Pericles the Younger, a citizen and legitimate heir. Pericles himself had proposed the law in 451 B.C.E. confining Athenian citizenship to those of Athenian parentage on both sides, to prevent aristocratic families from forming alliances with other cities. Pericles died in the autumn of 429 B.C.E..

Plutarch cites a dialogue by Aeschines Socraticus (now lost), to the effect that after Pericles's death Aspasia lived with Lysicles, an Athenian general and democratic leader, with whom she had another son; and that she helped him rise to a high position in Athens. Lysicles was killed in action in 428 B.C.E., and after his death there is no further record of Aspasia. The date given by most historians for her death (c. 401 B.C.E. - 400 B.C.E.) is based on the assessment that Aspasia died before the execution of Socrates in 399 B.C.E., a chronology which is implied in the structure of Aeschines' Aspasia.

References in Philosophical Works

Ancient philosophical works

| "Now, since it is thought that he proceeded thus against the Samians to gratify Aspasia, this may be a fitting place to raise the query what great art or power this woman had, that she managed as she pleased the foremost men of the state, and afforded the philosophers occasion to discuss her in exalted terms and at great length." |

| Plutarch, Pericles, XXIV |

Aspasia appears in the philosophical writings of Plato, Xenophon, Aeschines Socraticus and Antisthenes. Some scholars suggest that Plato was impressed by her intelligence and wit and based his character Diotima in Symposium on her, while others believe that Diotima was in fact a historical figure. According to Charles Kahn, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, Diotima is in many respects Plato's response to Aeschines' Aspasia.

In Menexenus, Plato satirizes Aspasia's relationship with Pericles, and quotes Socrates as claiming that she trained many orators. Socrates' intention is to cast aspersions on Pericles' rhetorical abilities, claiming that, since the Athenian statesman was educated by Aspasia, he would be superior in rhetoric to someone educated by Antiphon. He also attributes authorship of Pericles’ Funeral Oration to Aspasia and attacks his contemporaries' veneration of Pericles. Kahn maintains that Plato has taken the idea of Aspasia as teacher of rhetoric for Pericles and Socrates from Aeschines.

Xenophon mentions Aspasia twice in his Socratic writings: in Memorabilia and in Oeconomicus. In both cases her advice is recommended to Critobulus by Socrates. In Memorabilia Socrates quotes Aspasia as saying that the matchmaker should report truthfully on the good characteristics of the man. In Oeconomicus Socrates defers to Aspasia as being the one more knowledgeable about household management and the economic partnership between husband and wife.

Aeschines Socraticus and Antisthenes each named a Socratic dialogue after Aspasia (though neither survives except in fragments). Our major sources for Aeschines Socraticus' Aspasia are Athenaeus, Plutarch, and Cicero. In the dialogue, Socrates recommends that Callias send his son Hipponicus to Aspasia for instructions. When Callias recoils at the notion of a female teacher, Socrates notes that Aspasia had favorably influenced Pericles and, after his death, Lysicles. In a section of the dialogue, preserved in Latin by Cicero, Aspasia figures as a "female Socrates," counseling first Xenophon's wife and then Xenophon (not the famous historian Xenophon) himself about acquiring virtue through self-knowledge. Aeschines presents Aspasia as a teacher and inspirer of excellence, connecting these virtues with her status as hetaira.

Of Antisthenes' Aspasia only two or three quotations are extant. This dialogue contains both aspersions and anecdotes about Pericles. Antisthenes appears to have attacked not only Aspasia, but the entire family of Pericles, including his sons. The philosopher believes that the great statesman chose the life of pleasure over virtue, presenting Aspasia as the personification of a life of self-indulgence.

| "All argumentation, then, is to be carried on either by induction or by deduction. Induction is a form of argument which leads the person with whom one is arguing to give assent to certain undisputed facts; through this assent it wins his approval of a doubtful proposition because this resembles the facts to which he has assented. For instance, in a dialogue by Aeschines Socraticus Socrates reveals that Aspasia reasoned thus with Xenophon's wife and with Xenophon himself: "Please tell me, madam, if your neighbour had a better gold ornament than you have, would you prefer that one or your own?" "That one," she replied. "Now, if she had dresses and other feminine finery more expensive than you have, would you prefer yours or hers?" "Hers, of course," she replied. "Well now, if she had a better husband than you have, would you prefer your husband or hers?" At this the woman blushed. But Aspasia then began to speak to Xenophon. "I wish you would tell me, Xenophon," she said, "if your neighbour had a better horse than yours, would you prefer your horse or his?" "His" was his answer. "And if he had a better farm than you have, which farm would your prefer to have?" The better farm, naturally," he said. "Now if he had a better wife than you have, would you prefer yours or his?" And at this Xenophon, too, himself was silent. Then Aspasia: "Since both of you have failed to tell me the only thing I wished to hear, I myself will tell you what you both are thinking. That is, you, madam, wish to have the best husband, and you, Xenophon, desire above all things to have the finest wife. Therefore, unless you can contrive that there be no better man or finer woman on earth you will certainly always be in dire want of what you consider best, namely, that you be the husband of the very best of wives, and that she be wedded to the very best of men." (Cicero, Institutio Oratoria, V.11. 27-29) |

| From Aristophanes' comedic play, The Acharnians (523-533) |

Modern literature

Aspasia appears in several significant works of modern literature. Her romantic attachment with Pericles particularly inspired the romanticists of the nineteenth century and the historical novelists of the twentieth century. In 1835 Lydia Child, an American abolitionist, novelist, and journalist published Philothea, a classical romance set in the days of Pericles and Aspasia. This book is regarded as her most successful and elaborate because the female characters, and especially Aspasia, are portrayed with beauty and delicacy. In 1836 Walter Savage Landor, an English writer and poet, published Pericles and Aspasia, a rendering of classical Athens through a series of imaginary letters, which contain numerous poems. The letters are frequently unfaithful to actual history but attempt to capture the spirit of the Age of Pericles. In 1876 Robert Hamerling published his novel Aspasia, a book about the manners and morals of the Age of Pericles and a work of cultural and historical interest. Giacomo Leopardi, an Italian poet influenced by the movement of romanticism, published a group of five poems known as the circle of Aspasia. The poems were inspired by his painful experience of desperate and unrequited love for a woman named Fanny Targioni Tozzetti, whom he called “Aspasia” after the companion of Pericles.

In 1918 novelist and playwright George Cram Cook produced his first full-length play, The Athenian Women, portraying Aspasia leading a strike for peace. American writer Gertrude Atherton in The Immortal Marriage (1927) recreates the story of Pericles and Aspasia, and illustrates the period of the Samian War, the Peloponnesian War and the plague.

Significance

Historically, Aspasia's name is closely associated with Pericles's glory and fame. Her reputation as a philosopher and rhetorician is mostly anecdotal, as are the details about her personal life. Some scholars suggest that Plato derived his portrayal of Aspasia as an intellectual from earlier Greek comedies, and that his remarks that she trained Pericles and Socrates in oratory should not be construed as historical fact. Whether the stories about Aspasia are fact or legend, no other woman achieved the same stature in ancient Greek history or literature. She is regarded by modern scholars as an exceptional person who distinguished herself due to her political influence and intellectual charisma.

| "Next I have to depict Wisdom; and here I shall have occasion for many models, most of them ancient; one comes, like the lady herself, from Ionia. The artists shall be Aeschines and Socrates his master, most realistic of painters, for their heart was in their work. We could choose no better model of wisdom than Milesian Aspasia, the admired of the admirable 'Olympian'; her political knowledge and insight, her shrewdness and penetration, shall all be transferred to our canvas in their perfect measure. Aspasia, however, is only preserved to us in miniature: our proportions must be those of a colossus." |

| Lucian, A Portrait-Study, XVII |

Although Athenian women were not accorded the same social and civic status as men, most Greek philosophers regarded women as being equally capable of developing the intellect and cultivating the soul. An ideal society required the participation of both enlightened men and enlightened women. Women did not participate in the public schools, but if a woman was educated at home, as Aspasia was, she was respected for her accomplishments. Scholars have concluded that Aspasia was almost certainly a hetaera because of the freedom and authority with which she moved about in society.

Plutarch (46 – 127 C.E.) accepts her as a significant figure both politically and intellectually and expresses his admiration for a woman who "managed as she pleased the foremost men of the state, and afforded the philosophers occasion to discuss her in exalted terms and at great length." Lucian calls Aspasia a "model of wisdom," "the admired of the admirable Olympian" and lauds "her political knowledge and insight, her shrewdness and penetration.” (Lucian, A Portrait Study, XVII.) A Syriac text, according to which Aspasia composed a speech and instructed a man to read it for her in the courts, confirms Aspasia's reputation as a rhetorician. Aspasia is said by Suda, a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia, to have been "clever with regards to words," a sophist, and to have taught rhetoric.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary sources (Greeks and Romans)

links Retrieved February 20, 2008.

- Aristophanes, Acharnians. See original text in Perseus program.

- Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae. University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center.

- Cicero, De Inventione, I. See original text in the Latin Library.

- Diodorus Siculus, Library, XII. See original text in Perseus program.

- Lucian, A Portrait Study. Translated in sacred-texts

- Plato, Menexenus. See original text in Perseus program.

- Plutarch, Pericles. See original text in Perseus program.

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, I and III. See original text in Perseus program.

- Xenophon, Memorabilia. See original text in Perseus program.

- Xenophon, Oeconomicus. Transated by H.G. Dakyns.

Secondary sources

- Adams, Henry Gardiner. A Cyclopaedia of Female Biography. 1857 Groombridge.

- Allen, Prudence. "The Pluralists: Aspasia," The Concept of Woman: The Aristotelian Revolution, 750 B.C.E. - A.D. 1250. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0802842704,

- Arkins, Brian. "Sexuality in Fifth-Century Athens" Classics Ireland 1 (1994)

- Bicknell, Peter J. "Axiochus Alkibiadou, Aspasia and Aspasios." L'Antiquité Classique (1982) 51(3):240-250

- Bolansée, Schepens, Theys, Engels. "Antisthenes of Athens." Die Fragmente Der Griechischen Historiker: A. Biography. Brill Academic Publishers, 1989. ISBN 9004110941

- Brose, Margaret. "Ugo Foscolo and Giacomo Leopardi." A Companion to European Romanticism, edited by Michael Ferber. Blackwell Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1405110392

- Duyckinck, G.L. and E.A. Duyckinc. Cyclopedia of American Literature. C. Scribner, 1856.

- Samons, Loren J., II and Charles W. Fornara. Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

- Glenn, Cheryl. "Locating Aspasia on the Rhetorical Map." Listening to Their Voices. Univ of South Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN 157003272-X.

- Glenn, Cheryl. "Sex, Lies, and Manuscript: Refiguring Aspasia in the History of Rhetoric." Composition and Communication 45(4) (1994):180-199

- Gomme, Arnold W. "The Position of Women in Athens in the Fifth and Fourth Centurie BC." Essays in Greek History & Literature. Ayer Publishing, 1977. ISBN 0836964818

- Anderson, D.D. The Origins and Development of the Literature of the Midwest.

Dictionary of Midwestern Literature: Volume One: The Authors. by Philip A Greasley. Indiana University Press, 2001. ISBN 0253336090.

- Onq, Rory and Susan Jarratt, "Aspasia: Rhetoric, Gender, and Colonial Ideology," Reclaiming Rhetorica, edited by Andrea A. Lunsford. Berkeley: Pittsburgh: University of Pitsburgh Press, 1995. ISBN 0766194841

- Alden, Raymond MacDonald. "Walter Savage Landor," Readings in English Prose of the Nineteenth Century. Kessinger Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0822955539

- Henri, Madeleine M. Prisoner of History. Aspasia of Miletus and her Biographical Tradition. Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0195087127

- Kagan, Donald. Pericles of Athens and the Birth of Democracy. The Free Press, 1991. ISBN 0684863952

- Kagan, |first=Donald|title= "Athenian Politics on the Eve of the War," The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989. ISBN 0801495563

- Kahn, Charles H. "Antisthenes," Plato and the Socratic Dialogue. Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521648300

- __________. "Aeschines on Socratic Eros," The Socratic Movement, edited by Paul A. Vander Waerdt. Cornell University Press, 1994. ISBN 0801499038

- Just, Roger. "Personal Relationships," Women in Athenian Law and Life. London: Routledge, 1991. ISBN 0415058414

- Loraux, Nicole. "Aspasie, l'étrangère, l'intellectuelle," La Grèce au Féminin. (in French) Belles Lettres, 2003. ISBN 2251380485

- McClure, Laura. Spoken Like a Woman: Speech and Gender in Athenian Drama. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 0691017301 "The City of Words: Speech in the Athenian Polis."

- McGlew, James F. Citizens on Stage: Comedy and Political Culture in the Athenian Democracy. University of Michigan Press, 2002. ISBN 0472112856 "Exposing Hypocrisie: Pericles and Cratinus' Dionysalexandros."

- Monoson, Sara. Plato's Democratic Entanglements. Hackett Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0691043663 "Plato's Opposition to the Veneration of Pericles."

- Nails, Debra. The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics. Princeton University Press, 2000. ISBN 0872205649

- Ostwald, M. The Cambridge Ancient History, edited by David M. Lewis, John Boardman, J. K. Davies, M. Ostwald (Volume V) Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 052123347X "Athens as a Cultural Center."

- Paparrigopoulos, Konstantinos (-Karolidis, Pavlos)(1925), History of the Hellenic Nation (Volume Ab). Eleftheroudakis (in Greek).

- Podlecki, A.J. Perikles and His Circle. Routledge (UK), 1997. ISBN 0415067944

- Powell, Anton. The Greek World. Routledge (UK), 1995. ISBN 0415060311 "Athens' Pretty Face: Anti-feminine Rhetoric and Fifth-century Controversy over the Parthenon."

- Rose, Martha L. The Staff of Oedipus. University of Michigan Press, 2003. ISBN 0472113399 "Demosthenes' Stutter: Overcoming Impairment."

- Rothwell, Kenneth Sprague. Politics and Persuasion in Aristophanes' Ecclesiazusae. Brill Academic Publishers, 1990. ISBN 9004091858 "Critical Problems in the Ecclesiazusae"

- Smith, William. A History of Greece. R. B. Collins, 1855. "Death and Character of Pericles."

- Southall, Aidan. The City in Time and Space. Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0521784328 "Greece and Rome."

- Stadter, Philip A. A Commentary on Plutarch's Pericles. University of North Carolina Press, 1989. ISBN 0807818615

- Sykoutris, Ioannis. Symposium (Introduction and Comments) -in Greek Estia, 1934.

- Taylor, A. E. Plato: The Man and His Work. Courier Dover Publications, 2001. ISBN 0486416054 "Minor Socratic Dialogues: Hippias Major, Hippias Minor, Ion, Menexenus."

- Taylor, Joan E. Jewish Women Philosophers of First-Century Alexandria. Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 0199259615 "Greece and Rome."

- Wider, Kathleen, "Women philosophers in the Ancient Greek World: Donning the Mantle." Hypatia 1 (1)(1986):21-62

Further reading

- Atherton, Gertrude. The Immortal Marriage. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1417915595

- Becq de Fouquières, Louis. Aspasie de Milet. (in French) Didier, 1872.

- Hamerling, Louis. Aspasia: a Romance of Art and Love in Ancient Hellas. Geo. Gottsberger Peck, 1893

- Savage Landor, Walter. Pericles And Aspasia. Kessinger Publishing, 2004 ISBN 0766189589

External links

All links retrieved August 18, 2023.

- Encyclopaedia Romana Aspasia of Miletus.

- Henry, Madeleine and N.S. Gill. "Aspasia of Miletus - Prisoner of History".

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.