Difference between revisions of "Apis" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) (New page: {{started}} thumb|230px|right|Statue of Apis, [[Thirtieth dynasty of Egypt|30th Dynasty, Louvre]] In Egyptian mythology, '''A...) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (21 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | [[Image:Louvres-antiquites-egyptiennes-p1020068.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Louvres-antiquites-egyptiennes-p1020068.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Statue of Apis, 30th Dynasty, [[Louvre]]. Note the fractured remains of the sun-disk and uraeus (serpent crown) between his horns.]] |

| − | In [[ | + | In [[Ancient Egypt]], '''Apis''' or ''Hapis'' (alternatively spelt ''Hapi-ankh'') was a bull-deity worshiped in the Memphis region and thought to represent rulership and masculine vigor. Though originally a local deity, his popularity grew throughout the dynastic history, such that, by the Ptolemaic period, he was "a kind of national mascot."<ref>Geraldine Pinch, ''Handbook of Egyptian mythology.'' (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002), 105.</ref> The worship of Apis was certainly the most popular of the three great bull cults of ancient Egypt (the others being the bulls [[Mnevis]] and [[Buchis]].) |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Though Hape (Apis) is named on some of the earliest monuments in ancient Egypt, the most detailed accounts of his cult can be traced back to the New Kingdom period (1570–1070 B.C.E.). He was originally seen as "the renewal of the life" of the Memphite god [[Ptah]], but after death he became Osorapis, (the [[Osiris]] Apis).<ref>In this form, he was assimilated into Osiris, a process that was also understood to occur with the spirits of dead humans.</ref>. Under the Ptolemaic dynasty, this deity became [[Serapis]], a Hellenistic syncretism between the popular Egyptian cult and the iconography (and characterization) of the Greek god, [[Hades]]. | ||

| − | + | ==Apis in an Egyptian Context== | |

| + | {{Hiero|Apis|<hiero>V28-Aa5:Q3-E1</hiero> | ||

| + | <br/>or<br/><hiero>G39</hiero> | ||

| + | <br/>or<br/><hiero>Aa5:Q3-G43</hiero> | ||

| + | <br/>or<br/><hiero>Aa5:Q3</hiero>|align=right|era=egypt}} | ||

| + | As an Egyptian deity, Apis belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system developed in the [[Nile]] river basin from earliest prehistory to 525 B.C.E.<ref>This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Adolf Erman. ''A handbook of Egyptian religion,'' Translated by A. S. Griffith. (London: Archibald Constable, 1907), 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.</ref> Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.<ref>The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).</ref> The cults within this framework, whose beliefs comprise the myths we have before us, were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.<ref>These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Dimitri Meeks and Christine Meeks-Favard. ''Daily life of the Egyptian gods,'' Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996), 34-37).</ref> Despite this apparently unlimited diversity, however, the gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “the Egyptian gods are imperfect as individuals. If we compare two of them … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”<ref>Henri Frankfort. ''Ancient Egyptian Religion.'' (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961), 25-26.</ref> One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanental—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.<ref>Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.</ref> Thus, those who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Also, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e., the cult of [[Amun-Re]], which unified the domains of [[Amun]] and [[Re]]), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.<ref>Frankfort, 20-21.</ref> | ||

| − | + | The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely appropriate to (and defined by) the geographical and calendrical realities of its believer’s lives. Unlike the beliefs of the [[Hebrews]], [[Mesopotamia|Mesopotamians]] and others within their cultural sphere, the Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.<ref>Jan Assmann. ''In search for God in ancient Egypt,'' Translated by David Lorton. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (James Henry Breasted. ''Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt.'' (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986), 8, 22-24).</ref> The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was ultimately defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.<ref>Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.</ref> Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tended to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead, with a particular focus on the relationship between the gods and their human constituents. | |

| − | + | Given that Apis (as deity) was actually understood to be the sacred bull, his cult presents another permutation of the highly concrete and immanental understanding of theology common in Ancient Egypt. | |

| − | The cult of the Apis bull | + | ==Mythological Accounts and Religious Manifestations== |

| + | The cult of the Apis bull is one of the most archaic in the Egyptian religious system, hearkening back to the earliest epoch of their dynastic history. From the outset, it appears that he was a fertility god connected to grain and the herds. However, his most important affiliation was with the pharaoh, as he was seen to symbolize the king’s courageous heart, great strength, virility, and fighting spirit. This association is borne out in religious iconography, as the bull god was occasionally depicted with the sun-disk between his horns—a clear reference to [[Ra]], the divine ruler ''par excellence.''<ref> However, this iconographic flourish is of a comparatively later date, as [[Ra]] had initially been associated with the Mnevis bull. Frankfort, 10; Wilkinson, 171.</ref> Further, the Apis bull is unique in their iconographic system in that he is the only Egyptian god represented solely as an animal, and never as a human with an animal's head. This is likely because the physical bull, that dwelt in an enclosure at the temple in Memphis, was literally seen to be the god.<ref> However, this identity only applied to the specific animal, which was recognized by various physiognomic features, not to the species as a whole. Budge (1969), Vol. I, 27; Frankfort, 10.</ref> In this way, Apis is more strongly affiliated with the particulars of his animal existence than are the other deities in pantheon, who are merely ''represented'' by their animal forms (i.e., [[Horus]] and the falcon, [[Bast]] and the cat, [[Sebek]] and the crocodile, [[Thoth]] and the ibis).<ref>Budge (1969), Vol. II, 195-197; Meeks and Favard-Meeks, 136-138; Frankfort, 10.</ref> | ||

| − | Apis was | + | === The Herald of Ptah === |

| + | In the original Memphite cult, Apis was conceived as Herald of [[Ptah]], the chief god of the area. However, the specifics of the relationship between the two deities was complex: "Ptah was never depicted as a bull or believed to be incarnate in a bull; but the Apis bull was called 'the living Apis, the herald of Ptah, who carries the truth upwards to him of the lovely face (Ptah).'" <ref>Frankfort, 10.</ref> This divine bovine, as a herald/manifestation of the god, was understood to be unique, in that there was only ever one Apis bull at a given time. | ||

| − | + | These beliefs were complemented by a complex system of practices depicting the proper selection and veneration of the ''Bull of Ptah.'' Since the bovines in the region where Ptah was worshiped exhibited white patterning on their mainly black bodies, a system of beliefs developed concerning which types of markings a potential Apis bull required in order to be suitable to its role. Specifically, it was required to have a white triangle on its forehead, a white vulture wing outline on its back, a scarab-shaped lump under its tongue, a white crescent moon shape on its right flank, and double hairs on its tail.<ref>Richard H. Wilkinson. ''The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt.'' (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 171.</ref> A bull that matched these markings was selected from the herd, brought to a temple, given a harem of cows, and worshiped as a manifestation of the [[Ptah|craftsman god]]. His mother, who was believed to have conceived her divine offspring after being impregnated by a beam of light from the heavens, was also revered. At the temple, Apis was used as an [[oracle]], his movements being interpreted as prophecies. His breath was also believed to cure disease, and his presence was thought to bless those around with virility. As a result, the temples were constructed with a window that would allow the public to bask in his holy proximity. Further, this spiritual good was made available to the populace as a whole on certain festival days, when the god would be led through the streets of the city, bedecked with jewelry and flowers. Upon the animal's death, it would be mourned, mummified, and celebrated, after which point the new Apis would be found. These funerary elements came to be important components of the god's cult around the time of the conflation of [[Osiris]] with Ptah, a development that also led to a redefinition of the bovine god (as [[#Ka of Osiris|described below]]).<ref>When excavating the Serapeum (Temple of Apis) at Memphis, Mariette revealed the tombs of over sixty animals, ranging from the time of Amenophis III (1391–1353 B.C.E.) to the Ptolemaic dynasty (305-330 B.C.E.). Steles describing the regnal dates of the animals, often including the names of their mother cows and their places of birth, were also found at many of these sites. Meeks and Favard-Meeks, 136-140; Françoise Dunand and Christiane Zivie-Coche. ''Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.,'' Translated from the French by David Lorton. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004), 306; Jones, ''passim''. See also: ''Serapeum'' at [http://www.aldokkan.com/geography/serapeum.htm aldokkan.com], retrieved July 22, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | ===Ka of Osiris=== | |

| + | When Osiris absorbed the identity of Ptah, becoming ''Ptah-Seker-Osiris,'' the Apis bull became seen as an aspect of Osiris rather than Ptah. Since Osiris was lord of the dead, Apis then became known as the ''living deceased one,'' whose cultic significance only increased with the death of his current incarnation. As he now represented Osiris, when the Apis bull reached the age of twenty-eight, the age when Osiris was said to have been killed by [[Set]], symbolic of the lunar month, and the new moon, the bull was put to death with great ceremony.<ref>Wilkinson, 172.</ref> There is evidence that parts of the body of the Apis bull were eaten by the pharaoh and his priests to absorb the bull god's great strength. As a form of Osiris, lord of the dead, it was believed that to be under the protection of the Apis bull would give the person control over the four winds in the afterlife.<ref>Wilkinson, 170-172; Meeks and Favard-Meeks, 138-139.</ref> | ||

| − | + | By the New Kingdom, the remains of the Apis bulls were interred at the cemetery of Saqqara. The earliest known burial in Saqqara was performed in the reign of Amenhotep III (1391–1353 B.C.E.) by his son Thutmosis; afterwards, seven more bulls were buried nearby. Ramesses II initiated Apis burials in what is now known as ''the Serapeum,'' an underground complex of burial chambers at Saqqara for the sacred bulls, a site used through the rest of Egyptian history into the reign of Cleopatra VII.<ref>Meeks and Favard-Meeks, 136-140; Dunand, 306; Michael Jones, "The Temple of Apis in Memphis," ''The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology'' 76 (1990): 141-147, ''passim''; Dunand, 331, 333. See also: ''Serapeum'' at [http://www.aldokkan.com/geography/serapeum.htm aldokkan.com], retrieved July 22, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Unlike the cults of most of the other Egyptian deities, the worship of the Apis bull was continued by the Greeks and after them by the Romans, and lasted until almost 400 C.E.. Even after the inception of the Hellenistic period (323 B.C.E.), Greek and Roman authors, commenting on the beliefs of their new vassals, have much to say about the beliefs and practices surrounding the cult of Apis. In particular, they were intrigued by such issues as the marks by which the black bull-calf was recognized, the manner of his conception by a ray from heaven, his house at Memphis with court for disporting himself, the mode of prognostication from his actions, the public mourning that accompanied his death, his costly burial and the rejoicings throughout the country when a new Apis was found.<ref>These practices are commented upon by various classical writers, including [[Herodotus]] and [[Plutarch]]. Wilkinson, 172; Pinch, 106.</ref> The continued veneration of the bull god is strongly attested to by the [[Rosetta Stone]], a self-promoting text commissioned by Ptolemy V in 196 B.C.E. In it, the pharaoh uses his support of the Apis cult as a general yardstick representing his piety: | |

| + | :[Ptolemy V] [hath provided] everything in great abundance for the house wherein dwelleth the LIVING APIS; and His Majesty hath decorated it with perfect and new ornamentations of the most beautiful character always; and he hath made the LIVING APIS to rise [like the sun], and hath founded temples, and shrines, and chapels [in his honor]; [and he hath repaired the shrines, which needed repairs, and in all matters appertaining to the service of the gods.<ref>''The Rosetta Stone,'' translated by Budge (1893), accessed online at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/trs/trs07.htm sacred-texts.com]. Retrieved July 22, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Serapis: From Bull to Man=== | |

| + | {{main|Serapis}} | ||

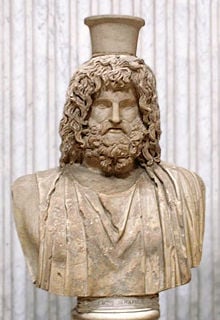

| + | [[Image:Serapis vatican.jpg|thumb|220px|right|Bust of the Hellenistic-Egyptian god ''Serapis,'' Roman copy of an original by Bryaxis which stood at the Serapeion of [[Alexandria]], Vatican Museums]] | ||

| − | + | Under [[Ptolemy I of Egypt|Ptolemy Soter]], the first non-Egyptian pharaoh, efforts were made to integrate the indigenous religion with that of their [[Hellenic]] regents. Given this motivation, Ptolemy's goal was to find a deity that could be revered by both groups as a means of providing additional stability to his reign. Since the Greeks had little respect for animal-headed figures, a Greek statue was chosen as the idol, and proclaimed to be an anthropomorphic equivalent of the highly popular Apis. This syncretic deity was named ''Aser-hapi'' (i.e., ''Osiris-Apis,'' Hellenized as ''Serapis''), and was said to be Osiris in full, rather than just his Ka. This figure's appeal to the Egyptian Hellenes was that Osiris and the Greek god [[Hades]] were considered to be equivalent, as both were chthonic deities tasked with administrating the afterlife. In this way, the figure provided a mythological and theological bridge between the two cultures. | |

| − | + | Incorporating Osiris's wife, [[Isis]], and their son [[Horus]] (in the form of ''Harpocrates''), the cult of Serapis won an important place in classical Greek religion, eventually being propagated as far as Ancient Rome. The great syncretic faith survived until 385 C.E., when Christian fundamentalists destroyed the Serapeum of Alexandria and forbade all further expressions of the cult under the decree of the [[Theodosius I]].<ref>E. A. Wallis Budge. ''The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology.'' (A Study in Two Volumes.) (New York: Dover Publications, 1969), 195-201; Dunand, 214-221; Byron E. Shafer(editor). ''Temples of ancient Egypt.'' (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997), 315 ff 170.</ref> | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | <references /> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

*{{1911}} | *{{1911}} | ||

| − | *[[ | + | * Assmann, Jan. ''In search for God in ancient Egypt.'' Translated by David Lorton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293. |

| − | *[[ | + | * Breasted, James Henry. ''Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt.'' Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454. |

| − | *[ | + | * Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). ''The Egyptian Book of the Dead.'' 1895. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ebod/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. |

| − | *Mariette | + | * __________. ''The Egyptian Heaven and Hell.'' 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com]. |

| + | * __________. ''The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology.'' A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969. | ||

| + | * __________. ''Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts.'' 1912. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/leg/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * __________. ''The Rosetta Stone.'' 1893, 1905. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/trs/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Dennis, James Teackle (translator). ''The Burden of Isis.'' 1910. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/boi/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Dunand, Françoise and Christiane Zivie-Coche. ''Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.'' Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X. | ||

| + | * Erman, Adolf. ''A handbook of Egyptian religion.'' Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907. | ||

| + | * Frankfort, Henri. ''Ancient Egyptian Religion.'' New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772. | ||

| + | * Griffith, F. Ll. and Thompson, Herbert (translators). ''The Leyden Papyrus.'' 1904. Accessed at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/dmp/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Jones, Michael. "The Temple of Apis in Memphis." ''The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology'' Vol. 76 (1990): 141-147. | ||

| + | * Larson, Martin A. ''The Story of Christian Origins.'' 1977. ISBN 0883310902. | ||

| + | * Mariette, Auguste and Maspero, Gaston. ''Le Sérapéum de Memphis.'' Paris: F. Vieweg, 1892. | ||

| + | * Meeks, Dimitri and Meeks-Favard, Christine. ''Daily life of the Egyptian gods.'' Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158. | ||

| + | * Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). ''The Pyramid Texts.'' 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | *Peck, Harry Thurston. ''Harper's Dictionary of Classical Antiquities.'' New York: Harper and Brothers, 1898. Accessible online at: [http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/efts/PERSEUS/Reference/harpers.html Perseus Digital Library]. Retrieved July 14, 2007. | ||

| + | * Pinch, Geraldine. ''Handbook of Egyptian mythology.'' Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428. | ||

| + | * Shafer, Byron E. (editor). ''Temples of ancient Egypt.'' Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991. | ||

| + | * Wilkinson, Richard H. ''The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt.'' London: Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051208. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved August 11, 2023. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[http://www.virtual-egyptian-museum.org/Collection/FullVisit/Collection.FullVisit-JFR.html?../Content/MET.LL.00887.html&0 The Virtual Egyptian Museum: Apis] | *[http://www.virtual-egyptian-museum.org/Collection/FullVisit/Collection.FullVisit-JFR.html?../Content/MET.LL.00887.html&0 The Virtual Egyptian Museum: Apis] | ||

| + | *[http://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/bullcult.html Religion in Ancient Egypt: Bull Cults] | ||

| − | |||

[[Category:Religion]] | [[Category:Religion]] | ||

| − | [[Category:Philosophy and | + | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] |

{{credit|141888575}} | {{credit|141888575}} | ||

Latest revision as of 06:01, 11 August 2023

In Ancient Egypt, Apis or Hapis (alternatively spelt Hapi-ankh) was a bull-deity worshiped in the Memphis region and thought to represent rulership and masculine vigor. Though originally a local deity, his popularity grew throughout the dynastic history, such that, by the Ptolemaic period, he was "a kind of national mascot."[1] The worship of Apis was certainly the most popular of the three great bull cults of ancient Egypt (the others being the bulls Mnevis and Buchis.)

Though Hape (Apis) is named on some of the earliest monuments in ancient Egypt, the most detailed accounts of his cult can be traced back to the New Kingdom period (1570–1070 B.C.E.). He was originally seen as "the renewal of the life" of the Memphite god Ptah, but after death he became Osorapis, (the Osiris Apis).[2]. Under the Ptolemaic dynasty, this deity became Serapis, a Hellenistic syncretism between the popular Egyptian cult and the iconography (and characterization) of the Greek god, Hades.

Apis in an Egyptian Context

| Apis in hieroglyphs | |||||||||||

or

or

or

|

As an Egyptian deity, Apis belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system developed in the Nile river basin from earliest prehistory to 525 B.C.E.[3] Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.[4] The cults within this framework, whose beliefs comprise the myths we have before us, were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.[5] Despite this apparently unlimited diversity, however, the gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “the Egyptian gods are imperfect as individuals. If we compare two of them … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”[6] One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanental—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.[7] Thus, those who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Also, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e., the cult of Amun-Re, which unified the domains of Amun and Re), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.[8]

The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely appropriate to (and defined by) the geographical and calendrical realities of its believer’s lives. Unlike the beliefs of the Hebrews, Mesopotamians and others within their cultural sphere, the Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.[9] The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was ultimately defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.[10] Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tended to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead, with a particular focus on the relationship between the gods and their human constituents.

Given that Apis (as deity) was actually understood to be the sacred bull, his cult presents another permutation of the highly concrete and immanental understanding of theology common in Ancient Egypt.

Mythological Accounts and Religious Manifestations

The cult of the Apis bull is one of the most archaic in the Egyptian religious system, hearkening back to the earliest epoch of their dynastic history. From the outset, it appears that he was a fertility god connected to grain and the herds. However, his most important affiliation was with the pharaoh, as he was seen to symbolize the king’s courageous heart, great strength, virility, and fighting spirit. This association is borne out in religious iconography, as the bull god was occasionally depicted with the sun-disk between his horns—a clear reference to Ra, the divine ruler par excellence.[11] Further, the Apis bull is unique in their iconographic system in that he is the only Egyptian god represented solely as an animal, and never as a human with an animal's head. This is likely because the physical bull, that dwelt in an enclosure at the temple in Memphis, was literally seen to be the god.[12] In this way, Apis is more strongly affiliated with the particulars of his animal existence than are the other deities in pantheon, who are merely represented by their animal forms (i.e., Horus and the falcon, Bast and the cat, Sebek and the crocodile, Thoth and the ibis).[13]

The Herald of Ptah

In the original Memphite cult, Apis was conceived as Herald of Ptah, the chief god of the area. However, the specifics of the relationship between the two deities was complex: "Ptah was never depicted as a bull or believed to be incarnate in a bull; but the Apis bull was called 'the living Apis, the herald of Ptah, who carries the truth upwards to him of the lovely face (Ptah).'" [14] This divine bovine, as a herald/manifestation of the god, was understood to be unique, in that there was only ever one Apis bull at a given time.

These beliefs were complemented by a complex system of practices depicting the proper selection and veneration of the Bull of Ptah. Since the bovines in the region where Ptah was worshiped exhibited white patterning on their mainly black bodies, a system of beliefs developed concerning which types of markings a potential Apis bull required in order to be suitable to its role. Specifically, it was required to have a white triangle on its forehead, a white vulture wing outline on its back, a scarab-shaped lump under its tongue, a white crescent moon shape on its right flank, and double hairs on its tail.[15] A bull that matched these markings was selected from the herd, brought to a temple, given a harem of cows, and worshiped as a manifestation of the craftsman god. His mother, who was believed to have conceived her divine offspring after being impregnated by a beam of light from the heavens, was also revered. At the temple, Apis was used as an oracle, his movements being interpreted as prophecies. His breath was also believed to cure disease, and his presence was thought to bless those around with virility. As a result, the temples were constructed with a window that would allow the public to bask in his holy proximity. Further, this spiritual good was made available to the populace as a whole on certain festival days, when the god would be led through the streets of the city, bedecked with jewelry and flowers. Upon the animal's death, it would be mourned, mummified, and celebrated, after which point the new Apis would be found. These funerary elements came to be important components of the god's cult around the time of the conflation of Osiris with Ptah, a development that also led to a redefinition of the bovine god (as described below).[16]

Ka of Osiris

When Osiris absorbed the identity of Ptah, becoming Ptah-Seker-Osiris, the Apis bull became seen as an aspect of Osiris rather than Ptah. Since Osiris was lord of the dead, Apis then became known as the living deceased one, whose cultic significance only increased with the death of his current incarnation. As he now represented Osiris, when the Apis bull reached the age of twenty-eight, the age when Osiris was said to have been killed by Set, symbolic of the lunar month, and the new moon, the bull was put to death with great ceremony.[17] There is evidence that parts of the body of the Apis bull were eaten by the pharaoh and his priests to absorb the bull god's great strength. As a form of Osiris, lord of the dead, it was believed that to be under the protection of the Apis bull would give the person control over the four winds in the afterlife.[18]

By the New Kingdom, the remains of the Apis bulls were interred at the cemetery of Saqqara. The earliest known burial in Saqqara was performed in the reign of Amenhotep III (1391–1353 B.C.E.) by his son Thutmosis; afterwards, seven more bulls were buried nearby. Ramesses II initiated Apis burials in what is now known as the Serapeum, an underground complex of burial chambers at Saqqara for the sacred bulls, a site used through the rest of Egyptian history into the reign of Cleopatra VII.[19]

Unlike the cults of most of the other Egyptian deities, the worship of the Apis bull was continued by the Greeks and after them by the Romans, and lasted until almost 400 C.E. Even after the inception of the Hellenistic period (323 B.C.E.), Greek and Roman authors, commenting on the beliefs of their new vassals, have much to say about the beliefs and practices surrounding the cult of Apis. In particular, they were intrigued by such issues as the marks by which the black bull-calf was recognized, the manner of his conception by a ray from heaven, his house at Memphis with court for disporting himself, the mode of prognostication from his actions, the public mourning that accompanied his death, his costly burial and the rejoicings throughout the country when a new Apis was found.[20] The continued veneration of the bull god is strongly attested to by the Rosetta Stone, a self-promoting text commissioned by Ptolemy V in 196 B.C.E. In it, the pharaoh uses his support of the Apis cult as a general yardstick representing his piety:

- [Ptolemy V] [hath provided] everything in great abundance for the house wherein dwelleth the LIVING APIS; and His Majesty hath decorated it with perfect and new ornamentations of the most beautiful character always; and he hath made the LIVING APIS to rise [like the sun], and hath founded temples, and shrines, and chapels [in his honor]; [and he hath repaired the shrines, which needed repairs, and in all matters appertaining to the service of the gods.[21]

Serapis: From Bull to Man

Under Ptolemy Soter, the first non-Egyptian pharaoh, efforts were made to integrate the indigenous religion with that of their Hellenic regents. Given this motivation, Ptolemy's goal was to find a deity that could be revered by both groups as a means of providing additional stability to his reign. Since the Greeks had little respect for animal-headed figures, a Greek statue was chosen as the idol, and proclaimed to be an anthropomorphic equivalent of the highly popular Apis. This syncretic deity was named Aser-hapi (i.e., Osiris-Apis, Hellenized as Serapis), and was said to be Osiris in full, rather than just his Ka. This figure's appeal to the Egyptian Hellenes was that Osiris and the Greek god Hades were considered to be equivalent, as both were chthonic deities tasked with administrating the afterlife. In this way, the figure provided a mythological and theological bridge between the two cultures.

Incorporating Osiris's wife, Isis, and their son Horus (in the form of Harpocrates), the cult of Serapis won an important place in classical Greek religion, eventually being propagated as far as Ancient Rome. The great syncretic faith survived until 385 C.E., when Christian fundamentalists destroyed the Serapeum of Alexandria and forbade all further expressions of the cult under the decree of the Theodosius I.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Geraldine Pinch, Handbook of Egyptian mythology. (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002), 105.

- ↑ In this form, he was assimilated into Osiris, a process that was also understood to occur with the spirits of dead humans.

- ↑ This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Adolf Erman. A handbook of Egyptian religion, Translated by A. S. Griffith. (London: Archibald Constable, 1907), 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.

- ↑ The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).

- ↑ These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Dimitri Meeks and Christine Meeks-Favard. Daily life of the Egyptian gods, Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996), 34-37).

- ↑ Henri Frankfort. Ancient Egyptian Religion. (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961), 25-26.

- ↑ Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.

- ↑ Frankfort, 20-21.

- ↑ Jan Assmann. In search for God in ancient Egypt, Translated by David Lorton. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (James Henry Breasted. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986), 8, 22-24).

- ↑ Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.

- ↑ However, this iconographic flourish is of a comparatively later date, as Ra had initially been associated with the Mnevis bull. Frankfort, 10; Wilkinson, 171.

- ↑ However, this identity only applied to the specific animal, which was recognized by various physiognomic features, not to the species as a whole. Budge (1969), Vol. I, 27; Frankfort, 10.

- ↑ Budge (1969), Vol. II, 195-197; Meeks and Favard-Meeks, 136-138; Frankfort, 10.

- ↑ Frankfort, 10.

- ↑ Richard H. Wilkinson. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 171.

- ↑ When excavating the Serapeum (Temple of Apis) at Memphis, Mariette revealed the tombs of over sixty animals, ranging from the time of Amenophis III (1391–1353 B.C.E.) to the Ptolemaic dynasty (305-330 B.C.E.). Steles describing the regnal dates of the animals, often including the names of their mother cows and their places of birth, were also found at many of these sites. Meeks and Favard-Meeks, 136-140; Françoise Dunand and Christiane Zivie-Coche. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E., Translated from the French by David Lorton. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004), 306; Jones, passim. See also: Serapeum at aldokkan.com, retrieved July 22, 2007.

- ↑ Wilkinson, 172.

- ↑ Wilkinson, 170-172; Meeks and Favard-Meeks, 138-139.

- ↑ Meeks and Favard-Meeks, 136-140; Dunand, 306; Michael Jones, "The Temple of Apis in Memphis," The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 76 (1990): 141-147, passim; Dunand, 331, 333. See also: Serapeum at aldokkan.com, retrieved July 22, 2007.

- ↑ These practices are commented upon by various classical writers, including Herodotus and Plutarch. Wilkinson, 172; Pinch, 106.

- ↑ The Rosetta Stone, translated by Budge (1893), accessed online at sacred-texts.com. Retrieved July 22, 2007.

- ↑ E. A. Wallis Budge. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. (A Study in Two Volumes.) (New York: Dover Publications, 1969), 195-201; Dunand, 214-221; Byron E. Shafer(editor). Temples of ancient Egypt. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997), 315 ff 170.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Assmann, Jan. In search for God in ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293.

- Breasted, James Henry. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Book of the Dead. 1895. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- __________. The Egyptian Heaven and Hell. 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com].

- __________. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.

- __________. Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts. 1912. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- __________. The Rosetta Stone. 1893, 1905. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dennis, James Teackle (translator). The Burden of Isis. 1910. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dunand, Françoise and Christiane Zivie-Coche. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E. Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X.

- Erman, Adolf. A handbook of Egyptian religion. Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907.

- Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772.

- Griffith, F. Ll. and Thompson, Herbert (translators). The Leyden Papyrus. 1904. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Jones, Michael. "The Temple of Apis in Memphis." The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Vol. 76 (1990): 141-147.

- Larson, Martin A. The Story of Christian Origins. 1977. ISBN 0883310902.

- Mariette, Auguste and Maspero, Gaston. Le Sérapéum de Memphis. Paris: F. Vieweg, 1892.

- Meeks, Dimitri and Meeks-Favard, Christine. Daily life of the Egyptian gods. Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158.

- Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). The Pyramid Texts. 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Peck, Harry Thurston. Harper's Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1898. Accessible online at: Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved July 14, 2007.

- Pinch, Geraldine. Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428.

- Shafer, Byron E. (editor). Temples of ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051208.

External links

All links retrieved August 11, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.