Difference between revisions of "Anglo-Asante Wars" - New World Encyclopedia

(submitted - images ok) |

|||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

[[Image:Asantewaa.jpg|thumb|Queen Yaa Asantewaa, herorine of the Asante revolt of 1900.]] | [[Image:Asantewaa.jpg|thumb|Queen Yaa Asantewaa, herorine of the Asante revolt of 1900.]] | ||

In the [[War of the Golden Stool]] (1900), the remaining Asante court not exiled to the Seychelles mounted an offensive against the British Residents at the Kumasi Fort, but were defeated. [[Yaa Asantewaa]] (1840-1921), the Queen-Mother of Ejisu and other Asante leaders were also sent to the Seychelles. The revolt was provoked by a British captain who had been commissioned to find the location of the "Golden Stool" (the symbol of the king's authority) and beat women and children to compel them to reveal its whereabouts so that Sir Frederick Hodgson, the Governor, could sit on it.<ref>"History of Golden Stool," Ghana Web [http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/history/golden_stool.php History of golden Stool]. The stool was kept in a secret location. Not even the king was allowed to sit on this sacred object. It was accidentally discovered by railroad workers in 1920, who stripped off its gold ornaments. Retrieved May 16, 2008.</ref> The role played by Yaa Asantewaa has been debated; was her leadership symbolic, or was she the principal leader of the revolt, which for "three months laid siege to the British mission at the fort of Kumasia" before the British brought in reinforcements? After breaking the siege, the "the British troops plundered the villages, killed much of the population, confiscated their lands and left the remaining population dependent upon the British for survival."<ref>Bois, Danuta. 1998. "Yaa Asantewaa." Distinguishe Women of Past and Present [http://www.distinguishedwomen.com/biographies/yaa-asantewaa.html Yaa Asantewaa] Retrieved May 16, 2008. See Boahen, A. Adu on whether her leadership was military or symbolic.</ref> The Ashanti territories became part of the [[Gold Coast (British colony)|Gold Coast]] colony on 1 January 1902. | In the [[War of the Golden Stool]] (1900), the remaining Asante court not exiled to the Seychelles mounted an offensive against the British Residents at the Kumasi Fort, but were defeated. [[Yaa Asantewaa]] (1840-1921), the Queen-Mother of Ejisu and other Asante leaders were also sent to the Seychelles. The revolt was provoked by a British captain who had been commissioned to find the location of the "Golden Stool" (the symbol of the king's authority) and beat women and children to compel them to reveal its whereabouts so that Sir Frederick Hodgson, the Governor, could sit on it.<ref>"History of Golden Stool," Ghana Web [http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/history/golden_stool.php History of golden Stool]. The stool was kept in a secret location. Not even the king was allowed to sit on this sacred object. It was accidentally discovered by railroad workers in 1920, who stripped off its gold ornaments. Retrieved May 16, 2008.</ref> The role played by Yaa Asantewaa has been debated; was her leadership symbolic, or was she the principal leader of the revolt, which for "three months laid siege to the British mission at the fort of Kumasia" before the British brought in reinforcements? After breaking the siege, the "the British troops plundered the villages, killed much of the population, confiscated their lands and left the remaining population dependent upon the British for survival."<ref>Bois, Danuta. 1998. "Yaa Asantewaa." Distinguishe Women of Past and Present [http://www.distinguishedwomen.com/biographies/yaa-asantewaa.html Yaa Asantewaa] Retrieved May 16, 2008. See Boahen, A. Adu on whether her leadership was military or symbolic.</ref> The Ashanti territories became part of the [[Gold Coast (British colony)|Gold Coast]] colony on 1 January 1902. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although mainly ceremonial, the office of Asantehene did continue, after a lapse during Premeh's exile. He was allowed to return to the Gold Coast in 1926. The British did not, however, let him use the title of Asantehene (he was permiited to use the subordinate title, Kumasehene, ruler of Kumasi) but in 1935, the title was revived. As an ancient office of clan leadership, the title is recognized by the Constitution of Ghana. In 1999, King Otumfuo Osei Tutu II became the the 16th Asantehene, King of the Ashanti. He is a direct descendant of Otumfuo Osei Tutu I. Whether the way in which the British dealt with the Asante was just or fair may now be academic, given the passage of time. On the other hand, their inability to see much if anything of value in African societies did not predispose them to refrain from territorial acquisition at the expense of indigenous polities. The only polity to survive the [[Scramble for Africa]] in the nineteenth century was the [[Ethiopian Empire]]. | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 00:40, 22 May 2008

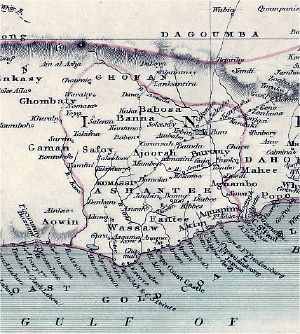

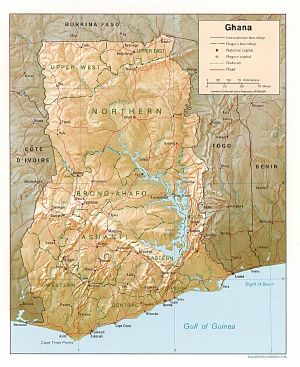

The Anglo-Asante Wars were conflicts (four) between the Asante Union in the Akan interior of what is now Ghana and the British Empire in the 19th century. The ruler of the Asante (or Ashanti) was the Ashantehene (King of all Ashanti). The coastal people, primarily Fante and the inhabitants of Accra, who were chiefly Ga, came to rely on British protection against Ashanti incursions. Finally the Asante Empire becoming a British protectorate. Having ended slavery on the Gold Coast in 1806 (which was followed by a ban in all British colonies in 1833), the British, who had previously engaged in the slave trade with the Asante, now wanted to exploit the natural resources of the area, and regarded the Asante, who dominated trade, as an obstacle. Legendary for their wealth in gold, the Ashante controlled its mining and distribution in the interior. Adopting a moralizing approach towards the Asate due to their continued practice of slavery, the British set out to crush their power and to dismantle their state under British rule. The first war (1823 and 1831), which followed earlier skirmishes in 1806-7, 1811 and 1814-16, saw the British suffer a defeat. This war was seen by the British as part of their anti-slavery campaign. The second war, 1863-64, ended in a stalemate. By 1874, when the third war ended in a peace-treaty, the British had proclaimed the rest of the Gold Coast as a Crown Colony, with Accra as its capital from 1877. The fourth war, 1894-96, ended in a British victory. The Asante were forced to sign a treaty of protection; the Ashantehene, with other leaders, was exiled. After a failed revolt in 1900, led by Yaa Asantewaa, the Queen-Mother, Asante territory was finally annexed as part of the Crown Colony. It had taken almost a century, however, from the earliest conflict of 1806-7 for the colonial power to defeat what was a sophisticated, well organized African state. That state had also possessed many consultative and democratic features, since the Ashantehene shared power with others; he was also ultimately answerable to his subjects for his leadership of the state. This system was replaced by the more or less absolute rule of the British Empire’s colonial officers, who were answerable to a government thousands of miles away, not to the people over whom they had authority.

Earlier wars

The British had been involved in three earlier skirmishes:

In the Ashanti-Fante War of 1806-07, the British refused to hand over two rebels pursued by the Asante, but eventually handed one over (the other escaped).

In the Ga-Fante War of 1811, the Akwapim captured a British fort at Tantamkweri and a Dutch fort at Apam.

In the Ashanti-Akim-Akwapim War of 1814-16 the Ashanti defeated the Akim-Akwapim alliance. Local British, Dutch, and Danish authorities all had to come to terms with the Ashanti. In 1817 the (British) African Company of Merchants signed a treaty of friendship that recognized Ashanti claims to sovereignty over much of the coast.

First Anglo-Asante War

The First Anglo-Asante War was from 1823 to 1831. In 1823 Sir Charles MacCarthy, rejecting Ashanti claims to Fanti areas of the coast and resisting overtures by the Ashanti to negotiate, led an invading force from the Cape Coast. The British had allied themselves with the Fenti partly because this enabled access to the coast, essential for trade but also because the Ashante had good relations with their commercial rivals, the Dutch. He was defeated and killed by the Ashanti, and the heads of MacCarthy and Ensign Wetherall were kept as trophies. See Charles MacCarthy for details of the Battle of Nsamankow, when MacCarthy's troops (who had not joined up with the other columns) were overrun. Major Alexander Gordon Laing, the explorer who, later, would reach Timbuktu but die on his journey home, returned to Britain with news of their fate.

The Ashanti swept down to the coast, but disease forced them back. The Ashanti were so successful in subsequent fighting that in 1826 they again moved on the coast. At first they fought very impressively in an open battle against superior numbers of British allied forces, including Denkyirans. However, the novelty of British rockets caused the Ashanti army to withdraw. [1] In 1831, the Pra River was accepted as the border in a treaty, and there was thirty years of peace.

Second Anglo-Asante War

The Second Anglo-Asante War was from 1863 to 1864. With the exception of a few minor Ashanti skirmishes across the Pra in 1853 and 1854, the peace between Asanteman and the British Empire had remained unbroken for over 30 years. Then, in 1863, a large Ashanti delegation crossed the river pursuing a fugitive, Kwesi Gyana. There was fighting, with casualties on both sides, but the governor's request for troops from England was declined and sickness forced the withdrawal of his West Indian troops, with both sides losing more men to sickness than any other factor, and in 1864 the war ended in a stalemate.

Third Anglo-Asante War

The Third Anglo-Asante War lasted from 1873 to 1874. In 1869 a German missionary family and a Swiss missionary had been taken to Kumasi. They were hospitably treated, but a ransom was required for them. In 1871 Britain purchased the Dutch Gold Coast from the Dutch, including Elmina which was claimed by the Ashanti. The Ashanti invaded the new British protectorate.

General Wolseley, then a colonel, with 2,500 British troops and several thousand West Indian and African troops (including some Fante) was sent against the Ashanti, and subsequently became a household name in Britain. The war was covered by war correspondents, including Henry Morton Stanley and G. A. Henty. Military and medical instructions were printed for the troops. [2] The British government refused appeals to interfere with British armaments manufacturers who sold to both sides.[3]

Wolseley went to the Gold Coast in 1873, and made his plans before the arrival of his troops in January 1874. He fought the Battle of Amoaful on January 31 of that year, and, after five days' fighting, ended with the Battle of Ordahsu. The capital, Kumasi, which was abandoned by the Ashanti was briefly occupied by the British and burned. The British were impressed by the size of the palace and the scope of its contents, including "rows of books in many languages." [4] [5] The Ashantehene, the ruler of the Ashanti (Asente) signed a harsh British treaty, the Treaty of Fomena in July 1874, to end the war. Wolseley completed the campaign in two months, and re-embarked his troops for home before the unhealthy season began. Most of the 300 British casualties were from disease. Wolseley left behind a power vacuum which led to more fighting, as the Ashantehene could no longer control the former vassal tribes. He became one of the most decorated and celebrated men in Britain. He was promoted to Major General, elevated to a higher rank of knighthood, made a Freeman of the City of London, awarded 25,000 pounds by Parliament and given honorary doctorates by Oxford and Cambrudge.

Fourth Anglo-Asante War

The Fourth Anglo-Asante War was a brief war, from 1894. The Ashanti turned down an unofficial offer to become a British protectorate in 1891, extending to 1894. Wanting to keep French and German forces out of Ashanti territory (and its gold), the British were anxious to conquer Asanteman once and for all. The war started on the pretext of failure to pay the fines levied on the Asante monarch by the Treaty of Fomena after the 1874 war.

Sir Francis Scott left Cape Coast with the main expedition force of British and West Indian troops in December 1895, and arrived in Kumasi in January 1896. The Asantehene directed the Ashanti to not resist. Soon Governor William Maxwell arrived in Kumasi as well. Robert Baden-Powell led a native levy of several local tribes in the campaign. Asantehene Agyeman Prempeh was arrested and deposed. He was forced to sign a treaty of protection, and with other Asante leaders was sent into exile in the Seychelles.

War of the Golden Stool

In the War of the Golden Stool (1900), the remaining Asante court not exiled to the Seychelles mounted an offensive against the British Residents at the Kumasi Fort, but were defeated. Yaa Asantewaa (1840-1921), the Queen-Mother of Ejisu and other Asante leaders were also sent to the Seychelles. The revolt was provoked by a British captain who had been commissioned to find the location of the "Golden Stool" (the symbol of the king's authority) and beat women and children to compel them to reveal its whereabouts so that Sir Frederick Hodgson, the Governor, could sit on it.[6] The role played by Yaa Asantewaa has been debated; was her leadership symbolic, or was she the principal leader of the revolt, which for "three months laid siege to the British mission at the fort of Kumasia" before the British brought in reinforcements? After breaking the siege, the "the British troops plundered the villages, killed much of the population, confiscated their lands and left the remaining population dependent upon the British for survival."[7] The Ashanti territories became part of the Gold Coast colony on 1 January 1902.

Although mainly ceremonial, the office of Asantehene did continue, after a lapse during Premeh's exile. He was allowed to return to the Gold Coast in 1926. The British did not, however, let him use the title of Asantehene (he was permiited to use the subordinate title, Kumasehene, ruler of Kumasi) but in 1935, the title was revived. As an ancient office of clan leadership, the title is recognized by the Constitution of Ghana. In 1999, King Otumfuo Osei Tutu II became the the 16th Asantehene, King of the Ashanti. He is a direct descendant of Otumfuo Osei Tutu I. Whether the way in which the British dealt with the Asante was just or fair may now be academic, given the passage of time. On the other hand, their inability to see much if anything of value in African societies did not predispose them to refrain from territorial acquisition at the expense of indigenous polities. The only polity to survive the Scramble for Africa in the nineteenth century was the Ethiopian Empire.

See also

- Asante Union

- British Empire

- Ghana

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Lloyd, Alan, pp. 39-53

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 88-102

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 83

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 172-174

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 175

- ↑ "History of Golden Stool," Ghana Web History of golden Stool. The stool was kept in a secret location. Not even the king was allowed to sit on this sacred object. It was accidentally discovered by railroad workers in 1920, who stripped off its gold ornaments. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ↑ Bois, Danuta. 1998. "Yaa Asantewaa." Distinguishe Women of Past and Present Yaa Asantewaa Retrieved May 16, 2008. See Boahen, A. Adu on whether her leadership was military or symbolic.

Bibliography

- Agbodeka, Francis. 1971. African Politics and British Policy in the Gold Coast, 1868–1900: A Study in the Forms and Force of Protest. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0810103680.

- Agyeman-Duah, Ivor, and Abdulai Awudu. 2001. Yaa Asantewaa the exile of King Prempeh and the heroism of an African queen. Ghana: Centre for Intellectual Renewal ISBN 9789988812034

- Boahen, A. Adu. 2000. "Yaa Asantewaa in the Yaa Asantewa War of 1900: military leader or symbolic head?" Ghana Studies. 3: 111-135.

- Edgerton, Robert B. 1995. The fall of the Asante Empire: the hundred-year war for Africa's Gold Coast. New York: The Free Press ISBN 9780029089262

- Lloyd, Alam. 1964. The drums of Kumasi: the story of the Ashanti wars. London: Longmans.

- McCarthy, Mary. 1983. Social Change and the Growth of British Power in the Gold Coast: The Fante States, 1807–1874. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 0819131482.

- Wilks, Ivor. 1975. Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521204631.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.