Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (July, 1591 – August 20, 1643) was the unauthorized Puritan preacher of a dissident church discussion group and a pioneer settler in Rhode Island and the Bronx.

Early years

Anne Hutchinson was born Anne Marbury on July 17, 1591 in Alford, Lincolnshire, England. She was the eldest daughter of Francis Marbury (1555-1611), a clergyman educated at Cambridge and Puritan reformer, and Bridget Dryden (1563-1645).

In 1605, she moved with her family from Alford to London. At the age of 21, she married William Hutchinson, a prosperous cloth merchant. Anne and William returned to Alford. Anne and William Hutchinson considered themselves to be part of the Puritan movement, and in particular, they followed the teachings of the Reverend John Cotton, their religious mentor.

Migration to the New World

Puritans, just like other non-Anglican sects, were being forced to pay taxes to the Crown in England and they began to migrate to America for greater financial freedoms. Hutchinson emigrated from England to Massachusetts in 1634 without John Cotton's approval. She, her husband and ten of their children sailed to America on the Griffon. Anne Hutchinson lost a total of four children in early childhood, one of whom was born in America.

Religious activities

Anne Hutchinson's conflict with the colony's Puritan religious establishment began with a series of Bible-study classes. Hutchinson invited her friends and neighbors — women, at first — to discuss in her home the literal words of the Bible. She may have also discussed the teachings of charismatic local minister, the Reverend John Cotton, according to one historian although other sources suggest that the colony had banished the Reverend Cotton around the time of her arrival in Massachusetts.

At some point in her teachings, Hutchinson moved beyond straight-forward discussions of Biblical texts and into the more controversial practice of commenting on teachings from the pulpit of the established religious hierarchy, specifically the Reverend John Wilson. As word of her teachings spread, she accrued new followers, among them men like Sir Henry Vane, who would become the governor of the colony in 1636. Contemporary reports suggest that upwards of eighty people attended her home Bible study sessions. Officially sanctioned sermons may or may not have had more regular attendance. Peters, Vane and John Cotton may have attempted, according to some historical accounts, to have Reverend Wilson replaced with Anne's brother-in-law, John Wheelwright. In 1637, Vane lost the governorship to John Winthrop, who did not share Vane's opinion of Hutchinson. He instead "considered her a threat to his 'city set on a hill'," according to Gomes, and described her meetings as being a "thing not tolerable nor comely in the sight of God, nor fitting for [her] sex."

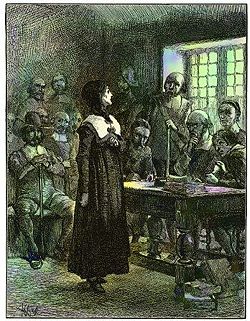

Hutchinson publicly justified her comments on pulpit teachings, against contemporary religious mores, as being authorized by 'an inner spiritual truth'. Governor Winthrop and the established religious hierarchy considered her comments to be heretical, i.e. unfounded criticism of the clergy from an unauthorized source. In March 1638, the community voted to excommunicate her from the Massachusetts Bay Colony church for dissenting the Puritan orthodoxy. They accused Hutchinson of blasphemy and of lewd conduct. She was put on trial, found guilty and eventually banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

She and several dozen followers relocated to Rhode Island and then later to Long Island Sound where she and seven of her children were scalped during a Siwanoy tribe attack on their settlement. She was killed by Indians at what is now Pelham Bay Park, New York on August 31, 1643[1]. One of her children, Susanna Hutchinson, was taken by the Native Americans, but was ransomed back after four years. Also, the other four of her children had remained in Rhode Island when she moved to New Netherland.

Anne Hutchinson's religious beliefs

"As I understand it, laws, commands, rules and edicts are for those who have not the light which makes plain the pathway. He who has God's grace in his heart cannot go astray." ---Anne Hutchinson

During her trial, which she walked to while being five months pregnant, Hutchinson testified about her own personal closeness with God. This apparently led some Puritan leaders to consider her arrogant. She went so far as to say that God gave her direct personal messages, a statement unusual enough at the time to make even John Cotton, her longtime supporter, uncertain about whether he should remain allied with her. She also surprised many people by dismissing the idea of "Original Sin". She was once quoted as saying, essentially, that one couldn't look into the eyes of a child and see sin therein.

Hutchinson emphasized the belief that salvation was by faith alone, which is a typical Protestant belief. Although this doctrine was accepted and taught by Puritans, it was not very compatible with the authoritarian, theocratic system that the Puritan leaders favored, as it tended to make the individual feel that he could take control of his own spiritual life and his own relationship with God. She and her followers began to be called Antinomians because of this emphasis on faith rather than obedience to the ethical instructions of the Bible.

She held to predestination, but preached that it implied good works were futile, and restricting one's behavior was arrogant. She also argued that many of the clergy were not among the "elect", and entitled to no spiritual authority. She challenged assumptions about the proper role of women in Puritan society, and eventually began to attack the clergy openly.

Ditmore's reexamination of Hutchinson's 1637 "Immediate Revelation" confession, particularly its biblical allusions, provides a deeper understanding of her position and the reactions of the Massachusetts General Court. Rather than a literal revelation in the form of unmediated divine communication, the confession suggests that Hutchinson experienced her revelations through a form of Biblical divination. The Biblical references in her confession, which contain a prophecy of catastrophe and redemption, confirm the court's belief that she had transgressed the authority of the colony's ministers. These references also reveal an irreconcilable conflict over theological issues of revelation, miracles, and scripture.

Modern interpretation of events

Upheld equally as a symbol of religious freedom, liberal thinking and feminism, Anne Hutchinson is something of a contentious figure for modern audiences. A current “cause celebre”, she has been in turn lionized, mythologized and demonized by like-minded individuals. In particular, historians and other observers have interpreted and re-interpreted her life within the following frameworks:

Unauthorized influence

Historians who interpret Hutchinson's life events through the lens of the power politic, have drawn the conclusion that Hutchinson suffered more because of her growing influence rather than her radical teachings. In his article on Hutchinson in Forerunner magazine, Rogers says as much, writing that her interpretations were not "antithetical to what the puritans believed at all. What began as the quibbling over fine points of Christian doctrine ended as a confrontation over the role of authority in the colony." Hutchinson may have criticized the established religious authorities, as did others, but she did so while cultivating an energetic following.

Role of women in Puritan society

Yet Hutchinson may have been brought down sexually; other commentators have suggested that she fell victim to contemporary mores surrounding the role of women in Puritan society. Hutchinson, according to numerous reports, spoke her mind freely within the context of a male hierarchy unaccustomed to outspoken women. In addition, she welcomed men into her home, an unusual act in a Puritan society. It may also be noteworthy that Hutchinson shared the profession — midwifery — that would become a pivotal attribute of the women accused in the Salem witch trials of 1692, forty years after her death..

Political king making

One little-publicized interpretation suggests that Huchinson doomed herself by engaging in political maneuvering surrounding the leadership of her church, and therefore of the local colonial government. She found herself on the losing side of a political battle that continued long after the election was won. [citation needed]

Hutchinson's modern memorials

Some literary critics trace the character of Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter to Hutchinson's persecution in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Hawthorne might have been symbolizing Hutchinson in the trials and punishment of Prynne. It has been noted that, in the novel, the rose bush supposedly came up from the foot of Anne Hutchinson outside of the prison.

In southern New York State, the Hutchinson River, one of the very few rivers named after a woman, and the Hutchinson River Parkway are her most prominent namesakes. Elementary schools,such as in the town of Portsmouth, Rhode Island, and in the Westchester County towns of Pelham and Eastchester are other examples.

A statue of Hutchinson stands in front of the State House in Boston, Massachusetts. [1] It was erected in 1922. The inscription on the statue reads:

Anne Marbury Hutchinson was killed by Indians at Pelham Bay, Long Island Sound, in what is now the Bronx. Some say the Indians had been given leave to kill her by the Massachusetts government. In early days the area was called East Chester, but in today's terms, that invokes an incorrect location, for the town of Eastchester is reduced in size and is some 8 miles or so inland in what is now Westchester County, and Pelham is separate and in the same county at the Bronx border. Anne and 15 others, including children and servants, are buried in a mound on her West Farms property in the Bronx. One daughter, Susanna, escaped the massacre on 20 Aug 1643 and lived to report the affair. As for West Farms, it was at one time part of Westchester County. For its genesis, jump to

In 1987, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis pardoned Anne Hutchinson, in order to revoke the order of banishment by Governor Endicott, 350 years earlier.

Bibliography

- Battis, Emery. Saints and Sectaries. U North Carolina Press, 1962.

- Ditmore, Michael G. "A Prophetess in Her Own Country: an Exegesis of Anne Hutchinson's 'Immediate Revelation.'" William and Mary Quarterly 2000 57(2): 349-392. Issn: 0043-5597 Fulltext: in Jstor; The article includes an annotated transcription of Hutchinson's "Immediate Revelation."

- Gura, Philip F. A Glimpse of Sion's Glory: Puritan Radicalism in New England, 1620-1660. Wesleyan U. Press, 1984. 398 pp.

- Lang, Amy Schrager. Prophetic Woman: Anne Hutchinson and the Problem of Dissent in the Literature of New England. U. of California Pr., 1987. 237 pp.

- LaPlante, Eve "American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, The Woman Who Defied the Puritans." HarperSanFrancisco, 2004, pp. 19, 31

- Morgan, Edmund S. “The Case Against Anne Hutchinson.” New England Quarterly 10 (1937): 635-649. online at www.jstor.org

- Richardson, Douglas, "Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families." Genealogical Publishing Co., 2004, p. 493

- Williams, Selma R. Divine Rebel: The Life of Anne Marbury Hutchinson. 1981. 246 pp.

- Winship, Michael P. The Times and Trials of Anne Hutchinson: Puritans Divided. U. Press of Kansas, 2005. 180 pp.

- Winship, Michael P. Making Heretics: Militant Protestantism and Free Grace in Massachusetts, 1636-1641 (2002)

Primary sources

- Hall, David D., ed. The Antinomian Controversy, 1636-1638: A Documentary History. Second Edition. Duke University Press, 1990

- Bremer, Francis J., ed. Anne Hutchinson, Troubler of the Puritan Zion. 1980. 152 pp.

External links

- Tribute website

- Michael P. Winship, ‘Hutchinson , Anne (bap. 1591, d. 1643)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 22 Dec 2006

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.