Sebastian Franck

Sebastian Franck (c. 1499 â c. 1543) was a sixteenth-century German Protestant Reformer, theologian, freethinker, humanist, and radical reformer. Ordained as a Roman Catholic priest, he converted to Lutheranism in 1525 but became increasingly dissatisfied with Lutheran doctrines, religious dogmatism in general, and the concept of an institutional church. He gradually developed his own vision of an invisible spiritual church, universal in scope, an ideal to which he remained faithful until the end of his life. In 1531, after the publication of his major work, Chronica, Zeitbuch und Geschichtsbibel (Chronica: Time Book and Historical Bible), a wide-ranging study of Catholic heresies and heretics, Franck was imprisoned briefly by the Roman Catholic authorities and forced to leave Strassburg. In 1539 he was similarly compelled to leave Ulm by Lutheran critics.

Franck came to believe that God communicates with individuals through the portion of the divine remaining in each human being. He eventually dismissed the human institution of the church, claiming that the true church was composed of all those, regardless of their faith, who allowed the spirit of God to work with them. Franck considered the Bible to be a book full of contradictions that veiled its true message. He did not view Redemption as a historical event, and regarded doctrines such as the Fall of Man and redemption by the crucifixion of Christ as figures, or symbols, of eternal truths.

Life

Franck was born about 1499 at Donauwörth, Bavaria. He later styled himself Franck von Word because of his birthplace. Franck entered the University of Ingolstadt on March 26, 1515, and afterward went to Bethlehem College, incorporated with the university, as an institution of the Dominicans at Heidelberg. Soon after 1516, he was ordained and named a curate in the Roman Catholic diocese of Augsburg. A fellow student of the Reformer Martin Bucer at Heidelberg, Franck probably attended the Augsburg conference in October of 1518 with Martin Bucer and Martin Frecht.

In 1525 Franck gave up his curacy, joined the Lutherans at Nuremberg, and became preacher at Gustenfelden. His first work was a German translation (with additions) of the first part of the Diallage (or Conciliatio locorum Scripturae), directed against Sacramentarians and Anabaptists by Andrew Althamer, then deacon of St. Sebalds at Nuremberg. Franck was apparently disappointed by the moral results of the Reformation, and began to move away from Lutheranism. He apparently came in contact with the Anabaptist Hans Denck's disciples at Nürnberg, but soon denounced Anabaptism as dogmatic and narrow. Franck became increasingly dissatisfied with Lutheran doctrines, religious dogmatism in general, and the concept of an institutional church.

On March 17, 1528, he married a gifted lady, whose brothers, pupils of Albrecht Dürer, had got into trouble through Anabaptist tendencies. In the same year he wrote a treatise against drunkenness. In the autumn of 1529, in search of greater spiritual freedom, Franck moved to Strassburg, which was then a center for religious radicals and reformers. There he became a friend of the Reformer and mystic Kaspar Schwenckfeld, who strengthened Franck's antipathy to dogmatism. In the same year he produced a free version of the famous Supplycacyon of the Beggers, written abroad by Simon Fish. Franck, in his preface, says the original was in English; elsewhere he says it was in Latin.

To his translation (1530) of a Latin Chronicle and Description of Turkey (Turkenchronik), by a Transylvanian captive, which had been prefaced by Luther, he added an appendix holding up the Turk as in many respects an example to Christians. He also substituted, for the dogmatic restrictions of Lutheran, Zwinglian and Anabaptist sects, the vision of an invisible spiritual church, universal in scope, an ideal to which he remained faithful. In 1531 Franck published his major work, the Chronica, Zeitbuch und Geschichtsbibel (Chronica: Time Book and Historical Bible), a wide-ranging anti-Catholic study of heresies and heretics, largely compiled on the basis of the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493). Its treatment of social and religious questions reflected the attitudes of the Reformation. In it Franck exhibited a strong sympathy with "heretics," and urged fairness to all kinds of freedom of opinion. He was driven from Strassburg by the authorities, after a short imprisonment in December, 1531. He tried to make a living in 1532 as a soapboiler at Esslingen, and in 1533 moved to Ulm, where he established himself as a printer and on October 28, 1534, was admitted as a burgess.

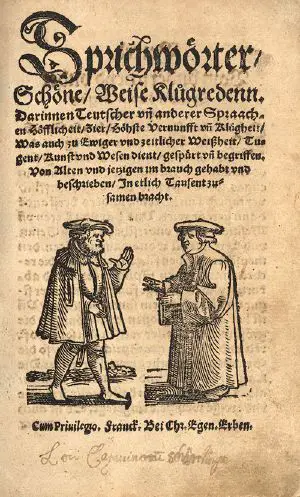

Weltbuch, a supplement to Chronica, was printed at Tubingen in 1534. Franckâs publication, in the same year, of the Paradoxa brought him trouble with the authorities, who withdrew an order for his banishment only when he promised to submit future works for censure. Not interpreting this as applying to works printed outside Ulm, in 1538 he published Guldin Arch at Augsburg, and Germaniae chronicon at Frankfort. Martin Luther had come to regard Franck as avoiding both belief and commitment, and the Lutherans compelled him to leave Ulm in January, 1539. After that time he seems to have had no settled abode. At Basel he found work as a printer, and it was probably there that he died in the winter of 1542-1543. He had published in 1539 Kriegbuchlein des Friedens, Schrifftliche und ganz grundliche Auslegung des 64 Psalms, and his Das verbutschierte mit sieben Siegein verschlossene Buch (a biblical index, exhibiting contradictions in Scripture). In 1541 he published Spruchwörter (a collection of proverbs). In 1542 he issued a new edition of his Paradoxa and some smaller works.

Thought

Franckâs openness to the religious faiths of various cultures and historical traditions, and his opposition to dogmatism, sectarianism and institutional religion mark him as one of the most modern thinkers of the sixteenth century. Franck combined the humanist's passion for freedom with the mystic's devotion to the religion of the spirit. Luther contemptuously dismissed him as a mouthpiece of the devil, and Martin Frecht of Nuremberg pursued him with bitter zeal, but even when faced with persecution from all sides, Franck never gave up his commitment to his spiritual ideal. In the last year of his life, in a public Latin letter, he exhorted his friend Johann Campanus to maintain freedom of thought in face of the charge of heresy.

Franck came to believe that God communicates with individuals through the portion of the divine remaining in each human being. He eventually dismissed the human institution of the church, and believed that theology could not properly claim to give expression to the inner word of God in the heart of the believer. God was the eternal goodness and love which are found in all men, and the true church was composed of all those who allowed the spirit of God to work with them. Franck did not view Redemption as a historical event, and regarded doctrines such as the Fall of Man and redemption by the crucifixion of Christ as figures, or symbols, of eternal truths.

Franck considered the Bible to be a book full of contradictions that veiled its true message, and had no interest in dogmatic debate. He even suggested that Christians needed to know only the Ten Commandments and the Apostlesâ Creed. He wrote: "To substitute Scripture for the self-revealing Spirit is to put the dead letter in the place of the living Word..."

List of his works

- Autobiographical Letter to Johann Campanus (1531)

- Weltbuch (1534)

- Chronicle of Germany (1538)

- Golden Arch (1538)

- A Universal Chronicle of the World's History from the Earliest Times to the Present

- Book of the Ages

- Chronicle and Description of Turkey

- Paradoxa (1534)

- Preface and Translation into German of Althamer's Diallage

- Seven Sealed Book (1539)

- The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil

- Translation with Additions of Erasmus' Praise of Folly

- The Vanity of Arts and Sciences

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brenning, Robert Wesley. 1979. The ethical hermeneutic of Sebastian Franck, 1499-1542. Philadelphia: s.n.

- Franck, Sebastian, and Edward J. Furcha. 1986. 280 paradoxes or wondrous sayings. Texts and studies in religion, v. 26. Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0889468141

- Hayden-Roy, Patrick Marshall. 1994. The inner word and the outer world: a biography of Sebastian Franck. Renaissance and Baroque studies and texts, v. 7. New York: P. Lang. ISBN 0820420832

- Peters, Ronald H. 1987. The paradox of history: an inquiry into Sebastian Franck's historical consciousness. Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan.

- Williams, George Huntston, and Juan de Valdés. 1957. Spiritual and Anabaptist writers. Documents illustrative of the Radical Reformation. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved January 25, 2023.

- Dipple, Geoffrey. Sebastian Franck in Strasbourg

- Sebastian Franck Christian Classics Ethereal Library, Calvin College.

General philosophy sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Guide to Philosophy on the Internet

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.