Federalist No. 55

| Author | James Madison or Alexander Hamilton |

|---|---|

| Original title | The Total Number of the House of Representatives |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | The Federalist |

| Publisher | New York Packet |

Publication date | February 13, 1788 |

| Media type | Newspaper |

| Preceded by | Federalist No. 54  |

| Followed by | Federalist No. 56  |

Federalist No. 55 is an essay attributed sometimes to either James Madison or Alexander Hamilton, the fifty-fifth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published by The New York Packet on February 13, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published. It is titled "The Total Number of House of Representatives." It is the first of four papers defending the number of members in the House of Representatives against the critics who believed the number of representatives to be inadequate.

The essay addresses critics' objections to the relatively small size of the House of Representatives (sixty-five members). Those concerns are that a relatively small group of legislators might not provide adequate protection against the potential for them to act corruptly. With so few legislators to safeguard the public interest, some were concerned that some might put their own interests with above those of the nation. The essay enumerates the reasons that the ratifiers should not be concerned.

Background

The Articles of Confederation had been largely ineffective. It had a unicameral legislature with clearly delineated but limited powers.[1] The new Constitution replaced the unicameral legislature with a bicameral body. Under the Constitution, the United States House of Representatives would be one of Congress' two chambers. Duties were to be distributed between the House and the United States Senate. The House is responsible for originating bills that authorize the appropriation of funds.[2] Each Representative is elected to a two-year term.[3] There were numerous concerns about the new Congress. The new Constitution was agreed to only after consensus was achieved by including language guaranteeing that each state retained its sovereignty, and that votes in Congress would be en bloc by state.

The concern that the paper addresses is that in its new configuration, the number of representatives in the United States House of Representatives might be insufficient to prevent a small group of legislators from engaging in corruption with not enough safeguards to prevent them.

Number of Representatives

Article 1, Section 2 of the Constitution provides for both the minimum and maximum sizes for the House of Representatives. The number of voting Representatives is now fixed at 435, proportionally representing the population of the fifty states in the United States of America. The Representatives introduce bills and resolutions, and they serve on Committees and offer amendments.[2]

Congress has the power to regulate the size of the House of Representatives, and the size of the House has varied through the years due to the admission of new states and reapportionment following a census. The House of Representatives began with sixty-five members.

| Year | 1789 | 1791 | 1793 | 1803 | 1813 | 1815 | 1817 | 1819 | 1821 | 1833 | 1835 | 1843 | 1845 | 1847 | 1851 | 1853 | 1857 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representatives | 65 | 69 | 105 | 141 | 182 | 183 | 185 | 187 | 213 | 240 | 242 | 223 | 225 | 227 | 233 | 234 | 237 |

| Year | 1861 | 1863 | 1865 | 1867 | 1869 | 1873 | 1883 | 1889 | 1891 | 1893 | 1901 | 1911 | 1913 | 1959 | 1961 | 1963 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representatives | 178 | 183 | 191 | 193 | 243 | 293 | 325 | 330 | 333 | 357 | 386 | 391 | 435 | 436 | 437 | 435 |

In 1911, Congress passed The Apportionment Act of 1911, also known as Public Law 62‚Äď5, which says that the United States House of Representatives can have no more than 435 members. Each state is given at least one representative and the number of representatives per state varies based on population.

The Argument

There is no fixed numeric formula for the ratio between the population and the number of Representatives. The Constitution proposed to begin with sixty-five delegates apportioned by population and tie the number of representatives to the census taken every ten years. The author points out the a new census was to be conducted two years hence (1790). He points out that over time the numbers of House delegates will increase as new states are added and the population grows.

He acknowledges that no republican government can guarantee that it will be completely free of infringement by those who try to pursue their own interests, but the ratifiers should have a degree of trust in the government's power to protect them and to ensure the safety of the republic. The system of "checks and balances" put in place ensures that powers are distribute between the branches, (the executive, judicial, or legislative), and would serve as a check on each other,[4] and every member is voted in by the people every two years.[5]

He addresses the concerns of those who opposed the size of the House of Representatives, initially set at sixty-five, as too small. He points out that there is no single formula used by the states to apportion representatives to their own governing bodies, so their is no set formula for them to use. He then addresses their arguments that such a small number would not provide enough protection should a small group of legislators decide to pursue their own self-interest in lieu of the national interest. The author argues both that legislators cannot assume other positions to access government funds while simultaneously holding their House seat and that after the trials of the American Revolution and aftermath, these men will not be inclined to forsake the national interest so easily for their own personal gain. He concludes with a famous barb:

The truth is that in all cases a certain number [of representatives] at least seems to be necessary to secure the benefits of free consultation and discussion, and to guard against too easy a combination for improper purposes; as, on the other hand, the number ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitude. In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever character composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.[4]

The reference is to an episode in which the demagogue Cleon misled "the massive Athenian Assembly (filled with 6,000 people) into starting the Peloponnesian War. With the new Constitution, the Framers sought to create a new government strong enough to achieve common purposes, but restrained enough that it would not threaten individual rights."[4]

Three-fifths Compromise and Apportionment

The author addresses concerns over the relatively small number of representatives by arguing that with population growth, the number of representatives will also rise. This discussion touches on the argument in Federalist No. 54, explaining that the Three-fifths Compromise will also add to the census and thus to the number of representatives allocated:

Within three years a census is to be taken, when the number may be augmented to one for every thirty thousand inhabitants; and within every successive period of ten years the census is to be renewed, and augmentations may continue to be made under the above limitation. It will not be thought an extravagant conjecture that the first census will, at the rate of one for every thirty thousand, raise the number of representatives to at least one hundred. Estimating the negroes in the proportion of three fifths, it can scarcely be doubted that the population of the United States will by that time, if it does not already, amount to three millions.[6]

Authorship

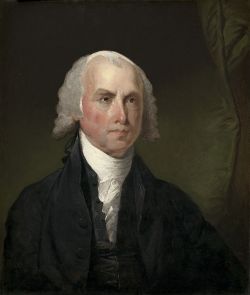

The authorship of this essay is disputed. Textual analysis of the writings of both Alexander Hamilton and James Madison does not definitively assign this text to either one. Madison scholar, Edward Bourne makes no claim for Madison's authorship of this essay.[7] J.C. Hamilton notes similarities between passages in the essay and a speech that Hamilton delivered to the New York Ratifying Convention in June 1788, but since both men would likely have read all the essays, it is not conclusive proof of Hamilton's authorship.[8]

Legacy

While concerns over the behavior of unscrupulous actors has not subsided, the author seems to have been proven right that there were enough checks and balances in place to prevent massive corruption while over time, the concern over the size of the legislature has long since been been alleviated. Since The Apportionment Act of 1911 was passed, there are 435 representatives. As Publius concludes his essay, "Were the pictures which have been drawn by the political jealousy of some among us faithful likenesses of the human character, the inference would be, that there is not sufficient virtue among men for self-government; and that nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring one another."[4] Republican government depends on the virtue. "Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form [of government]."[4]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ "Maryland finally ratifies Articles of Confederation," A&E Television Networks. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 "The House Explained," The United States House of Representatives. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ "The United States House of Representatives," United States House of Representatives. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Federalist No. 55(1788)," The National Constitution Center. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ "The Federalist Papers," Library of Congress. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, "Federalist Nos. 51-60," Library of Congress. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Edward G. Bourne, ‚ÄúThe Authorship of the Federalist,‚ÄĚ The American Historical Review, II [April, 1897]: 443‚Äď60.

- ‚ÜĎ Alexander Hamilton or James Madison, "Federalist No. 55," Founders Online, February 12, 1788. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Amadeo, Kimberly. "How the US House of Representatives Affects the US Economy," The Balance, October 30, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- Bourne, Edward G. ‚ÄúThe Authorship of the Federalist,‚ÄĚ The American Historical Review, II [April, 1897]: 443‚Äď60.

- Hamilton, Alexander, or James Madison. "Federalist No. 55," Founders Online, February 12, 1788. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- Madison, James, and Alexander Hamilton. "Federalist Nos. 51-60," Library of Congress. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

External links

All links retrieved March 25, 2024.

- Text of The Federalist No. 55 Congress.gov.

- "The Federalist Papers," Library of Congress.

- "The House Explained," The United States House of Representatives.

- "Maryland finally ratifies Articles of Confederation," A&E Television Networks.

- "Federalist No. 55(1788)," The National Constitution Center.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.