Adelaide of Italy

| Saint Adelaide | |

|---|---|

| Holy Roman Empress | |

| Born | 931-932 in Burgundy, France |

| Died | December 16 999 in Seltz, Alsace |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Canonized | 1097

by Pope Urban II |

| Feast | December 16 |

| Attributes | empress dispensing alms and food to the poor, often beside a ship |

| Patronage | abuse victims; brides; empresses; exiles; in-law problems; parenthood; parents of large families; princesses; prisoners; second marriages; step-parents; widows |

| Controversy | Not recognized on the Roman Calendar |

Saint Adelaide of Italy, also called Adelaide of Burgundy (931/932 – December 16, 999) was one of the most prominent European woman of the tenth century, whose life was characterized by romantic adventure, court intrigue, and Christian charity.

As a girl, she entered into a political marriage with Lothair II of Italy, who was later allegedly poisoned by the usurper Berengar of Ivrea. Berengar then attempted to force Adelaide to marry his son Athelbert. When Adelaide refused her consent and attempted to flee, Berengar imprisoned her, but she dramatically escaped with the help of a loyal priest by means of a tunnel under the walls of the castle where she was being held. Besieged by Berengar at the castle of her protector in Canossa, Italy, she sent a message to Otto I, the most powerful man in Europe, to rescue her, promising to marry him if he did so. After he came to her aid, they had a successful marriage with five children and eventually rose to the position of Holy Roman Emperor and Empress. She was known as a pious and generous queen, much beloved, but also extravagant in her charity to the point of endangering the kingdom's treasury.

Upon Otto's death, their son, Otto II, came to power. After his marriage, a 16 year old Byzantine princess, however, Adelaide became alienated from her son. Upon Otto II's death and the later death his wife at age 30, Adelaide ruled as regent for her grandson, Otto III, until he rule on his own. She then retired to Selz Abbey in Alsace and devoted herself to prayer and good works, believing that Christ would return around the year 1000. She died on December 16, 999, only days short of the millennium she thought would bring the Second Coming of Christ. Although she is not recognized in the Roman Calendar, her feast day of December 16 is celebrated in many churches in Germany.

Early life and marriages

Adelaide was the daughter of Rudolf II of Burgundy and Bertha of Swabia. Her first marriage, at the age of 15, was to the son of her father's rival in Italy, Lothair II, the nominal King of Italy. Their union, which was contracted when Adelaide was still of child of two years, was part of a political settlement designed to conclude a peace between her father and Hugh of Provence, who was Lothair's faither. The marriage took place fourteen years later and produced one daughter, Emma. In the meantime, after the death of Rudolf, Adelaide's mother had married Hugh.

By this time Berengar, the Marquis of Ivrea, came upon the scene and claimed to be rightful ruler of the Kingdom of Italy. He succeeded in forcing Hugh to abdicate in favor of Lothair; but Lothair soon died, poisoned, as many suspect by Benegar, who then crowned himself king. Attempting to consolidate his claim to power, Berengar commanded the widowed Adelaide to marry his son, Adalbert. The nun Hroswitha of Gandersheim wrote: "Engorged with hatred and envy, Berengar directed his fury against Queen Adelaide. Not only did he seize her throne but at the same time forced the doors of her treasury and carried off, with greedy hand, everything he found… He even took her royal crown…."[1]

Adelaide was disgusted with the prospect of the marriage. Fearing that Berengar and Adalbert had conspired to do way with her husband, she escaped with two handmaids, but was quickly recaptured. According to one version of the story, Willa, the wife of Berengar, turned vicious and tore at Adelaide's hair and jewelry, scratching her face and kicking her. Adelaide was then locked up in one of Berengar's castles on an island in Lake Garda, where she suffered in isolation for four months.

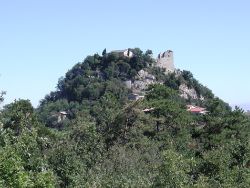

A loyal priest named Warinus (also called Martin), rescued Adelaide by digging a tunnel under or through the castle's thick walls. Each night, he bored a little deeper until Adelaide and her one remaining maid could squeeze out, and all three escaped in a waiting boat. Aggressively pursued, they hid in a wheat field (or forest) while their pursuers poked and prodded the vegetation nearby. In one version of the story, the priest cared for Adelaide by providing fish caught from a nearby lake until Count Adalbert Atto of Canossa arrived to rescue them. In another, the threesome made their way to Adalbert on their own.

Queen and empress with Otto I

Finally safe in Italy, Adelaide put herself under the count's protection protection, but Berengar besieged the castle. At this point, the faithful priest Warinus slipped through siege line and came with a letter from Adelaide to Otto the Great of Germany. Otto, whose English wife Edgitha had died in 946, was at this time the most powerful man in Europe. In the letter, Adelaide promised to marry him, thus uniting her lands with his in a near revival of the empire of Charlemagne, if he would effect her rescue from Berengar.

Otto arrived in Italy in 951, with Berengar fleeing before him. Otto and Adelaide met at the old Lombard capital of Pavia and were married in the same year. They were reported to have liked each other immediately and had a happy marriage despite 20 years of age difference. Even after her many adventures, she was still only 20 years old. The marriage was a fruitful one. Among their five children, four lived to maturity: Henry, born in 952; Bruno, born 953; Matilda, Abbess of Quedlinburg, born about 954; and Otto II, later Holy Roman Emperor, born 955. Adelaide and Otto mainly ruled from Saxony (Northern Germany).

In Germany, Otto crushed of a revolt in 953 by Liudolf, Otto's son by his first marriage. This cemented the position of Adelaide, who retained all her dower lands and some others added to her estate by Otto.

On February 2, 962, Otto was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope John XII, and Adelaide was remarkably crowned Empress at the same ceremony. She assisted her husband with her knowledge of Latin, which he never learned, and accompanied him in 966 on his third expedition to Italy, where she remained with him for six years. She spent generously in charity and church building, which endeared her to ecclesiastics but was a serious drain on the imperial finances.

When Otto I died, in 973, he was succeeded by their son Otto II, and Adelaide for some years exercised a powerful influence at court, until Otto II, then just 17, married the 16-year-old Byzantine princess Theophanu. Already skilled in the arts of court intrigue Theophanu quickly drove a wedge between mother and son, and Adelaide found herself increasingly alienated from the new royal couple.

Eventually, Adelade was driven from court in 978. She lived partly in Italy, and partly with her brother Conrad, king of Burgundy, by whose mediation she was ultimately reconciled to her son. In 983, Otto appointed her his viceroy in Italy, but Otto died the same year. Adelaide and Theophanu then joined ranks to protect the three-year-old king, Otto III as co-regents for the child-king. Within two years, however, Theophanu forced Adelaide to abdicate and exiled her. She lived in Lombardy from 985, until Theophanu herself died in 991. Adelaide was then restored to the regency of her grandson, assisted by Willigis, bishop of Mainz. In 995 Otto III came of age and established his independence from his grandmother. Adelaide then devoted herself exclusively to works of charity, notably the foundation or restoration of religious houses.

Later life

Adelaide had long entertained close relations with Cluny Abbey, then the center of the movement for ecclesiastical reform, and in particular with its abbots Majolus and Odilo. She retired to a monastery she herself had founded c. 991 at Selz in Alsace. There, she took her final title: "Adelheida, by God's gift empress, by herself a poor sinner and God's maidservant." She dedicated herself to prayer and other religious exercises and carried on an intimate correspondence with the abbots of Cluny. She also endowed the foundation of several churches and religious houses. Adelaide also interested herself in the conversion of the Slavs.

Like many other in her time, Adelaide believed that in the year 1,000 the end of the world, or apocalypse, would occur. From the Book of Revelation, she came to believe that Satan, who had been imprisoned by Christ shortly after his first advent, would be released from his imprisonment and then Christ would come again to defeat him. She thus told the abbot of Cluny, "As the thousandth year of our Lord's becoming flesh approaches, I yearn to behold this day, which knows no evening, in the forecourt of our Lord."[1]

Her feast day, December 16, is still kept in many German dioceses.

On her way to Burgundy to support her nephew Rudolf III against a rebellion, Adelaide died at her favorite foundation, Selz Abbey on December 16, 999, just 16 days short of the millennium she thought would bring the Second Coming of Christ. She was buried in the convent of Sts. Peter and Paul, at Selz in Alsace.

Legacy

Perhaps the most significant European woman of her day, Adelaide's life was the subject of many romantic tales and legends, in which she is the historical epitome of a damsel in distress. Although the victim of treachery and intrigue herself, she took no revenge upon her enemies. A deeply pious Christian, her court was said to have the character of religious establishment. Both as reigning Empress and later in retirement, she multiplied monasteries and churches in the various provinces, and was much devoted to the conversion the "pagans" of northern and eastern Europe.

Her life (Epitaphium Adalheidae imperatricis) was written by Saint Odilo of Cluny. It concentrates only for the latter years of the empress, after she had retired from public life and devoted herself to church affairs. Other she was proclaimed a saint and confessor by numerous German bishops and abotts, she is not mentioned in the Roman Calendar. Her feast day of December 16, however, is still celebrated in several German dioceses of the Catholic Church.

| Preceded by: Edith of Wessex |

German Queen 951–961 |

Succeeded by: Theophanu |

| Preceded by: Vacant Title last held by Bertila of Spoleto |

Empress of the Holy Roman Empire 962–973 |

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Women in World History, Adventures of Empress Adelaide Retrieved July 24, 2018.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Attwater, Donald and Catherine Rachel John. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints, 3rd ed. New York: Penguin Books, 1993. ISBN 0140513124

- Coulson, John (ed.). The Saints: A Concise Biographical Dictionary. Hawthorn Books, 1960. OCLC 222552141

- Erdoes, Richard. A.D. 1000: Europe on the Brink of the Apocalypse. Harper & Row, 1988. ISBN 978-0062502957

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved June 15, 2023.

- Adelaide of Italy womeninworldhistory.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.