Yggdrasill

- For other uses, see Yggdrasill (disambiguation).

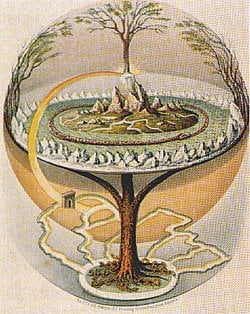

In Norse mythology, Yggdrasil (Old Norse Yggdrasill, IPA: ˈygˌdrasilː; the extra -l is a nominative case marker) is the "World Tree", a gigantic ash tree, thought to connect all the nine worlds of Norse cosmology. Sometimes it is called Mímameiðr or Lérað. According mythology, Ásgard, Álfheim and Vanaheim rest on the branches of Yggdrasil. The trunk is the world-axis piercing through the center of Miðgarðr (often called Midgard), around which Jötunheim is situated, and below which lies Niðavellir, also called Svartálfheim. The three roots stretch down to Hel, Niflheim, and Muspelheim, although only the first world hosts a spring for Yggdrasil.

Yggdrasill in a Norse Context

As a central element of the Norse cosmology, Yggdrasill belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E..[1]

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates a universe divided into nine interrelated realms, some of which attracted considerably greater mythological attention. Of primary importance was the threefold separation of the universe into the realms of the gods (Asgard and Vanaheim, homes of the Aesir and Vanir, respectively), the realm of mortals (Midgard) and the frigid underworld (Niflheim), home of the frost giants. These three realms were supported by an enormous tree (Yggdrasil), with the realm of the gods ensconced among the upper branches, the realm of mortals approximately halfway up the tree (and surrounded by an impassable sea), and the underworld nestled among its roots.

Etymology and alternative names

The most commonly accepted etymology of the world-tree's name is ygg ("terrible") + drasil ("steed"). This seemingly oblique epithet becomes clearer when one recalls that Yggr ("Terrible One") is a name occasionally used to describe Odin, and that "steed" is a common skaldic kenning (poetic allusion) for the gallows. As such, the name of the tree itself alludes to the mythic episode (described elsewhere) of Odin's self-sacrifice upon an enormous ash tree (undertaken for initiation into runic magic).[2] Though the name could also be interpreted more broadly as "terrible horse," this possibility lacks the mythic resonances of the previous option.

Fjölsvinnsmál, a poem in the Poetic Edda, refers to the World Tree as Mimameid (Old Norse: Mímameiðr, "Mímir's tree" ) - a reference to the god of knowledge whose well was nestled into the tree's roots. Most probably, the tree can also be identified with Lærad (Old Norse: Læraðr), a tree rooted at Valhalla, whose shoots and leaves provide food for the goat Heiðrún and the stag Eikþyrnir that live on the roof of the divine hall.[3]

Mythic Depictions

In the Norse cosmology, Yggdrasill provided the axis mundi - the axis of the universe - that united the various realms of gods, giants, and humans. This understanding is bespoken throughout the Prose and Poetic Eddas (the most complete, extant sources in the Norse corpus). The identity between the cosmos and the tree are attested to in the Völuspa, where the deceased sibyl uses it as a metonym to describe the universality of her knowledge:

- Nine worlds I knew, | the nine in the tree

- With mighty roots | beneath the mold.[4]

In a more specific manner, the Grimnismal, a section from the Poetic Edda, provides a clear overview of the Norse perspective on the tree's cosmological significance:

- 31. Three roots there are | that three ways run

- 'Neath the ash-tree Yggdrasil;

- 'Neath the first lives Hel, | 'neath the second the frost-giants,

- 'Neath the last are the lands of men.

- 32. Ratatosk is the squirrel | who there shall run

- On the ash-tree Yggdrasil;

- From above the words | of the eagle he bears,

- And tells them to Nithhogg beneath.

- 35. Yggdrasil's ash | great evil suffers,

- Far more than men do know;

- The hart bites its top, | its trunk is rotting,

- And Nithhogg gnaws beneath.[5]

This account clearly demonstrates the role of the mystical ash in undergirding the universe, with roots in the lower realms and leaves in the realm of the gods. Intriguingly, this account also implicitly affirms the pessimism (or even fatalism) of the classical Nordic worldview, as it describes the world-tree being constantly victimized by stags, who devour its leaves, and a dragon (Niddhogg: "Evil Blow")[6] who is steadily gnawing at its roots. Despite these evil (or at least entropic) influences, Yggdrasill was destined to survive until the cataclysmic battle of Ragnarök (discussed below).

This vision of the heavenly tree is extended by Snorri Sturluson (a thirteenth-century mythography and historian), who assembled the following detailed picture in his synthetic text, Gylfaginning:

- The Ash is the greatest of all trees and best: its limbs spread out over all the world and stand above heaven. Three roots of the tree uphold it and stand exceedingly broad: one is among the Aesir; another among the Rime-Giants, in that place where aforetime was the Yawning Void; the third stands over Niflheim.[7]

The only major difference between the two accounts is the placement of a root in Asgard (the realm of the Aesir) instead of in the human world. Snorri's version then continues, noting that beneath each root lies a well: under the root in Niflheim is Hvergelmir (the "seething cauldron"), understood to be the source of all cold rivers; under the root in the realm of the giants (Jotunheim), one finds "Mimir's Well, wherein wisdom and understanding are stored;"[8] under the third root is the Well of Urd (fate), which is the home of the Norns. Conflating the roles of the Aesir and the Norns, Snorri suggests that the gods ride to this location every day to "hold their tribunal" and "give judgment" (which, one must assume, is directed at their mortal constituents).[9] In this account, the Norns are also assigned a vital function in maintaining the tree, as they are described as being responsible for watering it and packing its roots in rich topsoil.[10]

Given its awe-inspiring role and stature, it is understandable that Yggdrasill would have been conflated with ideas of eternity and permanence:

- Mimameith [Mimir's Tree] its name, | and no man knows

- What root beneath it runs;

- And few can guess | what shall fell the tree,

- For fire nor iron shall fell it.[11]

However, this permanence was to be sorely tested, as the world-tree was destined to be shaken to its roots during the history-negating, eschatological battle of Ragnarök.

Ragnarök

When the legions of giants (led by Loki) converge upon the halls of the gods, Heimdall will hasten to the base of the tree and unearth the Gjallarhorn, which he will then proceed to blow - signalling the advent of the apocalypse.[12]

In the battle the follows, where all of the Aesir are destined to fall in combat with their nemeses, Yggdrasill (the foundation of the universe) "shakes, | and shiver[s] on high // the ancient limbs."[13] Following these ominous signs, the celestial order itself begins to collapse:

- The sun turns black, | earth sinks in the sea,

- The hot stars down | from heaven are whirled;

- Fierce grows the steam | and the life-feeding flame,

- Till fire leaps high | about heaven itself.[14]

Despite this calamity, the fact that a new world will emerge from the embers implies that the tree itself (as figurative "root" of the cosmos) will not be entirely destroyed in the conflict. Indeed, this supposition is validated by the tale of the two human survivors of the apocalypse (Lif and Lifthrasir), who persevere by sheltering themselves in Yggdrasill's branches:

- Othin spake:

- "Much have I fared, | much have I found,

- Much have I got of the gods:

- What shall live of mankind | when at last there comes

- The mighty winter to men?"

- Vafthruthnir spake:

- "In Hoddmimir's wood | shall hide themselves

- Lif and Lifthrasir then;

- The morning dews | for meat shall they have,

- Such food shall men then find."[15]

Yggdrasill in Norse Religion

Given the centrality of Yggdrasill in Norse cosmology, it is reasonable to draw parallels between this mythical entity and the prevalence of trees (both actual and symbolic) in Nordic worship.

Sacrifice

The Nordic/Germanic custom of hanging sacrificial victims from trees could very easily have been developed in the context of this myth, where the victim could be seen playing the role of Odin (as mentioned above). This practice is described in detail in Adam of Bremen's depiction of the Temple of Uppsala:

- The sacrifice is as follows; of every kind of male creature, nine victims are offered. By the blood of these creatures it is the custom to appease the gods. Their bodies, moreover, are hanged in a grove which is adjacent to the temple. This grove is so sacred to the people that the separate trees in it are believed to be holy because of the death or putrefaction of the sacrificial victims.[16]

Germanic veneration of trees

Yggdrasil apparently had smaller counterparts as the Sacred tree at Uppsala, the enormous evergreen of unknown species that stood at the Temple at Uppsala and Irminsul, which was an oak venerated by the pagan Saxons and which was said to connect heaven and earth. The Old Norse form of Irmin was Jörmun and interestingly, just like Ygg, it was one of Odin's names. It appears, then, that Irminsul may have been representing a world tree corresponding to Yggdrasil among the pagan Saxons.

Germanic cultural fondness for tree symbolism appears to have been widespread, with other patron trees such as Thor's Oak appearing in surviving accounts (8th century) and Ahmad ibn Fadlan's account of his encounter with the Scandinavian Rus tribe in the early 10th century, describing them as tattooed from "fingernails to neck" with dark blue "tree patterns."

Potential origins

It has been proposed as an explanation for the World Tree myth that the Cirrus clouds – to a ground standing observer appearing to be virtually stationary on the sky – was imagined to be the branches of a gigantic tree, turned seemingly pale the same way that far away mountains do. Accordingly, rain was held to be the dew dropping from the World Tree. Two old German synonyms for clouds, Wetterbaum and Regenbaum (meaning Weather Tree and Rain Tree), are said to attest to this hypothesis.

Notes

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ Munch, 289.

- ↑ Described in Grímnismál, paraphrased in Lindow, 207.

- ↑ Voluspa (2), in the Poetic Edda, accessed online at sacred-texts.com. 3.

- ↑ "Grímnismál" (31,32,35) in the Poetic Edda, accessed online at sacred-texts.com. 96-99.

- ↑ Lindow, 239.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XV, Brodeur 27.

- ↑ ibid. This is the well of knowledge that Odin sacrificed an eye to drink from.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XV, Brodeur 27-28.

- ↑ See the article on Norns for a more detailed description of this role.

- ↑ "Svipdagsmol" 30, in the Poetic Edda, accessed online at sacred-texts.com. 242.

- ↑ See "Voluspa" 27, in the Poetic Edda: "I know of the horn | of Heimdall, hidden // Under the high-reaching | holy tree." (12).

- ↑ "Voluspa" (47), in the Poetic Edda, accessed online at sacred-texts.com. 20.

- ↑ "Voluspa" (57), in the Poetic Edda, accessed online at sacred-texts.com. 24.

- ↑ "Vafthruthnismol" (44-45), in the Poetic Edda, accessed online at sacred-texts.com. 80-81. Similar to the Biblical tale of Noah, these two survivors will then be left to repopulate the human world (as mentioned in Turville-Petre, 283).

- ↑ Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum, accessed online at northvegr.com.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0-520-02044-8.

- Grammaticus, Saxo. The Danish History (Volumes I-IX). Translated by Oliver Elton (Norroena Society, New York, 1905). Accessed online at The Online Medieval & Classical Library.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- The Poetic Edda. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com.

- Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916. Available online at http://www.northvegr.org/lore/prose/index.php.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964. ISBN 0837174201.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.