Difference between revisions of "Veliky Novgorod" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

==Economy== | ==Economy== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Education is an incredibly important part of the Novgorod culture, as it was one of the first cities in Russian history to build a schoolhouse large enough to hold three hundred students at once. The high levels of education in Novgorod directly spawned many of the key industries for the city, particularly the book making and printing industries. Novgorod also expressed its intellectual history through art, becoming a major center for icon painting and applied decorative arts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Currently, much of the Novgorod economy is funded through foreign investment sources. Novgorod is widely considered to be one of the most econoically open Russian cities, a fact corroborated by tax breaks offted to foreign investors by the local government. Foreign investors tend to focus on heavy industry, particularly the radioelectronical, furniture, chemical fields. The high levels of investment have had some effect on the local population, raising the living standard above many other urban centers in Russia. In paricular, Novgorod has a smaller homeless population than Moscow or St. Petersburg. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

Revision as of 19:02, 17 December 2007

| Historic Monuments of Novgorod and Surroundings* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 604 |

| Region** | European Russia |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1992 (16th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Novgorod, the third largest city in Russia, has deep historical roots to Russian culture as a whole.[1] Novgorod is famed as a center for Russian folk culture, because it does not experience the same influx of Western ideas and peoples found in Moscow or St. Petersburg. The preeminence of Veliky Novgorod in Russian culture is represented by the root of the name, where "Novgorod" is said to be the Russian word for "new city", and "Veliky" means "the Great".

Geography

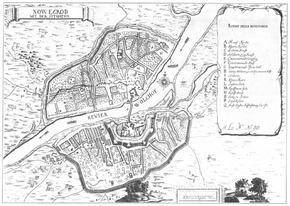

Ancient Novgorod rose to a political force partially due to its ideal location with easy access to both the Oka and the Volga rivers. It is located in the North-West region of Russia, an area commonly referred to as Russia's heartland. The title of the area reflects the high agricultural productivity of the region, as well as the overall economic importance of the area to Russia as a whole.

In modern times, when rivers are no longer the main means of conveyance, Novgorod can be reached by the Russian Route M10. It is situated between the major metropolises Moscow and St. Petersburg, and is rising to become a population center in its own right. Recent estimates put the population at 216, 856, which while lower than the measurements in Soviet Times, still represents a large city by Russian standards.

Economy

Education is an incredibly important part of the Novgorod culture, as it was one of the first cities in Russian history to build a schoolhouse large enough to hold three hundred students at once. The high levels of education in Novgorod directly spawned many of the key industries for the city, particularly the book making and printing industries. Novgorod also expressed its intellectual history through art, becoming a major center for icon painting and applied decorative arts.

Currently, much of the Novgorod economy is funded through foreign investment sources. Novgorod is widely considered to be one of the most econoically open Russian cities, a fact corroborated by tax breaks offted to foreign investors by the local government. Foreign investors tend to focus on heavy industry, particularly the radioelectronical, furniture, chemical fields. The high levels of investment have had some effect on the local population, raising the living standard above many other urban centers in Russia. In paricular, Novgorod has a smaller homeless population than Moscow or St. Petersburg.

History

Early developments Notwithstanding its name, Novgorod is among the most ancient cities among the Eastern Slavs. The Sofia First Chronicle first mentions it in 859; the Novgorodian First Chronicle mentions it first under the year 862 when it was allegedly already a major station on the trade route from the Baltics to Byzantium. Archaelogical excavations in the middle to late twentieth century, however, have found cultural layers dating back only to the late tenth century, the time of the Christianization of Rus' and a century after it was allegedly founded, suggesting that the chronicle entries mentioning Novgorod in the 850s or 860s are later interpolations.[2]

The Varangian name of the city Holmgard (also Holmgarðr, Hólmgarður, Holmgaard, Holmegård) is mentioned in Norse Sagas as existing at a yet earlier stage, but historical facts cannot here be disentangled from legend.[3] Originally, Holmgard referred only to the stronghold southeast of the present-day city, Riurikovo Gorodishche (named in comparatively modern time after Rurik, who supposedly made it his "capital"). Archeological data suggests that the Gorodische, the residence of the Knyaz (konung or prince), dates from the middle of 9th century, whereas the town itself dates only from the end of the 10th century, hence the name Novgorod, "new city".

Princely state within Kievan Rus'

In 882, Rurik's successor, Oleg of Novgorod, captured Kiev and founded the state of Kievan Rus. Novgorod's size as well as its political, economic, and cultural influence made it the second city in Kievan Rus. According to a custom, the elder son and heir of the ruling Kievan monarch was sent to rule Novgorod even as a minor. When the ruling monarch had no such son, Novgorod was governed by posadniks, such as legendary Gostomysl, Dobrynya, Konstantin, and Ostromir. In Norse sagas the city is mentioned as the capital of Gardariki (i.e., the East Slavic lands). Four Viking kings — Olaf I of Norway, Olaf II of Norway, Magnus I of Norway, and Harald Haardraade — sought refuge in Novgorod from enemies at home.

Of all their princes, Novgorodians cherished most the memory of Yaroslav the Wise, who had sat as prince while his father, Vladimir the Great, was prince in Kiev. Yaroslav promulgated the first written code of laws (later incorporated into Russkaya Pravda) among the Eastern Slavs and is said to have granted the city a number of freedoms or privileges, which they often referred to in later centuries as precedents in their relations with other princes. His son, Vladimir, sponsored construction of the great St Sophia Cathedral, more accurately translated as The Cathedral of Holy Wisdom, which stands to this day.

Medieval Republic

In 1136, the Novgorodians dismissed their prince Vsevolod Mstislavich. This date is seen as the traditional beginning of the Novgorod Republic. The city was able to invite and dismiss a number of princes over the next two centuries, but the princely office was never abolished and powerful princes, such as Alexander Nevsky, could assert their will in the city irrespective of the Novgorodians' wishes.[4] The city state controlled most of Europe's North-East, from today's Estonia to the Ural Mountains, making it one of the largest states in medieval Europe, although much of the territory north and east of Lakes Lagoda and Onega were sparsely populated and never organized politically.

One of the most important local figures in Novgorod was the Posadnik or mayor, an official elected by the public assembly (called the Veche) from among the city's boyarstvo or aristocracy. The tysyatsky, or "thousandman," originally the head of the town militia but later a commercial and judicial official, was also elected by the veche. The Archbishop of Novgorod were also important local officials and shared power with the boyars.[5] They were elected by the veche or by the drawing of lots; after their election, they were sent to the metropolitan for consecration.[6]

While a basic outline of the various officials and the veche can be drawn up, the city-state's exact political constitution remains uncertain. The boyars and the archbishop ruled the city collectively, although where one officials power ended and another's began is uncertain. The prince, although reduced in power beginning in about the mid-twelfth century, was represented by his namestnik or lieutenant, and still played important roles as a military commander, legislator, and jurist. The exact composition of the veche, too, is uncertain, with some scholars such as Vasily Kliuchevksii claiming it was democratic in nature, while later scholars, such as Valentin Ianin and Alesandr Khoroshev, see it as a "sham democracy" controlled by the ruling elite.

In the 13th century, Novgorod, while not a member of the Hanseatic League, was the easternmost kontor, or entrepot, of the league, being the source of enormous quanties of luxury (sable, ermine, fox, marmot) and non-luxury furs (squirrel-pelts).[7]

Throughout the Middle Ages, the city thrived culturally. A large number of birch bark letters have been unearthed in excavations, perhaps suggesting wide-spread literacy, although this is uncertain (some scholars suggest that a clerical or scribal elite wrote them on behalf of a largely illiterate populace). It was in Novgorod that the oldest Slavic book written north of Bulgaria and the oldest inscription in a Finnic language were unearthed. Some of the most ancient Russian chronicles were written in the archbishops' scriptorium and the archbishops also promoted iconography and patronized church construction. The Novgorod merchant Sadko became a popular hero of Russian folklore.

Novgorod was never conquered by the Mongols during the Mongol invasion of Rus. The Mongol army turned back about 100 km from the city, not due to the city's strength, but probably because the Mongol commanders did not want to get bogged down in the marshlands surrouding the city. That being said, the grand princes of Moscow, who acted as the tax-collectors for the khans of the Golden Horde, did collect tribute (dan) in Novgorod, most notably Yury Danillovich and his brother, Ivan Kalita.

Within the united Russian state The city's downfall was a result of its inability to feed its large population, making it dependent on the Vladimir-Suzdal region for grain. The main cities in this area, Moscow and Tver, used this dependence to gain control over Novgorod. Eventually Ivan III annexed the city to Muscovy in 1478. Novgorod remained the third largest Russian city, however, until the famine of 1560s and Ivan the Terrible sacking the city and slaughtering thousands of its inhabitants in 1570. The city's merchant elite and nobility were deported to Moscow, Yaroslavl, and elsewhere.

During the Time of Troubles, Novgorodians eagerly submitted to Swedish troops led by Jacob De la Gardie in summer of 1611. The city was restituted to Russia only six years later, by the Treaty of Stolbovo and regained a measure of its former prosperity by the end of the century, when such ambitious buildings as the Cathedral of the Sign and the Vyazhischi Monastery were constructed. The most famous of Russian patriarchs, Nikon, occupied the metropolian see of Novgorod between 1648 and 1652.

In 1727, Novgorod was made an administrative centre of the Novgorod Governorate of the Russian Empire, which was detached from Saint Petersburg Governorate (see Administrative divisions of Russia in 1727-1728). This administrative division existed until 1927. Between 1927 and 1944 the city was a part of Leningrad Oblast, and then became an administrative center of the newly formed Novgorod Oblast.

During World War II, on August 15, 1941, the city was occupied by the German Army. Its historic monuments were systematically annihilated. When the Red Army liberated the city on January 19, 1944, out of 2,536 stone buildings, fewer than forty were still standing. After the war, the downtown was gradually restored. Its chief monuments have been declared the World Heritage Site. In 1998, the city was officially renamed Veliky Novgorod, thus partly reverting to its medieval title "Lord Novgorod the Great".

Sights

No other Russian or Ukrainian city can compete with Novgorod in the variety and age of its medieval monuments. The foremost among these is the St Sophia Cathedral, built between 1045 and 1050 under the patronage of Vladimir Yaroslavich, the son of Yaroslav the Wise (Vladimir is buried in the cathedral along with his mother, Anna.)[8] It is the best preserved of 11th century churches, probably the oldest structure still in use in Russia and the first one to represent original features of Russian architecture (austere stone walls, five helmet-like cupolas). Its frescoes were painted in the 12th century originally on the orders of Bishop Nikita (died 1108) (the "porches" or side chapels were painted in 1144 under Archbishop Nifont) and renovated several times over the centuries, most recently in the nineteenth century.[9] The cathedral features famous bronze gates, which now hang in the west entrance, allegedly made in Magdeburg in 1156 (other sources see them originating in Plock in Poland) and reportedly snatched by Novgorodians from the Swedish town of Sigtuna in 1187. More recent scholarship has determined that the gates probably were purchased in the mid-fifteenth century, apparently at the behest of Archbishop Evfimii II (1429-1458), a lover of Western art and architectural styles.[10]

The Novgorod Kremlin, traditionally known as the Detinets, also contains the oldest palace in Russia (the so-called Chamber of the Facets, 1433), which served as the main meeting hall of the archbishops; the oldest Russian bell tower (mid-15th cent.), and the oldest Russian clock tower (1673). The Palace of Facets, the bell tower, and the clock tower were originally built on the orders of Archbishop Evfimii II, although the clock tower collapsed in the seventeenth century and had to be rebuilt and much of the palace of Evfimii II is no longer extant. Among later structures, the most remarkable are a royal palace (1771) and a bronze monument to the Millennium of Russia, representing the most important figures from the country's history (unveiled in 1862).

Outside the kremlin walls, there are three large churches constructed during the reign of Mstislav the Great. St Nicholas Cathedral (1113-23), containing frescoes of Mstislav's family, graces Yaroslav's Court (formerly the chief square of Novgorod). The Yuriev Monastery (one of the oldest in Russia, 1030) contains a tall, three-domed cathedral from 1119 (built by Mstislav's son, Vsevolod. and Kyurik, the head of the monastery. A similar three-domed cathedral (1117), probably designed by the same masters, stands in the Antoniev Monastery, built on the orders of Antonii, the founder of that monstery.

There are now some fifty still-extant medieval and early modern churches scattered throughout the city and its environs. Some of them were blown up by the Nazis and subsequently restored. The most ancient pattern is represented by those dedicated to Sts Peter and Pavel (on the Swallow's Hill, 1185-92), to Annunciation (in Myachino, 1179), to Assumption (on Volotovo Field, 1180s) and to St Paraskeva-Piatnitsa (at Yaroslav's Court, 1207). The greatest masterpiece of early Novgorod architecture is the Saviour church at Nereditsa (1198).

In the 13th century, tiny churches of the three-paddled design were in vogue. These are represented by a small chapel at the Peryn Monastery (1230s) and St Nicholas' on the Lipnya Islet (1292, also notable for its 14th-century frescoes). The next century saw development of two original church designs, one of them culminating in St Theodor's church (1360-61, fine frescoes from 1380s), and another one leading to the Saviour church on Ilyina street (1374, painted in 1378 by Feofan Grek). The Saviour' church in Kovalevo (1345) was originally frescoed by Serbian masters, but the church was destroyed during the war. While the church has since been rebuilt, the frescoes have not been restored.

During the last century of republican government, some new churches were consecrated to Sts Peter and Paul (on Slavna, 1367; in Kozhevniki, 1406), to Christ's Nativity (at the Cemetery, 1387), to St John the Apostle's (1384), to the Twelve Apostles (1455), to St Demetrius (1467), to St Simeon (1462), and other saints. Generally, they are not thought so innovative as the churches from the previous epoch. Several 12th-century shrines (i.e., in Opoki) were demolished brick by brick and then reconstructed exactly as they used to be, several of them in the mid fifteenth century, again under Archbishop Evfimii II, perhaps one of the greatest patrons of architecture in medieval Novgorod.

Novgorod's conquest by Ivan III in 1478 decisively changed the character of local architecture. Large commissions were thenceforth executed by Muscovite masters and patterned after cathedrals of Moscow Kremlin: e.g., the Saviour Cathedral of Khutyn Monastery (1515), the Cathedral of the Mother of God of the Sign (1688), the St. Nicholas Cathedral of Vyaschizhy Monastery (1685). Nevertheless, the styles of some parochial churches were still in keeping with local traditions: e.g., the churches of Myrrh-bearing Women(1510) and of Sts Boris and Gleb (1586).

In Vitoslavlitsy, along the Volkhov River and the Myachino Lake, close to the Yuriev Monastery, a picturesque museum of wooden architecture was established in 1964. Over 20 wooden buildings (churches, houses and mills) dating from the 14th to the 19th century were transported there from all around the Novgorod region.

Sister cities

Strasbourg, France

Strasbourg, France Rochester, New York, USA

Rochester, New York, USA Bielefeld, Germany

Bielefeld, Germany Watford, UK

Watford, UK Zibo, China

Zibo, China Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine Moss, Norway

Moss, Norway

Notes

- ↑ The Archaeology of Novgorod, by Valentin L. Yanin, in Ancient Cities, Special Issue, (Scientific American), pp 120–127, c 1994. Covers, History, Kremlin of Novgorod, Novgorod Museum of History, preservation dynamics of the soils, and the production of Birch bark documents.

- ↑ V. L. (Valentin Lavrent’evich) Ianin and M. Kh. (Mark Khaimovich) Aleshkovskii, “Proskhozhdenie Novgoroda: (k postanovke problemy),” Istoriia SSSR 2 (1971): 32-61.

- ↑ The meaning of this Norse toponym, "island garden", has no satisfactory explanation. According to Rydzevskaya, the Norse name is derived from the Slavic "Holmgrad" which means "town on a hill" and may allude to the "old town" preceding the "new town", or Novgorod.

- ↑ Michael C. Paul, “The Iaroslavichi and the Novgorodian Veche 1230-1270: A Case Study on Princely Relations with the Veche,” Russian History/ Histoire Russe 31, No. 1-2 (Spring-Summer 2004): 39-59.

- ↑ Michael C. Paul, “Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod Before the Muscovite Conquest.” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 8, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 231-270.

- ↑ Michael C. Paul, “Episcopal Election in Novgorod, Russia 1156-1478.” Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture 72, No. 2 (June 2003): 251-275.

- ↑ Janet Martin, Treasure of the Land of Darkness: the Fur Trade and its Significance for Medieval Russia. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

- ↑ Tatiana Tsarevskaia, St. Sophia's Cathedral in Novgorod (Moscow: Severnyi Palomnik, 2005), 3.

- ↑ Ibid, 14, 19-22, 24, 29, 35.

- ↑ Irena Daniec Jadwiga, The Message of Faith and Symbol in European Medieval Bronze Church Doors (Danbury, CT: Rutledge Books, 1999), Chapter III "An Enigma: The Medieval Bronze Church Door of Płock in the Cathedral of Novgorod," 67-97; Mikhail Tsapenko, ed., Early Russian Architecture (Moscow: Progress Publisher, 1969), 34-38

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

External links

- Novgorod the Great site

- Veliky Novgorod for tourists

- The Faceted Palace of the Kremlin in Novgorod the Great site

- Novgorod - monuments of ancient architecture

- (Russian) Veliky Novgorod's architecture and buildings history

- (Russian) The Millennium of Russia memorial site

- (Russian) Veliky Novgorod city administration site

- Novgorod the Great for a businessman

- (Russian) Veliky Novgorod news

- (Russian) VelikiyNovgorod.ru news agency

- (Russian) Novgorod State University

- Photos tagged with

novgorodon Flickr, photos likely of Novgorod the Great

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.