Difference between revisions of "Valhalla" - New World Encyclopedia

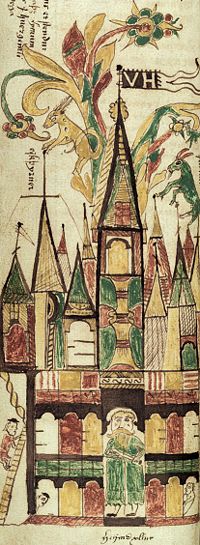

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) (New page: {{started}} right|thumb|200px|In this illustration from a [[17th century Icelandic manuscript, Heimdall is shown guarding the gate of Valhalla.]] ...) |

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

[[Image:AM 738 4to Valhöll.jpg|right|thumb|200px|In this illustration from a [[17th century]] [[Iceland]]ic manuscript, [[Heimdall]] is shown guarding the gate of Valhalla.]] | [[Image:AM 738 4to Valhöll.jpg|right|thumb|200px|In this illustration from a [[17th century]] [[Iceland]]ic manuscript, [[Heimdall]] is shown guarding the gate of Valhalla.]] | ||

| − | '''Valhalla''' ([[Old Norse language|Old Norse]] ''Valhöll'', "Hall of the slain") is [[Odin]]'s hall in [[Norse mythology]], located in [[Gladsheim]] and is the home for those slain gloriously in battle (known as [[Einherjar]]) who are welcomed by [[Bragi]] and escorted to Valhalla by the [[valkyrie]]s. | + | '''Valhalla''' ([[Old Norse language|Old Norse]] ''Valhöll'', "Hall of the slain") is [[Odin]]'s hall in [[Norse mythology]], located in [[Gladsheim]] <define!> and is the home for those slain gloriously in battle (known as [[Einherjar]]) who are welcomed by [[Bragi]] and escorted to Valhalla by the [[valkyrie]]s. <expand!> |

| + | |||

| + | ==Valhalla in a Norse Context== | ||

| + | As an important mythic locale, Valhalla belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the [[Scandinavia|Scandinavian]] and [[Germany|Germanic]] peoples. This mythological tradition developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E..<ref>Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the ''Aesir'', the ''Vanir'', and the ''Jotun''. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war. In fact, the greatest divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.<ref>More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.</ref> The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Further, their [[cosmology|cosmological]] system postulated a universe divided into nine interrelated realms, some of which attracted considerably greater mythological attention. Of primary importance was the threefold separation of the universe into the realms of the gods ([[Asgard]] and [[Vanaheim]], homes of the [[Aesir]] and [[Vanir]], respectively), the realm of mortals (''Midgard'') and the frigid underworld ([[Niflheim]]), the realm of the dead. These three realms were supported by an enormous tree (Yggdrasil), with the realm of the gods ensconced among the upper branches, the realm of mortals approximately halfway up the tree (and surrounded by an impassable sea), and the underworld nestled among its roots. Valhalla, the feasting hall of the Aesir and the gathering place of the honored dead, was an important component of this overall cosmological picture. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Mythic Accounts== | ||

| + | ===Description=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Ragnarök=== | ||

| + | <begin by discussing the role of the Einherjar in the final conflict> | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, after the demise of the existing order (including all of the first-generation [[Aesir]]), the storied walls of Valhalla still stand, presenting the new generation of gods with a dwelling place: | ||

| + | :Then fields unsowed | bear ripened fruit, | ||

| + | :All ills grow better, | and [[Balder|Baldr]] comes back; | ||

| + | :Baldr and [[Minor Aesir#Hödr|Hoth]] dwell | in Hropt's battle-hall.<ref>"Völuspá" (62) in [http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/poe/poe00.htm the ''Poetic Edda''], 26.</ref> | ||

| + | The "Hroptr" mentioned in this passage is simply an epithet for Odin, meaning "god" (or perhaps "tumult").<ref>Orchard, 411.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

== Valgrind == | == Valgrind == | ||

The main gate is called Valgrind, which is described in ''[[Grímnismál]]'' as a "sacred gate", behind which are the "holy doors" and "there are few who can tell the manner by which it is locked". The hall itself has 540 doors, so wide that 800 warriors could walk through side-by-side. It is said that there is room enough for all those chosen. Here, every day, the slain warriors who will assist Odin in [[Ragnarök]], the gods' final conflict with the giants, arm themselves for battle and ride forth by the thousands to engage in mock combat on the plains of [[Asgard]]. Those who die in the combat will be brought back to life. At night, they return to Valhalla to feast on roasted boar ([[Sæhrímnir]]) and drink intoxicating drink. Those who do not get to Valhalla go to the home of the dead ([[Hel (realm)|Hel]]), a place beneath the underworld ([[Niflheim]]), or one of various other places. Those who are lost at sea, for example, are taken to [[Ægir]]'s hall at the bottom of the sea. | The main gate is called Valgrind, which is described in ''[[Grímnismál]]'' as a "sacred gate", behind which are the "holy doors" and "there are few who can tell the manner by which it is locked". The hall itself has 540 doors, so wide that 800 warriors could walk through side-by-side. It is said that there is room enough for all those chosen. Here, every day, the slain warriors who will assist Odin in [[Ragnarök]], the gods' final conflict with the giants, arm themselves for battle and ride forth by the thousands to engage in mock combat on the plains of [[Asgard]]. Those who die in the combat will be brought back to life. At night, they return to Valhalla to feast on roasted boar ([[Sæhrímnir]]) and drink intoxicating drink. Those who do not get to Valhalla go to the home of the dead ([[Hel (realm)|Hel]]), a place beneath the underworld ([[Niflheim]]), or one of various other places. Those who are lost at sea, for example, are taken to [[Ægir]]'s hall at the bottom of the sea. | ||

| Line 16: | Line 36: | ||

In the early 19th century, [[Ludwig I of Bavaria|King Ludwig I of Bavaria]] ordered the construction of the [[Walhalla Temple]], a place of honor for historically notable Germanic figures inspired by Valhalla, near [[Regensburg]], [[Germany]]. | In the early 19th century, [[Ludwig I of Bavaria|King Ludwig I of Bavaria]] ordered the construction of the [[Walhalla Temple]], a place of honor for historically notable Germanic figures inspired by Valhalla, near [[Regensburg]], [[Germany]]. | ||

| − | == | + | ==See Also== |

| − | + | :[[Odin]] | |

| − | + | :[[Asgard]] | |

| + | :[[Valkyrie]] | ||

| + | :[[Heaven]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * DuBois, Thomas A. ''Nordic Religions in the Viking Age''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4. | ||

| + | * Dumézil, Georges. ''Gods of the Ancient Northmen''. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0-520-02044-8. | ||

| + | * Eliade, Mircea. ''The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion''. New York: Harper and Row, 1961. Translated by Willard R. Trask. ISBN 015679201X. | ||

| + | * Grammaticus, Saxo. ''The Danish History'' (Volumes I-IX). Translated by Oliver Elton (Norroena Society, New York, 1905). Accessed online at [http://omacl.org/DanishHistory/ The Online Medieval & Classical Library]. | ||

| + | * Lindow, John. ''Handbook of Norse mythology''. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7. | ||

| + | *Munch, P. A. ''Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes''. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926. | ||

| + | * Orchard, Andy. ''Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend''. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0-304-36385-5. | ||

| + | * ''The Poetic Edda''. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. Accessed online at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/poe/poe00.htm sacred-texts.com]. | ||

| + | * Sturluson, Snorri. ''The Prose Edda''. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916. ''Available online at http://www.northvegr.org/lore/prose/index.php''. | ||

| + | * Turville-Petre, Gabriel. ''Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia.'' New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964. ISBN 0837174201. | ||

| − | |||

[[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | ||

[[Category: Religion]] | [[Category: Religion]] | ||

{{credit|131931105}} | {{credit|131931105}} | ||

Revision as of 16:52, 21 May 2007

Valhalla (Old Norse Valhöll, "Hall of the slain") is Odin's hall in Norse mythology, located in Gladsheim <define!> and is the home for those slain gloriously in battle (known as Einherjar) who are welcomed by Bragi and escorted to Valhalla by the valkyries. <expand!>

Valhalla in a Norse Context

As an important mythic locale, Valhalla belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E..[1]

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the Aesir, the Vanir, and the Jotun. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war. In fact, the greatest divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.[2] The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir.

Further, their cosmological system postulated a universe divided into nine interrelated realms, some of which attracted considerably greater mythological attention. Of primary importance was the threefold separation of the universe into the realms of the gods (Asgard and Vanaheim, homes of the Aesir and Vanir, respectively), the realm of mortals (Midgard) and the frigid underworld (Niflheim), the realm of the dead. These three realms were supported by an enormous tree (Yggdrasil), with the realm of the gods ensconced among the upper branches, the realm of mortals approximately halfway up the tree (and surrounded by an impassable sea), and the underworld nestled among its roots. Valhalla, the feasting hall of the Aesir and the gathering place of the honored dead, was an important component of this overall cosmological picture.

Mythic Accounts

Description

Ragnarök

<begin by discussing the role of the Einherjar in the final conflict>

However, after the demise of the existing order (including all of the first-generation Aesir), the storied walls of Valhalla still stand, presenting the new generation of gods with a dwelling place:

- Then fields unsowed | bear ripened fruit,

- All ills grow better, | and Baldr comes back;

- Baldr and Hoth dwell | in Hropt's battle-hall.[3]

The "Hroptr" mentioned in this passage is simply an epithet for Odin, meaning "god" (or perhaps "tumult").[4]

Valgrind

The main gate is called Valgrind, which is described in Grímnismál as a "sacred gate", behind which are the "holy doors" and "there are few who can tell the manner by which it is locked". The hall itself has 540 doors, so wide that 800 warriors could walk through side-by-side. It is said that there is room enough for all those chosen. Here, every day, the slain warriors who will assist Odin in Ragnarök, the gods' final conflict with the giants, arm themselves for battle and ride forth by the thousands to engage in mock combat on the plains of Asgard. Those who die in the combat will be brought back to life. At night, they return to Valhalla to feast on roasted boar (Sæhrímnir) and drink intoxicating drink. Those who do not get to Valhalla go to the home of the dead (Hel), a place beneath the underworld (Niflheim), or one of various other places. Those who are lost at sea, for example, are taken to Ægir's hall at the bottom of the sea.

In addition to the valkyries and the Einherjar, a rooster named Gullinkambi lives there.

In Beowulf, it is called the shining citadel.

Modern Etymology

Valhalla is a 19th century English mistranslation of the singular Valhöll into a genitival plural form. A more literally correct English translation is Val-hall, but Valhalla is by far the most common form in general use.

Walhalla Temple

In the early 19th century, King Ludwig I of Bavaria ordered the construction of the Walhalla Temple, a place of honor for historically notable Germanic figures inspired by Valhalla, near Regensburg, Germany.

See Also

Notes

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.

- ↑ "Völuspá" (62) in the Poetic Edda, 26.

- ↑ Orchard, 411.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

References

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0-520-02044-8.

- Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York: Harper and Row, 1961. Translated by Willard R. Trask. ISBN 015679201X.

- Grammaticus, Saxo. The Danish History (Volumes I-IX). Translated by Oliver Elton (Norroena Society, New York, 1905). Accessed online at The Online Medieval & Classical Library.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- The Poetic Edda. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com.

- Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916. Available online at http://www.northvegr.org/lore/prose/index.php.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964. ISBN 0837174201.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.