Tyr

Tyr (Old Norse: Týr) is the god of single combat and heroic glory in Norse mythology, portrayed as a one-handed man. In the late Icelandic Eddas, he is described, alternately, as the son of Odin (Prose Edda) or of Hymir (a giant) (Poetic Edda), while the origins of his name (and his possible relationship to Tuisto (see Tacitus's Germania)) suggest he was once considered the father of the gods and head of the pantheon. Corresponding names in other Germanic languages include Tyz (Gothic), Ty (Old Norwegian), Ti (Old Swedish), Tiw, Tiu, Tio, and Tig (Old English) Týr (Modern Icelandic and Faroese), Ziu and Zio (Old High German), and possibly, even Teiw (in lith. tevas, tevs - father; dievas, deive - god) in Proto-Germanic.

Tyr in a Norse Context

As mentioned above, Tyr is a Norse deity, a designation that signifies his membership in a complex of religious, mythological and cosmological beliefs shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E.[1] The tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to exemplify a unified cultural focus on physical prowess and military might.

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the Aesir, the Vanir, and the Jotun. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war, which the Aesir had finally won. In fact, the most major divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.[2] The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir.

Tyr is generally recognized as a "ruler" god among the Aesir, and it is postulated that his role as the head of the pantheon was displaced only gradually by the worship of Odin.

Characteristics

Associated with vigor and victory in battle, Tyr was a warrior god par excellence whose runes were thought to protect the Viking hordes who inscribed them on their weapons and bodies. This historical identification is evidenced by the Roman tendency to conflate the Germanic cult of Tyr with their own veneration of Mars.[3] Further, Tyr was also understood as the god of oaths and legal proceedings:

- In general, too much emphasis has been placed on the warlike aspects of Tyr, and his significance for Germanic law has not been sufficiently recognized. In should be noted that, from the Germanic point of view, there is no contradiction between the concepts "God of War" and "God of Law." War is in fact not only the bloody mingling of combat, but no less a decision obtained between the two combatants and secured by precise rules of law.... So is explained ... how combat between two armies can be replaced by a legal duel, in which the gods grant victory to the party whose right they recognize.[4]

This attribution is also supported by evidence from the Roman period, which seems to describe Tyr as Mars Thingsus ("the god of the þing, or judicial assembly").[5]

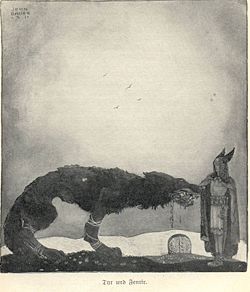

In his instruction manual for Nordic skalds (lyric poets), Snorri Sturluson describes some possible kennings (poetic allusions) that could be used to describe Tyr, including "One-handed God, and Fosterer of the Wolf, God of Battles, Son of Odin."[6] His hand was lost in the feeding of Fenrir (an important myth that is discussed below).

Historical Origins

The name Tyr literally means "god," with an etymology that can be traced by to the Proto-Germanic Tîwaz, earlier Teiwaz, after emerging from the conjectured Proto-Indo-European root *deywos ("god"). Due to this linguistic factor, Tyr is thought to have, at one time, been a major deity (and perhaps even the head of the pantheon), despite his limited representation in the extant mythological corpus.[7]

The oldest attestation of the god is Gothic Tyz (Vienna cod. 140), though the word "Teiw" found inscribed on the Negau Helm may very well be a direct reference to this particular deity, rather than to gods (in general).[8] If this was the case, the runic inscription on this helmet would be the oldest reference to Tyr, as it predates the Gothic evidence by several centuries.

Tîwaz was overtaken in popularity and in authority by both Odin and Thor at some point before the Migration Age. In terms of his relationship to Thor, it is clear that Tyr's linguistic cognates in other Indo-European pantheons were the original possessors of the thunder (i.e. Zeus), though in some cases control of this attribute was ultimately passed on to another god (eg. Dyaus to Indra). Despite this gradual transfer of authority, it is still the case that Tyr is the one of the few gods whose strength is ever compared to Thor's in Eddaic myth.[9]

Major Mythic Tales

According to the Edda, at one stage the gods decided to shackle the wolf Fenrisulfr (Fenris), but the beast broke every chain they put upon him. Eventually they had the dwarves make them a magical ribbon called Gleipnir from such items as a woman's beard and a mountain's roots. But Fenris sensed the gods' deceit and refused to be bound with it unless one of them put his hand in the wolf's mouth. Tyr, known for his great courage, agreed, and the other gods bound the wolf. Fenris sensed that he had been tricked and bit off the god's hand. Fenris will remain bound until the day of Ragnarök.

As a result of this deed, Tyr is called the "Leavings of the Wolf". As the wolf is a frequent metaphor for the all-devouring grave, and with the well-known Eddaic adage "Cattle die, kinsmen die…" in mind, the meaning of this by-name becomes clear. Tyr is glory, the name undying, which shall endure after one's death. And indeed, at the root of his name and the basic Indo-Germanic idea of godhood we find the meaning of "heavenly radiance". Various Germanic words that spring from this same root are the Anglo-Saxon tir (glory), the Old High German Ziori (splendour), and the Old Norse tiv (god, hero).

According to the Prose version of Ragnarok, Tyr is destined to kill and be killed by Garm, the guard dog of Hel. However, in the two poetic versions of Ragnarok, he goes unmentioned; unless one believes that he is the "Mighty One".

In the Lokasenna, Tyr is taunted with cuckoldry by Loki, maybe another hint that he had a consort or wife at one time.

Toponyms of Tyr

Though Tyr/Tiw had become relatively unimportant compared to Odin/Woden in the Nordic and Germanic pantheons, traces of his once-high status can be seen through linguistic traces. For example, the third day of week throughout the English, Germanic and Nordic world is Tuesday (literally "Tiw's day"), which is named after Tyr (as a god of war) in following the Roman example (whose third day (Martis dies) was dedicated to the Roman god of war and the father-god of Rome, Mars). Likewise, this importance can be seen in the names of some plants, including Old Norse Týsfiola (after the Latin Viola Martis); Týviðr, "Tý's wood"; the Swedish Tibast (the Daphne mezereum); and Týrhialm (Aconitum (one of the most poisonous plants in Europe whose helmet-like shape might suggest a warlike connection)). In Norway, the parish and municipality of Tysnes are named after the god. Additionally, the Swedish forest Tiveden may also be named after Tyr, though this may also be due to the definition of tyr as a generic word for "god" (i.e. the forest of the gods).

Tyr rune

The t-rune ᛏ is named after Tyr, and was identified with this god., the reconstructed Proto-Germanic name is Tîwaz (lith. Tevas - father, Dievas or Deivas - god). The rune is sometimes also referred to as Teiwaz, or spelling variants.

The rune was also compared with Mars as in the Icelandic rune poem:

|

|

Modern popular culture

Although representations of Tyr are less common than those of Thor, Odin or Loki, Tyr is often referenced or appears as a warrior figure in many modern depictions, particularly those relating to high fantasy, usually most identifiable by his missing arm and lust for battle.

Tyr has also become a character in the daily comic strip Ink Pen, by Phil Dunlap. Tyr is upset that his brother Thor has a comic book and he doesn't, so he tries to get a job as the mascot for a company. However, Tyr can't find work, mainly due to his "male pattern baldness, atrocious personal hygiene, and uncontrollable anger."

Notes

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.

- ↑ Turville-Petrie, 181.

- ↑ Jan de Vries, quoted in Dumézil, 44. From this, Dumézil explores his Indo-European thesis and enumerates various parallels between Tyr and the Vedic god Mitra.

- ↑ Turville-Petrie, 181.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Skáldskaparmál (IX), p. 113 in Brodeur's translation.

- ↑ Turville-Pietrie, 182; Dumézil, 42-48. See also Orchard, 366 for a brief discussion of this etymology.

- ↑ This inscription is described in excellent detail in Konstantin Reichardt's "The Inscription on Helmet B of Negau" in the journal Language (Vol. 29, No. 3. (Jul. - Sep., 1953), pp. 306-316).

- ↑ However, the older god's fortitude is found to be lacking in comparison to his younger (and more popular contemporary), as in the tale of Hymir's kettle (described in Lindow, 298-299).

Bibliography

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0-520-02044-8.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- Reichardt, Konstantin. "The Inscription on Helmet B of Negau." Language. Vol. 29, No. 3. (Jul. - Sep., 1953). 306-316. ISSN 0097-8507.

- Sturlson, Snorri. The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse Mythology. Introduced by Sigurdur Nordal; Selected and translated by Jean I. Young. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1954. ISBN 0-520-01231-3.

- Snorri Sturluson. The Prose Edda. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964.

External links

- Grimm's Teutonic Mythology (English translation, chapter 9)

- Tyr in Germanic Religion

- Týr and Zisa by William Bainbridge

- Týr Official Site A Viking Metal Band from The Faroe Islands

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.