Sethianism

The Sethians were one of many ancient Gnostic groups that flourished in the Mediterranean world around the time of naiscent Christianity, and may even be older than the first Christian churches.[1] Predominantly Judaic in foundation, and strongly influenced by Platonism, Sethianism provided a synthesis of Judaic and Greek thought with its own distinct interpretation of cosmic creation. The group derived its name from its veneration of the biblical Seth, third son of Adam and Eve, who is depicted in their creation myths as a divine Incarnation.

The influence of Sethianism spread throughout the Mediterranean into the later systems of the Thomasines, the Basilideans and the Valentinians. In particular, Sethianism had an influence on some gnostic Christian gospels such as The Gospel of Judas, which offered non-orthodox views of Jesus' teachings.

Historical Background

Gnosticism is a general term describing various mystically-oriented groups and their teachings, which were most prominent in the first few centuries of the Common Era. It is also applied to later and modern revivals of these teachings. The term gnosticism comes from the Greek word for knowledge, gnosis (γνώσις), referring to esoteric consciousness, which is claimed by gnostics to be the key to unlocking transcendent understanding, self-realization, and/or unity with God.

The origins of gnosticism are not clearly known, but there is general agreement that threads of the teachings must have arisen somewhere in what is today known as the Middle East and Asia Minor—areas in which several cultures could converge and synthesize. Many scholars find the roots of gnosticism in Neoplatonism, which similarly devalues matter and regards the spirit as the true reality. A minority of scholars believe it to be of eastern origin because of its similarities to Buddhist ideas of enlightenment, while others believe it has Mesopotamian or Jewish roots. Gnostic groups became popular around the same time and often in the same places that Christianity did.

Gnosticism was widespread within the early Christian church until the gnostics were expelled in the second and third centuries C.E. Gnosticism was one of the first doctrines to be specifically declared a heresy and gnostic movements were often persecuted as a result. Gnostic groups also suffered under Islamic regimes. The response of orthodoxy to gnosticism significantly defined the evolution of Christian doctrine and church order. After gnostic and orthodox Christianity parted, gnostic Christianity continued as a separate movement in some areas for centuries. However some modern theologians think that several gnostic doctrines were absorbed by Christianity. Gnosticism has reappeared in various forms throughout history and into the contemporary era.

Central to many gnostic beliefs is a dualistic view of the universe, in which matter was seen as essentially illusory while spirit is the only true reality. Christian gnostics emphasized spiritual knowledge and experience, rather than faith and the sacraments of the church, as the key to salvation or unity with God.

Some scholars, notably Gershom Scholem, believe that Jewish gnosticism predated its Christian counterpart. There is indeed some evidence of Jewish mysticism in the pre-Christian era. This can be seen for example in the philosophical writings of Philo of Alexandria, the revelations of Ezekiel (which produced a vast quantity of later kabbalistic speculation), the apocalyptic sections of the Book of Daniel, and detailed explanations about the angelic world in the apocryphal Book of Enoch. The latter certainly contributed to gnostic descriptions and names of the archons, aeons, etc.

However, the data supporting a specifically gnostic Jewish worldview during this period is sparse. In later centuries, the works of the kabbalah clearly indicate a type of Jewish gnosticism. It has yet to be demonstrated, however, that this literature did not evolve out the interaction between gnostics and Jews, rather than springing from Judaism itself.

Christian tradition—especially the writings of Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and Hippolytus—blames the Jewish or Samaritan "sorcerer" Simon Magus as the originator of gnosticism. The Church Fathers described him as founding a gnostic sect that practiced antinomianism—the doctrine that moral laws did not apply to one who had attained salvation or enlightenment. According to the Book of Acts, this Simon was simply a magician whose sin was that he wanted to buy the power of the Holy Spirit for personal gain. It is impossible to say for certain whether his teachings might have constituted a type of gnosticism, Jewish or otherwise.

Mythology

Sethian mythology is centered on the events preceding the story of Genesis, thereby offering a radical reinterpretation of the Torah's description of creation. Rather than emphasizing a fall of human weakness in breaking God's command, Sethians emphasize a crisis of the Divine Fullness as it encounters the ignorance of matter, as depicted in stories about Sophia (Wisdom). Thus, Sethianism posits a transcendent hidden invisible God that is beyond ordinary description, much as Plato (see Parmenides) and Philo had also stated earlier in history. It is only possible to say what God is not, and the experience of it remains something, again, in defiance of rational description. This original God went through a series of emanations, during which its essence is seen as spontaneously expanding into many successive 'generations' of paired male and female beings, called 'aeons'. The first of these is the Barbelo, a figure common throughout Sethianism, who is coactor in the emanations that follow. The aeons that result can be seen as representative of the various attributes of God, themselves indiscernible when not abstracted from their origin. In this sense, the Barbelo and the emanations may be seen as poetic devices allowing an otherwise utterly unknowable God to be discussed in a meaningful way amongst initiates. Collectively, God and the aeons comprise the sum total of the spiritual universe, known as the Pleroma.

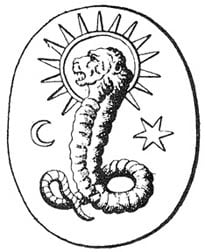

At this point, the myth is still only dealing with a spiritual, non-material universe. In some versions of the myth, the Spiritual Aeon Sophia imitates God's actions in performing an emanation of her own, without the prior approval of the other aeons in the Pleroma. This results in a crisis within the Pleroma, leading to the appearance of the Yaldabaoth, a 'serpent with a lion's head'. This figure is commonly known as the demiurge. This being is at first hidden by Sophia but subsequently escapes, stealing a portion of divine power from her in the process. In this way, the Sethians believe that there is a true god and a false one. The latter is known as the Demiurge (Classical Greek for craftsman-creator) . According to gnostic tradition, the Demiurge created the world following God's command. However, the malevolent Demiurge, which sometimes goes by the name of Yaldabaoth, then usurped the true god's position.

Using this stolen power, Yaldabaoth creates a material world in imitation of the divine Pleroma. To complete this task, he spawns a group of entities known collectively as Archons, 'petty rulers' and craftsmen of the physical world. Like him, they are commonly depicted as theriomorphic, having the heads of animals. Some texts explicitly identify the Archons with the fallen angels described in the Enoch tradition in Judaic apocrypha. At this point the events of the Sethian narrative begin to cohere with the events of Genesis, with the demiurge and his archontic cohorts fulfilling the role of the creator. As in Genesis, the demiurge declares himself to be the only god, and that none exist superior to him; however, the audience's knowledge of what has gone before casts this statement, and the nature of the creator itself, in a radically different light.

The demiurge creates Adam, during the process unwittingly transferring the portion of power stolen from Sophia into the first physical human body. He then creates Eve from Adam's rib, in an attempt to isolate and regain the power he has lost. By way of this he attempts to rape Eve who now contains Sophia's divine power; several texts depict him as failing when Sophia's spirit transplants itself into the Tree of Knowledge; thereafter, the pair are 'tempted' by the serpent, and eat of the forbidden fruit, thereby once more regaining the power that the demiurge had stolen.

Adam and Eve's removal from the Archon's paradise is seen as a step towards freedom from the Archons, and the serpent in the Garden of Eden in some cases becomes a heroic, salvific figure rather than an adversary of humanity or a 'proto-Satan'. Eating the fruit of Knowledge is the first act of human salvation from cruel, oppressive powers.

Texts

Several Gnostic texts contain the Sethian viewpoint, particularly the Apocryphon of John, which describes an unknown God who is defined through negative theology exclusively: he is immovable, invisible, intangible, ineffable. Other Sethian texts include the following works:

Pre-Christian texts:

- The Apocalypse of Adam

Christian texts:

- The Apocryphon of John

- The Thought of Norea

- The Trimorphic Protennoia

- The Coptic Gospel of the Egyptians

- The Gospel of Judas

Later texts:

- Zostrianos

- Three Steles of Seth

- Marsenes

Neo-Sethianism

The classical Sethian doctrine of the 1st and 2nd centuries C.E. has exerted a pervasive influence upon certain mystics and esotericists, from the British-German group the 'Knights of Seth', who were allegedly established in the 1850s, to the Neo-Sethian Hermeticism expounded by the English artist and theurgist Nigel Jackson in his 2003 work 'Celestial Magic'. These manifestations can be termed Neo-Sethian. The Knights of Seth were a 19th century British-German Neo-Sethian group that attempted to resurrect medieval Gnostic and dualistic Christian ideas. While achieving a certain popularity among wealthy young Englishmen in the 1850s, the Knights never gained considerable influence and were by many considered a mere gentlemen's club rather than a religious movement. Apart from a handful of members in Edinburgh and Berlin, the group presently appears to be almost extinct. The group is sometimes referred to by its Latin name Ordo quester Sethiani.

According to the Ordo Equester, Adam's third son Seth was a messiah who could get in touch with the true god and acted as his herald, thwarting the plans of the evil demiurge. The Knights believe that seven prophets will deliver various teachings to humanity. These will then enable men to experience the true, hidden god. This allegedly requires studying different religions and meditation, resulting in a process of recognition (gnosis, Greek language for knowledge).

Notes

- ↑ Sethian Gnosticism: A Literary History Retrieved October 19, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hancock, Curtis L. Studies in Neoplatonism: Ancient and Modern, Volume 6, Wallis & Bregman (Editors), SUNY Press, (1991), Chapter: Negative Theology in Gnosticism and Neoplatonism. ISBN 0-7914-1337-3

- Hoeller, Stephan A. Gnosticism - New Light on the Ancient Tradition of Inner Knowing. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books, 2002. ISBN 0835608166

- Jonas, Hans. Gnosis und spätantiker Geist vol. 2, 1-2. ISBN 3525538413

- Jonas, Hans.The Gnostic Religion. Beacon, 2001. ISBN 0807058017

- King, Karen L. What is Gnosticism? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003. ISBN 067401071X

- Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim. Gnosis on the Silk Road: Gnostic Texts from Central Asia. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993. ISBN 0060645865

- Layton, Bentley. Prolegomena to the Study of Ancient Gnosticism (in The Social World of the First Christians: Essays in Honor of Wayne A. Meeks). Edited by L. Michael White and O. Larry Yarbrough. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1995. ISBN 0800625854

- Longfellow, Ki. The Secret Magdalene. Brattleboro, VT: Eio Books, 2005. ISBN 0975925539

- Pagels, Elaine. The Gnostic Gospels. New York: Vintage Books, 1979. ISBN 0679724532

- Pagels, Elaine. The Johannine Gospel in Gnostic Exegesis. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 1989. ISBN 1555403344

- Stoyanov, Yuri (2004). The Other God. Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08253-3.

- Williams, Michael. Rethinking Gnosticism: An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 0691011273

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.