Difference between revisions of "Samhain" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

The Samhain celebrations have survived in several guises as a festival dedicated to the harvest and the dead. In Ireland and Scotland, the [[Féile na Marbh]], the '[[festival of the dead]]' took place on Samhain. | The Samhain celebrations have survived in several guises as a festival dedicated to the harvest and the dead. In Ireland and Scotland, the [[Féile na Marbh]], the '[[festival of the dead]]' took place on Samhain. | ||

| − | "Samhain (1 November) was the beginning of the Celtic year, at which time any barriers between man and the supernatural were lowered." | + | <blockquote>"Samhain (1 November) was the beginning of the Celtic year, at which time any barriers between man and the supernatural were lowered."<ref name="Chadwick"/></blockquote> |

Revision as of 21:55, 3 February 2009

| Samhain | |

|---|---|

| Observed by | Gaels (Irish people, Scottish people), Neopagans (Wiccans, Celtic Reconstructionists) |

| Type | Festival of the Dead |

| Begins | Northern Hemisphere=Evening of October 31 Southern Hemisphere=Evening of April 30 |

| Ends | Northern Hemisphere: November 1 or November 11 Southern Hemisphere: May 1 |

| Celebrations | Traditional first day of winter in Ireland |

| Related to | Hallowe'en, All Saints Day, All Souls Day |

Samhain (pronounced /ˈsɑːwɪn/, /ˈsaʊ.ɪn/, or /ˈsaʊn/ in English; from Irish samhain, Scottish samhuinn, Old Irish samain "summer's end," from sam "summer" and fuin "end") is a festival on the end of the harvest season in Gaelic and Brythonic cultures, with aspects of a festival of the dead. Many scholars believe that it was the beginning of the Celtic year. [1][2][3]

The term derives from the name of a month in the ancient Celtic calendar, in particular the first three nights of this month, with the festival marking the end of the summer season and the end of the harvest. The Gaelic festival became associated with the Catholic All Souls' Day, and appears to have influenced the secular customs now connected with Halloween. Samhain is also the name of a festival in various currents of Neopaganism inspired by Gaelic tradition.[2][3][4]

Samhain and an t-Samhain are also the Irish and Scottish Gaelic names of November, respectively.

Etymology

The Irish word Samhain is derived from the Old Irish samain, samuin, or samfuin, all referring to 1 November (latha na samna: 'samhain day'), and the festival and royal assembly held on that date in medieval Ireland (oenaig na samna: 'samhain assembly'). Its meaning is glossed as 'summer's end', and the frequent spelling with f suggests analysis by popular etymology as sam ('summer') and fuin ('sunset', 'end'). The Old Irish sam ('summer') is from Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) *semo-; cognates are Welsh haf, Breton hañv, English summer and Old Norse language sumar, all meaning 'summer', and the Sanskrit sáma ("season").[5]

Whitley Stokes in KZ 40:245 (1907) suggests an etymology from Proto-Celtic *samani ('assembly'), cognate to Sanskrit sámana, and the Gothic samana. J. Vendryes in Lexique Étymologique de l'Irlandais Ancien (1959) concludes that these words containing *semo- ('summer') are unrelated to samain, remarking that furthermore the Celtic 'end of summer' was in July, not November, as evidenced by Welsh gorffennaf ('July'). We would therefore be dealing with an Insular Celtic word for 'assembly', *samani or *samoni, and a word for 'summer', saminos (derived from *samo-: 'summer') alongside samrad, *samo-roto-. The Irish samain would be etymologically unrelated to 'summer', and derive from 'assembly'. But note that the name of the month is of Proto-Celtic age, cf. Gaulish SAMON[IOS] from the Coligny calendar, and the association with 'summer' by popular etymology may therefore in principle date to even pre-Insular Celtic times.

Confusingly, Gaulish Samonios (October/November lunation) corresponds to GIAMONIOS, the seventh month (the April/May lunation) and the beginning of the summer season. Giamonios, the beginning of the summer season, is clearly related to the word for winter, Proto-Indo-European *g'hei-men- (Latin hiems, Slavic zima, Greek kheimon, Hittite gimmanza), cf. Old Irish gem-adaig ('winter's night'). It appears, therefore, that in Proto-Celtic the first month of the summer season was named 'wintry', and the first month of the winter half-year 'summery', possibly by ellipsis, '[month at the end] of summer/winter', so that samfuin would be a restitution of the original meaning. This interpretation would either invalidate the 'assembly' explanation given above, or push back the time of the re-interpretation by popular etymology to very early times indeed.

Bealtaine, Lúnasa and Samhain are still today the names of the months of May, August and November in the Irish language. Similarly, an Lùnasdal and an t-Samhain are the modern Scottish Gaelic names for August and November.

History

The Gaulish calendar appears to have divided the year into two halves: the 'dark' half, beginning with the month Samonios (the October/November lunation), and the 'light' half, beginning with the month Giamonios (the April/May lunation). The entire year may have been considered as beginning with the 'dark' half, so that the beginning of Samonios may be considered the Celtic New Year's day. The celebration of New Year itself may have taken place during the 'three nights of Samonios' (Gaulish trinux[tion] samo[nii]), the beginning of the lunar cycle which fell nearest to the midpoint between the autumnal equinox and the winter solstice. The lunations marking the middle of each half-year may also have been marked by specific festivals. The Coligny calendar marks the mid-summer moon (see Lughnasadh), but omits the mid-winter one (see Imbolc). The seasons are not oriented at the solar year, viz. solstice and equinox, so the mid-summer festival would fall considerably later than summer solstice, around 1 August (Lughnasadh). It appears that the calendar was designed to align the lunations with the agricultural cycle of vegetation, and that the exact astronomical position of the Sun at that time was considered less important.

In medieval Ireland, Samhain became the principal festival, celebrated with a great assembly at the royal court in Tara, lasting for three days. After being ritually started on the Hill of Tlachtga, a bonfire was set alight on the Hill of Tara, which served as a beacon, signaling to people gathered atop hills all across Ireland to light their ritual bonfires. The custom has survived to some extent, and recent years have seen a resurgence in participation in the festival.[6]

Samhain was identified in Celtic literature as the beginning of the Celtic year and its description as "Celtic New Year" was popularized in 18th century literature.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag From this usage in the Romanticist Celtic Revival, Samhain is still popularly regarded as the "Celtic New Year" in the contemporary Celtic cultures, both in the Six Celtic Nations and the diaspora.

It is important to remember that all of the written documents in places like Ireland and Wales date to a time after the arrival of Christianity in the 5th century. Thus, while evidence such as folklore and ancient sagas may suggest certain associations with Samhain, these all are observed in a Christian context. There is absolutely no evidence as to whether and how this time might have been observed in any pre-Christian culture.

Celtic folklore

The Samhain celebrations have survived in several guises as a festival dedicated to the harvest and the dead. In Ireland and Scotland, the Féile na Marbh, the 'festival of the dead' took place on Samhain.

"Samhain (1 November) was the beginning of the Celtic year, at which time any barriers between man and the supernatural were lowered."[1]

The night of Samhain, in Irish, Oíche Shamhna and Scots Gaelic, Oidhche Shamhna, is one of the principal festivals of the Celtic calendar, and falls on the 31st of October. It represents the final harvest. In modern Ireland and Scotland, the name by which Halloween is known in the Gaelic language is still Oíche/Oidhche Shamhna. It is still the custom in some areas to set a place for the dead at the Samhain feast, and to tell tales of the ancestors on that night.[2][3][7]

Traditionally, Samhain was time to take stock of the herds and grain supplies, and decide which animals would need to be slaughtered in order for the people and livestock to survive the winter. This custom is still observed by many who farm and raise livestock.[2][3][7]

Bonfires played a large part in the festivities celebrated down through the last several centuries, and up through the present day in some rural areas of the Celtic nations and the diaspora. Villagers were said to have cast the bones of the slaughtered cattle upon the flames. In the pre-Christian Gaelic world, cattle were the primary unit of currency and the center of agricultural and pastoral life. Samhain was the traditional time for slaughter, for preparing stores of meat and grain to last through the coming winter. The word 'bonfire', or 'bonefire' is a direct translation of the Gaelic tine cnámh. With the bonfire ablaze, the villagers extinguished all other fires. Each family then solemnly lit its hearth from the common flame, thus bonding the families of the village together. Often two bonfires would be built side by side, and the people would walk between the fires as a ritual of purification. Sometimes the cattle and other livestock would be driven between the fires, as well.[2][3][7]

Divination is a common folkloric practice that has also survived in rural areas. The most common uses were to determine the identity of one's future spouse, the location of one's future home, and how many children a person might have. Seasonal foods such as apples and nuts were often employed in these rituals. Apples were peeled, the peel tossed over the shoulder, and its shape examined to see if it formed the first letter of the future spouse's name. Nuts were roasted on the hearth and their movements interpreted - if the nuts stayed together, so would the couple. Egg whites were dropped in a glass of water, and the shapes foretold the number of future children. Children would also chase crows and divine some of these things from how many birds appeared or the direction the birds flew.[2][3][7][8]

Ireland

The Ulster Cycle is peppered with references to Samhain. Many of the adventures and campaigns undertaken by the characters therein begin at the Samhain Night feast. One such tale is Echtra Nerai ('The Adventure of Nera') concerning one Nera from Connacht who undergoes a test of bravery put forth by King Ailill. The prize is the king's own gold-hilted sword. The terms hold that a man must leave the warmth and safety of the hall and pass through the night to a gallows where two prisoners had been hanged the day before, tie a twig around one man's ankle, and return. Others had been thwarted by the demons and spirits that harassed them as they attempted the task, quickly coming back to Ailill's hall in shame. Nera goes on to complete the task and eventually infiltrates the sídhe where he remains trapped until next Samhain. Taking etymology into consideration, it is interesting to note that the word for summer expressed in the Echtra Nerai is samraid.

The other cycles feature Samhain as well. The Cath Maige Tuireadh (Battle of Mag Tuired) takes place on Samhain. The deities Morrígan and Dagda meet and have sex before the battle against the Fomorians; in this way the Morrígan acts as a sovereignty figure and gives the victory to The Dagda's people, the Tuatha Dé Danann.

The tale The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn includes an important scene at Samhain. The young Fionn Mac Cumhail visits Tara where Aillen the Burner, one of the Tuatha Dé Danann, puts everyone to sleep at Samhain and burns the place. Through his ingenuity Fionn is able to stay awake and slays Aillen, and is given his rightful place as head of the fianna.

Related festivals

Brittany

In parts of western Brittany, Samhain is still heralded by the baking of kornigou, cakes baked in the shape of antlers to commemorate the god of winter shedding his 'cuckold' horns as he returns to his kingdom in the Otherworld. The Romans[attribution needed] identified Samhain with their own feast of the dead, the Lemuria. This, however, was observed in the days leading up to May 13. With Christianization, the festival in November (not the Roman festival in May) became All Hallows' Day on November 1 followed by All Souls' Day, on November 2. Over time, the night of October 31 came to be called All Hallow's Eve, and the remnants festival dedicated to the dead eventually morphed into the secular holiday known as Halloween.

Wales

The Welsh equivalent of this holiday is called Galan Gaeaf. As with Samhain, this marks the beginning of the dark half of the year, or winter, and it officially begins at sunset on the 31st. The night before is Nos Calan Gaeaf, an Ysbrydnos when spirits are abroad. People avoid churchyards, stiles, and crossroads, since spirits are thought to gather there.

Isle of Man

The Manx celebrate Hop-tu-Naa, which is a celebration of the original New Year's Eve. The term is Manx Gaelic in origin, deriving from Shogh ta’n Oie, meaning "this is the night." Traditionally, children dress as scary beings, carry turnips rather than pumpkins and sing an Anglicized version of Jinnie the Witch. They go from house to house asking for sweets or money.

Hop-tu-Naa is a Celtic festival celebrated in the Isle of Man on 31 October. Predating Halloween, it is the celebration of the original New Year's Eve (Oie Houney). The term is Manx Gaelic in origin, deriving from Shogh ta’n Oie, meaning "this is the night". Hogmanay, which is the Scottish New Year, comes from the same root.

For Hop-tu-Naa children dress up as scary beings and go from house to house with the hope of being given sweets or money, as elsewhere. However the children carry turnips rather than pumpkins and sing an Anglicized version of Jinnie the Witch. The changeover from turnips to pumpkins has also happened in Scotland, where the similar practice is called "guising".

In older times children would have also brought the stumps of turnips with them and batter the doors of those who refused to give them any money! (An ancient form of trick or treat, however this practice appears to have died out.)

Neopaganism

Samhain is observed by various Neopagans in various ways. As forms of Neopaganism can differ widely in both their origins and practices, these representations can vary considerably despite the shared name. Some Neopagans have elaborate rituals to honor the dead, and the deities who are associated with the dead in their particular culture or tradition. Some celebrate in a manner as close as possible to how the Ancient Celts and Living Celtic cultures have maintained the traditions, while others observe the holiday with rituals culled from numerous other unrelated sources, Celtic culture being only one of the sources used.[9][10][4]

Celtic Reconstructionism

Celtic Reconstructionist Pagans tend to celebrate Samhain on the date of first frost, or when the last of the harvest is in and the ground is dry enough to have a bonfire. Like other Reconstructionist traditions, Celtic Reconstructionists place emphasis on historical accuracy, and base their celebrations and rituals on traditional lore from the living Celtic cultures, as well as research into the older beliefs of the polytheistic Celts. At bonfire rituals, some observe the old tradition of building two bonfires, which celebrants and livestock then walk or dance between as a ritual of purification.[11][10][2][3][7]

According to Celtic lore, Samhain is a time when the boundaries between the world of the living and the world of the dead become thinner, allowing spirits and other supernatural entities to pass between the worlds to socialize with humans. It is the time of the year when ancestors and other departed souls are especially honored. Though Celtic Reconstructionists make offerings to the spirits at all times of the year, Samhain in particular is a time when more elaborate offerings are made to specific ancestors. Often a meal will be prepared of favorite foods of the family's and community's beloved dead, a place set for them at the table, and traditional songs, poetry and dances performed to entertain them. A door or window may be opened to the west and the beloved dead specifically invited to attend. Many leave a candle or other light burning in a western window to guide the dead home. Divination for the coming year is often done, whether in all solemnity or as games for the children. The more mystically inclined may also see this as a time for deeply communing with the deities, especially those whom the lore mentions as being particularly connected with this festival.[2][3][7][11][10]

Wicca

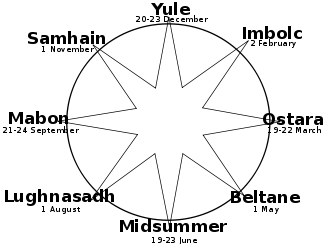

Samhain is one of the eight annual festivals, often referred to as 'Sabbats', observed as part of the Wiccan Wheel of the Year. It is considered by most Wiccans to be the most important of the four 'greater Sabbats'. It is generally observed on October 31st in the Northern Hemisphere, starting at sundown. Samhain is considered by some Wiccans as a time to celebrate the lives of those who have passed on, and it often involves paying respect to ancestors, family members, elders of the faith, friends, pets and other loved ones who have died. In some rituals the spirits of the departed are invited to attend the festivities. It is seen as a festival of darkness, which is balanced at the opposite point of the wheel by the spring festival of Beltane, which Wiccans celebrate as a festival of light and fertility.[12]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Nora Chadwick, The Celts (London: Penguin, 1970, ISBN 0140212116).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Kevin Danaher, The Year in Ireland: Irish Calendar Customs Dublin: Mercier, 1972, ISBN 1856350932).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 F. Marian McNeill, Silver Bough: Calendar of Scottish National Festivals - Hallowe'en to Yule Vol. 3 (Glasgow: Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990, ISBN 0948474041).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ronald Hutton, The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993, ISBN 0631189467).

- ↑ Pokorny, Julius. IEW (1959), s.v. "sem-3," p. 905.

- ↑ Samhain 2007 photos and account of Samhain ritual on the Hill of Tara (and worldwide), Oct. 31, 2007

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Robert O'Driscoll, (ed.), The Celtic Consciousness (New York, NY: Braziller, 1981, ISBN 0807611360).

- ↑ John Gregorson Campbell and Ronald Black, The Gaelic Otherworld (Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd., 2005, ISBN 1841582077).

- ↑ Margot Adler, Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1981, ISBN 0807032379).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Carl McColman, Complete Idiot's Guide to Celtic Wisdom (Alpha Press, 2003, ISBN 0028644174).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Isaac Bonewits, Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism (New York, NY: Kensington Publishing Group, 2006, ISBN 0806527102).

- ↑ Starhawk, The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess, 2nd rev. ed. (New York, Harper and Row, 1989, ISBN 0062508148).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carmichael, Alexander. Carmina Gadelica. Lindisfarne Press, 1992. ISBN 0940262509

- Chadwick, Nora. The Celts. London: Penguin, 1970. ISBN 0140212116

- Danaher, Kevin. The Year in Ireland. Dublin: Mercier, 1972. ISBN 1856350932

- Evans-Wentz, W. Y. The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries. New York, NY: Citadel, 1990. ISBN 0806511605

- MacKillop, James. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0192801201

- McNeill, F. Marian. Silver Bough: Calendar of Scottish National Festivals - Hallowe'en to Yule Vol. 3. Glasgow: Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990. ISBN 0948474041

- Hutton, Ronald. The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Oxford: Blackwell, 1993. ISBN 0631189467

- O'Driscoll, Robert (ed.). The Celtic Consciousness. New York, NY: George Braziller, 1985. ISBN 0807611360

- Campbell, John Gregorson, and Ronald Black. The Gaelic Otherworld. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd., 2005. ISBN 1841582077

- Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1981. ISBN 0807032379

- McColman, Carl. Complete Idiot's Guide to Celtic Wisdom. Alpha Press, 2003. ISBN 0028644174

- Bonewits, Isaac. Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism. New York, NY: Kensington Publishing Group, 2006. ISBN 0806527102

- Starhawk. The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess, 2nd rev. ed. New York, Harper and Row, 1989. ISBN 0062508148

- Kondratiev, Alexei. Samhain: Season of Death and Renewal, An Tríbhís Mhór: The IMBAS Journal of Celtic Reconstructionism 2(1/2) (Samhain 1997/Iombolg 1998). Retrieved February 3, 2009.

External links

- Halloween and Samhain

- Feast of Samhain/Celtic New Year/Celebration of All Celtic Saints

- Samhain at the Hill of Tara, 2007

- The Witches' New Year

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.