Difference between revisions of "Orpheus" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) (New page: {{started}} 300px|right|thumb|The head of Orpheus, from an [[1865 painting by Gustave Moreau.]] '''Orpheus''' (Greek: Ορφεύς; pronuncia...) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Paid}} |

| − | [[Image:Gustave Moreau Orphée 1865.jpg| | + | [[Image:Gustave Moreau Orphée 1865.jpg|250px|right|thumb|The head of Orpheus, from an 1865 painting by [[Gustave Moreau]].]] |

| − | '''Orpheus''' (Greek: Ορφεύς; pronunciation: ''ohr'-fee-uhs'')<ref>The mythological name "Orpheus" is commonly pronounced "ohr'-fee-uhs" in English, although some names have a different pronunciation in ancient Greek; see "Encyclopedia Mythica: Pronunciation guide" webpage:[http://www.pantheon.org/miscellaneous/pronunciations.html Pantheon-pron] | + | '''Orpheus''' ([[Greek language|Greek]]: Ορφεύς; pronunciation: ''ohr'-fee-uhs'')<ref>The mythological name "Orpheus" is commonly pronounced "ohr'-fee-uhs" in English, although some names have a different pronunciation in ancient Greek; see "Encyclopedia Mythica: Pronunciation guide" webpage: [http://www.pantheon.org/miscellaneous/pronunciations.html Pantheon-pron]</ref> is a figure from [[Greek mythology]] called by [[Pindar]] "the minstrel father of songs."<ref>Pindar, ''Pythian Odes IV: For Arkesilas of Kyrene'' (line 177). Translated by Ernest Myers, 1904. Accessible at [http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10717/10717-8.txt Project Gutenberg] Retrieved July 23, 2007.</ref> His name does not occur in [[Homer]] or [[Hesiod]], though he was known by the time of Ibycus (c. 530 B.C.E.).<ref>While Ibycus's reference is the first found in literature (Robbins (1982)), a sculptural depiction of the demigod as a member of the Argonauts, found on "the metopes of the Sikuonian monopteros at Delphi," could predate it. Gantz, 721.</ref> |

| − | Orpheus was | + | In the poetic and mythic corpora, Orpheus was the heroic (i.e. semi-divine) son of the Thracian king Oeagrus and the muse Calliope, a provenance that guaranteed him certain superhuman skills and abilities.<ref>Powell, 303.</ref> In particular, he was described as the most exalted musician in antiquity, whose heavenly voice could charm wild beasts, coax the trees and rocks into dancing, and even divert the course of rivers.<ref>For a list of mythic references to these magical abilities, see Gantz, 721; Godwin, 243.</ref> In addition, Apollodorus (and other classical mythographers) describe Orpheus as the sailing companion of [[Jason and the Argonauts]].<ref>Apollodorus, 1.9.16; Apollonios, ''Argonotica'', 4.891-911.</ref> |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | Some of the other traits associated with Orpheus (and with the [[Orphism|mystery religion bearing his name]]) suggest that he was an [[divination|augur and seer]]; practiced magical arts, especially [[astrology]]; founded or rendered accessible many important cults, such as those of [[Apollo]] and the Thracian god [[Dionysus]]; instituted mystic rites both public and private; and prescribed initiatory and purificatory rituals.<ref>Grote, 21.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Mythology== | ==Mythology== | ||

| − | + | ===Origins and early life=== | |

| − | == | + | The mythic accounts describing the provenance of Orpheus lack a consensus on the parents of the musical hero. While most suggest that his father was Oeagrus (the king of Thrace) and that his mother was the muse [[Calliope]],<ref>This opinion is held by Bakchylides, [[Plato]], Apollonios, Diodorus, and others (Gantz, 725).</ref> many alternate lineages also exist. Most significantly, he is occasionally seen as the son of [[Apollo]] and either Calliope or a mortal woman—an understandable attribution, given their mutual prowesses in the performing arts.<ref>Pindar, Asklepiades, et al (Gantz, 725).</ref> |

| − | Orpheus | ||

===Argonautic expedition=== | ===Argonautic expedition=== | ||

{{details|Argonautica}} | {{details|Argonautica}} | ||

| − | Orpheus | + | Despite his reputation as an effete musician, one of the earliest mythic sagas to include Orpheus was as a crew-member on Jason's expedition for the Golden Fleece. In some versions, the [[centaur]] [[Chiron]] cryptically warns the leader of the Argonauts that their expedition will only succeed if aided by the musical youth.<ref>Herodorus, AR 1.23; Gantz 721; Marlow, 363.</ref> Though it initially seems that such a cultured individual would be of little help on an ocean-going quest, Orpheus's mystically efficacious music comes to the aid of the group on more than one occasion: |

| − | + | :[I]t was by his music that the ship Argo herself was launched; after the heroes had for some time succumbed to the charms of the women of Lemnos, who had killed their husbands, it was Orpheus whose martial notes recalled them to duty; it was by his playing that the Symplegadae or clashing rocks in the Hellespont were fixed in their places; the Sirens themselves lost their power to lure men to destruction as they passed, for Orpheus' music was sweeter; and finally the dragon itself which guarded the golden fleece was lulled to sleep by him.<ref>Marlow, 363. See also: Apollodorus 1.9.25; Godwin, 245.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Death of Eurydice=== | |

| + | [[Image:Cervelli Orfeo ed Euridice.jpg|right|thumb|220px|Orpheus and Eurydice, by Federigo Cervelli]] | ||

| + | Without a doubt, the most famous tale of Orpheus concerns his doomed love for his wife Eurydice. At the wedding of the young couple, the comely bridge is pursued by Aristaeus (son of Apollo), who drunkenly desires to have his way with her. In her panic, Eurydice fails to watch her step and inadvertently runs through a nest of snakes, which proceed to fatally poison her.<ref>Powell, 303; Godwin, 243. Conversely, Ovid's version has the young woman bitten as she gaily frolics through a field: "For as the bride, amid the Naiad train, // Ran joyful, sporting o'er the flow'ry plain, // A venom'd viper bit her as she pass'd; // Instant she fell, and sudden breath'd her last". [http://classics.mit.edu/Ovid/metam.10.tenth.html Metamorphoses]] (Book X). Retrieved July 23, 2007.</ref> Beside himself, the musical hero began to play such bitter-sweet dirges that all the [[nymph]]s and gods wept. On their advice, Orpheus traveled to the [[Hades#Hades, abode of the dead|underworld]], using his music to soften the hard hearts of [[Hades]] and [[Persephone]],<ref>He was the only person ever to succeed in earning a reprieve from them.</ref> who agreed to allow Eurydice to return with him to earth on one condition: he should walk in front of her and not look back until they had reached the upper world. As he returned, each step grew more tentative than the last as he anxiously began to doubt the trustworthiness of the King of the Underworld&mash;perhaps his seemingly kind offer had simply been a cruel trick! In his anxiety, Orpheus broke his promise and turned around, only to see the shade of his wife swallowed up by the darkness of the underworld, never to be seen again.<ref>Powell, 303-306; Ovid, [http://classics.mit.edu/Ovid/metam.10.tenth.html Metamorphoses]] (Book X); Vergil, ''Georgics'' (4.457-527); Apollodorus, ''The Library'', (1.3.2). Retrieved June 11, 2008.</ref> | ||

| − | The | + | The precise origin of this tale is uncertain. Certain elements, such as the attempted sexual assault by Aristaeus, were later inclusions (in that case, by [[Vergil]]), though the basic "facts" of the story have much greater antiquity. For instance, [[Plato]] suggests that the infernal gods only "presented an apparition" of Eurydice to him, and that his weakness was a direct result of his character (as a musician).<ref>See Bowra (1952) ''passim'' for a detailed discussion of the various Greek and Roman sources of this myth, along with an in-depth analysis of the relationship between these accounts. See also: Gantz, 723-725.</ref> |

| − | + | This mythic trope (the descent to the Underworld) is paralleled in tales from various mythic systems worldwide: the Japanese myth of [[Izanagi]] and [[Izanami]], the [[Akkad]]ian/[[Sumerian]] myth of ''[[Inanna]]'s Descent to the Underworld'', and [[Maya mythology|Mayan]] myth of [[Ix Chel]] and [[Itzamna]]. The theme of "not looking back" is reflected in the story of [[Lot]]'s wife, during their escape from [[Sodom]]. More directly, the story of Orpheus is similar to the ancient Greek tales of [[Persephone]] capture at the hands of Hades and of similar stories depicting [[Adonis]] held captive in the underworld. | |

===Death=== | ===Death=== | ||

[[Image:Cropped version of Dürer drawing.JPG|thumb|right|200px|[[Albrecht Dürer]] envisioned the death of Orpheus in this pen and ink drawing, 1494 (Kunsthalle, Hamburg)]] | [[Image:Cropped version of Dürer drawing.JPG|thumb|right|200px|[[Albrecht Dürer]] envisioned the death of Orpheus in this pen and ink drawing, 1494 (Kunsthalle, Hamburg)]] | ||

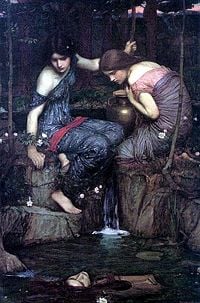

| − | [[Image:Nymphs finding the Head of Orpheus.jpg|right|thumb|200px|''Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus'', by | + | [[Image:Nymphs finding the Head of Orpheus.jpg|right|thumb|200px|''Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus'', by John William Waterhouse]] |

| − | + | The unpleasant death of Orpheus (he is rent asunder by the [[Maenads]] (ravening devotees of [[Dionysus]]) is another popular tale in the mythic accounts of the musician god. What is less certain is the precise motive(s) of these women for their manual dismemberment of the youth, though one of two motivations tend to be stressed in the surviving materials: first, the Maenads were offended when Orpheus decided to voluntarily abstain from heterosexual intercourse after the death of his beloved; second, they felt that he had, in some way, insulted Dionysos.<ref>Powell, 303. A third motive, namely that Orpheus refused to initiate women into all of the cultic mysteries, is rather interesting, but is only sporadically covered in any extant sources (Powell, 303; Gantz, 723).</ref> Each of these will be (briefly) addressed below. | |

| − | According to | + | According to some versions of the story (notably Ovid's), Orpheus forswore the love of women after the death of Eurydice and took only male youths as his lovers; indeed, he was reputed to be the one who introduced pederasty to the Thracians, teaching them to "love the young in the flower of their youth." This unexpected turn in Ovid's account is summarized by Bakowski: |

| − | + | :Within the space of a few short lines Orpheus has gone from tragic lover of Eurydice to trivial pederast worthy of inclusion in Strato's ''Musa Puerilis''. The sudden transfer of sexual energy to the male, the revulsion toward the female, the total obliviousness towards Eurydice, who will not be mentioned again for some seven hundred lines as Orpheus concertizes on pederastic and misogynist themes, is telling and invites a closer look at Ovid's estimation of Greek love.<ref>Bakowski, 29.</ref> | |

| + | Indeed, some scholars suggest that this episode was primarily included to allow Ovid to present a critique of the patriarchal, one-sided relationships between men and boys in Hellenic culture.<ref>Bakowski, 29-31 and ''passim''.</ref> Regardless, the Ovidian account then proceeds to detail how the Thracian Maenads, Dionysus' followers, angry for having been spurned by Orpheus in favor of "tender boys," first threw sticks and stones at him as he played, though his music was so beautiful that even the rocks and branches refused to hit him. Enraged, the Maenads tore him to pieces during the frenzy of their Bacchic orgies.<ref>Godwin, 244. Later, the story was given a moralistic, Christian angle. For example, [[Albrecht Dürer]]'s drawing ''(illustration, right)'' includes a ribbon high in the tree, on which is lettered ''Orfeus der erst puseran'' ("Orpheus, the first sodomite").</ref> | ||

| − | + | Conversely, according to a Late Antique summary of [[Aeschylus]]'s lost play ''Bassarids'', Orpheus at the end of his life disdained the worship of all gods save the sun, which he called [[Apollo]]. One morning, he went to the [[Oracle]] of [[Dionysus]] to salute his god at dawn, but was torn to death by Thracian Maenads for not honoring his previous patron, Dionysus.<ref>Gantz, 723-724.</ref> | |

| − | + | Regardless of the cause of his demise, the Maenads then proceeded to fling the mortal remains of the heavenly musician into a nearby river. His head, still singing mournful songs, floated down the swift Hebrus to the Mediterranean shore. There, the winds and waves carried him to Lesbos, where the inhabitants buried his head and a shrine was built in his honor; there, his oracle prophesied, until it was silenced by Apollo.<ref>''Life of Apollonius of Tyana'', Book V.14.</ref> The Muses gathered up the fragments of his body and buried them at Leibethra (below [[Mount Olympus]]), where the nightingales sang over his grave. His soul returned to the underworld, where he was re-united at last with his beloved Eurydice.<ref>Powell, 303; Godwin, 244; Marlow, 28. As an aside, one can also visit [http://www.ancient-bulgaria.com/2006/08/31/tatul-the-possible-tomb-of-orpheus/ this website], which provides images and text pertaining to a ancient Bulgarian grave thought to perhaps have belonged to the historical Orpheus. Retrieved July 23, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | ==Orphic | + | ==The Orphic Mysteries== |

| − | {{ | + | {{main|Orphism}} |

| − | + | [[Image:Orfeu-atenas.jpg|right|thumb|220px|''Orpheus with the lyre and surrounded by beasts'', Museum Christian-Byzantine, [[Athens]]]] | |

| − | In addition to | + | In addition to this unique role in Greek mythology, the figure of Orpheus was also central to [[mystery religion]] (specifically in what was called the [[Orphism|Orphic tradition]]). Orpheus, like Dionysus and Demeter, was credited with a miraculous return from the world of the dead, a fact that seemed to capture the Hellenic religious imagination. For this reason, he was credited as the founder of the sect and numerous mystical/theological poems (which were used in their liturgies) were attributed to him. Of this vast literature, only two examples survive whole: a set of [[hymns]] composed at some point in the second or third century C.E., and an Orphic Argonautica composed somewhere between the fourth and sixth centuries C.E. Earlier Orphic literature, which may date back as far as the sixth century B.C.E., survives only in papyrus fragments or in quotations.<ref>Price, 118-121.</ref> |

| − | + | In addition to serving as a storehouse of mythological data along the lines of [[Hesiod]]'s ''[[Theogony]]'', Orphic poetry was recited in mystery-rites and purification rituals. [[Plato]] in particular tells of a class of vagrant beggar-priests who would go about offering purifications to the rich, a clatter of books by Orpheus and Musaeus in tow.<ref>Plato, ''The Republic'' 364c-d.</ref> Those who were especially devoted to these cults often practiced [[vegetarianism]], abstention from [[sex]], and refrained from eating eggs and beans—which came to be known as the ''Orphikos bios'', or "Orphic way of life".<ref>Moore, p. 56 says that "the use of eggs and beans was forbidden, for these articles were associated with the worship of the dead".</ref> | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | The | + | The Derveni papyrus, found in Derveni, Macedonia, in 1962, contains a philosophical treatise that is an allegorical commentary on an Orphic poem in hexameters, a theogony concerning the birth of the gods, produced in the circle of the philosopher Anaxagoras, written in the second half of the fifth century B.C.E..E. Fragments of the poem are quoted making it "the most important new piece of evidence about Greek philosophy and religion to come to light since the Renaissance."<ref>[http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/bmcr/2006/2006-10-29.html Richard Janko, Bryn Mawr Classical Review, (2006) of K. Tsantsanoglou, G.M. Parássoglou, T. Kouremenos (editors), 2006. ''The Derveni Papyrus''] (Florence: Olschki) series "Studi e testi per il "Corpus dei papiri filosofici greci e latini," vol. 13]). Retrieved June 10, 2008. Also briefly described in Price, 118-121.</ref> The papyrus dates to around 340 B.C.E., during the reign of Philip II of Macedon, making it Europe's oldest surviving manuscript. |

| − | + | The eighteenth-century historian William Mitford wrote that the very earliest form of a higher and cohesive ancient Greek religion was manifest in the Orphic poems, arguing: | |

| + | :But the very early inhabitants of Greece had a religion far less degenerated from original purity. To this curious and interesting fact, abundant testimonies remain. They occur in those poems, of uncertain origin and uncertain date, but unquestionably of great antiquity, which are called the poems of Orpheus or rather the Orphic poems [particularly in the Hymn to Jupiter, quoted by Aristotle in the seventh chapter of his Treatise on the World: Ζευς πρωτος γενετο, Ζευς υςατος, x. τ. ε]; and they are found scattered among the writings of the philosophers and historians."<ref>Mitford, 89.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Likewise, W. K. C. Guthrie considered that Orpheus was the founder of mystery religions and the first to reveal to men the meanings of the initiation rites: | |

| − | + | :"As founder of mystery-religions, Orpheus was first to reveal to men the meaning of the rites of initiation (teletai). We read of this in both Plato and Aristophanes (Aristophanes, ''Frogs'', 1032; Plato, ''Republic'', 364e, a passage which suggests that literary authority was made to take the responsibility for the rites." Guthrie goes on to write about "... charms and incantations of Orpheus which we may also read of as early as the fifth century B.C.E.. Our authority is Euripides, ''Alcestis'' (referencing the Charm of the Thracian Tablets) and in ''Cyclops'', the spell of Orpheus".<ref>Guthrie, 17.</ref> | |

==Post-classical Orpheus == | ==Post-classical Orpheus == | ||

| − | The Orpheus legend has remained a popular subject for writers, artists, musicians and filmmakers | + | The Orpheus legend has remained a popular subject for writers, artists, musicians and filmmakers, inspiring poetry, novels, musical compositions, visual art, animation, and films.<ref>As [[Wikipedia]] is openly editable, it is often the best place to find up-to-date information on pop culture. As a result, please consult [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orpheus their article] on Orpheus for a summary of these artistic endeavors. Retrieved June 11, 2008.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Orpheus | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 184: | Line 62: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | * | + | * Apollodorus. ''Gods & Heroes of the Greeks''. Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Michael Simpson. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977. ISBN 0-87023-205-3 |

| − | *Albertus | + | *Bernabé, Albertus (ed.). ''Orphicorum et Orphicis similium testimonia et fragmenta. Poetae Epici Graeci. Pars II. Fasc. 1.'' Bibliotheca Teubneriana, München/Leipzig: K.G. Saur, 2004. ISBN 3-598-71707-5 |

| − | * | + | * Bowra, C.M. "Orpheus and Eurydice." ''The Classical Quarterly'' (New Series). Vol. 2, No. 3/4. (Jul. - Oct., 1952). 113-126. |

| − | *William | + | * Gantz, Timothy. ''Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993. ISBN 080184410X |

| − | * | + | * Godwin, William. ''The Pantheon''. New York: Garland Pub., 1984. ISBN 0824035607 |

| − | * | + | * Guthrie, W. K. C. ''Orpheus and Greek Religion: a Study of the Orphic Movement''. London: Methuen, 1952. |

| − | * | + | * Makowski, John F. "Bisexual Orpheus: Pederasty and Parody in Ovid." ''The Classical Journal''. Vol. 92, No. 1. (Oct. - Nov., 1996). 25-38. |

| − | * | + | * Marlow, A.N. "Orpheus in Ancient Literature." ''Music & Letters''. Vol. 35, No. 4. (Oct., 1954). 361-369. |

| − | *''The Mystical Hymns of Orpheus'' | + | * Moore, Clifford H. ''Religious Thought of the Greeks''. Kessinger Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0766151301. |

| − | * | + | * Nilsson, Martin P. ''Greek Popular Religion''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1940. Also accessible online at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/gpr/ sacred-texts.com] Retrieved June 11, 2008. |

| − | + | * Powell, Barry B. ''Classical Myth'', 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. ISBN 0-13-716714-8 | |

| + | * Price, Simon. ''Religions of the Ancient Greeks''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-38867-8 | ||

| + | * Robbins, Emmet. "Famous Orpheus" in John Warden's ''Orpheus: the metamorphoses of a myth''. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982. ISBN 0802055184 | ||

| + | * Rohde, Erwin. "The Orphics" in ''Psyche: The Cult of Souls and Belief in Immortality among the Greeks''. Chicago: Ares, 1987. ISBN 0890054770 | ||

| + | * Rose, H.J. ''A Handbook of Greek Mythology''. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1959. ISBN 0-525-47041-7 | ||

| + | * Ruck, Carl A.P. and Daniel Staples. ''The World of Classical Myth''. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1994. ISBN 0-89089-575-9 | ||

| + | *Smith, William. "Orpheus." ''Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology''. 1870. Accessible online at [http://www.ancientlibrary.com/smith-bio/2392.html ancientlibrary.com] Retrieved June 11, 2008. | ||

| + | *Taylor, Thomas (trans.). ''The Mystical Hymns of Orpheus''. Accessible online at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/hoo sacred-texts.com] Retrieved June 11, 2008. | ||

| + | *West, Martin Litchfield. ''The Orphic Poems''. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. ISBN 0198148542 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 17, 2022. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | * [http://www.theoi.com/Text/OrphicHymns1.html The Orphic Hymns translated by Thomas Taylor] | ||

[[Category:Religion]] | [[Category:Religion]] | ||

| − | [[Category:Philosophy and | + | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] |

{{credit|141712696}} | {{credit|141712696}} | ||

Latest revision as of 02:17, 18 November 2022

Orpheus (Greek: Ορφεύς; pronunciation: ohr'-fee-uhs)[1] is a figure from Greek mythology called by Pindar "the minstrel father of songs."[2] His name does not occur in Homer or Hesiod, though he was known by the time of Ibycus (c. 530 B.C.E.).[3]

In the poetic and mythic corpora, Orpheus was the heroic (i.e. semi-divine) son of the Thracian king Oeagrus and the muse Calliope, a provenance that guaranteed him certain superhuman skills and abilities.[4] In particular, he was described as the most exalted musician in antiquity, whose heavenly voice could charm wild beasts, coax the trees and rocks into dancing, and even divert the course of rivers.[5] In addition, Apollodorus (and other classical mythographers) describe Orpheus as the sailing companion of Jason and the Argonauts.[6]

Some of the other traits associated with Orpheus (and with the mystery religion bearing his name) suggest that he was an augur and seer; practiced magical arts, especially astrology; founded or rendered accessible many important cults, such as those of Apollo and the Thracian god Dionysus; instituted mystic rites both public and private; and prescribed initiatory and purificatory rituals.[7]

Mythology

Origins and early life

The mythic accounts describing the provenance of Orpheus lack a consensus on the parents of the musical hero. While most suggest that his father was Oeagrus (the king of Thrace) and that his mother was the muse Calliope,[8] many alternate lineages also exist. Most significantly, he is occasionally seen as the son of Apollo and either Calliope or a mortal woman—an understandable attribution, given their mutual prowesses in the performing arts.[9]

Argonautic expedition

Despite his reputation as an effete musician, one of the earliest mythic sagas to include Orpheus was as a crew-member on Jason's expedition for the Golden Fleece. In some versions, the centaur Chiron cryptically warns the leader of the Argonauts that their expedition will only succeed if aided by the musical youth.[10] Though it initially seems that such a cultured individual would be of little help on an ocean-going quest, Orpheus's mystically efficacious music comes to the aid of the group on more than one occasion:

- [I]t was by his music that the ship Argo herself was launched; after the heroes had for some time succumbed to the charms of the women of Lemnos, who had killed their husbands, it was Orpheus whose martial notes recalled them to duty; it was by his playing that the Symplegadae or clashing rocks in the Hellespont were fixed in their places; the Sirens themselves lost their power to lure men to destruction as they passed, for Orpheus' music was sweeter; and finally the dragon itself which guarded the golden fleece was lulled to sleep by him.[11]

Death of Eurydice

Without a doubt, the most famous tale of Orpheus concerns his doomed love for his wife Eurydice. At the wedding of the young couple, the comely bridge is pursued by Aristaeus (son of Apollo), who drunkenly desires to have his way with her. In her panic, Eurydice fails to watch her step and inadvertently runs through a nest of snakes, which proceed to fatally poison her.[12] Beside himself, the musical hero began to play such bitter-sweet dirges that all the nymphs and gods wept. On their advice, Orpheus traveled to the underworld, using his music to soften the hard hearts of Hades and Persephone,[13] who agreed to allow Eurydice to return with him to earth on one condition: he should walk in front of her and not look back until they had reached the upper world. As he returned, each step grew more tentative than the last as he anxiously began to doubt the trustworthiness of the King of the Underworld&mash;perhaps his seemingly kind offer had simply been a cruel trick! In his anxiety, Orpheus broke his promise and turned around, only to see the shade of his wife swallowed up by the darkness of the underworld, never to be seen again.[14]

The precise origin of this tale is uncertain. Certain elements, such as the attempted sexual assault by Aristaeus, were later inclusions (in that case, by Vergil), though the basic "facts" of the story have much greater antiquity. For instance, Plato suggests that the infernal gods only "presented an apparition" of Eurydice to him, and that his weakness was a direct result of his character (as a musician).[15]

This mythic trope (the descent to the Underworld) is paralleled in tales from various mythic systems worldwide: the Japanese myth of Izanagi and Izanami, the Akkadian/Sumerian myth of Inanna's Descent to the Underworld, and Mayan myth of Ix Chel and Itzamna. The theme of "not looking back" is reflected in the story of Lot's wife, during their escape from Sodom. More directly, the story of Orpheus is similar to the ancient Greek tales of Persephone capture at the hands of Hades and of similar stories depicting Adonis held captive in the underworld.

Death

The unpleasant death of Orpheus (he is rent asunder by the Maenads (ravening devotees of Dionysus) is another popular tale in the mythic accounts of the musician god. What is less certain is the precise motive(s) of these women for their manual dismemberment of the youth, though one of two motivations tend to be stressed in the surviving materials: first, the Maenads were offended when Orpheus decided to voluntarily abstain from heterosexual intercourse after the death of his beloved; second, they felt that he had, in some way, insulted Dionysos.[16] Each of these will be (briefly) addressed below.

According to some versions of the story (notably Ovid's), Orpheus forswore the love of women after the death of Eurydice and took only male youths as his lovers; indeed, he was reputed to be the one who introduced pederasty to the Thracians, teaching them to "love the young in the flower of their youth." This unexpected turn in Ovid's account is summarized by Bakowski:

- Within the space of a few short lines Orpheus has gone from tragic lover of Eurydice to trivial pederast worthy of inclusion in Strato's Musa Puerilis. The sudden transfer of sexual energy to the male, the revulsion toward the female, the total obliviousness towards Eurydice, who will not be mentioned again for some seven hundred lines as Orpheus concertizes on pederastic and misogynist themes, is telling and invites a closer look at Ovid's estimation of Greek love.[17]

Indeed, some scholars suggest that this episode was primarily included to allow Ovid to present a critique of the patriarchal, one-sided relationships between men and boys in Hellenic culture.[18] Regardless, the Ovidian account then proceeds to detail how the Thracian Maenads, Dionysus' followers, angry for having been spurned by Orpheus in favor of "tender boys," first threw sticks and stones at him as he played, though his music was so beautiful that even the rocks and branches refused to hit him. Enraged, the Maenads tore him to pieces during the frenzy of their Bacchic orgies.[19]

Conversely, according to a Late Antique summary of Aeschylus's lost play Bassarids, Orpheus at the end of his life disdained the worship of all gods save the sun, which he called Apollo. One morning, he went to the Oracle of Dionysus to salute his god at dawn, but was torn to death by Thracian Maenads for not honoring his previous patron, Dionysus.[20]

Regardless of the cause of his demise, the Maenads then proceeded to fling the mortal remains of the heavenly musician into a nearby river. His head, still singing mournful songs, floated down the swift Hebrus to the Mediterranean shore. There, the winds and waves carried him to Lesbos, where the inhabitants buried his head and a shrine was built in his honor; there, his oracle prophesied, until it was silenced by Apollo.[21] The Muses gathered up the fragments of his body and buried them at Leibethra (below Mount Olympus), where the nightingales sang over his grave. His soul returned to the underworld, where he was re-united at last with his beloved Eurydice.[22]

The Orphic Mysteries

In addition to this unique role in Greek mythology, the figure of Orpheus was also central to mystery religion (specifically in what was called the Orphic tradition). Orpheus, like Dionysus and Demeter, was credited with a miraculous return from the world of the dead, a fact that seemed to capture the Hellenic religious imagination. For this reason, he was credited as the founder of the sect and numerous mystical/theological poems (which were used in their liturgies) were attributed to him. Of this vast literature, only two examples survive whole: a set of hymns composed at some point in the second or third century C.E., and an Orphic Argonautica composed somewhere between the fourth and sixth centuries C.E. Earlier Orphic literature, which may date back as far as the sixth century B.C.E., survives only in papyrus fragments or in quotations.[23]

In addition to serving as a storehouse of mythological data along the lines of Hesiod's Theogony, Orphic poetry was recited in mystery-rites and purification rituals. Plato in particular tells of a class of vagrant beggar-priests who would go about offering purifications to the rich, a clatter of books by Orpheus and Musaeus in tow.[24] Those who were especially devoted to these cults often practiced vegetarianism, abstention from sex, and refrained from eating eggs and beans—which came to be known as the Orphikos bios, or "Orphic way of life".[25]

The Derveni papyrus, found in Derveni, Macedonia, in 1962, contains a philosophical treatise that is an allegorical commentary on an Orphic poem in hexameters, a theogony concerning the birth of the gods, produced in the circle of the philosopher Anaxagoras, written in the second half of the fifth century B.C.E. Fragments of the poem are quoted making it "the most important new piece of evidence about Greek philosophy and religion to come to light since the Renaissance."[26] The papyrus dates to around 340 B.C.E., during the reign of Philip II of Macedon, making it Europe's oldest surviving manuscript.

The eighteenth-century historian William Mitford wrote that the very earliest form of a higher and cohesive ancient Greek religion was manifest in the Orphic poems, arguing:

- But the very early inhabitants of Greece had a religion far less degenerated from original purity. To this curious and interesting fact, abundant testimonies remain. They occur in those poems, of uncertain origin and uncertain date, but unquestionably of great antiquity, which are called the poems of Orpheus or rather the Orphic poems [particularly in the Hymn to Jupiter, quoted by Aristotle in the seventh chapter of his Treatise on the World: Ζευς πρωτος γενετο, Ζευς υςατος, x. τ. ε]; and they are found scattered among the writings of the philosophers and historians."[27]

Likewise, W. K. C. Guthrie considered that Orpheus was the founder of mystery religions and the first to reveal to men the meanings of the initiation rites:

- "As founder of mystery-religions, Orpheus was first to reveal to men the meaning of the rites of initiation (teletai). We read of this in both Plato and Aristophanes (Aristophanes, Frogs, 1032; Plato, Republic, 364e, a passage which suggests that literary authority was made to take the responsibility for the rites." Guthrie goes on to write about "... charms and incantations of Orpheus which we may also read of as early as the fifth century B.C.E. Our authority is Euripides, Alcestis (referencing the Charm of the Thracian Tablets) and in Cyclops, the spell of Orpheus".[28]

Post-classical Orpheus

The Orpheus legend has remained a popular subject for writers, artists, musicians and filmmakers, inspiring poetry, novels, musical compositions, visual art, animation, and films.[29]

Notes

- ↑ The mythological name "Orpheus" is commonly pronounced "ohr'-fee-uhs" in English, although some names have a different pronunciation in ancient Greek; see "Encyclopedia Mythica: Pronunciation guide" webpage: Pantheon-pron

- ↑ Pindar, Pythian Odes IV: For Arkesilas of Kyrene (line 177). Translated by Ernest Myers, 1904. Accessible at Project Gutenberg Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ While Ibycus's reference is the first found in literature (Robbins (1982)), a sculptural depiction of the demigod as a member of the Argonauts, found on "the metopes of the Sikuonian monopteros at Delphi," could predate it. Gantz, 721.

- ↑ Powell, 303.

- ↑ For a list of mythic references to these magical abilities, see Gantz, 721; Godwin, 243.

- ↑ Apollodorus, 1.9.16; Apollonios, Argonotica, 4.891-911.

- ↑ Grote, 21.

- ↑ This opinion is held by Bakchylides, Plato, Apollonios, Diodorus, and others (Gantz, 725).

- ↑ Pindar, Asklepiades, et al (Gantz, 725).

- ↑ Herodorus, AR 1.23; Gantz 721; Marlow, 363.

- ↑ Marlow, 363. See also: Apollodorus 1.9.25; Godwin, 245.

- ↑ Powell, 303; Godwin, 243. Conversely, Ovid's version has the young woman bitten as she gaily frolics through a field: "For as the bride, amid the Naiad train, // Ran joyful, sporting o'er the flow'ry plain, // A venom'd viper bit her as she pass'd; // Instant she fell, and sudden breath'd her last". Metamorphoses] (Book X). Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ He was the only person ever to succeed in earning a reprieve from them.

- ↑ Powell, 303-306; Ovid, Metamorphoses] (Book X); Vergil, Georgics (4.457-527); Apollodorus, The Library, (1.3.2). Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ↑ See Bowra (1952) passim for a detailed discussion of the various Greek and Roman sources of this myth, along with an in-depth analysis of the relationship between these accounts. See also: Gantz, 723-725.

- ↑ Powell, 303. A third motive, namely that Orpheus refused to initiate women into all of the cultic mysteries, is rather interesting, but is only sporadically covered in any extant sources (Powell, 303; Gantz, 723).

- ↑ Bakowski, 29.

- ↑ Bakowski, 29-31 and passim.

- ↑ Godwin, 244. Later, the story was given a moralistic, Christian angle. For example, Albrecht Dürer's drawing (illustration, right) includes a ribbon high in the tree, on which is lettered Orfeus der erst puseran ("Orpheus, the first sodomite").

- ↑ Gantz, 723-724.

- ↑ Life of Apollonius of Tyana, Book V.14.

- ↑ Powell, 303; Godwin, 244; Marlow, 28. As an aside, one can also visit this website, which provides images and text pertaining to a ancient Bulgarian grave thought to perhaps have belonged to the historical Orpheus. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Price, 118-121.

- ↑ Plato, The Republic 364c-d.

- ↑ Moore, p. 56 says that "the use of eggs and beans was forbidden, for these articles were associated with the worship of the dead".

- ↑ Richard Janko, Bryn Mawr Classical Review, (2006) of K. Tsantsanoglou, G.M. Parássoglou, T. Kouremenos (editors), 2006. The Derveni Papyrus (Florence: Olschki) series "Studi e testi per il "Corpus dei papiri filosofici greci e latini," vol. 13]). Retrieved June 10, 2008. Also briefly described in Price, 118-121.

- ↑ Mitford, 89.

- ↑ Guthrie, 17.

- ↑ As Wikipedia is openly editable, it is often the best place to find up-to-date information on pop culture. As a result, please consult their article on Orpheus for a summary of these artistic endeavors. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Apollodorus. Gods & Heroes of the Greeks. Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Michael Simpson. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977. ISBN 0-87023-205-3

- Bernabé, Albertus (ed.). Orphicorum et Orphicis similium testimonia et fragmenta. Poetae Epici Graeci. Pars II. Fasc. 1. Bibliotheca Teubneriana, München/Leipzig: K.G. Saur, 2004. ISBN 3-598-71707-5

- Bowra, C.M. "Orpheus and Eurydice." The Classical Quarterly (New Series). Vol. 2, No. 3/4. (Jul. - Oct., 1952). 113-126.

- Gantz, Timothy. Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993. ISBN 080184410X

- Godwin, William. The Pantheon. New York: Garland Pub., 1984. ISBN 0824035607

- Guthrie, W. K. C. Orpheus and Greek Religion: a Study of the Orphic Movement. London: Methuen, 1952.

- Makowski, John F. "Bisexual Orpheus: Pederasty and Parody in Ovid." The Classical Journal. Vol. 92, No. 1. (Oct. - Nov., 1996). 25-38.

- Marlow, A.N. "Orpheus in Ancient Literature." Music & Letters. Vol. 35, No. 4. (Oct., 1954). 361-369.

- Moore, Clifford H. Religious Thought of the Greeks. Kessinger Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0766151301.

- Nilsson, Martin P. Greek Popular Religion. New York: Columbia University Press, 1940. Also accessible online at sacred-texts.com Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- Powell, Barry B. Classical Myth, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. ISBN 0-13-716714-8

- Price, Simon. Religions of the Ancient Greeks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-38867-8

- Robbins, Emmet. "Famous Orpheus" in John Warden's Orpheus: the metamorphoses of a myth. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982. ISBN 0802055184

- Rohde, Erwin. "The Orphics" in Psyche: The Cult of Souls and Belief in Immortality among the Greeks. Chicago: Ares, 1987. ISBN 0890054770

- Rose, H.J. A Handbook of Greek Mythology. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1959. ISBN 0-525-47041-7

- Ruck, Carl A.P. and Daniel Staples. The World of Classical Myth. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1994. ISBN 0-89089-575-9

- Smith, William. "Orpheus." Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 1870. Accessible online at ancientlibrary.com Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- Taylor, Thomas (trans.). The Mystical Hymns of Orpheus. Accessible online at sacred-texts.com Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- West, Martin Litchfield. The Orphic Poems. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. ISBN 0198148542

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.