Difference between revisions of "Montanism" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→History) |

|||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | Although the extent to which Montanist teaching was heretical may be debatable, that they constituted | + | Although the extent to which Montanist teaching was heretical may be debatable, that they quickly constituted challenge to epsicopal authority is clear. Shortly after Montanus' conversion to Christianity, he began travelling among the rural settlements of [[Asia Minor]], preaching and testifying. Dates are uncertain, but it appears that the beginning of Monatanus' career was 155-165 C.E. Accompanied by Prisca (also called Priscilla) and Maximilla, he offered a charismatic ministry featuring ecstatic spiritual manifestations. |

| − | + | Montanus claimed to have received a series of direct revelations from the Spirit. As they went, "the Three," as they were called, spoke in ecstatic trance-like states and urged their followers to fast and pray, so that they might share these personal revelations. His preachings spread from his native Phrygia, where he reportedly proclaimed the village of [[Pepuza]] as the site of the [[New Jerusalem]], across the contemporary Christian world, to Africa and Gaul. In Catharage they attracted the allegiance of Tertullian, who became the leader of a Montanist faction in that city that persisted until they were reconciled with the Church through the ministry of St. Augustine. The Montanists were generally recognized for their holiness and refused to compromise with Roman authorities on questions of honoring Roman state deities. As a result, they counted many martyrs among its numbers. Recent studies suggest that numerous Christian martrys, including the famous Saints [[Perpetua]] and Felicitas, who died in Carthage in the early second century, may have been Montanists or at least influenced by Montanism. | |

| − | + | The movement was partly inspired by a reading of the ''[[Gospel of John]]''— "I will send you the advocate [''[[paraclete]]''], the spirit of truth" (Heine 1987, 1989; Groh 1985). Together with an insistence on ascetic disciple and chastity, this doctrine of [[continuing revelation]] represented a challenge teaching authority of the bishops and split several Christian communities. Inscriptions from the region of Phryigia indicate that whole towns had become Montanist. The orthodox hierarchy thus fought to suppress it. Bishop Apollinarius found the church at [[Ancyra]] torn in two, and he opposed the "false prophesy" (quoted by Eusebius 5.16.5). Bishop St.[[Irenaeus]] of Lyon, who visited Rome during the height of the controversy, in the pontificate of [[Pope Eleuterus|Eleuterus]], returned to find Lyon in dissension, and was inspired to write the first great statement of the mainstream Catholic position, ''Adversus Haereses.'' Euleuterus, for his part, seems to have approved of the Montanists at first but was later | |

| + | dissuaded from this view. | ||

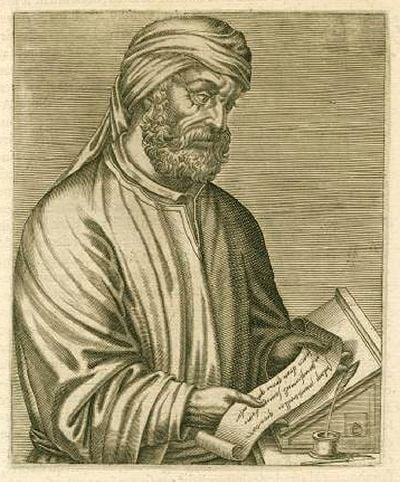

| − | + | [[Image:Tertullian.JPG|thumb|400px|Tertullian]] | |

| − | + | Tertullian claimed that only false accusations had moved him to condemn the movement: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

:"For after the Bishop of Rome had acknowledged the prophetic gifts of Montanus, Prisca, and Maximilla, and, in consequence of the acknowledgment, had bestowed his peace on the churches of Asia and Phrygia, he (Praxeas), by importunately urging false accusations against the prophets themselves and their churches... compelled him to recall the pacific letter which he had issued, as well as to desist from his purpose of acknowledging the said gifts. By this Praxeas did a twofold service for the devil at Rome: he drove away prophecy, and he brought in heresy; he put to flight the Paraclete, and he crucified the Father." (Adversus Praxeam, I) | :"For after the Bishop of Rome had acknowledged the prophetic gifts of Montanus, Prisca, and Maximilla, and, in consequence of the acknowledgment, had bestowed his peace on the churches of Asia and Phrygia, he (Praxeas), by importunately urging false accusations against the prophets themselves and their churches... compelled him to recall the pacific letter which he had issued, as well as to desist from his purpose of acknowledging the said gifts. By this Praxeas did a twofold service for the devil at Rome: he drove away prophecy, and he brought in heresy; he put to flight the Paraclete, and he crucified the Father." (Adversus Praxeam, I) | ||

| − | [[Tertullian]] was by far the best known defender of Montanists. A respected champion of | + | A native of Cathage, [[Tertullian]] was by far the best known defender of Montanists. He seems to have become a Montanist around the turn of third century, about 20 years or so after his conversion to Christianity. A respected intellectual champion of orthodoxy in every other respect, Tertulllian decried the spiritual laxity and corruption that he believed had infected the Catholic Church in his day. He believed that the new prophecy was genuinely motivated and saw it as a remedy to the Church's ills. His later writings grew increasinly caustic in decrying the moral corruption of what he now called "the church of a lot of bishops" (''On Modesty''). On questions of doctrine, however, he claimed that: "In this alone we differ, in that we do not receive the scond marriage (as Catholics allowed) and we do not refuse the prohecy of Montanus concerning the future judgment." |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Local councils in Asia Minor reported moved against the Montanists as early as 177. When once such synod excommunicated Maximilla, she reportedly exclaimed "I am driven away like the wolf from the sheep. I am no wolf: I am [[Logos|word]] and spirit and power." Nevertheless the new prophecy retained significant pockets of influence in the region, as well as in North Africa and even Rome. Inscriptions in the [[Tembris]] valley of northern Phrygia, dated between 249 and 279, openly proclaim allegiance of towns to Montanism. Constantine the Great and other Emperors later passed laws against, and in by the time of Justian I, such legislations was stictly enforced. Still, small communities of Montanists reportedly persisted into the eighth century in some regions. | |

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 86: | Line 48: | ||

==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| + | *Butler, Rex D., ''The New Prophecy & "New Visions": Evidence of Montanism in the Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas'', Catholic University of America Press, 2006. ISBN: 0813214556 | ||

* Groh, Dennis E. 1985. "Utterance and exegesis: Biblical interpretation in the Montanist crisis," in Groh and Jewett, ''The Living Text'' (New York) pp 73 – 95. | * Groh, Dennis E. 1985. "Utterance and exegesis: Biblical interpretation in the Montanist crisis," in Groh and Jewett, ''The Living Text'' (New York) pp 73 – 95. | ||

* Heine, R.E., 1987 "The Role of the Gospel of John in the Montanist controversy," in ''Second Century v. 6, pp 1 – 18. | * Heine, R.E., 1987 "The Role of the Gospel of John in the Montanist controversy," in ''Second Century v. 6, pp 1 – 18. | ||

* Heine, R.E., 1989. "The Gospel of John and the Montanist debate at Rome," in ''Studia Patristica'' 21, pp 95 – 100. | * Heine, R.E., 1989. "The Gospel of John and the Montanist debate at Rome," in ''Studia Patristica'' 21, pp 95 – 100. | ||

*[[Elaine Pagels|Pagels, Elaine]], 2003. ''Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas'' ISBN 0375501568, contains a brief introduction to Montanism, with notes in chapter "God's Word or Human Words?" | *[[Elaine Pagels|Pagels, Elaine]], 2003. ''Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas'' ISBN 0375501568, contains a brief introduction to Montanism, with notes in chapter "God's Word or Human Words?" | ||

| − | * Trevett, Christine, 1996. ''Montanism: Gender, Authority and the New Prophecy'' | + | * Trevett, Christine, 1996. ''Montanism: Gender, Authority and the New Prophecy''. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN: 0521528704 |

[[Category:Ancient Roman Christianity]] | [[Category:Ancient Roman Christianity]] | ||

Revision as of 18:30, 23 May 2006

Montanism was an early Christian sectarian movement beginning in the mid-2nd century CE, named after its founder Montanus. It's defining characteristic was a belief that its founder, together with the two prophetesses Priscilla and Miximilla, were in special and direct communion with the Holy Spirit. It flourished in and around the region of Phrygia, and also spread to other regions in the Roman Empire before Christianity was generally tolerated or legal. Strongly devoted to and spiritual purity, refusing any compromise with the secular authority, the Montanists counted many martyrs among their adherents. No less an intellectual power than the otherwise orthodox Tertullian supported their cause and beliefs.

Although the bishops eventually declared Montanism to be a heresy, the sect persisted well into the fourth century and continued in some places for another three or four hundred years.

The condemnation of Montanism by the orthodox Church put a virtual end to the tradition of Christian prophecy. Thereafter, recognized Christian prophets would be few and far between. Because of its practice of esctatic communion with the Spirit and its claim of continuing revelation through its prophets, some people have drawn parallels between Montanism and Pentecostalism.

Doctrine and Practice

Although Motanist writings were reportedly numerous, no works of the early Montanists survive. Tertullian's later writings contain defenses of their doctrines and practices, but his major work in support of Montanus, "De Ecstasia," is lost, probably destroyed by church authorities as essentially heretical. We are thus dependant for the most part on critics of the movement, usually writing more than a century after the fact, for information. Citations from the church historians Eusebius and Epiphanius are the most important of these.

And essential teaching of the "new prophecy," as it was called, was that the Paraclete, or Holy Spirit, would purity the church in preparation for the imminent coming of Christ. Its leaders channeled revelation from God urging moral rigor, especially chastity, fasting, and willingness to face martyrdom rather than flee or pay bribes. Remarraige was strictly forbidden.

With regard to martyrdom, Montanus is quoted as saying, "Do not desire to depart this life in bed, in miscarriages, in soft ssfevers, but in martydoms, that He who suffered for you may be glorified." (Tertullian, "De anima" 54)

And regarding chastity, Priscilla says: "The chaste minister knows how to minister holiness. For those who purify their hears both see vision... and hear manifest voice."

So far, there is little to suggest serious heresy, although doctrines of moral perfectionism and insistence the true Christians must be willing to become martyrs were later declared outside the bounds of orthodoxy. In addition, the insistence that true ministers of God must be gifted with both visionary and auditory revelation constituted a challenge to the authority of the bishops, for whom the sacrament of ordination was sufficient.

Teh Montanists were also accused of going too far when, for example, Montanus declared: "I am the Father, the Word, and the Paraclete," and Meximilla proclaimed: "Hear not me, but hear Christ). It is questionable, of course, whether Montanus and his companions claimed such titles for themselves or simply believed that they were channels through whom the Spirt spoke, just as did the Old Testament prophets, who punctuated there prophecies by saying: "I am the Lord." (Is. 42:8, Ezek. 20:7, Hos 12:9, etc.) Evidence fo this view is given by Epiphanius, who quotes Montanus as saying: Behold, the man is like a lyre, and I dart like the plectrum. The man sleeps, and I am awake. ("Haer.", 67:4)

A more serious problem was the allegation that for the Montanists, the "new prophecy" superceded the old. Moreover, the idea that woman could act as minisster of Christ had already been rejected by the bishops. Added to this, Priscilla reportedly claimed a night vision in which Christ slelpt by her side "in the form of woman, clad in bright garment." This vision revealed that Pepuza, the Montanist headquarters, would be the place that "Jerusalem above comes down."

History

Although the extent to which Montanist teaching was heretical may be debatable, that they quickly constituted challenge to epsicopal authority is clear. Shortly after Montanus' conversion to Christianity, he began travelling among the rural settlements of Asia Minor, preaching and testifying. Dates are uncertain, but it appears that the beginning of Monatanus' career was 155-165 C.E. Accompanied by Prisca (also called Priscilla) and Maximilla, he offered a charismatic ministry featuring ecstatic spiritual manifestations.

Montanus claimed to have received a series of direct revelations from the Spirit. As they went, "the Three," as they were called, spoke in ecstatic trance-like states and urged their followers to fast and pray, so that they might share these personal revelations. His preachings spread from his native Phrygia, where he reportedly proclaimed the village of Pepuza as the site of the New Jerusalem, across the contemporary Christian world, to Africa and Gaul. In Catharage they attracted the allegiance of Tertullian, who became the leader of a Montanist faction in that city that persisted until they were reconciled with the Church through the ministry of St. Augustine. The Montanists were generally recognized for their holiness and refused to compromise with Roman authorities on questions of honoring Roman state deities. As a result, they counted many martyrs among its numbers. Recent studies suggest that numerous Christian martrys, including the famous Saints Perpetua and Felicitas, who died in Carthage in the early second century, may have been Montanists or at least influenced by Montanism.

The movement was partly inspired by a reading of the Gospel of John— "I will send you the advocate [paraclete], the spirit of truth" (Heine 1987, 1989; Groh 1985). Together with an insistence on ascetic disciple and chastity, this doctrine of continuing revelation represented a challenge teaching authority of the bishops and split several Christian communities. Inscriptions from the region of Phryigia indicate that whole towns had become Montanist. The orthodox hierarchy thus fought to suppress it. Bishop Apollinarius found the church at Ancyra torn in two, and he opposed the "false prophesy" (quoted by Eusebius 5.16.5). Bishop St.Irenaeus of Lyon, who visited Rome during the height of the controversy, in the pontificate of Eleuterus, returned to find Lyon in dissension, and was inspired to write the first great statement of the mainstream Catholic position, Adversus Haereses. Euleuterus, for his part, seems to have approved of the Montanists at first but was later dissuaded from this view.

Tertullian claimed that only false accusations had moved him to condemn the movement:

- "For after the Bishop of Rome had acknowledged the prophetic gifts of Montanus, Prisca, and Maximilla, and, in consequence of the acknowledgment, had bestowed his peace on the churches of Asia and Phrygia, he (Praxeas), by importunately urging false accusations against the prophets themselves and their churches... compelled him to recall the pacific letter which he had issued, as well as to desist from his purpose of acknowledging the said gifts. By this Praxeas did a twofold service for the devil at Rome: he drove away prophecy, and he brought in heresy; he put to flight the Paraclete, and he crucified the Father." (Adversus Praxeam, I)

A native of Cathage, Tertullian was by far the best known defender of Montanists. He seems to have become a Montanist around the turn of third century, about 20 years or so after his conversion to Christianity. A respected intellectual champion of orthodoxy in every other respect, Tertulllian decried the spiritual laxity and corruption that he believed had infected the Catholic Church in his day. He believed that the new prophecy was genuinely motivated and saw it as a remedy to the Church's ills. His later writings grew increasinly caustic in decrying the moral corruption of what he now called "the church of a lot of bishops" (On Modesty). On questions of doctrine, however, he claimed that: "In this alone we differ, in that we do not receive the scond marriage (as Catholics allowed) and we do not refuse the prohecy of Montanus concerning the future judgment."

Local councils in Asia Minor reported moved against the Montanists as early as 177. When once such synod excommunicated Maximilla, she reportedly exclaimed "I am driven away like the wolf from the sheep. I am no wolf: I am word and spirit and power." Nevertheless the new prophecy retained significant pockets of influence in the region, as well as in North Africa and even Rome. Inscriptions in the Tembris valley of northern Phrygia, dated between 249 and 279, openly proclaim allegiance of towns to Montanism. Constantine the Great and other Emperors later passed laws against, and in by the time of Justian I, such legislations was stictly enforced. Still, small communities of Montanists reportedly persisted into the eighth century in some regions.

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Montanists

- Jerome's letter (xli) to Marcella to refute the heresy of Montanus, written in 385, "the passages brought together from the Gospel of John" having occasioned Marcella's questions

- EarlyChurch.org.uk Extensive bibliography and on-line articles.

Sources

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Historia ecclesiae, 5.16–18

Further reading

- Butler, Rex D., The New Prophecy & "New Visions": Evidence of Montanism in the Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas, Catholic University of America Press, 2006. ISBN: 0813214556

- Groh, Dennis E. 1985. "Utterance and exegesis: Biblical interpretation in the Montanist crisis," in Groh and Jewett, The Living Text (New York) pp 73 – 95.

- Heine, R.E., 1987 "The Role of the Gospel of John in the Montanist controversy," in Second Century v. 6, pp 1 – 18.

- Heine, R.E., 1989. "The Gospel of John and the Montanist debate at Rome," in Studia Patristica 21, pp 95 – 100.

- Pagels, Elaine, 2003. Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas ISBN 0375501568, contains a brief introduction to Montanism, with notes in chapter "God's Word or Human Words?"

- Trevett, Christine, 1996. Montanism: Gender, Authority and the New Prophecy. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN: 0521528704

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.