Malevich, Kazimir

Andy Wilhelm (talk | contribs) |

Andy Wilhelm (talk | contribs) m (Protected "Kazimir Malevich": Copyedited [edit=sysop:move=sysop]) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{Contracted}} |

{{epname|Malevich, Kazimir}} | {{epname|Malevich, Kazimir}} | ||

| − | '''Kazimir Severinovich Malevich''' ({{lang-ru|Казимир Северинович Малевич}}, {{lang-pl|Malewicz}}, [[Ukrainian language|Ukrainian]] transliteration Malevych | + | '''Kazimir Severinovich Malevich''' ({{lang-ru|Казимир Северинович Малевич}}, {{lang-pl|Malewicz}}, [[Ukrainian language|Ukrainian]] transliteration Malevych) (February 23, 1878 – May 15, 1935) was a painter and art theoretician, pioneer of geometric abstract art and one of the most important members of the [[Russian avant-garde]] as the founder of Suprematism. Suprematism, like [[Constructivism]] and [[Futurism]], among others, represented an explosion of new artistic movements in early twentieth-century [[Russia]], many of which spread quickly across [[Europe]]. This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, when ideas were in ferment and the old order was being swept away. Like many of his contemporaries, Malevich's movement fell victim to the emerging cultural orthodoxy of [[Socialist realism]] in the 1930s. The revolutionary movements were either silenced or driven underground. |

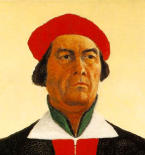

[[Image:Malevich-selfportrait-small.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Self-portrait, 1933 (detail)]] | [[Image:Malevich-selfportrait-small.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Self-portrait, 1933 (detail)]] | ||

==Life and work== | ==Life and work== | ||

| − | Kazimir Malevich was born near [[Kiev]], [[Ukraine]]. His parents, Seweryn and Ludwika Malewicz, were Polish | + | Kazimir Malevich was born near [[Kiev]], [[Ukraine]]. His parents, Seweryn and Ludwika Malewicz, were Polish [[Catholic]]s, and he was baptized in the [[Roman Catholic Church]]. His father was the manager of a sugar factory. Kazimir was the first of fourteen children, although only nine of the children survived into adulthood. His family moved often and he spent most of his childhood in the villages of Ukraine. He studied drawing in Kiev from 1895 to 1896. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | In 1904 he moved to [[Moscow]]. He studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture from 1904 to 1910. and in the studio of Fedor Rerberg in Moscow (1904–1910). In 1911 he participated in the second exhibition of the group ''Soyus Molod'ozhi'' (Union of Youth) in [[St. Petersburg]], together with [[Vladimir Tatlin]]. In 1912, the group held its third exhibition, including works by Aleksandra Ekster, Tatlin and others. In the same year he participated in exhibition of the collective ''Donkey's Tail'' in Moscow. In 1914 Malevich exhibited works in the ''Salon des Independants'' in Paris together with Alexander Archipenko, Sonia Delaunay, Aleksandra Ekster and Vadim Meller, among others. In 1915 he published his manifesto ''From Cubism to Suprematism''. | ||

==Suprematism== | ==Suprematism== | ||

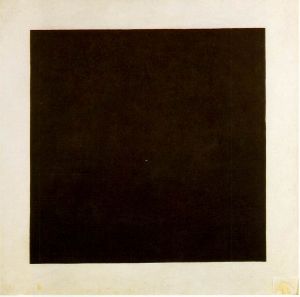

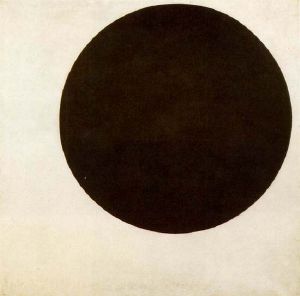

| − | [[Image:Malevich.black-square.jpg|right|thumb|''Black Square'' ([[Malevich]], 1913)]][[Image:black_circle.jpg|right|thumb|''Black Circle'' (Malevich]], 1913) | + | [[Image:Malevich.black-square.jpg|right|thumb|''Black Square'' ([[Malevich]], 1913)]][[Image:black_circle.jpg|right|thumb|''Black Circle'' (Malevich]], 1913)]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | After early experiments with various modernist styles including [[Cubism]] and [[Futurism (art)|Futurism]]—as exemplified by his [http://max.mmlc.northwestern.edu/~mdenner/Drama/plays/victory/1victory.html costume and set work] on the [[Cubo-Futurist]] opera ''Victory Over the Sun''—Malevich began working with abstract, non-objective geometric patterns, founding a movement he called Suprematism. Suprematism as an art movement focused on fundamental geometric forms (squares and circles) which formed in Russia in 1913. Famous examples of his Suprematist works include ''Black Square'' (1915) and ''White on White'' (1918). | ||

| − | When Malevich originated Suprematism in 1913 he was an established painter having exhibited in the ''Donkey's Tail'' and the ''Blaue Reiter'' exhibitions of 1912 with [[cubo-futurism|cubo-futurist]] works. The proliferation of new artistic forms in painting, poetry and theater as well as a revival of interest in the traditional folk art of Russia were a rich environment in which a [[Modernism|Modernist]] culture was being born. | + | When Malevich originated Suprematism in 1913 he was an established painter having exhibited in the ''Donkey's Tail'' and the ''Blaue Reiter'' exhibitions of 1912 with [[cubo-futurism|cubo-futurist]] works. The proliferation of new artistic forms in painting, [[poetry]] and theater as well as a revival of interest in the traditional folk art of Russia were a rich environment in which a [[Modernism|Modernist]] [[culture]] was being born. |

In his book ''The Non-Objective World'', Malevich described the inspiration which brought about the powerful image of the black square on a white ground: | In his book ''The Non-Objective World'', Malevich described the inspiration which brought about the powerful image of the black square on a white ground: | ||

| Line 25: | Line 23: | ||

:'I felt only night within me and it was then that I conceived the new art, which I called Suprematism'. | :'I felt only night within me and it was then that I conceived the new art, which I called Suprematism'. | ||

| − | Malevich also ascribed the birth of Suprematism to the ''Victory Over the Sun'', Aleksei Kruchenykh's [[Futurism|Futurist]] opera production for which he designed the sets and costumes in 1913. One of the drawings for the backcloth shows a black square divided diagonally into a black and a white triangle. Because of the simplicity of these basic forms they were able to signify a new beginning. | + | Malevich also ascribed the birth of Suprematism to the ''Victory Over the Sun'', Aleksei Kruchenykh's [[Futurism|Futurist]] opera production for which he designed the sets and costumes in 1913. One of the drawings for the backcloth shows a black square divided diagonally into a black and a white triangle. Because of the simplicity of these basic forms they were able to signify a new beginning. |

| − | He created a Suprematist 'grammar' based on fundamental geometric forms; the square and the circle. In the 0.10 Exhibition in 1915, Malevich exhibited his early experiments in Suprematist painting. The | + | He created a Suprematist 'grammar' based on fundamental geometric forms—the square and the circle. In the 0.10 Exhibition in 1915, Malevich exhibited his early experiments in Suprematist painting. The centerpiece of his show was the ''Black square on white'', placed in what is called the ''golden corner'' in ancient Russian Orthodox tradition; the place of the main icon in a house. |

| − | Another important influence on Malevich were the ideas of Russian mystic-mathematician [[P D Ouspensky]] who wrote of<p> 'a fourth dimension beyond the three to which our ordinary senses have access' | + | Another important influence on Malevich were the ideas of Russian mystic-mathematician [[P D Ouspensky]] who wrote of<p> 'a fourth dimension beyond the three to which our ordinary senses have access' (Gooding, 2001). |

[[Image:Malevici06.jpg|thumb|left|275px|1916 Suprematism (Supremus No. 58) Museum of Art, [[Krasnodar]]]] | [[Image:Malevici06.jpg|thumb|left|275px|1916 Suprematism (Supremus No. 58) Museum of Art, [[Krasnodar]]]] | ||

| Line 37: | Line 35: | ||

In 1915–1916 he worked with other Suprematist artists in a peasant/artisan co-operative in Skoptsi and Verbovka village. In 1916–1917 he participated in exhibitions of the ''Jack of Diamonds'' group in Moscow together with Nathan Altman, David Burliuk and A. Ekster, among others. | In 1915–1916 he worked with other Suprematist artists in a peasant/artisan co-operative in Skoptsi and Verbovka village. In 1916–1917 he participated in exhibitions of the ''Jack of Diamonds'' group in Moscow together with Nathan Altman, David Burliuk and A. Ekster, among others. | ||

| − | The Supremus group which, in addition to Malevich included Aleksandra Ekster, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Ivan Kliun, Liubov Popova, Nina Genke-Meller, Ivan Puni and Ksenia Boguslavskaya met from 1915 onwards to discuss the philosophy of Suprematism and its development into other areas of intellectual life. | + | The Supremus group which, in addition to Malevich included Aleksandra Ekster, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Ivan Kliun, Liubov Popova, Nina Genke-Meller, Ivan Puni and Ksenia Boguslavskaya met from 1915 onwards to discuss the philosophy of Suprematism and its development into other areas of intellectual life. |

This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, when ideas were in ferment and the old order was being swept away. By 1920 the state was becoming [[authoritarianism|authoritarian]] and limiting the freedom of artists. From 1918 the [[Russian avant-garde]] experienced the limiting of their artistic freedoms by the authorities and in 1934 the doctrine of [[Socialist Realism]] became official policy, and prohibited abstraction and divergence of artistic expression. Malevich nevertheless retained his main conception. In his self-portrait of 1933 he represented himself in a traditional way—the only way permitted by [[Stalinist]] cultural policy—but signed the picture with a tiny black-over-white square. | This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, when ideas were in ferment and the old order was being swept away. By 1920 the state was becoming [[authoritarianism|authoritarian]] and limiting the freedom of artists. From 1918 the [[Russian avant-garde]] experienced the limiting of their artistic freedoms by the authorities and in 1934 the doctrine of [[Socialist Realism]] became official policy, and prohibited abstraction and divergence of artistic expression. Malevich nevertheless retained his main conception. In his self-portrait of 1933 he represented himself in a traditional way—the only way permitted by [[Stalinist]] cultural policy—but signed the picture with a tiny black-over-white square. | ||

| Line 43: | Line 41: | ||

==Other interests== | ==Other interests== | ||

| − | Malevich also acknowledged that his fascination with aerial photography and aviation led him to [[abstract art|abstract]]ions inspired by or derived from aerial landscapes. Harvard doctoral candidate | + | Malevich also acknowledged that his fascination with aerial [[photography]] and [[aviation]] led him to [[abstract art|abstract]]ions inspired by or derived from aerial landscapes. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: “In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception .... In a series of diagrams illustrating the ‘environments' that influence various painterly styles, the Suprematist is associated with a series of aerial views rendering the familiar [[landscape]] into an abstraction..." |

[[Image:Malevich.black-square.jpg|thumb|right|Black Square, 1915, Oil on Canvas, [[State Russian Museum]], St.Petersburg]] | [[Image:Malevich.black-square.jpg|thumb|right|Black Square, 1915, Oil on Canvas, [[State Russian Museum]], St.Petersburg]] | ||

| − | Malevich was a member of the Collegium on the Arts of Narkompros, the commission for the protection of monuments and the museums commission (all from 1918–1919). He taught at the Vitebsk Practical Art School in Russia (now part of [[Belarus]]) (1919–1922), the Leningrad Academy of Arts (1922–1927), the Kiev State Art Institute (1927–1929), and the House of the Arts in Leningrad (1930). He wrote the book '’'The World as Non-Objectivity’'' (Munich 1926; English trans. 1976) which outlines his Suprematist theories. | + | Malevich was a member of the Collegium on the Arts of Narkompros, the commission for the protection of monuments and the museums commission (all from 1918–1919). He taught at the Vitebsk Practical Art School in Russia (now part of [[Belarus]]) (1919–1922), the Leningrad Academy of Arts (1922–1927), the Kiev State Art Institute (1927–1929), and the House of the Arts in Leningrad (1930). He wrote the book '’'The World as Non-Objectivity’'' (Munich 1926; English trans. 1976) '' which outlines his Suprematist theories. |

In 1927, he traveled to Warsaw and then to Germany for a retrospective that brought him international fame, and arranged to leave most of the paintings behind when he returned to the Soviet Union. When the [[Stalinism|Stalinist]] regime turned against [[Modernism|modernist]] "[[Bourgeoisie|bourgeois]]" art, Malevich was persecuted. Many of his works were confiscated or destroyed, and he died in poverty and obscurity in Leningrad, [[Soviet Union]] (today Saint Petersburg, [[Russia]]). | In 1927, he traveled to Warsaw and then to Germany for a retrospective that brought him international fame, and arranged to leave most of the paintings behind when he returned to the Soviet Union. When the [[Stalinism|Stalinist]] regime turned against [[Modernism|modernist]] "[[Bourgeoisie|bourgeois]]" art, Malevich was persecuted. Many of his works were confiscated or destroyed, and he died in poverty and obscurity in Leningrad, [[Soviet Union]] (today Saint Petersburg, [[Russia]]). | ||

| Line 86: | Line 84: | ||

* 1928-32 Complex Presentiment: Half-Figure in a Yellow Shirt | * 1928-32 Complex Presentiment: Half-Figure in a Yellow Shirt | ||

* 1932-34 Running Man | * 1932-34 Running Man | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Dreikausen, Margret. [http://www.worldcatlibraries.org/wcpa/ow/d729543b2ed70922.html "Aerial Perception: The Earth as Seen from Aircraft and Spacecraft and Its Influence on Contemporary Art"] Associated University Presses: Cranbury, NJ; [[London]], [[England]]; Mississauga, Ontario: 1985. Retrieved December 23, 2007. | |

| − | + | * Gooding, Mel. ''Abstract Art''. Tate Publishing, 2001. ISBN 9781854373021 | |

| − | * Dreikausen, Margret | + | * Gray, Camilla. ''The Russian Experiment in Art''. Thames and Hudson, 1976. ISBN 9780500202074 |

| − | * | + | * Gurianova, Nina. ''Kazimir Malevich and Suprematism 1878-1935''. Gilles Néret, Taschen, 2003. ISBN 9780892072651 |

| − | * | + | * Malevich, Kasimir, trans. ''The Non-objective World''. Howard Dearstyne, Paul Theobald, 1959. ISBN 9780486429748 |

| + | == External links == | ||

| + | {{commonscat|Kazimir Malevich}} | ||

| + | * [http://www.guggenheimcollection.org/site/artist_bio_94.html "Kazimir Malevich"] ''Guggenheim Museum''. Retrieved December 23, 2007. | ||

| + | * [http://www.artchive.com/artchive/M/malevich/b_square.jpg.html "Black Square"] ''The Artchive''. Retrieved December 23, 2007. | ||

| + | * [http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/art/20_ptg.html "White on White"] ''Museum of Modern Art''. Retrieved December 23, 2007. | ||

| + | * [http://www.potemkinpress.com/english/pubs/malewitsch.htm "Kazimir Malevich: The White Rectangle. Writings on Film"] ''Potemkin Press online''. Retrieved December 23, 2007. | ||

| + | * [http://www.malevich.de DADA Collection] ''Malevich Gallerie''. Retrieved December 23, 2007. | ||

| + | * Isobel Hunter, [http://www.ce-review.org/99/3/ondisplay3_hunter.html "Zaum and Sun: The 'first Futurist opera' revisited "] ''Central Europe Review''. Retrieved December 23, 2007. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Westernart}} | {{Westernart}} | ||

| − | + | [[Category:biography]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Artists]] | [[Category:Artists]] | ||

{{credit|96044982}} | {{credit|96044982}} | ||

Revision as of 19:40, 23 December 2007

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich (Russian: Казимир Северинович Малевич, Polish: Malewicz, Ukrainian transliteration Malevych) (February 23, 1878 – May 15, 1935) was a painter and art theoretician, pioneer of geometric abstract art and one of the most important members of the Russian avant-garde as the founder of Suprematism. Suprematism, like Constructivism and Futurism, among others, represented an explosion of new artistic movements in early twentieth-century Russia, many of which spread quickly across Europe. This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, when ideas were in ferment and the old order was being swept away. Like many of his contemporaries, Malevich's movement fell victim to the emerging cultural orthodoxy of Socialist realism in the 1930s. The revolutionary movements were either silenced or driven underground.

Life and work

Kazimir Malevich was born near Kiev, Ukraine. His parents, Seweryn and Ludwika Malewicz, were Polish Catholics, and he was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church. His father was the manager of a sugar factory. Kazimir was the first of fourteen children, although only nine of the children survived into adulthood. His family moved often and he spent most of his childhood in the villages of Ukraine. He studied drawing in Kiev from 1895 to 1896.

In 1904 he moved to Moscow. He studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture from 1904 to 1910. and in the studio of Fedor Rerberg in Moscow (1904–1910). In 1911 he participated in the second exhibition of the group Soyus Molod'ozhi (Union of Youth) in St. Petersburg, together with Vladimir Tatlin. In 1912, the group held its third exhibition, including works by Aleksandra Ekster, Tatlin and others. In the same year he participated in exhibition of the collective Donkey's Tail in Moscow. In 1914 Malevich exhibited works in the Salon des Independants in Paris together with Alexander Archipenko, Sonia Delaunay, Aleksandra Ekster and Vadim Meller, among others. In 1915 he published his manifesto From Cubism to Suprematism.

Suprematism

, 1913)]]

After early experiments with various modernist styles including Cubism and Futurism—as exemplified by his costume and set work on the Cubo-Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun—Malevich began working with abstract, non-objective geometric patterns, founding a movement he called Suprematism. Suprematism as an art movement focused on fundamental geometric forms (squares and circles) which formed in Russia in 1913. Famous examples of his Suprematist works include Black Square (1915) and White on White (1918).

When Malevich originated Suprematism in 1913 he was an established painter having exhibited in the Donkey's Tail and the Blaue Reiter exhibitions of 1912 with cubo-futurist works. The proliferation of new artistic forms in painting, poetry and theater as well as a revival of interest in the traditional folk art of Russia were a rich environment in which a Modernist culture was being born.

In his book The Non-Objective World, Malevich described the inspiration which brought about the powerful image of the black square on a white ground:

- 'I felt only night within me and it was then that I conceived the new art, which I called Suprematism'.

Malevich also ascribed the birth of Suprematism to the Victory Over the Sun, Aleksei Kruchenykh's Futurist opera production for which he designed the sets and costumes in 1913. One of the drawings for the backcloth shows a black square divided diagonally into a black and a white triangle. Because of the simplicity of these basic forms they were able to signify a new beginning.

He created a Suprematist 'grammar' based on fundamental geometric forms—the square and the circle. In the 0.10 Exhibition in 1915, Malevich exhibited his early experiments in Suprematist painting. The centerpiece of his show was the Black square on white, placed in what is called the golden corner in ancient Russian Orthodox tradition; the place of the main icon in a house.

Another important influence on Malevich were the ideas of Russian mystic-mathematician P D Ouspensky who wrote of

'a fourth dimension beyond the three to which our ordinary senses have access' (Gooding, 2001).

Some of the titles to paintings in 1915 express the concept of a non-euclidian geometry which imagined forms in movement, or through time; titles such as: Two dimensional painted masses in the state of movement. These give some indications towards an understanding of the Suprematic compositions produced between 1915 and 1918.

In 1915–1916 he worked with other Suprematist artists in a peasant/artisan co-operative in Skoptsi and Verbovka village. In 1916–1917 he participated in exhibitions of the Jack of Diamonds group in Moscow together with Nathan Altman, David Burliuk and A. Ekster, among others.

The Supremus group which, in addition to Malevich included Aleksandra Ekster, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Ivan Kliun, Liubov Popova, Nina Genke-Meller, Ivan Puni and Ksenia Boguslavskaya met from 1915 onwards to discuss the philosophy of Suprematism and its development into other areas of intellectual life.

This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, when ideas were in ferment and the old order was being swept away. By 1920 the state was becoming authoritarian and limiting the freedom of artists. From 1918 the Russian avant-garde experienced the limiting of their artistic freedoms by the authorities and in 1934 the doctrine of Socialist Realism became official policy, and prohibited abstraction and divergence of artistic expression. Malevich nevertheless retained his main conception. In his self-portrait of 1933 he represented himself in a traditional way—the only way permitted by Stalinist cultural policy—but signed the picture with a tiny black-over-white square.

Other interests

Malevich also acknowledged that his fascination with aerial photography and aviation led him to abstractions inspired by or derived from aerial landscapes. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: “In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception .... In a series of diagrams illustrating the ‘environments' that influence various painterly styles, the Suprematist is associated with a series of aerial views rendering the familiar landscape into an abstraction..."

Malevich was a member of the Collegium on the Arts of Narkompros, the commission for the protection of monuments and the museums commission (all from 1918–1919). He taught at the Vitebsk Practical Art School in Russia (now part of Belarus) (1919–1922), the Leningrad Academy of Arts (1922–1927), the Kiev State Art Institute (1927–1929), and the House of the Arts in Leningrad (1930). He wrote the book '’'The World as Non-Objectivity’ (Munich 1926; English trans. 1976) which outlines his Suprematist theories.

In 1927, he traveled to Warsaw and then to Germany for a retrospective that brought him international fame, and arranged to leave most of the paintings behind when he returned to the Soviet Union. When the Stalinist regime turned against modernist "bourgeois" art, Malevich was persecuted. Many of his works were confiscated or destroyed, and he died in poverty and obscurity in Leningrad, Soviet Union (today Saint Petersburg, Russia).

Trivia

The possible smuggling of surviving Malevich paintings out of Russia is a key to the plot line of Martin Cruz Smith's thriller "Red Square."

Selected works

- 1912 Morning in the Country after Snowstorm

- 1912 The Woodcutter

- 1912-13 Reaper on Red Background

- 1914 The Aviator

- 1914 An Englishman in Moscow

- 1914 Soldier of the First Division

- 1915 Black Square and Red Square

- 1915 Red Square: Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions

- 1915 Suprematist Composition

- 1915 Suprematism (1915)

- 1915 Suprematist Painting: Aeroplane Flying

- 1915 Suprematism: Self-Portrait in Two Dimensions

- 1915-16 Suprematist Painting (Ludwigshafen)

- 1916 Suprematist Painting (1916)

- 1916 Supremus No. 56

- 1916-17 Suprematism (1916-17)

- 1917 Suprematist Painting (1917)

- 1928-32 Complex Presentiment: Half-Figure in a Yellow Shirt

- 1932-34 Running Man

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dreikausen, Margret. "Aerial Perception: The Earth as Seen from Aircraft and Spacecraft and Its Influence on Contemporary Art" Associated University Presses: Cranbury, NJ; London, England; Mississauga, Ontario: 1985. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- Gooding, Mel. Abstract Art. Tate Publishing, 2001. ISBN 9781854373021

- Gray, Camilla. The Russian Experiment in Art. Thames and Hudson, 1976. ISBN 9780500202074

- Gurianova, Nina. Kazimir Malevich and Suprematism 1878-1935. Gilles Néret, Taschen, 2003. ISBN 9780892072651

- Malevich, Kasimir, trans. The Non-objective World. Howard Dearstyne, Paul Theobald, 1959. ISBN 9780486429748

External links

- "Kazimir Malevich" Guggenheim Museum. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- "Black Square" The Artchive. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- "White on White" Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- "Kazimir Malevich: The White Rectangle. Writings on Film" Potemkin Press online. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- DADA Collection Malevich Gallerie. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- Isobel Hunter, "Zaum and Sun: The 'first Futurist opera' revisited " Central Europe Review. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

| Western art movements |

| Renaissance · Mannerism · Baroque · Rococo · Neoclassicism · Romanticism · Realism · Pre-Raphaelite · Academic · Impressionism · Post-Impressionism |

| 20th century |

| Modernism · Cubism · Expressionism · Abstract expressionism · Abstract · Neue Künstlervereinigung München · Der Blaue Reiter · Die Brücke · Dada · Fauvism · Art Nouveau · Bauhaus · De Stijl · Art Deco · Pop art · Futurism · Suprematism · Surrealism · Minimalism · Post-Modernism · Conceptual art |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.