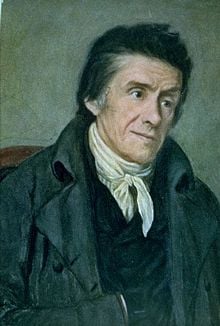

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (born January 12, 1746 in Zurich, Switzerland; died February 17, 1827 in Brugg) was a Swiss pedagogue and educational reformer, who influenced development of education system in many European countries and America.

Life

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi was born in Zurich, Switzerland on January 12, 1746. His father died when Johann was only five, and his mother brought up both him and his sister. Johann started school rather late, at the age of nine, but successfully completed everything in time. He initially enrolled to study ministry at the University of Zurich, but due to his shyness he decided to switch his major from theology into law.

At the University of Zurich, Pestalozzi met Johann Kasper Lavater and the reform party. He entered the world of politics. However, the death of his friend Johann Kasper Bluntschli turned him from politics, and induced him to devote himself to education.

Through his association with reformists, Pestalozzi had become aware of social problems which helped him develop a deeper sense for human suffering. He began to research different ideas and schemes for improving the condition of the people. Influenced by the ideas of Rousseau to "go back to nature," Pestalozzi started a social experiment—he purchased a piece of waste land at Neuhof in Aargau, where he attempted to cultivate madder, a plant the roots of which are the source of a red dye. His idea was to use this farm to provide shelter and education for orphans.

Pestalozzi married his childhood friend and they had his first child, Jacobi, soon after. He developed his teaching methods from teaching Jacobi based on Rousseau's ideas in Emile. His wife proved to be a “down-to-earth” woman, who helped her husband curb many of his impractical ideas. His social experiment with a group of orphans was successful for five whole years. Nevertheless, the project failed financially and the family went bankrupt in 1780. However, when everything looked dark and over, Pestalozzi’s project was saved by Elizabeth Naef, a neighbor, who fortunately turned the whole farm project into a successful business.

In 1780, Pestalozzi wrote a series of reflections The Evening Hours of a Hermit, which outlined his basic theory that education begins at home and should occur naturally through direct experience. This was followed by his masterpiece, Leonard and Gertrude (1781), an account of the gradual reformation, first of a household, and then of a whole village, by the efforts of a good and devoted woman. This work became a bestseller in Germany, and the name of Pestalozzi became internationally famous.

The French invasion of Switzerland in 1798 brought into view Pestalozzi’s truly heroic character. A number of children were left in Stans, in Canton Unterwalden, on the shores of Lake Lucerne, without parents, home, food, or shelter. Pestalozzi gathered a number of them in a deserted convent which he turned into an orphanage. During the winter he personally tended them with the utmost devotion, but in June 1799 the building was reclaimed by the French for use as a hospital, and the orphanage was closed.

In 1799, Pestalozzi started yet another project. He volunteered his service as a teacher to the village of Burgdorf, where he used his own educational methods in his work with children. However, due to the non-traditional nature of his teaching, the villagers became suspicious of Pestalozzi’s success, with the result that he was compelled to open his own private school. In a short time, with two additional teachers the school became the center of international attention and fame, and received government support.

In 1801, Pestalozzi gave an exposition of his ideas on education in the book How Gertrude teaches her Children. In 1802, he went as deputy to Paris, and tried unsucessfully to interest Napoleon I of France in a scheme of national education.

In 1805, Pestalozzi moved his school to a castle at Yverdon, near Neuchâtel, and for twenty years he worked steadily on this project. It became world famous, and he was visited by all who took an interest in education, including Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, Count Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias, and Anne Louise Germaine de Staël. He was praised by Wilhelm von Humboldt and by Johann Gottlieb Fichte. Many visiting educators studied his methods and incorporated them into their own teaching, including Carl Ritter and Friedrich Fröbel. Educational systems in countries all over Europe were modified to reflect Pestalozzi’s ideas.

As the Yverdon school grew in size, it lost its family spirit as some of the teachers changed Pestalozzi’s original ideas, resulting in numerous quarrels and conflicts. After the school closed in 1826, at the age of eighty Pestalozzi retired to his Neuhof farm. There he wrote his last work, the Swan Song. He died soon after, on February 17, 1827.

Work

Pestalozzi’s principles of education are predominantly expressed in his seminal work How Gertrude teaches her Children. In it he argues that children should learn through experience – through physical activity and through things. His ideas can be summarized in following way:

1) Goal of Education The goal of education is not to discover, but to unfold the natural faculties latent and hidden in every human being. In another words, educators need to focus on human being, a child, and not on education per se. There are two general goals of education – education for the individual and education for the social. On the individual level, education needs to focus on intellectual, moral, social, and emotional development of a human being. On the social level, education provides the means for general development of the whole society. In another words, the more educated the individual parts of the society, the more educated and developed the whole society. For Pestalozzi thus education plays central role in the improvement of society.

2) Method of Education Education should be centered on a child, not the curriculum. Since knowledge lies within human beings, teachers’ purpose is to find the way to unfold that hidden knowledge. Pestalozzi suggests direct experience being the best method. The teacher should not teach through words, but through the nature. Nothing is better than a direct sensory experience. In addition, Pestalozzi thought that in the early education, children should use no books, but rather learn through direct experience. Child needs first to learn to observe, to correct its own mistakes, and to analyze and describe the object of its inquiry. Only after that child can start to use books. This is inductive method in education – starting from simple objects and simple observation, and building on it toward more complex and abstract things. For the reason for children to get more experience from the nature, Pestalozzi expanded the elementary school curriculum, including geography, natural science, fine art and music. He advocated spontaneity and self-activity, in contrast to teacher-centered rigid curriculum-based method used in other schools.

3) Discipline in the classroom Pestalozzi started with the idea that classroom needs to be like family. The atmosphere in it must be loving and caring, like in a typical Christian family. Starting from that assumption, Pestalozzi suggested that teachers always need to keep in mind to be loving and kind, as they want all the children in the classroom to be. Harsh discipline, as mostly used in schools in that time, only alienates children from the teachers, and thus prevents normal, natural development of children. The idea of the “family classroom” Pestalozzi got from the way his mother educated him and his sister. Pestalozzi said, “ There can be no doubt that within the living room of every household are united the basic elements of all true human education in its whole range”. Family is thus, for Pestalozzi, an important part of education in general.

Legacy

In essence, Pestalozzi used Rousseau’s ideas, adopted them and implemented in a more practical way. Unlike other philosophers, however, who only theorized about education, Pestalozzi put his ideas into practice. His projects at Neuhof and Yverdon became so effective that they laid foundation for what will once be named the “Pestalozzi Method”.

As Pestalozzi once said himself, the real work of his life did not lie in Burgdorf or Yverdon. It lays in the principles of education which he practiced, the development of his observation, the training of the whole man, the sympathetic application of the teacher to the taught, of which he left an example in his six months labors at Stans. He had the deepest effect on all branches of education, and his influence is far from being exhausted. He inspired not only elementary school educators in Prussia and some other European countries, but also had impact on American education. Dr. Edward A. Sheldon, the superintendent of schools in Oswego, New York, imported some material based on Pestalozzi’s teaching, and started to implement it in his school. After the initial success, more teachers started to be educated in Pestalozzi’s method. The Normal School at Oswego became the center of Pestalozzi education in the United States. Soon after that other schools all across the nation adopted this method into their curriculums, and the changes took roots for good. The teaching of Pestalozzi became the building block of the whole American school system.

Pestalozzi's complete works were published at Stuttgart in 1819, 1826, and an edition by Seyffarth appeared at Berlin in 1881.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates text from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, a publication in the public domain.

- Silber, K. (1973). Pestalozzi: The man and his work (3nd edition). London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0710021186

External Links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.